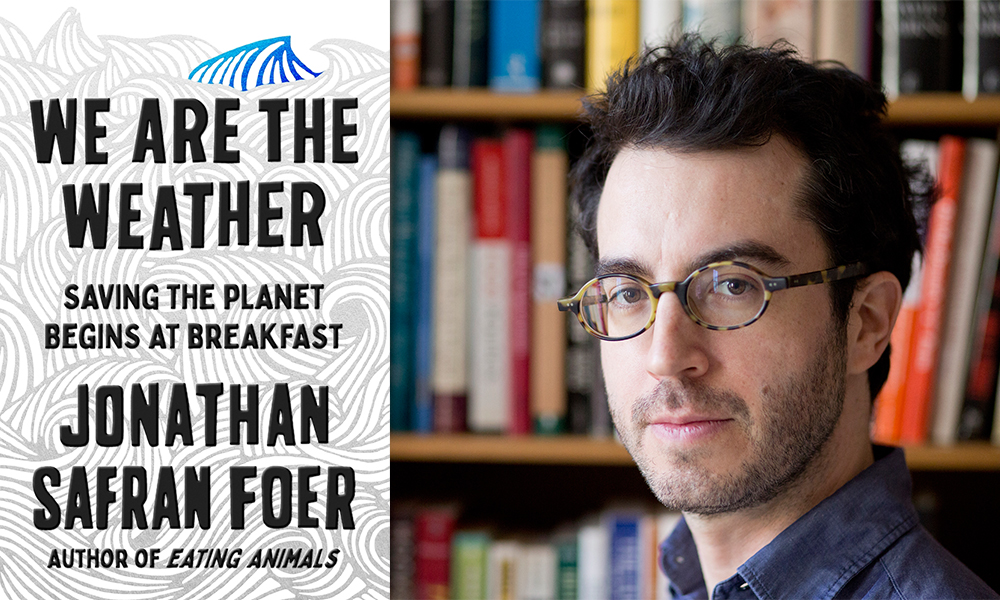

How much do we need to change our own individual diets to help slow down climate change? How much should we focus on “reaching our destination,” not “perfecting our process” along the way? When I want to ask such questions, I pose them to Jonathan Safran Foer. This present conversation focuses on Foer’s book We Are the Weather: Saving the Planet Begins at Breakfast. Foer is the author of the novels Everything is Illuminated, Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close, and Here I Am, and the nonfiction book Eating Animals. His work has received numerous awards and has been translated into 36 languages. He lives in Brooklyn.

¤

ANDY FITCH: In what ways does We Are the Weather maybe not exist without Eating Animals? And how might We Are the Weather revisit, retell, reshape, revise parts of that predecessor?

JONATHAN SAFRAN FOER: Animal agriculture is a subject I’ve given a lot of thought to for years, and a kind of concentrated attention to when writing Eating Animals. Eating Animals touches on the environmental implications of factory farming, but that book came from a different type of thrust or incentive. It focuses more on the open discomfort I’ve had with meat since I was a kid. Frankly, most people I’ve spoken to about this discomfort share it in some way — which doesn’t necessarily indicate some wrongness or problem, but which I do find interesting. Very, very few of us in my experience (which at this point includes conversations with thousands of people, most of whom eat meat) feel no degree of discomfort, or completely fail to recognize the stakes when one eats meat: in terms of animal welfare, in terms of more indirect issues like world hunger or the treatment of farmers.

So Eating Animals offers a kind of holistic examination of meat, but leans heavily on my own feelings and my family’s history and future. But for We Are the Weather, I wanted to write about climate change. You cannot offer anything like a full story about climate change today without including animal agriculture. Though here the connection to Eating Animals does get a bit awkward, because I didn’t want the new book to come across as a case against meat-eating. I wanted to present both a personal account and a broader questioning of what we can do as people who aren’t legislators, who don’t have much power outside of our individual choices to act on what we all care about. And when I refer to “what we all care about,” I mean as we reach this new cultural moment in which we no longer have a significant number of Americans denying that human activity is causing the planet to warm. Twice as many Americans believe in the existence of Bigfoot as deny the fact of human-caused climate change.

I did an interview with Ben Shapiro the other day. Some audiences might hold up Ben Shapiro as exactly the kind of problematic person to avoid joining in a discussion about global warming. But he defined climate change as the increase of between two and six degrees centigrade that will occur over the next century, caused by human activities — which I consider a thorough, solid description. So I wanted to write a book starting from the fact that almost everybody knows what needs to be done, and yet almost nobody is doing what needs to be done. This book really began with me hearing myself say: “We need to do something. They need to do something. Somebody has to do something.” I would attend the marches and affix the bumper stickers and wear the T-shirts and all of that. But I did practically nothing. If you look at my life compared to the life of the average climate-change denier, I’m probably much worse. So I wanted to write a book about that. And when writing this book, it became immediately clear that meat would be the centerpiece.

Sure, and I’ll leave it to Terry Gross to ask about We Are the Weather’s confessional scenes of you, in a logistical crunch and / or personal panic, inhaling a factory-farmed burger. But during my own vegan years, I never much craved a bite of beef. I just often felt a bit delirious, and occasionally socially difficult, when I didn’t have animal products in my repertoire. So could you here make concrete your craving for meat? Could you use something like narrative texture to make palpable the pull (emotional, physiological, interpersonal, intergenerational, cultural) of the foodways that this book seeks to push (however modestly) beyond? Let’s say that a stressed, hungry would-be vegan walks into an airport bar. What happens next?

I actually just had this 10 minutes ago. I just went to this neighborhood place called Cafe Madeline in Brooklyn. As I perused the menu, I spotted a dozen things I wanted to eat but that I’ve also decided I don’t want to eat. Striking the right balance is still quite tricky.

Sometimes people eat meat because they ate it yesterday. They might have enjoyed it or might not have. It doesn’t mean much to them in any kind of psychological way. It’s just what’s there. Or sometimes we eat meat because we do crave it physically, along the lines of: “You know I really could go for a burger right now.” Sometimes a smell or a sight inspires that craving. The person sitting across from me will order a chicken parm or a steak or whatever. And I’ll think: Oh man, that looks really good.

Still I don’t want to overstate this desire. Many, many things in life look good. Yet we don’t pursue them, because we’re adults. We might not have much experience with declining to pursue certain foods. But we have tons of experience with not pursuing certain interpersonal desires, whether through anger or through attraction. We know that the desire to do or to possess something isn’t the justification for doing it or taking it. It would be nice to just walk out of a store without paying for things. But we’ve grown so used to ignoring this desire that we don’t even feel ourselves ignore it — or maybe to some extent stopped having it.

But so for whatever reason (and maybe the reasons are totally obvious), the more I thought about this subject, the more I actually wanted to eat meat. I guess because it had become even more of a taboo. I don’t exactly know. I wish that desire would just disappear, but it hasn’t disappeared. And I bring that desire into this book because it’s real, and also because I consider it helpful to be honest about one’s own struggles. Right now, it feels to me that our discussions about climate change (or about any political topic) go immediately to righteous extremes and accusations and defensiveness, to measuring the failings or ignorance of the person supposedly on the other end of this conversation. That has only made worse our tendency to frame climate change as this politicized issue, to act as if liberals care about the planet more than conservatives do — which I don’t believe. Talking to Ben Shapiro helped me realize that certain approaches to this conversation wouldn’t work for him, but that our conversation still could reach the same reasonable outcome.

Yeah a decent number of Bush 43 officials have told me recently that someone else (not them) in the administration had denied climate-change realities, a political stance which these particular officials had always considered just plain wrong. It does feel like an interesting moment to talk to established conservatives about climate change — and also to place our own dissociative habits next to theirs, rather than celebrating our supposed moral purity. And so in terms of We Are the Weather’s own rhetorical strategies: if forcing people to change their intimately held beliefs often proves impossible, if speaking to audiences’ identity-shaping core requires asking some uncomfortable questions of oneself, if behavioral nudges shape us much more than we might notice or care to admit, how might encountering this book’s heterogeneous array of autobiographical scenes and introspective musings and prescriptive scaffolds and proscriptive cautionary tales (making me think of some cross among Marcus Aurelius’s Meditations and Frank O’Hara’s “Meditations in an Emergency” and your own personalized form of meditations on apathy) model for readers what it’s like to navigate one’s way amid the “neo-liberal myth that individual decisions have ultimate power,” and the “defeatist myth that individual decisions have no power at all”?

I guess I’ll have to give you a heterogeneous answer. First, when I write, I also become (as I assume most authors do) the reader. I think of every author trying to write something that he or she hasn’t read before and wants to read — something moving or persuasive or informative or provocative, whatever one’s particular bullseye might be. But I think we make a bad mistake when we try to anticipate another reader’s bullseye. In a certain way, literature is the antidote to this mistake. And here I’d sensed my own weird reactions to both fiction and nonfiction climate-change literature. I know very well the experience of starting a book and thinking: Oh my god, everybody has to read this. And then 15 pages later I’m like: What’s for lunch? How can I get out of this? When will the boredom stop? And I also know well the experience of feeling moved in this highly intellectualized and probably narcissistic way by a book, but without it activating any real change in my life.

Again, I’ve probably read more about the environment and climate change than many people who have done much more to actually change their behavior and address climate change. So I did feel the need to admit to that embarrassing and intolerable reality. But I also wanted to use those autobiographical elements to think through what might move me as a reader. Like how the hell can I kick my ass into action? The book’s dialogue section, for example, isn’t just performative. That really was me arguing with myself, calling myself out, questioning if I could or should forgive myself. Obviously, it’s not a real-time record of an actual internal debate. But it might be closer than you think. Or when this “Dispute with the Soul” section questions whether the earlier fact-heavy “How to Prevent the Greatest Dying” section worked, again that does reflect my lived experience of reading the book while I wrote it.

Now, all that said, I obviously did know I’d be publishing this book. It’s not a diary for keeping in my desk drawer. I did give thought to other readers’ experiences, especially with Eating Animals in the background — wondering what might push people away or invite people in. And I have found that many, like me, feel invited in when somebody shares their thought process more than their conclusions. And I’ll feel even more welcome when this thought process includes personal and intellectual contradictions and struggles — all as part of a process that never stops changing.

So to start progressing through We Are the Weather’s various parts: your book’s opening “Unbelievable” section quickly arrives at a vision of inhaling human / interspecies breaths from across civilizational history, all building towards the assertion: “That I had a place in all of that — that I could not escape my place in all of that — was what I found most astonishing.” And here, following up on your astrobiological book title, I wonder what it might mean to consider our present Anthropocenic position from the perspective of the astonished person (with astonishment of course at times including painfully raw recognitions of our own odious complicities). Or if we admit our present failings to “summon and sustain the necessary emotions” to address climate challenges, how might we start to reconceive the constraints we face today (“We do not have the luxury of living in our time.… In a way that was not true for our ancestors, the lives we live will create a future that cannot be undone”) in the most proactive and positive sense? How might a more astonished point of view help us see this era as, in FDR-esque terms, calling less for a sacrifice of our most fundamental desires, and more for the emergence of our most tenaciously high-minded selves?

I don’t know if I can give a better answer than that question you just asked. The book gives the analogy of the overview effect that astronauts feel when looking back at the Earth and facing this sudden recognition that we actually live on a planet. Or maybe sunrise and sunset can give us all a somewhat abstract sense of this same feeling, and maybe even a reminder of our planet’s fragility. I do think of astonishment as an important part of the process. And for me at least, astonishment and wonder tend to come from thinking about interconnectedness and scale.

So, for example, I just learned the other day roughly how many generations there have been of recorded human history: 250. That’s just mind-blowing, right? I mean, at one point, four generations lived in my parents’ house, and four generations is not a tiny fraction of 250. Once you can sort of indulge that fact, that sense of scale for the entirety of our human history, how can you not feel astonished? This was true when I was a kid and it’s probably even more true now, with reminders of…did you ever see Powers of 10?

Yeah sure, the Eames brothers.

For a kid, that was fucking inspiring: those felt reminders of our bigness, our smallness, our fastness, our slowness, our ability to create, to destroy — and also our meaninglessness and our meaningfulness. Religion does a good job with this. I’m not a religious person, but I admire how religion can give us occasions to remember scale, or even just how a cathedral’s architecture can make your eyes and thoughts literally rise, or how religious practice requires setting aside time to reflect on the passage of time itself, how it creates context for acknowledging important moments in a week or in a life. As 21st-century Americans, we probably have far fewer of these occasions than our ancestors did. We have oriented ourselves toward modes of activity and communication that actively discourage this kind of wonder, that instead emphasize expediency as the highest value. So when these moments of perspective hit, for me in any case, they really create not just a kind of flash-in-the-pan feeling, but a recovered sense of responsibility and a desire to be careful.

In Eating Animals, I explicitly acknowledge deciding to write that book when my wife became pregnant. That experience offered a quintessential moment of the overview effect — a recognition that I wasn’t the beginning, and wouldn’t be the end. There’s a smallness in that, but also a hugeness in having to make decisions on this vulnerable new person’s behalf, in needing to take care. For me, that all meant taking this (never very pressing, urgent, or consistent) feeling I’d had for more than two decades, and finally devoting a couple years to really digging into both what the world is like and what I am like. So then the problem became: how can you sustain that kind of wonder?

It’s not that hard actually to make somebody feel moved. Mark Twain once said that quitting smoking was the easiest thing in the world, and that he had done it dozens of times. Similarly, it’s pretty easy to persuade someone to become vegetarian for a day. It’s pretty easy in the moment to persuade someone to give up air travel. But how do you persuade somebody to continue these behaviors once the moment of inspiration has passed? I think that has a lot to do with keeping a conversation alive inside yourself.

So just to return to your question about craving meat: at that cafe this morning, as I looked over the menu, I did have to make the effort to say: “Stop for a second. What do you want? What else do you want? How can you weigh those wants?” They’re not the most amazing internal debates or personal choices, but the accumulation of these kinds of conversations with myself and decisions that I make do matter to me. And as other people have their own equivalent conversations with themselves, and make their own decisions, this accumulation does matter to the world itself. There is nothing in our lives that doesn’t come from that.

You also mentioned “indulging” in facts. And following the “Unbelievable” section’s evocations of astonishment, we get the understatedly aphoristic, bullet-pointedly syllogistic, mathematical flashcard or popular-scientific Safari Card formatted (page numbers even drop out sometimes) fact-filled approach that structures your “How to Prevent the Greatest Dying” section. Could you describe your own lived experience finding, absorbing, assembling, arranging, writing austere (but also potentially persuasive, galvanizing) facts like this?

A few different angles come to mind. First, this might sound contradictory, but I don’t think we face a big information problem right now. Many polls and studies suggest that people have absorbed some basic gist of the science, but maybe can’t put it fully into words. One reason I wrote Eating Animals came in fact from having these feelings I didn’t know how to put into words. I knew a lot of people, both vegetarians and not, who had experienced some sort of ongoing struggle with questions of eating meat, who wished they had some relatively simple ways to talk about this with their families or their friends or even just with themselves. There is power in making something clear — even if it is already known.

And then of course there is still some basic misunderstanding with climate science, especially when it comes to animal agriculture. I don’t blame this on trickery or deceit. I have no idea why Greenpeace and the Sierra Club and Al Gore didn’t historically talk about meat. But now, thankfully, you see these conversations on the front page of The New York Times.

That also all somehow relates to me not mentioning animal agriculture for the first 60-odd pages in this new book. It felt highly suspect, even for me as the author, to get so far into this book without really mentioning its subject. I guess I worried about alienating people. So then I wanted the “How to Prevent the Greatest Dying” section to correct some basic underestimations of animal agriculture’s role in climate change. And I made serious efforts to pick statistics or information that might inspire someone to look up from the page and take a breath. I still find it amazing, for example, that when the Earth was just six degrees colder or six degrees warmer, it had mastodons roaming a world of ice, and palm trees in Alaska. I still find it amazing that the amount of animal products we consume right now would have required every person on the planet in the year 1700 to eat nine-hundred pounds of beef and drink twelve-hundred gallons of milk each day. I wanted to clarify and correct, but without numbing people, without losing that heightened relationship to a compelling story.

Well to pause now on a few particular facts: first, I knew this vaguely, but found it disarming to read here that eating an ounce of cheese causes almost twice as much CO2 emission as eating an ounce of chicken.

Being a vegetarian most definitely does speak to climate change. It makes your diet vastly better ecologically than if you eat meat. But if we take it as our goal to reduce global warming (more than to maintain some legible, morally pure identity), then doing whatever you can to limit eating meat helps to achieve that goal. So for example, if someone were to ask me for the odds that half of Americans will be vegetarians in 10 years, I would say: “Approaching zero.” But if someone asked for the odds that half the meals eaten in America will be vegetarian in two years, I would say: “I think that will happen.” And those two different scenarios get us to the same outcomes regarding the treatment of animals, the number of animals raised on factory farms, the amount of greenhouse gases emitted. Everything we most care about happens in either case. So here again: indulging narcissistic inclinations to feel proud of how we describe ourselves (in contrast to somebody else) shouldn’t get in the way of broader social change that can do the most good.

So still on the facts here, could you clarify one numerical snag for me? Your assembled stats seem to suggest that a vegan-before-dinner diet would reduce an average individual’s CO2 footprint by 1.3 metric tons per year, getting an average American only seven-percent of the way towards our recommended footprint — if we wish to stay within the Paris accord’s two-degree goal.

Yeah, that gets us to an important point about how much Americans differ from average global citizens. The US military alone makes it impossible for the average American citizen ever to meet the recommended carbon footprint. And we’ll also have to sort through not just different footprints for different countries, but for different citizens within one single country. And in terms of this starting point, with Americans so far from where we need to be, I do see this book as very much focusing on individual action. It touches only lightly on, say, legislative action. Though of course we need both. Of course we need a carbon tax and we need new kinds of personal habits. Here I like the analogy to “homefront” efforts. These efforts won’t win the war, but you can’t win the war without them. A leaked forthcoming IPCC report already says we have no hope of getting where we need to go if we don’t also dramatically rethink land-management, farming, and meat-eating.

To return then to this book’s formal arrangement, but now focusing on kinetic movement (“getting where we need to go”) as much as thematic content: your opening section’s baroque buildup to its surprisingly spare and straightforward dietary recommendation (no animal products for breakfast or lunch) does stand out. You then offer nuanced claims for how much simpler this one individualized intervention would be compared to coordinating complex industry-constraining international treaties. You then pause on how difficult it in fact remains to get substantial numbers of people to change lifelong habits “freighted with pleasure and identity.” So here could you describe how that early pivot in We Are the Weather’s seemingly single-minded, agenda-driven project might evoke both the comparative ease and the residual difficulties of this one recommended lifestyle change — and the type of reflective trajectory that might take us there?

Sure I’d start from the baseline that none of this will be easy. Converting our electrical grids will not be easy. Supplying renewable energy to the entire world will not be easy. So I’d like this book to ask questions more like: “Hey, do we want these difficult tasks chosen for us, or do we want to choose them ourselves?” And then how does one compare the challenge of giving up steak tacos for lunch to giving up Miami? Or maybe I should use a city…

I like Miami. Go ahead.

I happen to like Miami too. I like the hotels.

Great sneakers.

I can’t stand the basketball team, but I’d save the rest. In any case: it just feels more honest and more energizing to acknowledge that the free ride is over. And whether we choose to pay at the cash register, or we pay by getting busted for what we’ve stolen, we’ll soon have to pay the price.

Again in terms of that comparative approach, I’ve described this book as meditative, and I wonder about potential philosophical and spiritual precedents from Augustine to Montaigne to Pascal to Simon Weil to Edmond Jabès — foregrounding the expression of doubt, the posing of unanswered questions, as you and as we ruminatively linger on what it might mean to (“instead of traveling beyond the horizon”) “venture into our own consciences and colonize still-uninhabited parts of our internal landscapes.”

I did want this book to record my own doubts. I entered the book with doubts. And I feel like the book ends…forget the question of what the human species will do — I still feel uncertain about what I will do, and what I will contribute. I find that fact disappointing but also sort of thrilling. I’ve reached a point somewhat similar to Justice Felix Frankfurter in this book, when he receives proof of Nazi concentration camps. He doesn’t deny that truth. He doesn’t deny his own inability to respond to it. He just doesn’t respond. And I too feel I’ve reached the point where I can’t deny my awareness about the workings of the world or the workings of myself. And hopefully that awareness keeps the conversation going in my mind, and propels me to move in the directions I should move.

So here could you say more about how this lyric embrace of internal plurality might help to steer us around stifling dichotomies in today’s climate discussions — which for too long, for example, have prioritized our contextual placement “in” an ecosystem over our existential interdependence with an ecosystem? Could you unpack a bit how such a dialogic sensibility might help to bring forth and make concrete this book’s “Dispute with the Soul” section’s statement / questions: “No one will cure climate change? Everyone will cure climate change?”

Right. Good question. Why do you think that works for people? I agree with what you just said about the importance of presenting a plurality of internal voices. But what makes that persuasive?

I think listeners might have a better chance then to embrace their own internal plurality, and to admit that they don’t have one-hundred-percent confidence or certainty or conviction either.

I basically share that answer. And I do wonder a lot how somebody else’s doubt can create uncertainty in you, and somebody else’s certainly can create a kind of reflexive skepticism or reticence or need for distance. I actually find this all pretty humbling. If you say to somebody “I’m not used to discussing it this way,” or “You’re showing me a different perspective,” those little rhetorical pivots can make all the difference. I don’t mean as manipulations. I mean as a way of sharing with someone who seems so different from you a kind of humility and openness.

Finally then, in terms of more personal reference points: my wife, a nutritionist, gets annoyed by diets that encourage us to project ourselves towards some unobtainable or unsustainable identity — to distract ourselves from more modestly, more practically, more consequentially reshaping our everyday circumstances. Within that spirit, could you describe some recent real-life adjustments you’ve made in order to more thoroughly carry out this book’s relatively simple dietary recommendation?

Right, I think of all these approaches to eating “naturally.” But what would it mean for us to behave naturally? Should I throw away my eyeglasses? Do they force on me some perverted vision of the world? Or do they make my life much better?

And in the case of diet, these questions stand out even more, since our diets have changed so radically in the past 50 years. Americans today eat 180 times as much chicken, per capita, as we did a century ago. Did we just all of the sudden realize that we naturally crave chicken? Or did we at last encounter a form of chicken you can eat without silverware in a moving automobile? I would argue that factory farming has encouraged a very unnatural kind of eating: unnatural in the types and volumes of food, unnatural in its impact on our human bodies — causing huge increases in heart disease and cancer.

So some people might imagine a recommended path here that ends with us eating seaweed pills. But I actually want to point down a path that leads us to eating more like our grandparents ate. Ultimately, that doesn’t have to mean becoming vegan for breakfast and lunch. But it does mean dramatically reducing the amount of animal products that we consume. According to our most comprehensive study of the relationship between food and climate, published at the end of 2018 in Nature, while people living in undernourished parts of the world could eat a bit more meat and dairy, Europeans and Americans need to reduce red-meat consumption by about 90 percent, and dairy by 60 percent. So one doesn’t have to adopt the model that I propose in this book. I just wanted to outline an approach that’s pretty easy to remember and pretty easy to maintain.

But most of all, I wanted to focus on reaching our destination, not perfecting our process. We do have to agree together on reaching this future in some non-controversial, unambiguous way. That’s an inflexible reality. But how do we get there? I have great respect for people who offer other ideas about how to get there, as long as these ideas are viable.

Philip Roth once told this great story about the Franklin Mint proposing a deluxe edition of one of his books. They asked him to sign, I don’t know, 5,000 copies. He said: “No thanks, not interested.” Then they mentioned how much they would pay him. And he thought: God, I could put a pool in my home for that amount of money. So he said: “Let me think about it. Who was the last person who did this for you?” They said John Updike. So he called Updike, and asked, “What’s the deal with this? Signing all those books sounds like a terrible fucking drag. Was it worth it?” And Updike answered with one word: “Just.” As in: it’s just worth it. A lot of big life decisions work this way. We might imagine momentous landslides, but then we encounter something just barely worth it, just barely possible.

For now, for me, the solution I wrote about in this book feels just barely possible. It also often feels difficult, and unpleasant. It often goes unnoticed. But I can do it. It’s not a monumental landslide, but I can. For me that felt like enough, and felt worth sharing.

Portait photo above by Jeff Mermelstein.