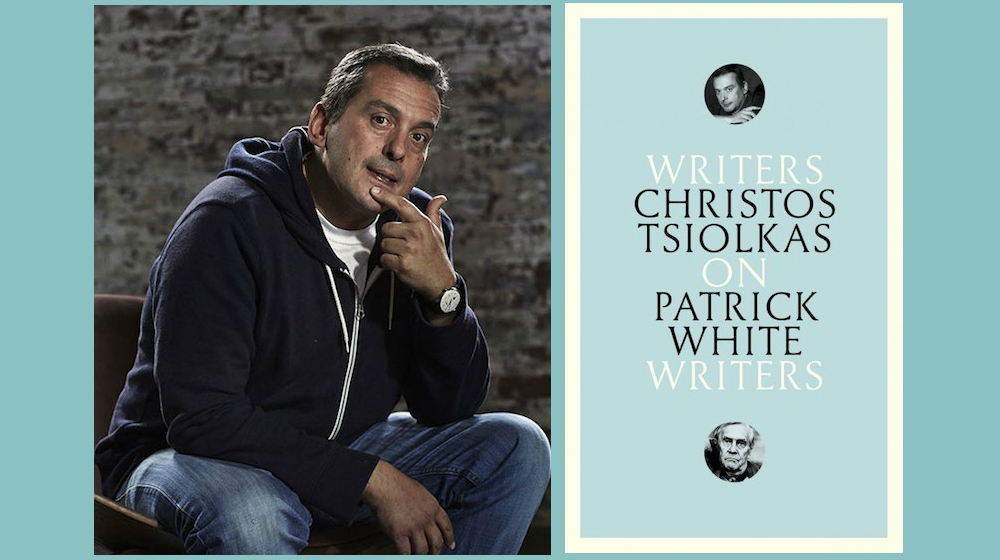

Christos Tsiolkas is an award-winning Australian writer. He is interested in identity, passion, relationships, belonging, and home. He won Overall Best Book in the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize 2009, was shortlisted for the 2009 Miles Franklin Literary Award, longlisted for the 2010 Man Booker Prize, and won the Australian Literary Society Gold Medal for his novel, The Slap. We caught up to speak about his recently released book, On Patrick White.

¤

ROBERT WOOD: Tell us about the Patrick White you knew before you wrote this book. What kind of figure was and is Patrick White to you?

CHRISTOS TSIOLKAS: For me, there have been various versions of Patrick White, each version corresponding to different periods in my own life. As an adolescent I knew him as a shadow, the one Australian writer to have won the Nobel Prize for Literature. I attempted to read Voss when I was 15 and I quickly gave it up. I was already a vociferous reader but I hadn’t learned yet to be a diligent and disciplined reader. Basically, I had yet to discover European modernism and Voss felt difficult, impenetrable.

On Patrick White is dedicated to a high school teacher, Mr. Jurislav Havir, a Czechoslovakian immigrant who loved literature and understood that I too shared that love. He slowly introduced me to the great legacy of European literature. He gave me Stendahl, Camus, Dostoevsky, he gave me the world. He also made me understood that reading was not only for pleasure, that some of the greatest joys and discoveries in fiction come from committing patiently to the novel, that great writers don’t spoon feed their readers. I read Patrick White’s The Aunt Story and The Twyborn Affair while I was an undergraduate at university and I now understood why he was such an instrumental figure. One written as a young man and one near the end of this life, they writing is like a dance in both of them, reading them makes you breathless. But I was a young and angry man, and I dismissed him as one of the “dead white males.” I chose to follow the postmodern herd and refuted the joy I had in reading those two books. I am ashamed of that now, it was such a silly and immature response. It wasn’t until I traveled that I realized my mistake. In a bookshop in Mexico City, a young man raved to me about White, was shocked that I hadn’t read more of him. He drew parallels between White’s writing and that of the great Mexican writer, Octavio Paz. I am eternally grateful to that young man. He led me back to White and also made me discover Paz. In a tavern in Athens, an elderly woman kindly berated me for my ignorance of Patrick White. “What is it about your country that makes you turn from your giants?” she asked. It is a good question, maybe it is still the hangover of colonial legacy, looking over our shoulders to what Britain or the USA are doing.

That woman, the young man in the bookshop, my teacher, Mr. Havir, they made me understand the White that I paint in my book.

White certainly is a singular figure that contains multiplicities, so that seems like an appropriate way to come to know him. And yet, as part of that, it matters what context we read him in, from a course at university to a Mexican bookshop to a tavern in Athens. In that way, your book is part of a series by Melbourne publisher Black Inc., where contemporary writers look at important figures in the Australian literary landscape. There are other volumes, on JM Coetzee and John Marsden for example. How did you come to write the book itself as a part of the series?

I knew Chris Feik, the publisher of Black Inc., and he contacted me about the project. Black Inc. is an independent publisher in Australia and they also publish a weekly newspaper, The Saturday Paper. I am a film reviewer for that publication. I also occasionally write essays for their publication, The Monthly. So, I knew about the “Writers on Writers” series and thought it was a terrific initiative. The woman in the Athenian tavern was right, we are not good at celebrating our elders in Australia. There is another great book in that series, Erik Jensen writing on Kate Jennings. Ms. Jennings has lived in New York for quite a long while now but I always declare her as one of Oz’s best writers. When Chris approached me I had already spent a year reading all of Patrick White’s fiction. A few years ago, on a particular drunken New Year’s Eve, I swore off making puritan New Year resolutions. This time, I decided, I wasn’t going to pledge to give up anything. Instead I made the vow that for that first year I would read a poem a day. The year after, my New Year’s resolution was to read a short story a day. And then one year I decided I would read all of Patrick White. Earlier that year I had been in Athens and it was there I had the conversation about White in the tavern, so the genesis of that year’s resolution was gifted to me then. So when Chris asked me which writer I wished to write on for the “Writers on Writers” series, I was ready.

I do get a sense that one needs to be ready for Patrick White, but also to write on writers. In your way of getting ready, your book is a combination of personal reflection, literary criticism, and historical research. There are lots of threads that are woven together to form the whole. How do you sum White up, in a single image, story, or moment?

White’s The Tree of Man is sublime. I don’t use that word promiscuously. I mean that White makes you understand that the wonder of transcendence can be found in the most ordinary of people, in the most humble of situations. Stan and Amy Parker are a married couple who create a world in the wilderness. They are human, with all humanity’s failings and weaknesses, but they are also, I think, heroic in how they deal with suffering. There’s a moment of enlightenment that happens to Stan Parker in the bush — it’s a flash, the luminescence quickly vanishes — but is with him for the rest of his life. The book floored me, like all great literature, it made the world around me seem more brilliant, as if I were seeing it with greater clarity. I probably was. It’s a tremendous book, one of the great spiritual works of the 20th century.

There is that evocation of spirit in your book, and, how that is central to thinking about White’s writing. There are other elements that are central, such as the pronounced, and innovative, emphasis on White’s life partner Manoly Lascaris and how he influenced White as a writer. In your telling, Manoly becomes an important historical figure in his own right.

Even as a young man, I knew that Manoly Lascaris and Patrick White were life partners. That was very significant to me as a young gay man. Whatever my youthful pretentious and naïve dismissals of White might have been, there must have been somewhere in my consciousness that understanding of them being crucial elders. As guides. That Manoly was of Greek background, like myself, was also an important reason for my fascination. What I didn’t expect to find when I returned to reading Patrick White was the undoubted influence of Orthodox Christianity in the writing. I didn’t expect to find it because literary critics in my country hadn’t referred to it. But, the fiercely personal spiritual language that I discovered in The Tree of Man, in Voss, in all of White’s novel, was familiar to me from the rituals and language of Orthodoxy, the mystical love of God’s Creation. This love and adoration of the world that God created is, I think, one of the most acute differences between Orthodox Christianity and that of Roman Catholicism; and certainly very different to Protestantism. White wasn’t Christian but he imbued the Australian landscape with that mystical love. As soon as I realized this, very early on in my reading of him, I knew that this must have come through Manoly. Through Manoly, Patrick got one of the greatest gifts a writer can receive, a way of seeing the world anew.

In that way, seeing how you see Manoly allows us to see White differently, which is as a migrant writer. White was born in England and he studied there in high school and university. That might be a basic observation, but somehow it matters too. How did you come to the conclusion about White’s migrant status, and what does it mean for national literary myths in the Australian discourse?

It might be a difficult question to answer for an American audience, in that Australia’s colonial and racial and migrant histories are very different to that of the USA. There are four historic periods to make sense of when thinking of Australia. There is a 60,000 year-old Indigenous history. This must be the starting point of making sense of my country. What was lost, stolen, destroyed when the British came but also what survived and is still part of our continent. Then there is the moment of British colonial exploitation — in all senses of that word. Included in this historic moment are those initial decades when thousands of British and Irish convicts were transported to the newly founded colonies of Australia. Then there was the creation of the federal nation state of in 1901. One of the first acts of the new Australian parliament was to legislate the White Australia Policy that from 1901 till the end of the second World War, was to aggressively define Australian culture as white and Anglo-Celtic. And then, with the election of a leftwing Labor government in 1972, the beginning of a redefinition of Australia as multi-ethnic and multicultural, as linked as much to Asia and the Pacific as it is to Europe.

I apologize for the extended political lesson but it is necessary to get to what I mean by designating White a migrant writer. In a sense, all of us who are not Indigenous are migrants. But, it is White who is the first Australian writer to understand this. Though of British heritage himself, from the moment of his meeting Manoly, one begins to see that he is drawing explicit connections in his work between an Australian identity and the identity of an exile. His work is a long and sustained song that claims the exile as the proper and most honest Australian. The story of an exile is always a migrant story. White’s work forms the bridge between an early Anglo Australia and the Australia that I grew up in as a child of immigrants, one that was indeed multiethnic, especially in Melbourne. It will seem odd, I suspect to an American reader, but when I was growing up I was not considered “white,” so pervasive was the influence of the White Australia Policy. When I read Patrick White I am reading him alongside Manoly, if that makes sense. Manoly was a Greek-speaking citizen of the Ottoman world, a world that collapsed after WWI. His whole life was conditioned by the stories, experiences and myths of exile. I believe that from his first falling in love with Manoly, White came to see Australia through his lover’s eyes as well as his own. That is why the figure of the exile is so prominent in all of White’s work, right to the very end. There are Australian books before White’s that I love, but I write in that White’s The Tree of Man is the book I want to find in Greek and give to my mother to read. Though the characters are Anglo-Saxon, I think my mother will recognize herself in Stan and Amy Parker.

That is a very acute observation — of the centrality of exile to migrancy, of migrancy to national identity, and how they connect to White. So far, we have spoken around the text, around White, and, in a way his work has been an absent centre, and, it is as if we have exiled the books. Talk to us about his writing — what is its essential appeal? And how does that matter for readers who are in the process of re-discovering White, be that through Voss or The Eye of the Storm or The Solid Mandala?

One other aspect of Orthodox Christianity that I think influenced White’s writing is an awareness of sensuality in the world. My God, flesh and heat and color and smell, they are all so very vivid in White. His writing is intricate and particular but there are moments of delirious passion in there as well. The brutal death scene in Voss. The description of a man’s hairy arms in The Eye of the Storm. The sheer audacious sculpturing of the English language across all his work. The teasing and wit of The Twyborn Affair. I can give you a thousand moments but one of the great discoveries for me, in returning to White, was finding the humanism in him.

Humanism and existentialism were dirty words when I was going through university in the 1980s. They shouldn’t have been. Till the day that my breath fails me, I will insist on defending the promise of the humanist novel: how a great work allows us to see the world through an other’s eyes. I knew this as a young reader, and it was one of the most important instructions that Mr. Havir gave me; but bloody university made me forget this truth. That humanism — questioning and sometimes despairing in his work, sometimes exultant and defiant — is what makes White a great writer.

The Solid Mandala is, for me, of all White’s novels that one that affirms the power of this promise: that we can understand one another. By all accounts White was a crotchety man, maybe sometimes ungenerous in spirit. But The Solid Mandala is one of the most generous novels I have ever read.

I agree about that generosity and the sensuality, the kind of ardent and lyrical expression of the world out there. These are threads that other critics might see in your own writing. And so, I want to ask about White’s influence on your own creative practice. In the book, you are humble before him, but has he allowed you to raise your own standards? What does it mean for your future projects?

I write in the book that when a writer reads a great novel, she is galvanized by the experience. It’s a strange phenomenon, a combination of humility and daring. I finished The Eye of the Storm, one of White’s great late works, and almost immediately, in a rush, there came to me a novel I wanted to write. The Eye of the Storm is astonishing in how it shape-shifts as it moves between the characters, how it plays with time in language and so allows the reader to comprehend the entire history of one family. I can’t dare pretend I can write a novel as good as that one yet, nevertheless, reading a work of such brilliance isn’t disempowering. It’s like taking the most amazing drug, one with no side effects, one that makes you realize again why it is you want to write. That’s what great art does. It humbles and inspires.

I think from this moment, from this immersion into Patrick White’s writing, I am going to be more alert, hopefully more sensitive, to language and to the craft of writing. And also, hopefully, he has given me courage. Patrick White never underestimated his reader, he expected the very best of you. I want to remember that every time I write.