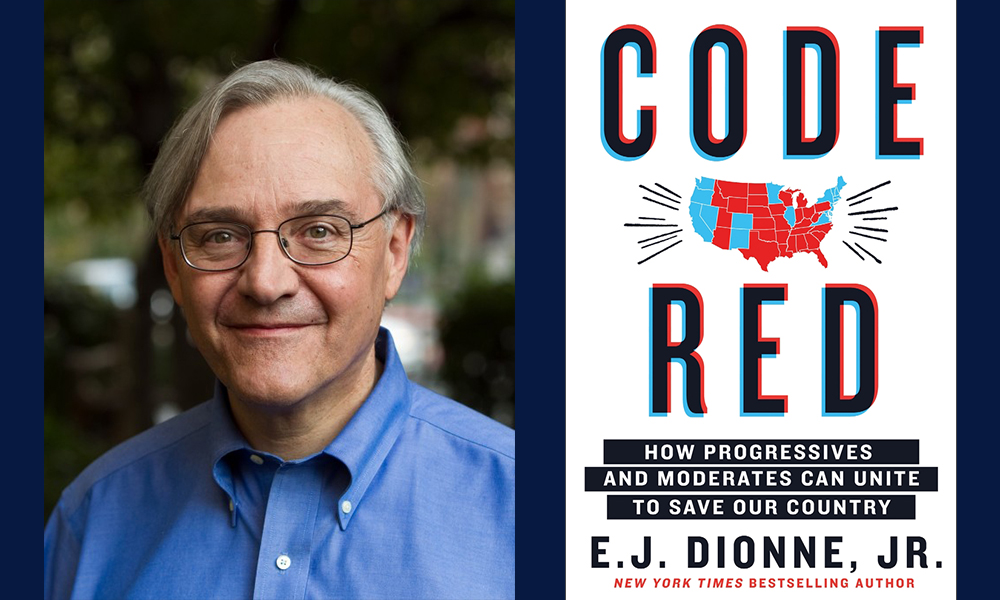

Where should Democratic moderates turn when they have no Republican moderates to debate? Where should left-leaning progressives turn when they no longer can take for granted basic democratic functioning? When I want to ask such questions, I pose them to E.J. Dionne, Jr. This present conversation focuses on Dionne’s book Code Red: How Progressives and Moderates Can Unite to Save Our Country. Dionne is a columnist for The Washington Post, Senior Fellow at the Brookings Institution, visiting professor at Harvard University, and professor at Georgetown University. His recent books include One Nation After Trump (with Norman J. Ornstein and Thomas E. Mann), and Why the Right Went Wrong.

¤

ANDY FITCH: Let’s say today’s Democratic moderates (however you want to define that term) have no critical mass of moderate Republican officeholders with whom to compromise. Let’s say today’s progressives (again however you want to define that term) lack the luxury of offering a largely idealized agenda while resting assured reasonable participants from both major parties will hold our basic social compact together. Within that present context, could you sketch several distinct opportunities you see for a Democratic Party which has temporarily “cornered the market” on a responsible reform-minded politics — as well as several fundamental challenges the party faces while serving as the staging ground for pivotal national conversations on what such reforms should look like, and what they might require?

E.J. DIONNE: Thanks for doing such a good job summarizing one of the book’s central arguments, which starts with how the Republican Party’s radicalization has created this enormous structural problem for our democracy. When Democratic Party debates feel so fractious right now, we have to keep in mind that constructive debates between moderate Democrats and moderate Republicans just don’t exist today. Instead, any reasonable reform-minded discussion gets carried out entirely within the confines of the Democratic Party — or among progressives. So moderates and progressives absolutely need to find productive ways of working together.

Take healthcare as an example. Obamacare itself came out of conservative proposals for expanding coverage. Obama embraced ideas from Mitt Romney’s Massachusetts plan, and from the Heritage Foundation, and tried to design a market-based approach — which still didn’t get us all the way to universal coverage. Back in the 1970s, Richard Nixon already had put forward a healthcare plan far to the left of what Obama thought our political system could bear. So today we see arguments within the Democratic Party itself over whether to keep building on Obamacare, to add a public option, or to go all the way to a single-payer “Medicare for All”-type national system. But note that every side in the Democratic discussion now agrees that the goal should be decent, affordable health insurance for everyone.

And before this understandably impassioned healthcare debate consumes us, we also need to step back and recognize collectively the threat that Donald Trump poses to the rule of law — and in the long run to democracy itself. Progressives and moderates have no practical alternative but to work together, because regardless of what they don’t hold in common, they do share a belief that we need to stop Trump, and reverse the direction of our politics. Similarly, from a broader historical context, progressives and moderates need to see that differences between them pale in comparison to their shared differences not just with Trump and Trumpism, but also with this radicalized force that the American right has become over the past several decades. This book’s first sentence asks: “Will progressives and moderates feud while America burns?” (which, by the way, is literally true, to use a favorite Joe Bidenism, because of the dangers we face if we don’t address climate change).

Could you likewise make the broader case for why any emergent left-leaning coalition cannot choose between either a politics of restoration or a politics of transformation: particularly as we seek to stop runaway inequality, to catch up on addressing climate change, to retool democratic functioning, and to deflate today’s more dangerous populist passions?

We need restoration because, as the left, the center-left, and that brave group of anti-Trump Republicans (who tend to operate outside of Congress) recognize, we cannot stay on this same path. And I truly believe a broad range of Republicans understand this also: that restoration means a Justice Department that puts the rule of law above the president’s immediate political schemes. Restoration means the US again standing up for democracy around the world (even as we acknowledge all of the flaws and failures in how we’ve done this historically). Restoration means ending the systemic corruption we see in everything from the Trump hotels to the president’s questionable relationships with a variety of foreign despots.

So we desperately need to restore certain norms. Yet we also need transformation, because this Trump presidency didn’t come out of nowhere. In recent years, the Republican Party has given in on some hardcore propositions Trump put forward, whether on immigration or a racial politics. But as many have said, Trump just traded in the old Republican dog whistles for the bullhorn.

At the same time, progressives and moderates have to take seriously another reason Trump won, which has so much to do with inequality. We need to maintain focus on racial and gender inequality, as powerfully corrosive forces in American society. But we also need to address the enormous social costs attached to severe economic inequalities that have spread across whole regions of our country.

Surveys analyzing Trump voters have tended to focus on racial backlash, immigration, and partisanship. But if you look at geographical studies, you see quite clearly that regions falling behind economically ended up voting for Trump. My Brookings colleagues offered the illuminating statistic that Hillary Clinton carried only about 450 counties, but that these counties represented 64 percent of our national GDP. Trump carried roughly 2,500 counties, representing the remaining 36 percent. When we don’t take real steps to uproot that kind of inequality both at the individual and regional level, we’ll inevitably face this sort of fractious politics. Some parts of the white electorate were willing to turn to a figure like Trump, out of sheer frustration and demoralization. So again we do need restoration to reverse our current self-destructive course. But we also need transformation to enable us to move forward, to get us out of the mess that helped create this Trump presidency in the first place.

So where might progressives in fact find it useful to frame their economic project as the restoration of an egalitarian American democracy committed to fending off domination by concentrated market powers? Where might moderates have the chance to frame their own political project as in fact transformational, securing a sturdy base for the ongoing implementation of America’s most aspirational long-term visions? And how might those two perspectives entwine themselves as elemental strands of a “visionary gradualism”?

In the book, I describe both moderates and progressives today wanting to restore progress. This is where those we might call “restorationists” and those who are “transformationists” come together. The word “again,” for example, doesn’t just appear in Trump’s “Make America Great Again” slogan. You also find it in the John F. Kennedy slogan “Let’s get America moving again.” “Again” doesn’t have to be a reactionary word.

More broadly, I do see in US history this very powerful dialectic (if you’ll forgive my use of that term) between what progressives do and what moderates do. Bernie Sanders’ support of Medicare for All, and free college, and the Green New Deal (alongside many of Elizabeth Warren’s ideas, particularly on the wealth tax) have transformed the debate in crucial ways. We desperately needed to move beyond the Reagan economic consensus. Sanders and Warren have both drawn large-scale support because so many Americans (and not just on the left) have felt deeply frustrated for decades now at the degree to which moderates kept compromising with this Reagan-consensus vision of deregulation and low taxes. Conventional definitions of “the center” had shifted pretty far to the right. But today you see moderates responding to Sanders and Warren by moving in a more progressive direction.

Bernie has argued rightly that there’s nothing inherently impractical about single-payer healthcare, that it’s in fact quite popular and successful in many countries — although I’d add that some of them (Switzerland, the Netherlands, Germany, and Australia, for example) cover everyone with good health care through mixed systems. Joe Biden’s healthcare plan looks far more progressive than Obamacare. The public option, which a few moderate Democrats managed to kill during the Obamacare debate, has now become the moderate position. That’s enormous progress in the public debate, from my point of view.

Similarly, we may not move instantly towards free college, but this wouldn’t be as revolutionary as people might think — given that, say, California residents could attend college at virtually no cost during JFK’s presidential term. But we can and should debate how quickly to move there. Biden, for example, routinely follows Barack Obama in saying that he first wants to make two years of community college free, as a kind of down payment. You also see bold proposals from more moderate candidates to alleviate the burden of student debt. So here again we already have these two sides engaging in productive dialogue.

There’s nothing radical about universal health coverage. There’s nothing radical about free college. There’s nothing radical about taking bold steps on climate change. All three of these actually sound like realistic and well-tested (rather than idealistic) policy approaches. On the other hand, I do think moderates should make their own distinct case for how we can take a very significant step towards alleviating inequality by introducing a public option for healthcare, how we can vastly expand access both to college and to post-secondary training for people not headed to college, how we can halt and reverse climate change while building broad social consensus. Here I use the “visionary gradualism” phrase invented, ironically enough, by the democratic socialist Michael Harrington, whom I admire enormously.

I have no illusions that people will march in the streets under this banner of “Visionary Gradualism.” But I think that phrase embodies what each side gets right. The left argues correctly that if you fail to propose reforms big enough to deal with real problems, then they’ll fail to rally popular support. Moderates argue correctly that at many moments in our history, when we’ve needed to take big steps forward, we got there not in one single leap, but in several stages. Social Security passed under Franklin Roosevelt still excluded large portions of society, most notably many job titles held by African Americans (which shows that, even in a progressive period, fighting racism remains absolutely essential). But that initial establishment of Social Security did provide a politically popular structure for redistribution, which has endured over time, and has expanded under both Democratic and Republican administrations into the program we know today.

To start pivoting then to concrete political outcomes, first what did 2016 teach us perhaps both about how moderation alone can’t work (even against a glaringly uncivil opponent like Trump), and about how a progressive turning up of the nose at one’s fellow Americans (including many members of the supposed Democratic base) can lead to disastrous electoral results?

First of all, 2016 should show us that the so-called Trump base is itself smaller than often described. On Election Day, Donald Trump had an unfavorable rating of 60 percent, but Hillary Clinton had an unfavorable rating of 55 percent. In fact, according to exit polls, 17 percent of voters had a negative view of both Clinton and Trump — and this 17 percent decided the election in Trump’s favor. Some of these votes no doubt came from partisan Republicans. But many came from people who, for a variety of reasons (for some sexism, or being tired of the Clintons, and of course James Comey’s intervention played a big role), just couldn’t get themselves to vote for Clinton. So I do believe we should think of this supposed Trump base as smaller than many would have it, especially more than three years into this country’s experience of a Trump presidency (and of course Trump’s handling of the coronavirus will do nothing to help him).

We also should keep in mind that the Clinton campaign actually offered a much more inclusive and progressive policy agenda than a lot of voters recognized. Clinton’s campaign never adequately laid out the extent to which this policy agenda reflected a real effort to begin reforming the economy — on behalf of many people who ended up voting for Trump, in many parts of the country that voted for Trump. The Clinton team never really made that economic program central to their campaign. Research by Lynn Vavreck, a political scientist at UCLA, has shown that roughly one-third of Trump’s television advertisements mentioned the economy in some way, whereas only about one-tenth of Clinton’s did.

Hillary Clinton does get a bad rap to some extent. Early in the campaign, for example, she gave an extraordinary speech in West Virginia, saying that West Virginia might not vote for her, but that she would stand up for the people of West Virginia and other hard-hit places. Anything she said about this kind of economic agenda of course got wiped out by the word “deplorables.”

Still, as I argue in the book, we need to move beyond engaging in this kind of either/or debate about whether racist nativism or economic populism motivated Trump voters. Undoubtedly racial backlash played an important role. We shouldn’t pretend otherwise. On the other hand, we shouldn’t fool ourselves into thinking the Trump electorate found its sole motivation in racial animus. A significant number of discontented Americans voted for Trump because they liked what he said about trade. They liked what he said about China. They liked what he said about restoring blue-collar jobs or coal jobs — even when Trump just lied or fabricated some economic scenario we know will never happen. Many middle-aged or older working-class men (but not exclusively men) thought they had made a deal with the economy, where if they worked hard, they would earn a solid wage and could retire with decency. But globalization and technological change broke that bargain. And we do need to recognize these voters’ aggrievement as a legitimate and powerful political force.

In Code Red, I write about Senator Sherrod Brown as a politician who speaks especially eloquently about these concerns. Brown built his whole recent Senate campaign around what he called “the dignity of work.” Brown doesn’t compromise on civil rights. He strongly supports African American communities in Ohio and elsewhere, and regularly attacks Trump’s racism and nativism. But working-class white voters in Ohio sense that Sherrod Brown knows where they’re coming from, understands their struggles. If you look at returns in the Youngstown area in Mahoning County, Hillary Clinton ran well behind Barack Obama in 2016. But Sherrod Brown restored the Democratic vote almost to 2012 levels. Democrats and progressives and moderates all need to pay attention to that.

Well what, then, did 2018 teach about how to get the moderate/progressive balance right: in an election characterized by noteworthy forbearance from both sides, in a decisive victory powered both by progressive mobilization and moderate persuasion, and in a Democratic majority shaped by realigned industrial-heartland voters and a suburban surge and an unprecedentedly high midterm turnout (especially striking among young voters and voters of color)?

I know others already have argued that we need to push beyond any narrow debate over whether you win elections through mobilization or through persuasion. You do need to get that balance right, in every single campaign. Some elections have a much stronger persuasion dynamic, and some have a stronger mobilization dynamic. In 2018, Democrats got the balance right. They mobilized their voters, with a great deal of help coming from Donald Trump himself. From Trump’s very first day in office, his opponents (both moderate and progressive) began to mobilize: first in the great demonstrations like the Women’s March in Washington, and second in continuing on-the-ground organization. Theda Skocpol, the Harvard scholar, has done excellent research on these on-the-ground efforts in the two years leading up to 2018.

At the same time, Democrats (including progressives) understood that, in certain suburban districts, in certain rural districts, only more moderate candidates could prevail. Those candidates engaged in a lot of persuasion: particularly on healthcare (with Republican efforts to repeal the Affordable Care Act reminding voters of crucial benefits they now receive from Obamacare), on the divisiveness of Trump’s politics (which does not in any way appeal to core suburban moderates), and, in many districts, on gun control. Those who support what I’d consider sane restrictions on firearms now have the upper hand in electoral politics, particularly in many swing districts.

Progressives ended up winning some of their most important victories in the primaries, with Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez being the best-known case, as well as Ayanna Pressley. Pressley (in the Boston area) and Abigail Spanberger (a moderate who represents the Richmond suburbs and some more rural communities) play important roles in my account of 2018. They are very different sorts of Democrats. Pressley, a former Boston City Council member, African American, very progressive, defeated a rather progressive member of Congress, Mike Capuano, with the great slogan: “Change can’t wait.” She kept making the case that Democrats had not gotten fully on board for how much change this country really needs.

Spanberger, who had worked for the CIA, ran a much more moderate campaign — emphasizing that, unlike the Tea Party incumbent, she would represent everyone in the district, including everybody who voted against her (which I recently learned was a line Abraham Lincoln used in his own Congressional race). But in the end, Pressley and Spanberger needed and still need each other. Pressley could not exercise power among a Democratic majority if candidates like Spanberger (alongside Chrissy Houlahan and Conor Lamb in Pennsylvania, Tom Malinowski and Mikie Sherrill and Andrew Kim in New Jersey, and the list goes on) had not prevailed all over the country. These moderate victories proved essential to progressives like AOC and Pressley gaining clout in Congress. But those moderates couldn’t have prevailed (and I quote some of them saying so) without the energy coming from the party’s progressive side.

You rarely have your book’s theories ratified at a public reading, but I gave a talk at Politics and Prose, a great bookstore here in Washington, and a gentleman stood up and essentially said: “I’ve worked my heart out for Abigail Spanberger, even though I know I’m well to her left.” Spanberger needed the active support of such progressives. And in 2020, those two sides will need to come together again. I’d love to see a rally somewhere with Spanberger and Pressley and various different parts of the Democratic coalition talking about how they all need to work together.

Sure, and before readers get over-enthused about 2018’s (relatively predictable) midterm swing in political momentum, and with the specters of post-1982 Democratic or post-2010 Republican optimism in mind, could you sketch some pivotal challenges of now maintaining, coordinating, broadening, and further energizing this emergent majority? How might stitching together a diversified Congressional tapestry, for example, differ from molding a more monolithic presidential electorate?

That’s quite right. We have to keep in mind that while midterm swings sometimes do predict what will happen next (2006 provides a positive example), impressive midterm results like 1982 and 2010 did not foreshadow the next national elections. One beautiful part of Congressional campaigns comes from your party really running 435 candidates, for 435 different electorates. You can run an Abigail Spanberger or a Mikie Sherrill in more moderate districts, and you can run an AOC or Ayanna Pressley in more progressive districts. That doesn’t work in a presidential race. The Whigs actually tried to run four different presidential candidates in 1836, to appeal to different parts of the country. This didn’t get them very far. And even just the binary choice that Democrats now face between Bernie and Biden will produce an awful lot of static in the party. So can both of these campaigns send a signal to Democrats on all sides that we ultimately need to work together, as interdependent parts of the same party?

Jane Kleeb, the chair of Nebraska’s Democratic Party, comes out of the Bernie movement. But she insists quite convincingly that the party has to stay open to “many shades of blue.” Biden has two big and well-recognized advantages in this election, based on the trust he has built so far among African American voters (particularly older voters), and on his ability to reach out and persuade white working-class voters. Biden has a core weakness in how little he has so far appealed to younger voters. Bernie has done an excellent job building enthusiasm among progressives, but I worry about some of the language he uses in writing off the entire moderate wing of the party, as some well-organized “establishment.” I worry about this because Bernie couldn’t win the election without winning over more of those moderate voters — and because, if Bernie loses the nomination, Biden needs Bernie’s voters.

If this book contributes in any way to 2020, I hope it shows politicians and activists that you can’t stake out some extreme moralizing position against the other side of your own party. Moderates cannot look at progressives as impractical idealists blowing this election. The left can’t look at moderates as a bunch of neoliberal sellouts. If we treat each other that way in the remaining primaries, we’ll have a whole lot of trouble defeating Donald Trump. Here I tend to quote my favorite theologian, Reinhold Niebuhr, who said we must look for “the truth in our opponents’ error and the error in our own truth.” I’m pleading with moderates and progressives alike to do this.

For an added historical dimension here, I appreciate your accounts of New Deal-era and Civil Rights-era coalition dynamics in which a mobilized left figured out how to put significant pressure on establishment Democrat leaders without undermining those leaders. By extension, what might it look like today for progressives to gain increasing power and prestige within the Democratic Party, even while helping moderates to win our national elections?

Richard Nixon used to say: “I’m glad you asked that question,” particularly when he wasn’t glad [Laughter]. But in this case I’m truly glad you asked, because I do sense that we’ve lacked a functional relationship between the left and what you might call the broad liberal or Democratic center, ever since the Vietnam era. The Vietnam War busted a pretty functional and longstanding relationship. In the book, I go out of my way to clarify why the left had ample cause to feel frustrated and even betrayed by a liberal establishment leading the country into the Vietnam escalation. Nonetheless, the loss of that functional relationship really set us back.

Again, Code Red makes a special point of shouting out Sidney Hillman and the CIO (the Congress of International Organizations, the left-leaning side of the 1930s labor movement) for simultaneously giving Franklin Roosevelt critical support against conservative opponents, but also pushing Roosevelt in a more progressive direction. I cite the famous quote attributed to Roosevelt (though still disputed) where he told interlocutors from his left: “I agree with you. Now go make me do it.” Popular mobilization definitely can help a center-left political leader move in the more progressive direction that this person often in fact wants to move in.

The Civil Rights era provides another classic example. JFK came to civil rights slowly. Martin Luther King Jr. (who, I should note, since I do have inclinations toward gradualism, famously criticized “the tranquilizing drug of gradualism”) masterfully directed nonviolent public actions, and developed powerful arguments like his “Letter from Birmingham Jail” — really pushing a center-left establishment to take long-overdue action on civil rights. I do think we need that kind of foundational push again, say by bringing single-payer healthcare options into the broader political debate as a basic bargaining position. You never buy a house, for example (at least outside of San Francisco or Los Angeles), by offering the asking price. So progressives get understandably frustrated when moderates begin their negotiations with the asking price, and then move backwards. AOC recently made a similar point by wondering aloud something like: “If we ultimately end up with the public option, would that be so bad?”

Here I also appreciate your basic litmus test for determining whether a moderate/progressive coalition is working fruitfully, based on whether comparatively modest reforms carry forward enough momentum to result in fundamental change further down the road. How might the longer-term trajectory of Obamacare end up exemplifying this litmus test in our own time?

Back in the 1960s, left-wing writer André Gorz developed the interesting idea of “non-reformist reforms.” My politics don’t tend as far left as Gorz’s, but I’ve always appreciated his extraordinary insight that certain reforms can take on momentum so that there’s no going back — not because you repeal the democratic system and repress dissent, but because these reforms democratize certain power structures, and become so popular that no resistance from the right can succeed. When George W. Bush backed off on his efforts to privatize Social Security, for example, one main reason came from Republicans in Congress saying: “We can’t sell this in our own districts.” Social Security had become a kind of non-reformist reform. So I do consider it valuable for progressives to ask themselves: “Would this incremental change help us to achieve broader reforms we need over the long run?” The scholar Paul Starr writes about this durability of certain reforms in his important recent book Entrenchment.

Going forward, if a right-wing Supreme Court does not amend and erode Obamacare, then I think we’ll see that Obamacare really has created something sturdy to build on. Take the 2019 election for Kentucky governor. A 2020 Democratic presidential candidate might have little chance of carrying Kentucky. But the Democrats won the Kentucky governorship partly because rural pro-Trump counties opposed getting rid of the Medicaid expansion — because they knew how important that expansion had become both to individuals within their community, and to the healthcare systems where they live. And by adding a public option now as the next step at the federal level, I believe we could establish a shared and pretty much irreversible sense that everybody has a right to decent, accessible, affordable healthcare.

More broadly then, what concrete role can a sustained emphasis on economic dignity play today — perhaps particularly in terms of Democrats balancing their celebration of cultural diversity and their call for constructive citizenship? How might this focus on economic dignity speak to concerns of identity and of recognition, even while pushing for a proactively predistributive/redistributive policy agenda designed to foster sustainable prosperity for all? And again, how might this broader appeal to honor and respect, these recalibrated “family values,” provide the catalyzing moral frame for a wide range of egalitarian reforms?

Well, I mentioned earlier Sherrod Brown’s call for the dignity of work, and in this book I want to establish dignity as a core proposition all by itself. Over the past couple weeks of the campaign, for example, I’ve noticed an awful lot of talk about restoring dignity to the White House. If you want to critique Donald Trump’s behavior, while also moving beyond his distracting antics, it seems useful to talk about restoring dignity. On economic dignity, I also want to shout out Gene Sperling, whom I quote at some length, and who has a forthcoming book on economic dignity, which I hope will get a wide readership. Gene lays out three basic propositions connected to economic dignity: “the capacity to care for family and experience its joys,” the “pursuit of potential and purpose,” and “economic participation without domination or humiliation.” I really love that Gene puts family first. I speak a lot in this book about the need to shift the phrase “family values” away from bigoted attacks on LGBTQ people, and towards an economic system that truly honors the work that parents do: with better family-leave laws, with far better child-care provisions and support, and with an economic market that actually rewards parenting — as an essential component of a functional and prosperous society.

Similarly, in terms of both economic and social dignity, and Gene’s call for “the pursuit of potential and purpose,” I think we need a much sharper focus on addressing all of the anger out there right now across our lines of racial division, and in younger generations hit so hard by the 2008 crash’s aftermath. According to the data, social mobility has significantly diminished within the United States, and compared to many social-democratic capitalist nations. And as for “economic participation without domination or humiliation,” my book shouts out Elizabeth Warren’s proposal for a bill of rights for gig-economy workers, who need more control over their schedules, more predictability in their income, more power at work — which some of the better employers (but not nearly enough) have begun to offer.

Another thinker crucial to my own book’s argument, particularly on questions of building multiracial coalitions, is William Julius Wilson. In his 1996 book When Work Disappears, Wilson discusses the devastating impact of deindustrialization, and the disappearance of well-paying blue-collar work, on inner cities all across our country at that time. And today we can see the very same forces Wilson described so accurately and so effectively, now hitting all kinds of American communities, many of them with large white working-class populations, places such as Reading and Erie in Pennsylvania, or Youngstown in Ohio. I consider it essential for Democrats and progressives and really all Americans to recognize that African Americans have faced distinct and more severe burdens than the rest of us — and also that, nonetheless, workers of all races have an interest in fighting together for their shared economic advancement.

So Code Red looks back to Robert Kennedy’s 1968 campaign, which tapped this idea of equal dignity so powerfully to appeal both to white working-class people and to African Americans — all during another period of intense racial division. I also point to the official title of the main 1963 Civil Rights march, “The March on Washington For Jobs and Freedom.” “Jobs” came first because, to exercise your rights, you first need the economic wherewithal to do so. King and the early Civil Rights movement understood that. And by the way, so did the United Auto Workers, which supported that great march on Washington. Today we need to look back at those kinds of politics, in part to see our way forward to an updated version of that alliance.

Similarly, alongside reinventing family values, what might it look like to redirect certain social energies now claimed by populist nationalism towards a revised mode of “inclusive patriotism” — with national sovereignty perhaps still an essential component of social-democratic policy frameworks, or of distributed worldwide prosperity, or rule of law, or justice, or environmental stewardship? What role can foreign-policy discussions play in fusing together not just a coalition of traditional internationalists and impassioned activists, but also a broader American electorate recommitted to the US taking on a robust global portfolio, and relieved to see our distinct global stature once again operating on behalf of ordinary citizens’ well-being?

For Brexit, one of the most effective (if in many ways dishonest) slogans was: “Take back control.” And nationalism’s rise does, in part, reflect a backlash against immigration from non-white countries. But it is also reflects the sense among a significant number of working-class voters (in the UK, the US, and elsewhere) that they have less control now over their lives and their political systems. So here I prefer to talk about how patriotism (which has less overtly xenophobic or authoritarian overtones than “nationalism”), how an honest love of country, need not imply a profound chauvinism — any more than the specific love for your own family implies your separation from other families. In fact, you can argue that a love for one’s own family breeds love for other families, for a shared community, for country. So I believe strongly that progressives shouldn’t back away from embracing patriotism. More broadly, as Yascha Mounk, William Galston, and John Judis have pointed out in different ways, patriotism can foster the very solidarity that we need to build a more egalitarian society in which we all look out for each other.

So again, on one hand, Joe Biden’s liberal internationalism feels quite appropriate to our time. It acknowledges that we cannot and should not go on fighting endless wars, but it still asserts a distinct role for the US to play, and recognizes the dangers (if the US simply retreats) of our world becoming less democratic, less open, less ready to act on climate, less supportive of human rights and women’s rights. I doubt many of us really want a world where America abdicates these roles, and China and Russia and any number of autocratic regimes step in to fill the vacuum. Again, this doesn’t mean denying the longstanding legacy of the US often not living up to its own democratic rhetoric. Both Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders have offered powerful interventions in articles and speeches, arguing that a progressive foreign policy cannot simply pursue abstract ideals and geopolitical strategies, but must stand up for the specific interests of our own Main Streets — and by extension, for workers around the world.

We need to marry liberal internationalism with that Sanders and Warren critique. Liberal internationalists, and global activists on health, climate, and human-rights issues, will not rally broad public support unless the average American sees our foreign policy as embedded in this idea of standing up for the average citizen. The 20th-century architects of our liberal international order, such as Franklin Roosevelt and Harry Truman, self-consciously presented themselves to working Americans as not just pursuing global justice, but as protecting the American dream. Of course they failed to extend this vision of social democracy to the whole world in equal ways. But they did actively promote a social-democratic bargain designed to produce more just and more stable and more prosperous economies across Western Europe. Post-FDR officials did this for practical reasons in their fight against communism, but they also believed in that social-democratic bargain.

Finally then, along related lines, where do you see (and where would you like to see) effective efforts to bring into the fold (or at least to engage) pragmatic moderates who previously would have fit into a more responsible GOP? Who among that group could feel more affinity to a reform-minded left-leaning coalition than to today’s radicalized and rule-of-law-flouting conservatives?

I’ll close, as I usually do in giving talks about this book, by citing one of my favorite quotations, from the veteran political commentator Mark Shields. Shields says that in politics, as in religion, you can either hunt for heretics or search for converts. If there was ever a moment when the search for converts should, as it were, trump the hunt for heretics (both within center-left coalitions, and really across the political spectrum), we’ve reached that moment right now. It’s the way we’ll demonstrate anew our nation’s capacity for self-correction, social reconstruction, and democratic self-government.