Beginning with its foreword by Jonathan Gold, This Is (Not) L.A. celebrates Los Angeles’s diversity and quality of life while unraveling the most prevalent clichés about the city. Divided into visually dynamic chapters based on myths about the city — from LA Has No Seasons to LA Is Full of Freaks and Flakes — the book focuses on the great things about the city and its residents. I spoke with Jen Bilik, author of the book with Kate Sullivan, and founder of Knock Knock, a book and gifts company based on LA’s Westside, by email.

¤

DAVID SHOOK: One of the ideas that emerges in both Jonathan Gold’s foreword and your introduction to This Is (Not) L.A. is that Los Angeles is a city of reinvention, a city in a constant state of mutation, and that because of that it’s also a city that anyone can claim as their own. You’re from the Bay Area. What made you decide that Los Angeles was home, and what specific things about the city made you fall in love with it to the degree that you wrote a book to defend it and debunk the many clichés that the rest of the country believes about us?

JEN BILIK: If you had told the younger me that I would one day live in Los Angeles, let alone love it and stay for 20 years running, I would have scoffed. The Los Angeles of my childhood — through the eyes of my grandparents, who lived in Sylmar — and the Los Angeles of reputation, vastly negative in both the Bay Area’s and New York’s estimations, put me firmly in the category of LA hater. And like many transplant Angelenos, I moved here without thinking it would be permanent or long lasting. I left myself an out (by way of my sublet NYC apartment).

The turning point was helping to create a book showcasing Hollywood from the vantage point of the Chateau Marmont Hotel. As the book’s editor, I was tasked with identifying Hollywood historians and image archives, tellers of stories and troves of research. One historian in particular, Laurie Jacobson, started driving me around the Hollywood Hills and narrating the many layers of pasts that had been painted over just one hundred years (at that point, I didn’t know anything about LA’s pre-European timeline). We drove up little streets and curved around steep hills, something noteworthy at every turn.

I knew I wanted to leave New York City. I wasn’t sure if it was permanent. My motivation was that it was time for me to do my own thing. I didn’t yet know what that thing was, but I did know that New York was too noisy in every way — to the ears, eyes, body, and soul. Visiting Los Angeles, I felt a refreshing blankness and space — in a car, not on a subway, long streets to the ocean, the beach’s horizon line. I felt I would be able to hear myself think in Los Angeles.

In the end, it was between moving back to the Bay Area of my childhood or to a new Los Angeles. The Bay Area felt regressive and stagnantly smug in its lifestyle, less driven, with nothing to rebel against (this was before the rise of tech). Los Angeles had an underbelly, currents of energy that drove ambition. I wanted that energy. I wasn’t yet ready to sink into a life defined by its comforts.

As Los Angeles unfurled itself to me, I began to think it was a well-kept secret — but with a population in the millions, it wasn’t a secret at all; with my blinders on, I hadn’t seen it. At the same time, LA had evolved quite a bit since the 1970s and 1980s. I’d argue that the LA of the late 1990s had far more cohesiveness and vibrancy than the decades before it. So, it wasn’t just my experience of LA that had changed — LA had changed, too.

There are so many things I love about Los Angeles. I love the driven, ambitious, smart people I’m lucky enough to know here, in diverse fields and with varying points of view. I love the cultural mosaic, driving from Koreatown to Little Ethiopia to Japanese Sawtelle. I love the access to nature, the hundreds of thousands of acres of parks and hiking, the Santa Monica Mountains in our backyard and the beach in the front. I love the history and the stories, the sense of people living on this land since the end of the Ice Age, some 13,000 years ago. I love that LA looks one way from the outside and an entirely other way from within. And, despite my resistance to giving in to the Bay Area’s emphasis on quality of life, it turns out that Los Angeles can offer quite a lovely quality of life, especially in Venice during the first 15 years of the 2000s, before it turned into a weird blend of Disneyland and Mad Max, where I had found my Berkeley-esque home.

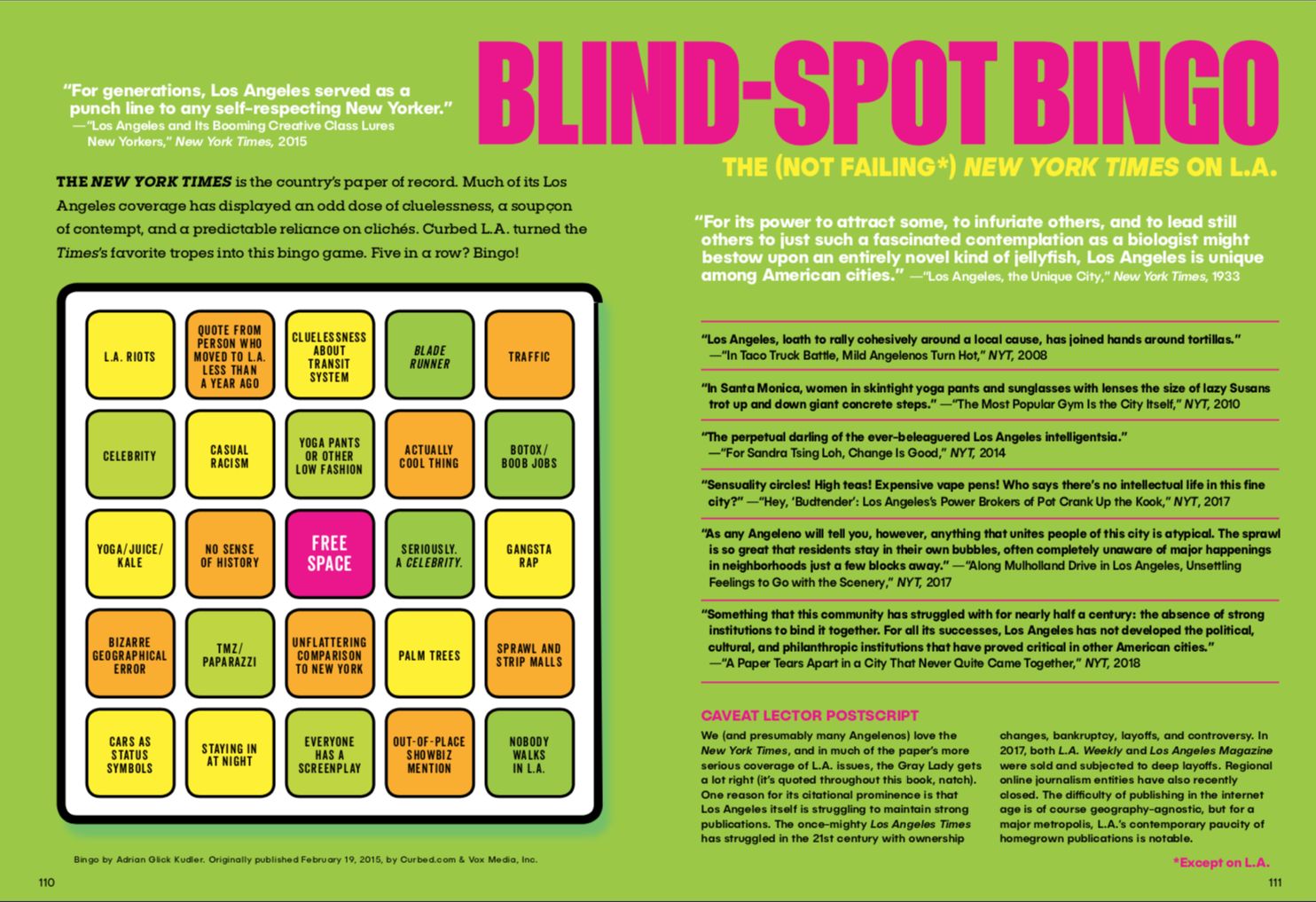

I became an informal defender of Los Angeles, with plenty of New Yorkers and Northern Californians to argue against. But there was a moment when I realized how systemic, reflexive, and unaware was the disparagement of LA — my friend Alissa Walker started writing blog posts ranking periodicals of record, the New York Times, the New Yorker, Vanity Fair, for how many LA clichés and tired tropes they used. Somehow that was the impetus for awakening me to question why we accepted this reputation, why we had internalized others’ view of us so that we disparaged ourselves before anybody else could. The myth-busting was ON.

I think it’s true that Angelenos are allowed to make fun of the city and its people, or even to complain about certain things that we would balk at an outsider critiquing. I think that it’s also true — as you debunk in the myth “LA Has an Inferiority Complex” — that we don’t care too much about what other people think. There’s a great spread in the book called “We Can Take a Joke,” which features 30-odd quotes poking fun at Los Angeles, beginning with the Will Rogers classic, “Tilt this country on end and everything loose will slide into Los Angeles.” What jokes or critiques leveled at Los Angeles do you think are true? Do you have any of your own?

It’s a defining feature of comedy that all jokes have some basis in reality — otherwise they wouldn’t be funny. All places have their clichés and stereotypes, but LA’s have somehow been swallowed as fact. You’ve made a really good point that we don’t have an inferiority complex yet we’re quick to make the joke on ourselves — I do believe we’ve internalized others’ views of us, part of my motivation for writing the book. Stand proud, Angelenos!

While I don’t put much truck by the jokes we feature in our “We Can Take a Joke” spread (with Angelyne illustrating the background, I might add), I do love the Instagram feed @OverheardLA, which somehow gets the irritations and truisms of LA life just right — but when viewed from the outside, they seem to be confirmations of reputation, and when viewed from the inside, it’s more like, “Those are our more extreme people and aren’t they funny?” We study abnormal psychology to understand “normal” psychology. Exaggerated features help us to grok reality. Food and fitness are clichés that apply — avocados everywhere, gluten-free everybody, “I slept through my trainer after partying all night,” etc. What the rest of the country seems to deny about that, however, is that LA trends become national trends. It starts out making fun of Angelenos, and it ends up applying to the whole country. I mean, please: LA didn’t cause the Great Avocado Shortage of 2017 — it was the rest of the country getting on our toast bandwagon.

Your new book presents a massive amount of information without seeming overwhelming. In my opinion, that’s largely for two reasons: the book’s striking visual design, beginning with its horizontal orientation, and its good-natured sense of humor. Were those elements of the book’s character strategic decisions you made before embarking on the project, or did they emerge naturally from your good eye and wit?

I can’t say that I would deny anyone who says something might have emerged naturally from my good eye and wit (can you add “stunning good looks” to that?), but yes, it’s totally strategic. When I started my publishing and gift company, Knock Knock, in 2002, one of my motivations was to write and design at the same time. I wanted words and visuals to develop simultaneously, not one smushed in to fit the other. I had been an editor of coffee table books through the mid-1990s advent of desktop publishing, right on time to observe what I characterize as the “USA Today pie-chart and sidebar revolution.” Shifting publication layouts from paste-up boards to software allowed for far more improvisational freedom of information, and over time, it’s evolved into the way we process information. Of course, the internet took it even further. I characterize it as people wanting their information “predigested.” It’s sliced and diced so that it can be entered in any direction — read front to back or just glimpsed here and there in the bathroom.

I passionately believe that things don’t have to look serious to be serious, that substantive information can be published in non-book — or in decorative book — forms. One challenge there, however, is the age-old coffee table editor’s woe: people don’t read coffee table books. We labor tremendously over the text, and nobody reads it. As a longtime coffee table book editor, I don’t even read coffee table books (but they sure do look good on my coffee table).

With This Is (Not) L.A., we wanted to strike the balance between attractive looks, approachable segmentation of information (The Myth, The Reality, Reality Check #2, Final Mindblower, etc.), and seduction to read. We want people to read this book, and if it’s too pretty, they often won’t. Therefore the segmentation of information is key — readers will enter the book because it looks easy, but hopefully then they’ll be hooked to read more. It’s this odd balance between what we want a book to look like (all of them should look amazing!) and how we might get people actually to read the thing.

But it’s all intentional, for sure. Including the apples-to-apples orientation of slicing and dicing each of the eighteen myths in the same way. The reader is trained on the structure of the book as they go, and I believe that leads to more inclination to read because it feels comforting and snappy rather than daunting.

Los Angeles has a rich literary history, as home to exiled writers like Brecht and Mann, consular officials like Nobel laureate Gabriela Mistral and Vinícius de Moraes, and scores of American writers, native and adopted Angelenos alike. Who are some of your favorite LA authors, and what are some of your favorite LA books?

Sadly, I have had much less time to read LA fiction over the last, well, 16 years, than I would like. I went through a long James M. Cain phase, especially The Postman Always Rings Twice and Mildred Pierce. Oh, how I love Mildred Pierce. William Faulkner wrote a short story, “Golden Land,” which is just about one of the best pieces of LA fiction I’ve ever read. The French writer Blaise Cendrars was sent by the newspaper Paris-Soir for two weeks in 1936 to report on Hollywood, and his book-length account is remarkably charming — although already the myth that nobody walks in LA was well entrenched: “In Hollywood,” Cendrars reported, “anyone who walks around on foot is a suspect.” What Makes Sammy Run, by Budd Schulberg, and Picture, by Lillian Ross, are depiction-of-Hollywood favorites.

The great California historian Kevin Starr characterized the European writers and filmmakers who came (mostly reluctantly) to Los Angeles around World War II as “The most complete migration of artists and intellectuals in European history.” Unfortunately, they were also the source for early LA enmity, as they really longed to be back in Europe — or at the very least, New York. Longtime New Yorker writer S. N. Behrman notes in his memoir, “With the influx of the refugees in the 1930s Hollywood became a kind of Athens. It was as crowded with artists as Renaissance Florence. It was a Golden Era. It had never happened before. It will never happen again.”

There’s so much good stuff. I want to take a year off just to read some of it!

I’m especially fond of Brecht’s “Hollywood Elegies,” which I think poke the kind of fun that we’ve discussed. Here, the first quatrain, in Adam Kirsch’s recent translation, one of several versions I admire:

Under the long green hair of pepper trees,

The writers and composers work the street.

Bach’s new score is crumpled in his pocket,

Dante sways his ass-cheeks to the beat.

That’s fantastic, and totally characterizes the legendary LA struggle between high art (Bach and Dante) and film work (working the street). I believe they have met much more often than people credit — I mean, John Williams? Some of the great painterly filmmakers? For how long must we continue to hold on to pre–twentieth century conceptions of “high art” and what constitutes a city?

Could you have started Knock Knock anywhere besides Los Angeles? How does the publishing company’s character reflect its home city?

I do think I could have started Knock Knock elsewhere, but it would have been a different company, an alternate parallel reality that would be impossible to characterize theoretically. Sometimes I compare Knock Knock’s experience in assembling a team to that of Chronicle Books, in San Francisco. For a long time, it seemed they had an easier go of finding designers and editors. In some ways, being in L.A. has worked against us in that regard — except when we do find people on our wavelength, they are a great fit and groove for us, and for them. We’ve found over the years that creative professionals from other LA industries, whether comedy, TV writing, or advertising, don’t necessarily fit with what we do.

Knock Knock reflects Los Angeles, however, in its rejection of norms, in its ability to tip sacred cows, and probably in my own sense of freedom in moving here to explore what “my thing” might be. Los Angeles is certainly inextricable from Los Angeles, but I don’t always know quite how. It just feels that way.

What is the future of Los Angeles?

One thing is for sure: I feel much more optimistic about the future of Los Angeles than I do about the future of the country. We currently find ourselves at such a scary, weird point in our nation and values, totally unpredictable in where it will go. California has risen as a phenomenal counterpoint to what’s going on in the government right now (and the people who elected them). Pioneering progressive change has long been one of California’s roles. The Clean Air Act of 1970 arose out of LA’s formerly notorious smog and led to auto-emissions standards that, because California is the country’s largest car market, were almost universally adopted. There are so many amazing things going on in LA right now, many championed by Mayor Eric Garcetti, in public transportation, biking and walking, restoring the LA river, supporting entrepreneurship, and most important of all, fingers crossed, leading the way in addressing the shameful problem of homelessness. The city is evolving in very positive ways.

I love the future of Los Angeles that’s reflected in our multicultural population and its immigrants. We are the future — the mosaic of cultures that might remain separate in first generation but that come together subsequently. I truly believe that the future of Los Angeles, and California, is to function as both our country’s conscience and its lodestar (which will make people think that Mike Pence wrote this) in terms of race, culture, and demographics.

The future of Los Angeles rocks.