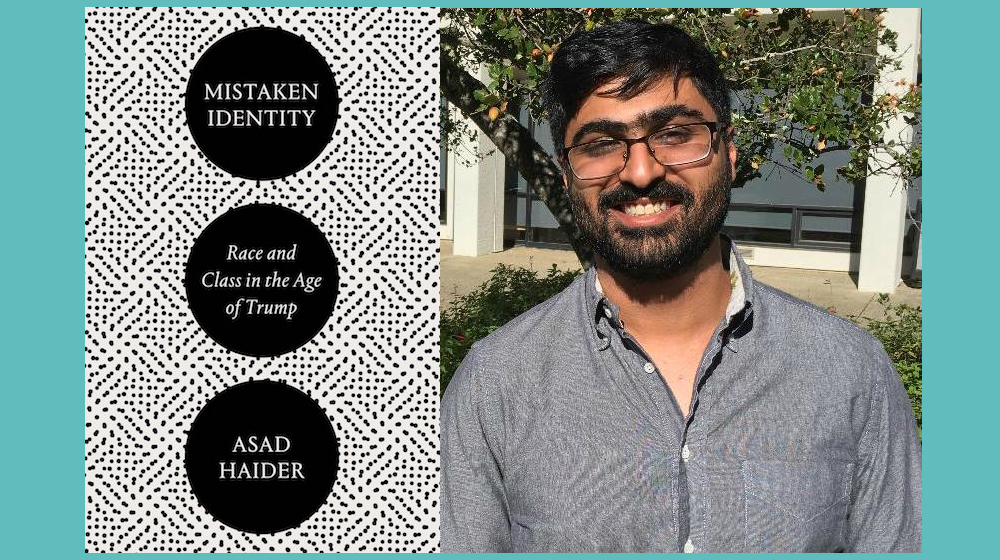

From where might a non-Eurocentric notion of universality arise? From where might we draw a new language to describe a different kind of collective politics? When I want to ask such questions, I pose them to Asad Haider. This present conversation (transcribed by Christopher Raguz) focuses on Haider’s book Mistaken Identity: Race and Class in the Age of Trump. Haider is a founding editor of Viewpoint Magazine, and a postdoctoral fellow in Race and Diversity in Penn State University’s Philosophy department.

¤

ANDY FITCH: Your book opens on the autobiographical, yet complicates our absorption of any straightforward personalizing anecdote, soon stating “I’m not so sure I emerged from this experience with anything resembling an identity,” and then more concretely (if no more conclusively): “Between the white kids in Pennsylvania who asked me where I was from (not Pennsylvania, apparently) and the Pakistani relatives who pointed out my American accent, it seemed that if I did have an identity, no one was really prepared to recognize it.” Here could you start taking us through this lived experience leading up to you asking not “Which identity do I have?” or even “Which of my many overlapping identities do I wish to foreground in which particular contexts?” so much as “What prompts me to formulate these social observations and introspective reflections in terms of identity?”

ASAD HAIDER: That sums up well a question people have about my book, which provides a critique of identity as a category, but which at the same time begins by talking about my own identity, and which takes my identity as the basis for developing certain theoretical points, and for opening onto certain historical problems. I start from the theoretical premise that lived experience is an effect, not a foundation — and that the same can be said about identity. The early discussion of whether my own identity gets recognized raises broader questions of recognition that become central to the analysis that follows.

I also describe how my identity is not located in a fixed place, but suspended between places — so again identity as an effect, though still a very real effect (I don’t claim that identity is all an illusion). The narrative at this book’s beginning starts in that lived experience, even if it then sort of unravels into various social constituents of this lived experience.

So again, in terms of complicating any easy grasp of Mistaken Identity: readers who instinctively align your critique of “identity politics” to some empty rhetoric of equal opportunity (or of universal brotherhood) might find themselves surprised to see chapter one open by presenting the Combahee River Collective’s classic “A Black Feminist Statement” piece as a “brilliant” demonstration of how interlocking modes of oppression necessitate articulations of “‘the real class situation of persons who are not merely raceless, sexless workers.’” At the same time, readers accustomed to citing Combahee as precedent for their own intersectionality-emphasizing mode of making the personal political (and vice versa) might find themselves challenged by Mistaken Identity’s account of how prevailing forms of identity politics neutralize any potential mass movement to resist racial oppression. So could you here reintroduce Combahee’s politics as you conceive of them — calling on us perhaps less to parse ever more singularly one’s categories of identity, than to extract, from our own lived sense of personhood, a richer, more analytic, more inclusive social practice?

First, to the question of elaborating a bit on my critique of identity: I do recognize that identity is a real effect. I don’t limit myself to saying that there are many ways of conceiving identity, or that there can be a good identity politics and a bad identity politics, and so on. But I do argue that a conceptual unity, as articulated in our current moment, identifies identity politics as a particular thing — something I want to criticize and argue for moving beyond. Now when I describe identity as, nevertheless, a real effect of lived experience, this means we can’t simply ignore people’s lived experiences and the identities that they have formed to make sense of those experiences. We can’t just call these identities wrong or backwards or something like that. All of us will always have imaginary conceptions of the conditions that we live in — but this doesn’t mean that identity should serve as a foundation for politics. So I make that distinction. I think we need to be capable of criticizing identity as a foundation for politics, and also of acknowledging that there is an identity-effect which always remains in flux, suspended between places. Again my own particular experience forced me to recognize this fact. But I do not consider the experiences of migrants exceptions from the norm. Instead, migrants’ experiences prove the general rule that identity is never fixed.

In terms of the reception of this book, you’re right that readers often expect to see one of two things: either a defense of identity politics (which again can mean any number of things, depending on the context), or an argument that the emphasis on race and gender distracts too much from the real struggle to understand the primacy of class. Now, I don’t offer either of those conceptions, but of course people need to read the book to understand that. If they don’t read it, they easily can slot me into one of these two categories, and I have been slotted into both (which maybe indicates at least some modest rhetorical success) [Laughter].

It seems clear to me that identity (here a particular way of making sense of lived experience, a way that frequently takes aspects of race or gender as starting points) should not just be generally presupposed. And one equivalent problem I see in many defenses of identity politics comes from the tendency to take this definition imposed by one’s critics and to reclaim it — to say “Whatever they criticize, that is what we accept and affirm as our identity politics.” I consider that a mistake, too, insofar as we seek a broader, more emancipatory project. This broader emancipatory project should emerge independently, not defined by and not reactive to that kind of narrow definition of identity. This project should go beyond the scope of the kinds of politics that we imagine through the language of identity. This is a politics that addresses all forms of domination, not just class, but that nevertheless pushes beyond identity.

As you first started responding, I wondered about asking: “Can you give your richest conception of what identity politics could be, if you had a clean slate to define the phrase?” But as you continue, I ask myself: “Why even indulge that historical fantasy?”

Right, I would consider it a kind of linguistic voluntarism to believe that we can, through sheer force of will, create better definitions for things. Language doesn’t happen that way. The historical changes this phrase has seen have been pretty profound, and we can’t just make a leap and return to its origins.

Nevertheless, I do understand why many people want to return to the version of identity politics advanced by the Combahee River Collective. Combahee did not offer some highly generalized account of race and gender. Combahee advanced a specific political intervention within a specific political scenario. The Collective brought together individuals coming out of various mass movements: the feminist movement, the black-liberation movement, the anti-war movement, the socialist movement. Combahee pointed out how each of these movements assumed a kind of hegemonic identity. The feminist movement had framed women as white women. The black-liberation movement had framed black people as black men. This led to hierarchies, and to the circumscribing of political possibilities, within these groups. So Combahee’s idea of beginning with identity (not just any identity, but the identity of black women) meant disrupting those exclusionary hierarchies, and opening up a revolutionary vision.

But again it would be hard to take the Combahee River Collective statement, and to generalize its conception of identity politics to, say, white women. That would be totally illogical. The rest of the statement would be incomprehensible, because it offers a very specific intervention regarding a very specific kind of identity. So I see this yearning for a return to the origins of identity politics as understandable. But, from my perspective, it misses that quite specific original intervention.

On this topic of both locating quite specific historical interventions, but also using them to pose broader methodological questions: Mistaken Identity routinely refers back to traditions of African American resistance, as elemental for thinking through struggles against racial oppression within a U.S. context. But here again, you seem less interested in assembling a diffusive litany of past insurgent acts than in exploring how, as an author, most productively to move (and to move us) from abstract categorizations of identity (as parceled out by the state) to all the lived material conditions and historical specificities potentially obscured by any such stark legal framework. So as an example of your incisive interpretive approach, could we take one specific historical scene, that of Bacon’s Rebellion, and could you talk through how reflection on this particular uprising might redirect us away from the more anachronistically complacent question “What type of race relations existed between blacks and whites back then?” Could you take us towards the more historically illuminating and urgent questions: “Why and how does the U.S. arrive at defining supposedly strict racial taxonomies through the confoundingly fluid characteristics of skin color and related physical features? How does inventing not only a black race, but also a concomitant white race, prove foundational for obscuring and sustaining basic social contradictions within these colonies — colonies that, a century later, will claim to found a new nation on the ‘natural rights’ available to all people? And then how might contradictions within that never-implemented universalizing rhetoric carry through two centuries further, as the Civil Rights era starts to get rewritten as a triumphant march towards integration, rather than as the most recent resounding call for much more far-reaching collective action?”

You’ve pointed to something I consider methodologically crucial to this book. First, in putting together a theory of racism, I work with historical and concrete instances, rather than providing a general theory. I’ve been revisiting the foundational article by Stuart Hall, “Race, Articulation, and Societies Structured in Dominance.” I just got to Hall’s line about his method: “Racism is not dealt with as a general feature of human societies, but with historically-specific racisms.” That was an important guiding influence for me in writing about the formation of racism.

So in Mistaken Identity, I don’t look to these events for some general account of relations between black and white workers. I focus on Bacon’s Rebellion not as some kind of straightforwardly emancipatory event, since it in fact involves an attack on the indigenous population. Its importance is that it opens up a much broader process of inventing the white race, as a form of social control. I draw from Theodore Allen and Barbara Fields as I try to avoid two basic interpretive problems. First, what you described as a diffusive litany of events. Second, some abstract, unitary, trans-historical conception of racial identity. One approach would offer a kind of pluralism in which we face the difficulty of making constructive interpretive connections among these disparate phenomena. The other approach would dwell too much in overgeneralizations. But I do think that finding a concrete case actually can help you to construct a kind of general logic.

Still, in terms of your second question, I don’t look at the history of black resistance in the United States (or any other form of resistance) as something unitary, as something with a clear organic origin that has remained constant over time. Even within these particular practices to resist particular forms of racism, we find profound disagreements and debates. The Black Panther Party and the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, for example, differ sharply on who they present as the revolutionary agent in American society. Is it the lumpenproletariat? Is it the black factory worker? And we see some similar disagreements about tactics. Should one engage in open and direct confrontation with the state? Should one ever work alongside the state? All of this shapes quite different accounts of the social forces available in different political sites. So yes, I want to look at the specificity of these instances of resistance, rather than creating one unitary narrative.

Alongside Mistaken Identity’s focus on the factory floor, frequent references to academia stand out as providing, again, not just some random sample of your unsifted autobiographical circumstance, but a particularly illuminating model for thinking through the late-20th-century multicultural integration of America’s leadership classes. Your “Passing” chapter outlines more generally how individuals from this leadership class might secure a sense of authority amid one specific segment of society — passing, for example, both as “black” and as “above” ordinary blackness. Your “Contradictions among the People” chapter critiques more acutely theorizations of Afro-pessimism, for foregrounding an ideology of racial unity that obscures the actual class position of many Afro-pessimism proponents. Could you make the case here for why even readers not immersed in academia have much to gain by considering how ideologies of race continue to play out within this one particular hothouse setting? And, to be fair, where in academia itself, perhaps especially amid various modes of cultural studies, have you yourself found the most constructive social critiques aligned with some of the major concerns outlined in Mistaken Identity?

One thing I don’t do in this book is trace the genealogical depths of how the phrase “identity politics” comes out of these specific late-1970s contexts, and then takes us to discussions we hear today. Of course a specific history shapes all of this. In the 1980s, identity politics gets taken up by what were then called the “gay and lesbian movements,” bringing their own sets of debates and questions. For example: what happens when sexual identity becomes desexualized as it gets attached to broader reform projects? Or what happens when queer identity becomes affixed to some essentialist understanding? And similar questions of a supposed feminine essence already had persisted from second-wave feminism.

So in the 1990s, you get this quite complicated conversation. It’s a bewildering moment when all of a sudden it seems that identity politics as a social-movement term has fallen out of the picture, and now gets most vocally taken up by critics of identity politics. Identity politics becomes one pole within the culture wars, attached to critiques of political correctness. In this particular cultural moment, people begin to advance a conservative (or classically liberal) critique of identity politics, which implies certain very specific definitions. This phrase that had been loosely connected with the new social movements now becomes an object of academic dispute, and part of the politics of the academy — amid a right-wing attack on what was taken to be the radical politics of the academy, and a kind of left-liberal reaction against the influential role of the new social movements. Todd Gitlin and others who criticized political correctness and identity politics made the argument that these elements had brought about a broader failure of the left. They claimed that the new social movements had taken up disproportionate attention, and that because of this, the more classical elements of the labor movement and the socialist movement were undergoing a decline.

Now, this causal explanation, suggesting that nascent social movements led to the defeat of entire institutions like organized labor or left-wing political parties, is pretty unconvincing. It’s more logical to understand all of these movements and institutions as operating within common social conditions. My book tries to trace some of these social conditions in the section focusing on Stuart Hall. Of course Hall himself theorizes identity in ways Mistaken Identity does not directly address, but this is because I want to bring attention to his political analysis, which readers often have considered too specific to his context. Despite his canonical status in cultural studies, Hall’s political analysis wasn’t emphasized by the American reception. Hopefully that will change now, with his writings finally being collected and published.

Throughout the 70s, Hall tried to point to a crisis moment for the left, brought about by the economic crisis and the restructuring of capitalism, and also by what Hall called the crisis of hegemony — in which forms of state power had been put into question. At this moment, when the modes by which the state secured the consent of the population no longer seemed viable, new forms of securing consent and new forms of coercion were put on the table by the right (by Thatcher and eventually Reagan). At the same time, the left showed itself incapable of managing this crisis, and classical forms of the union and of the party were not able to meet the challenge of this political balance of forces. The debates over political correctness and identity politics happen within that particular historical context, bounded by those political constraints. That’s something I think a lot of people overlooked in the 90s, in the aftermath of those political defeats, especially when allowing these debates to be reduced to the various forms of etiquette that are appropriate in the academy — and then to the universalization of these manners.

For a comparative U.S. point of focus, and in terms of your own take on the legacy of late-Civil Rights-era initiatives, I’ll cite just one quite concrete, quite damning (yet also comprehensive, synoptic) passage:

The lingering ideologies of racial unity left over from the Black Power movement rationalized the top-down control of the black elite, which worked to obscure class differences as it secured its own entry into the mainstream. The black political class ascended in the seventies’ context of economic crisis, deindustrialization, and rising unemployment. A politics conceived solely in terms of racial unity precluded any structural challenge to the capitalist imperative to transfer the costs of the economic crisis onto labor. As black politicians facilitated the employers’ offensive, they turned against the working-class elements of their popular support.

We will have a lot to unpack there. But could we start from you assessing a movement’s anti-capitalist efficacy less by the stated issues it organizes around, than by the methods through which it draws in (or doesn’t draw in) a wide spectrum of participants, and enables their own individual and collective self-organizing capacities? And could you continuing reframing how single-issue social movements almost inevitably centralize their most privileged members, and how identity politics, as presently conceived, can’t help siphoning off more broadly emancipatory possibilities — as an emergent elite benefits by reinforcing (rather than unsettling) such categories of identity?

You’ve pointed to a kind of contradiction we have here, because even though the UK was somewhat exceptional in Europe for its low level of labor struggles, it still reached far beyond anything seen in the U.S. In the 1960s, we didn’t have any trend of socialists getting elected to office. Neither party pursued actual socialist reforms. We’ve always been far behind that. But in terms of the scale of mobilization and social change, the Civil Rights movement offers our best equivalent to Europe’s mass labor / socialist movements. And each of these various movements, in its own way, tries to advance the autonomy of previously dominated people. That project of advancing autonomy ultimately fits an anti-capitalist program.

And that struggle for autonomy remains essential in a capitalist society. Especially in Italy, a lot of Marxists in the 60s and 70s recognized this need, and wanted to learn about black movements in the U.S. People like James Boggs and John Watson of the League of Revolutionary Black Workers went to Italy and were received with great enthusiasm. These movements do share an intrinsically anti-capitalist point of reference. But the question then becomes, of course: what do these various groups mean by the pursuit of autonomy? It’s not as though these groups simply exist in and for themselves, absent any broader movement. The Civil Rights movement did influence a very broad spectrum of the population. You have a class of black elites, such as it exists up to the 1950s, exerting pressure, but you also have so many working-class black people taking part.

Then the Black Power movement in some sense arrives after the major legislative achievements of the Civil Rights movement, and tries to answer remaining social questions. The Black Power movement offers this ideal of racial unity, which unites the emerging black political and business classes with people picking up on the resistance displayed during the urban rebellions of the mid-60s. In this moment you see a lot of ambiguity about the different historical trajectories at play. So what is the relation between the emerging black elites and the existing power structure? Does a clear link exist between the elites and the mass of the black population, in terms of interests and demands that they can put forward? In this particular historical moment, the answer remains unclear. Retrospectively, we do see an incorporation of black elites into the existing power structure, especially manifested in the election of black mayors. We also do see an increasing separation between the interests of these elites and the mass of working black people. We see a lag between the material changes happening and an ideological understanding of those changes. Many figures involved in the Black Power movement try to account for this class differentiation within the black community. Often this means making a stronger turn towards Marxism, which I trace in the book, as a significant part of this moment’s historical trajectory.

Here again I want to clarify that Mistaken Identity does not summarily dismiss the value in oppressed peoples making the most of the racial categorizations (often, in your own formulation, “devastating” categorizations to contend with over a life) forced upon them — that your book doesn’t simply demand everybody renounce their racialized identities, but instead seeks to engage sensitively, and to harness as constructively as possible, the most restorative, resistant, radicalized elements within such identities. But if I had to pick one paragraph that might alienate many self-described progressive readers, it comes on pages 62 and 63, as you pivot from Paul Gilroy describing profound transformations of “‘insult, brutality, and contempt’” into “‘important sources of solidarity, joy, and collective strength’”; to Judith Butler detailing the individual subject’s “‘passionate attachment’” to power; to the stark conclusion: “This is the kind of attachment that children display toward their parents, who are an arbitrary repressive authority but also the models of selfhood and the first sources of recognition.” Your subsequent paragraph does spread this pathologizing diagnosis more universally, by opening: “We are constituted as subjects within the individualization that is characteristic of state power; we are activated as political agents through the injuries that are constitutive of our identity.” But could you speak to this particular pivot to the collective “we,” to everybody’s social / political identity emerging amid traumatic processes, and to how difficult it will remain for a long time to come for anybody to discuss, from some supposedly detached rational perspective, these “imaginary representations of our real conditions, of structural transformations and the political practices that respond to them”?

Okay, so by “imaginary” I don’t mean an illusion or a fiction. By “imaginary” I want to describe just a basic fact of power, which comes from our perceptions being limited. We will always have limits on what we can perceive, and which causal mechanisms we can understand. Things happen to us, in specific ways, and we can’t always recognize their causes. So we necessarily make imaginary representations, since our relation to the world out there exceeds our understanding. That’s not unique to racial identities. That’s a general condition. But our conceptions of race do provide a particularly clear example of this process.

Our common-sense understanding causes us to think of race as something visible in appearance. We perceive race through skin color, hair, facial structures. We think of racial identity as some foundational part of who we are, contained within us. But this imaginary understanding can’t possibly extend to an understanding of the historical causes for these racialized descriptions. When we conceive of ourselves as white, Pakistani, and so on, those labels don’t actually tell us about the historical invention of the white race in 17th-century colonial Virginia. No matter how much you reflect as a white person, no matter how guilty you might feel, you won’t arrive at a complete understanding at this level of an imaginary conception of yourself.

So when I discuss race as an imaginary representation of real conditions, I mean to describe this cognitive and perceptual process. Now, the fact that we should study this set of real material and historical relations doesn’t mean that imaginary representations will go away. But we can change our relationship to these imaginary representations. We can understand better why racial identity can’t explain the whole of who we are, and can’t function as the true foundation for a political program. Again, this doesn’t mean race just goes away, but this changes the way we relate to race. We no longer feel governed by it. We still might, as Paul Gilroy pointed out, make the most of our assigned racial identities, and turn them into a force of self-defense. At the same time, though, we recognize how this set of racial identities reproduces an oppressive hierarchy. We ultimately have to put that entire hierarchy into question. Gilroy does this very beautifully in his books, in part by depicting the hybridity and the instability of racial categories, making it possible to break out of this ethnic absolutism and cultural nationalism — in order to form newly hybrid practices of resistance.

At first I wondered to what extent you might be cherrypicking when Mistaken Identity then traces the American Communist Party’s apparently visionary anti-racist engagements across the 20th century. But as I progressed through the book, I appreciated your nuanced attention to oscillating intellectual arguments and organizational approaches for how U.S. socialisms of various sorts would at times cogently resist, and at times patronizingly reinforce, racial hierarchies. I found especially illuminating your account of a mid-century American left context in which, amid the absence of momentous mass organizing, racialized ideology rushed in to fill the vacuum — with, say, Communist Party proponents of such ideologies policing white chauvinism, while simultaneously sowing paranoia and distrust among Party members. Could you place that particular historical moment in relation to our present, and then perhaps lead us to Theodore Allen and Noel Ignatiev re-articulating a call to much broader modes of collective action with their 1967 White Blindspot pamphlet, which picks up on W.E.B. Du Bois’s critical precedent, even as these authors make their own, updated case that struggles against white supremacy have to struggle for universal emancipation, for no second-class-citizen status for anybody?

So I think that the relationship of socialist movements in general to black people, and specifically to black-liberation movements in the U.S., has been very complex. It’s easy to absorb this history too reductively in one way or the other. When it comes to the Communist Party, a long tradition of Cold War scholarship assumed that everything Communist parties did came directly out of some manipulation from Moscow — even in Europe, where at times you had millions of members. That interpretive approach problematically obscures the heterogeneity at play in various Communist parties, and their complicated relationships to the Soviet Union.

I briefly mention, for example, one major black communist, Harry Haywood, who is a very interesting figure, partly responsible for the thesis advanced in the late-1920s and the 1930s that the U.S. South constituted a black nation, a nation with the right to self-determination. That single thesis already shows many different facets to this whole debate. Many commentators called Haywood’s thesis a vulgar transposition of the category of “nation.” But a whole history exists in the U.S. of movements (typically dismissed as sectarian and crazy) who try to present new versions of Haywood’s theory — as one method for attempting to understand and respond to the oppression of black people in the U.S.

I don’t accept the view which ridicules and dismisses this approach, because that dismissive view relies on the presumption that race is a natural, self-evident, coherent, and stable category, while a nation presumably is not. Such a view does not really offer a critique. It just reflects an ideology. You have to actually construct the meanings of “race” and “nation” from the ground up, and understand what they do, how they intervene in a given historical situation. And in fact, when you present a materialist critique of racial categorizations, a critique of national categorizations often follows close behind. Historically these terms are debated back and forth, both nationally and internationally, even as the American Communist Party does focus quite vigorously on anti-racist work — building sharecroppers’ unions, the Scottsboro Campaign, anti-lynching campaigns, and so on.

We have a regrettable tendency to look at texts coming out of these social movements and to treat them as purely instrumental, without really considering their theoretical content. We track the practical effect that an idea had, but we don’t necessarily engage the serious theoretical issues that it raises. A lot of room still exists for us to engage in more creative study of how the Communist Party tried to theorize their anti-racist work.

Again the White Blindspot pamphlet seemed particularly interesting in that regard.

Yeah, the initial theorization of the concept of white privilege is a pretty amazing discovery if you don’t know where that language comes from. That concept first means something almost opposite of what it means today. It first describes how this extension of short-term privileges for white people actually maintains their subordination to capitalist exploitation, and it argues that whenever white people participate in the oppression of black people, they also undermine possibilities for their own liberation.

Now, that reasoning results in a pretty unambiguous conclusion for why whites should feel the obligation to oppose white supremacy. But today’s looser conception of white privilege basically stresses that white people should check their privilege, that they should feel guilty about it. That’s pretty much it. It’s not clear what that accomplishes politically. When white people feel guilty and “check” themselves, the political goal supposedly has been accomplished. But that suggests a very constrained idea of what is politically possible. I would generally criticize in identity politics this comfortability with never actually undermining racism. When this becomes an affective project, when it becomes a project of getting recognition, of producing sad emotions in somebody else, the project of actually changing the system has disappeared.

So what will it take for white people (because they’re not going to be eradicated, or to collectively fall silent) to take an active role in deposing white supremacy, instead of passively reproducing it? It will take finding new ways of building connections across racial divisions, new mass movements that can make broader demands against domination. Without that collective basis, we cannot hope to successfully combat racial hierarchies. Meaningful legislative reforms require an active social base demanding them and applying pressure to the state. The state will not simply reform itself, even when certain leaders claim they will pursue these programs. They can’t and won’t carry through these reforms unless the social base demands them. So if you want to make reforms that undermine racism, you can’t get around the need for a mass movement built across racial identities.

Could we here move towards Paul Gilroy’s “strategic universalism” concept, and outline a strategically universalized approach you hope to help cultivate going forward: a strategic universalism perhaps always created / re-created through acts of insurgency, a strategic universalism insisting that emancipation is self-emancipation, a strategic universalism tapping what C. L. R. James might describe as “the always unsuspected power of the mass movement” (yet perhaps retaining some skepticism regarding our nostalgia for preceding forms of mass mobilization, forms not necessarily optimal for addressing present circumstances), a strategic universalism most acutely attuned to broader social structures to resist or rebuild — rather than to an authenticity of experience to police?

To me it’s an axiomatic starting point that the goal of any oppositional political movement should be universal emancipation. It’s not generally described this way in the U.S., but, throughout the world, identity is often understood as the source of social violence — not just oppressive state violence, but widespread sectarian violence. At the same time, we face the problem that the concept of universality remains so closely associated with European dominance. And while my book opposes any foundationalist approach to identity, I also oppose any foundationalist approach to universalism, grounding it in the abstract person with universal rights, participating in the nation-state, participating in the market, and so on. Marx criticized this conception quite effectively, and many others have since shown us further how this notion of the abstract person does not derive from any natural foundation, or natural condition, but gets produced through the atomization of the individualizing marketplace, and then projected back onto nature. The rights we associate with this ideology don’t just belong to us naturally. This is why so many declarations of rights get declared by nations which hold slaves as property. That’s because rights are not actually endowed by our creator, but are won through social struggles. That’s why even at the level of the market itself, even when we associate capitalism with free wage labor, and with wage-laborers entering into voluntary contracts, a lot of research actually shows that in industrial-revolution England, many wage-laborers were burdened by contract laws that restricted their ability to leave their employer.

The classical European conception of “universality” remains very much embedded within this ideology of the emerging capitalist society. We have to look elsewhere for a kind of universality that doesn’t restrict its rights and its citizenship to wealthy white men. I give some examples. The Haitian revolution, for instance, exposes the particularism of the French Revolution. In fact it activates a process through which French groups excluded from rights also engage in insurgency, also put their agency on the table. That’s the kind of universality we have to start talking about and begin to identify in history and in our own political practices. It definitely goes beyond Europe. It offers possibilities to locate where a new universality might start to emerge.

In terms again of progressing from obfuscating abstract categorizations of “the person,” to more catalyzing concrete circumstances: until late in this book, I wondered whether you ever would push beyond the seemingly mystified term “people,” which often here hints at, without really delivering, some potentially decisive majority just waiting to be called into being. I wondered to what extent these loose references to “people” might in fact prevent you from maintaining your own rigorous standards of not reducing “any group of people and the multitude they contain to a single common interest.” So I especially appreciated, in your concluding “Universality” chapter, the distinction offered between “ethnos” (a plurality suppressed by some myth of unity) and “demos” (a collective decision-making community). Could you expand on that distinction here, perhaps by clarifying the emotive power that the term “people” held for you as you wrote this book, and how you might envision yourself continuing to engage and explore “people” in future projects? Who precisely are the real-life people making up the collective decision-making community that you reference and / or that you long for?

There is this problem of how to refer to some kind of collective agent. There’s also a problem of the relation of this collective agent to other institutions or entities — most commonly the nation. We could say that Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri made this problem famous by looking at how to translate the Latin term multitudo as “the masses” or just “multitude.” Populus gets rendered as “people,” and describes in some ways this multitude reconfigured and unified by state sovereignty. Hardt and Negri argued that “the masses” was too unifying a conception, that it erased differences too much. I don’t know if there’s anything special about “multitude,” other than that it’s relatively uncommon in English.

But each of these terms gets used in some way to point to a collective agent, and “people” has that nationalist foundation — of “We the people,” and so on. Nationalism, in other contexts, has been part of a struggle against imperialism. The Black Panther Party would speak a lot about “the people,” because they initially aligned themselves with the project of national liberation. This language of “the people” makes a certain sense, and its particular underpinnings, national or otherwise, can be transformed in political practice. An exemplary historical case is the Chinese Revolution, where “the people” constantly gets redefined, as the political subject working towards national liberation, revolution, or socialist construction. You pointed to an earlier chapter’s formulation of “contradictions among the people,” a sort of wry reference to Mao’s essay about “the correct handling of contradictions among the people.” That’s just a bit of my own distancing from some romantic conception of “the people.” I think a lot of questions ought to be raised about this word, just as with “the masses,” “the multitude,” and so on. But despite this difficult legacy, despite the fact that these phrases all may sound contrived in contemporary political language — despite all that, they still point to something we can’t escape, which is that to conceive of a different kind of politics, we have to conceive of a different kind of collective agency. We may not have yet found the language for that, but this problem still stares us right in the face.