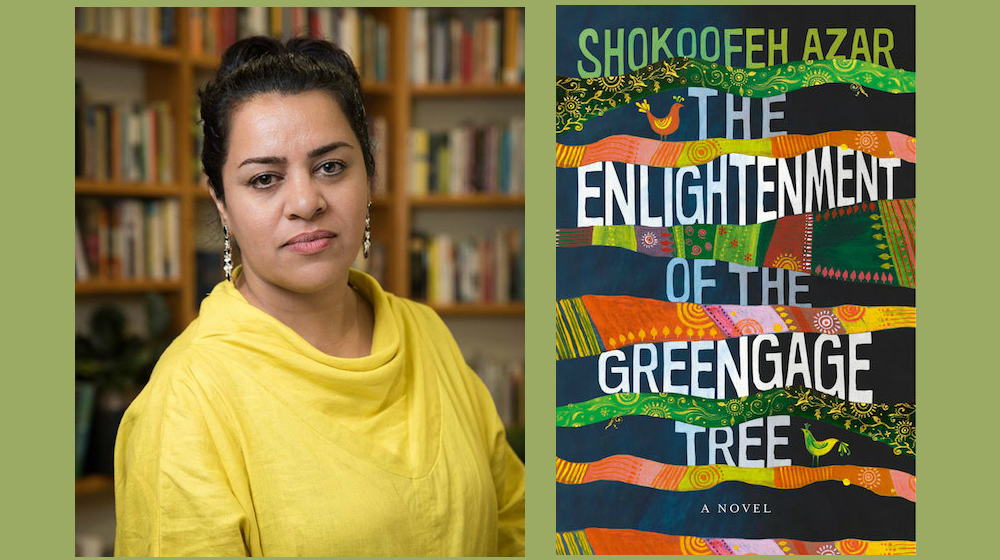

Shokoofeh Azar is interested in family, love, myth, belonging, and belief. Born in Iran, Azar now lives outside Melbourne, Australia. Her book The Enlightenment of the Greengage Tree was shortlisted for the 2018 Stella Prize, the premier national prize for women writers. Europa Editions will publish the book in North America in Fall 2019.

¤

ROBERT WOOD: Can you tell us about your early reading life? What stories were you drawn to as a child and what books left a lasting impact on you?

SHOKOOFEH AZAR: When I was a child, books were everywhere in our house and each of us had his or her own library. My father’s prized possessions were books. He had great taste in books; he knew great writers, poets, illustrators, translators, and publishers. He had a good reason for purchasing every single book. He purchased books because of the illustrator, author, poet, or even the translator of the book. For me, the message was that the book was important.

I remember when I was six or seven I read a book about racism in the US. But, the other books that I remember from my childhood library are: Gilgamesh (a myth from Mesopotamia), Stories from Shah Nameh (classic Persian epic), Family Under the Bridge (Natalie Savage Carlson), Pippi Longstocking (Astrid Lindgren), The Little Prince (Antoine de Saint-Exupéry) and many other Iranian children’s poems and storybooks that my father chose very carefully for us to read. All of those books had a deep impact on me. I remember them one by one and I kept them. And it is very interesting because I still read in the same category; literature, mythology, philosophy, and Persian classics. But, the first character that truly impacted on me was Pippi. She was my childhood hero. I wanted to be like her: brave, adventurous, and a person who doesn’t care about the norms of the community. She is a norm-breaker.

Being a norm-breaker certainly comes up in your writing and throughout your life journey. You began your career as a journalist. Why did you become a journalist?

When I decided to shift from being a literary encyclopedia writer and editor to a journalist, Iran was going through a turbulent period. The murder of the intellectuals, known as “chain killings” by the Iranian Ministry of Intelligence, had just begun. And one day my father, in his publishing office, showed me a long list that included his name. Unknown people disclosed the list and there were about 90 names on there. Fortunately, my father’s name was at the bottom, but the top of the list had names of all those intellectuals who had already been killed. One of his friends in the Culture and Guidance Ministry had given that list to my father in secret.

It was about 20 years ago, in the early days of the Reform Movement, and I kept track of the news in left-wing newspapers. Every day, we had passionate arguments and discussions about Iran’s political and social issues with my colleagues at the office. One day a colleague told me: “Shokoofeh, working as a literary researcher is not enough for you. You must be a journalist.” And I thought: “Wow, this is an exciting idea.” Almost at the same time, another colleague informed me that a very well-known left-wing newspaper, which we read and followed every day, needed a tech editor. A tech editor in the newspaper is a person who watches the text for the language. It actually was a lower level job compared to what I was doing but I had a plan. I immediately applied and was accepted. I worked as a tech editor for six months or less. One day when I was still in tech editing office, I wrote my first article for the same newspaper about “What is the social commitment and responsibility of literature?” I sent it to the editorial office via a literary journalist. As a tech editor, we were not allowed to go to the editorial office, where all the journalists sat, talked, smoked, and wrote their stories. And I was dying to go there, to be one of them. The next day, the sub-editor came to our office to show me my article in the newspaper’s literary page, and told me: “Why you don’t write more?” So, I wrote more.

I am glad you wrote more. Tell us about your recent writing, The Enlightenment of the Greengage Tree.

The Enlightenment of the Greengage Tree is a literary novel set in Iran in the period immediately after the Islamic Revolution in 1979. Using the lyrical magic realism style of classical Persian storytelling, I tried to draw the reader deep into the heart of a family of five, caught in the maelstrom of post-revolutionary chaos and brutality that sweeps across our ancient land and its people. The story starts in Tehran in the heart of the revolution and continues into the jungle of northern Iran, where the family tries to find peace and safety but nothing goes as they had planned.

The Enlightenment of the Greengage Tree is an embodiment of Iranian life in constant oscillation, struggle and play between four opposing poles: life and death, politics and religion. The sorrow residing in the depths of our joy is the product of a life between these four poles. In a way you could say The Enlightenment of the Greengage Tree is about the tragedy of Iranian life today. This tragedy is not in our deaths but in our lives. Our lives are rooted in despair, compulsion and the death of dreams. I believe the tragedy of the current age is not in the glorious end to a glorious life. Our tragedy lies in our paltry lives and futile deaths, like the wavering shadow of a tree that castes a momentary, ephemeral scene on a wall under the sun and then disappears. I wanted to record these moments before they disappear forever from our history.

This novel was written in two and a half years, while everyone was asleep at home. It was a novel of midnight. Writing this novel was like hard psychotherapy sessions for me. Like in a period of serious psychotherapy, the psychotherapists destroy your mental personality to rebuild it in the best possible way, I struggled with my deep self-censorship and deep tides in myself. I was destroyed, and rebuilt myself and my story. I experienced a depth of emotion. I cried, was angry, astonished, perplexed, and laughed in process of writing this book.

You certainly get a sense that the book is a great journey. It moves places and it moves us as readers, in an emotional and intellectual sense. One thing that readers may notice is that there are layers of Persian storytelling as well as overtures to classics of world literature including those from Gabriel García Márquez, Salman Rushdie, and Angela Carter. Can you speak about magical realism’s influence on your voice?

Unfortunately, I’ve never read any books by Angela Carter (none of her books is translated into Farsi) or Salman Rushdie. Due to Khomeini’s famous fatwa on Rushdie’s book Satanic Verses, his books are forbidden in Iran. But, I read from most magic realist authors such as Gabriel Garía Márquez, Jorge Luis Borges, Carlos Fuentes, Miguel Ángel Asturias, Toni Morrison, Haruki Murakami, Kenzaburo Oe and a very important magic realism writer, Mircea Eliade. He is great Romanian Mythologist. Mircea Eliade has many books in mythology and only a few in fiction. His most important novel, titled On Mantuleasa Street, is a fascinating magical realism novel which is like my holy book, after One Hundred Years of Solitude by Márquez.

Magical realism comes from an old or ancient deep-seated insight. It is more than a literary style that you can learn at university or from the books. I did not learn it only by reading magic realism modern fictions, but I also learned from mythic texts, Persian classic texts, and my own people’s culture. People of old or ancient cultures sometimes seek the metaphysical solution for realistic problems. And it has nothing to do with superstition or religion. If you learn to look at these beliefs in the right way and deeply, you can find the roots of myths, and important and beautiful meanings in these beliefs.

For example, in some villages in Iran, people get together and sing, pray, and cry asking the sky to rain when there is no rain for a long time. And sometimes it really rains. Or, in the other village one day in spring, women drive all the men out of the village and they take all responsibilities of the village, which in fact, it is nothing except dancing, singing, laughing, and eating. People believe that this will bring blessings and luck to the village for the whole of next year. Therefore, most people in Iran live in the heart of magical and supernatural beliefs. In my opinion, it is part of the beauty of ancient cultures such as Iran, India, and Egypt.

The example you cite above about women taking over the village resonates with the book, which inflects the classics and myths and beliefs in a proudly feminist way. There are sympathetic portrayals of strong women characters and a disposition that embraces conversations about gender. This is to say nothing of how it has been read by the Australian literary establishment, including nomination for The Stella Prize, a women’s only prize. Can you speak about the women of The Enlightenment of the Greengage Tree?

I am writing about the emotional history of a group of people who live inside of a political border called Iran but my audience is literature lovers. It does not matter if they are men or women and it does not matter where they live. It is a very fundamental point of view of mine as a writer. But, you are right, I mostly portray strong and different women just because I am a woman and I know this gender better.

My story’s characters are always at the stages of self-knowledge, self-correction, and they are trying to achieve their aspirations. They are active, independent, very emotional, but mentally strong. Usually, even their death is not the end of their efforts and lives. They are constantly shaping their character and the world. It is as if they are always trying to do the following words of Joseph Campbell, American mythologist: “follow your bliss.”

Even in my short stories, women and men always are self- critics maybe because, in my opinion, a person begins “maturity” when they are deeply involved with this question: who am I? This simple question can lead us to know our internal evil and goodness, our weaknesses and strengths. And through this question, we can experience the stages of flourishing and maturity. But, you can only answer this ontological question when you begin to test yourself. Women and men in my stories are not afraid to test themselves in a difficult, different, contradictory, and even dangerous situations. This is because they are looking for answers to this question. They are looking for maturity.

As a follow-up question, how does this fit with other questions of identity and belonging, in particular a question of being Iranian, of having a double-consciousness of place that now includes Australia, of how you have moved between places in real and literary terms?

You know when a knife makes a deep wound in your body, it does not feel pain for the moments. This was exactly my feeling in the first years of my arrival in Australia. I still did not feel the pain of going away from my beloved ancient land, until about two years ago, when suddenly a tear began. But, the flood of tears ended up with accepting the reality of my life. Now, I feel very comfortable in Australia and I am very happy to have the opportunity in this democratic country to write uncensored. This is the greatest blessing of the Western world.

If that is the greatest blessing for you, what will you do with it? What are you working on at the moment, and what are your future projects?

I am a student in communication/journalism now at Deakin University because journalism is an inseparable part of my life. And, at the same time I am slowly working on my second novel. Writing is a very profound process of thinking, feeling, and discovering for me and I never push myself to write faster. I don’t compete, neither with myself nor with others. But I will tell you what my second novel is about.

In my first novel I created and answered the following question: can we survive without passion and hope in a religious dictatorial system? In my second novel, with the same writing style, I am going to create and answer the question: can true love exist in a religious dictatorship in which the body and love are censored? When you are not allowed to love your body and mind, can you truly be in love with another’s body and mind?