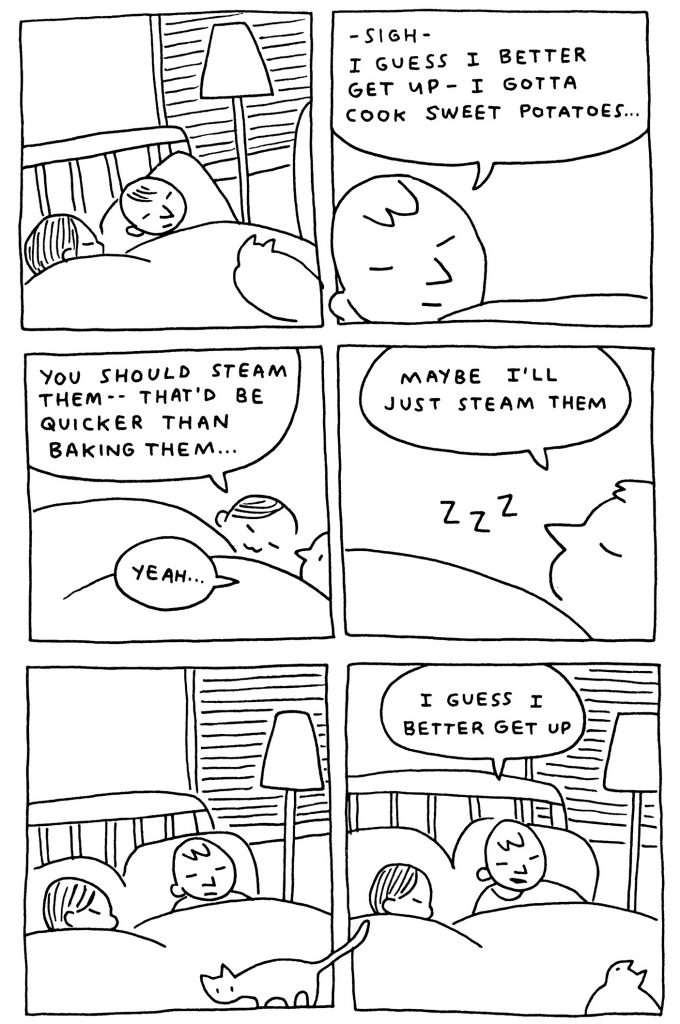

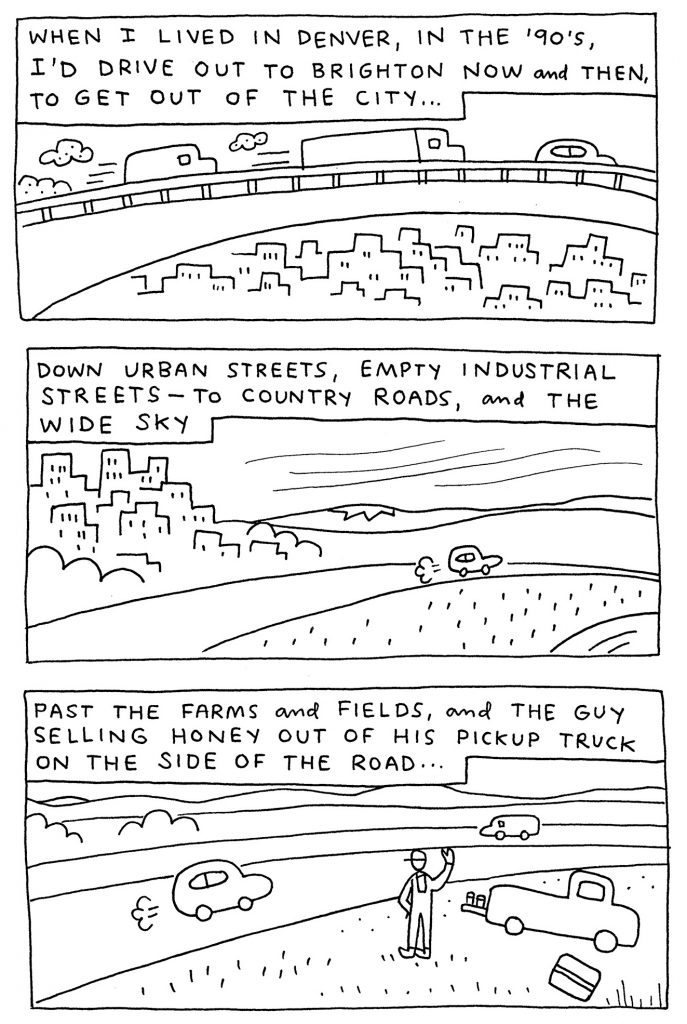

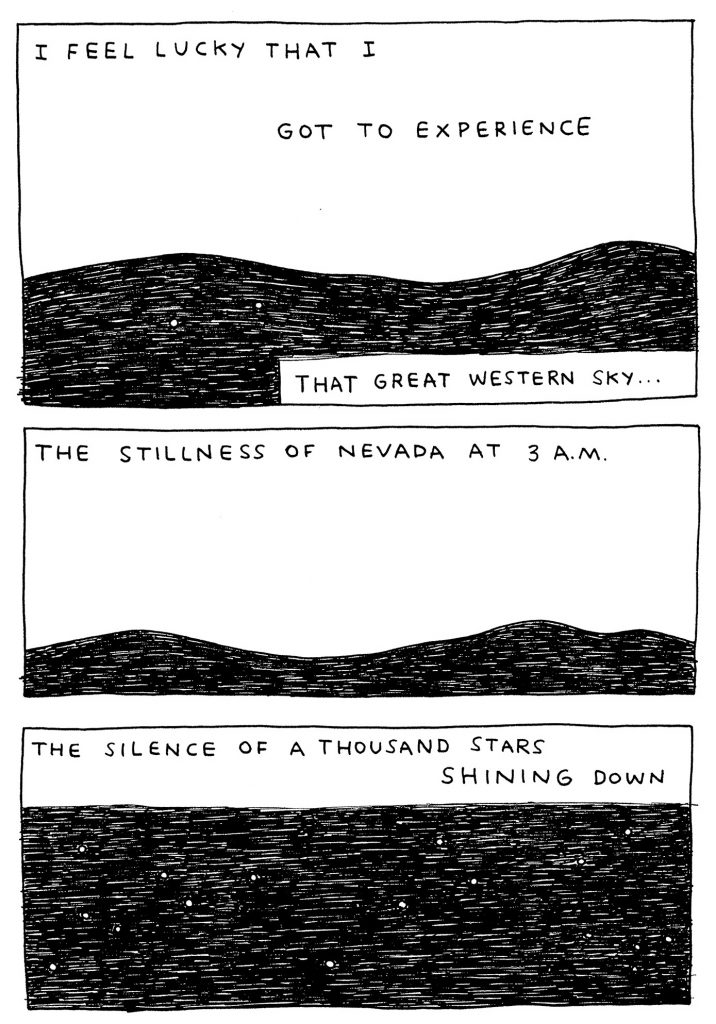

For over three decades, John Porcellino has sought out photocopiers around the country to produce King-Cat Comics, one of the longest continually published mini comics in existence. This spring, Porcellino publishes From Lone Mountain (Drawn & Quarterly), a collection of his comics about his life in Denver and San Francisco and his search for calm in each place. In his writing and drawing, Porcellino finds startling beauty in simple occasions such as waking up, getting a haircut, and being out in nature. He soulfully observes small moments and makes them grand in their effect.

Porcellino is the author of Diary of a Mosquito Abatement Man, Perfect Example, The Hospital Suite, Thoreau at Walden, 77 issues of King-Cat, and more. He is a visionary of autobiographical minimalism. I wrote to ask him about his new book and 30 years of making King-Cat.

¤

NATHAN SCOTT MCNAMARA: What inspired you to create your first zine? What were you reading at the time and what were the models for doing it?

JOHN PORCELLINO: I was a kid who was always writing and drawing. And I had an obsessive love of books. So eventually I began making my own little booklets out of typing paper and gluing the edges to make a binding. I’d draw and write in them and stack them up in my desk drawer. Then, in the early ’80s my dad got a photocopier at his office and I realized I could make copies of these little books. So I’d print up a couple and give them to my friends at school. A little while later my friends and I got into punk rock and we made what we called an “Underground Newspaper” — we were unaware of the term “zine” — at our high school, which featured sarcastic articles about our classmates and teachers, and weird comics, and little record reviews. I did this kind of stuff until 1987, when someone showed me a copy of Factsheet Five and my mind blew wide open — I realized there was a whole international network of people making little magazines like these — and I never looked back… I’d found my creative home.

I wasn’t a big comic book person growing up… I mostly read the newspaper funny pages, and James Bond novels, stuff like that. My first comics as a kid were made in emulation of monster movies on TV… drawing a series of little screens with action in them. I can’t say that when I started making zines I had any models for doing that sort of thing. I think, like a lot of people at the time, I came to self-publishing through just having a will to create, coupled with thinking creatively about photocopiers.

When you first started publishing King-Cat in 1989, you say you would make 20 copies and sell them for 35 cents. How did you sell those copies? Who were the first readers to buy King-Cat?

I’d keep one, give one to my dad. I had six or seven friends I’d give copies to, and I’d mail a copy to Factsheet Five, drop off a handful at the local punk rock record shop. A few people would order through Factsheet Five — send me 35 cents and a stamp in the mail — or maybe they’d send their zine in trade. Some of those people from the early years are still my friends today.

You say that you never had any agenda with the way your comics have evolved over the past 30 years — that your only “agenda was not to get in the way of [your] comics.” How do you stay out of your own way?

By the time I started King-Cat I had a pretty clear idea of the way I wanted to approach things. Coming from punk rock, I was interested in paring things down, leaving them unpolished, looking for the essence of things, instead of getting bogged down in the superficial. So I wanted my comics to reflect that. They were very spontaneous. It was interesting to me to throw ink down on paper and see what came out. Even the vagaries of using cheap photocopiers, the kind of distortion and unpredictability of it — it was all thrilling to me! Putting a page of comics on the glass and seeing what came out of the machine.

In the early days I didn’t edit things or worry about them or plan them too much. I’d make a comic and print it and then wonder why sometimes I was able to achieve what I’d set out to do and why sometimes I’d failed. But I wasn’t interested in making “perfect” comics. I figured there would always be a next one, and hopefully that next one would work a little better than the last.

Mostly, I just “see” the comics in my head, and I try to put that down on paper as accurately as I can. Gradually, the way I saw them in my head evolved, and the drawings would reflect that. They started getting sparser, more simply drawn, I started focusing on the writing the way a poet works on a poem… breaking things down into syllables, meter… finding the rhythm of each comic and striving to capture that. But always I just let the comics change as I myself changed.

Your comics highlight the difficulties of living — of finding health, home, and happiness — but they just as readily offer lovely moments and beautiful experiences. How do you pursue a balance between melancholy and joy in your work?

I just try to follow my own life — there’s plenty of melancholy and joy to go around. If I’m happy, I make happy comics, if I’m sad I make sad ones. I’ve always felt a certain mysterious energy running through life. It’s there all the time, in the moments of joy and the moments of despair, and in the moments where you’re just tying your shoes for the billionth time. That feeling is what I’m after, that energy. When you become aware of it, it’s like always being home. No matter what happens it’s all right.

Many of your comics find calm in the profundity of nature. What is it about being out in nature that gives you some degree of solace?

I think nature showed me something much larger than myself that I nevertheless belonged to intimately. It’s a cocoon, it’s constantly adapting and changing, but it’s also wherever you go. Nature is perfect reality. It’s never wrong.

You once named Charles Schulz as the comic artist you would be most flattered to be compared to. What do you admire about his work?

He took a very simple premise and worked through all the nuances of it, finding emotional depth within simplicity. He created a self-limiting world that nonetheless allowed for the exploration of all of our humanity. And he worked hard right up until the end. He found something unique to offer and respected that.

You’re soon to be on tour for From Lone Mountain, and many of your comics feature time on the road. Do you write and draw when you’re traveling?

Well, I write in my head all the time. I’m constantly jotting down ideas and turns of phrase on the backs of receipts, recording stuff into my phone. I mostly only draw when I have to. I’m not one of those cartoonists that’s doodling on napkins during dinner. But I will be writing down notes during dinner.