Kate Zambreno’s first book, O Fallen Angel, was released in 2009 by Chiasmus Press as the winner of its aptly titled “Undoing the Novel” contest. This was also the year I moved to Chicago, the city where Kate then lived. There, O Fallen Angel was insinuatingly suggested to me by a bookseller at Quimby’s, offered as a kind of (anti)social talisman: “Have you heard of Kate Zambreno?”

I bought the book, went home, and filled a bath. I read from the opening — “There is a corpse…” — to the end — “…it was nobody’s fault.” I paused for a moment of breathless unsureness and horror. I drained the bath, refilled it, and reread.

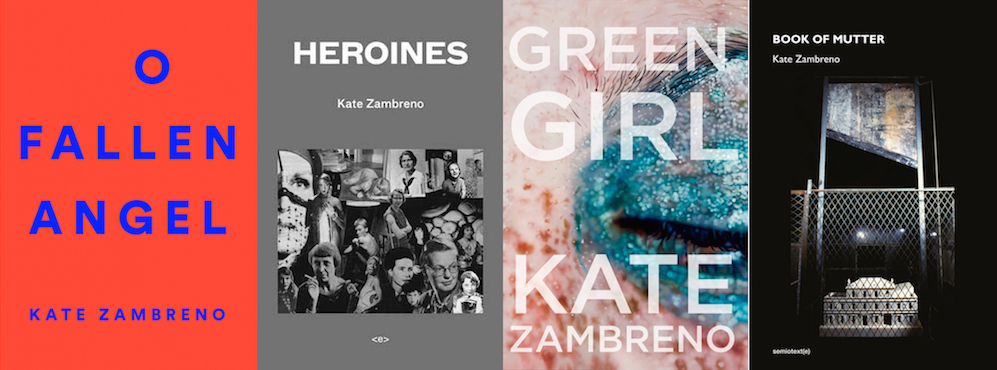

Since then, Kate has published Green Girl (2010), the existential novel of a young, American flâneuse in London; Heroines (2012), a book-length essay on the subjugation and subversive friendships of female writers; and most recently, Book of Mutter (2017), a hybrid meditation on mothers, motherhood, creative birth, and loss. It feels fitting that the Harper Perennial re-release of O Fallen Angel coincides with Book of Mutter, a full-circle synthesis of beginnings, endings, and re-beginnings.

MEGHAN LAMB: Feeling my way through the many conversational layers of your texts — layers of Sarah Kane, Marguerite Duras, Violette Leduc, and Anna Kavan; layers of Louise Bourgeois, Roland Barthes, and Henry Darger; layers of distinctly Midwestern landscape — I realize there are so many places I could begin from. I am reminded of Nathalie Léger, who was assigned to write a brief article on Barbara Loden’s film Wanda and ultimately wrote an entire book, Suite for Barbara Loden. Léger writes: “I felt like I was managing a huge building site, from which I was going to excavate a miniature model of modernity, reduced to its simplest, most complex form: a woman telling her own story through that of another woman.”

This idea — one woman telling her story through another — feels like something that has always been at the heart of your work, from the familial polyvocality of O Fallen Angel to the archival, preservational impulse behind Book of Mutter. What is your experience of speaking through other women’s voices, and how has that experience changed over the course of your writing career?

KATE ZAMBRENO: When I began writing, not intimately knowing other living writers, I thought of my work as a form of séance with mostly dead writers, some sort of ghostly visitation — with the writers that you mention, others, and then myths or figures who were failed writers, or erased somehow. That is some of the impulse behind Heroines. To write as if I was already dead, to paraphrase a line from Marguerite Duras. Actually…I’m not sure Duras actually wrote that, or that the line hasn’t been altered in my remembering it. But I do think that’s still the major drive or nervous energy behind why I write — that desire to commune. Perhaps that’s loneliness ; I don’t know.

Lately though, in this new series of small prose texts that I’ve been working on, I’m more interested in exactly what you expressed — the uncanny correspondence between living writers, the writers we share, the obsession with certain tragic figures, or hermits, or suicides of a sort, those chimings. I’ve published little in the years since Heroines, and have done a worse job turning anything in, but I’ve continued these often passionate and engaged correspondences with other writers. And then there are also the correspondences I feel reading their work, and the writers and artists we share.

I’ve been thinking of these texts, of which my in-progress Drifts is kind of the first one, under the genre of “friendship,” like Bernhard’s Wittgenstein’s Nephew. Drifts deals a lot with friendships I have with other women writers, and about our conversations, like the writer Sofia Samatar and I speaking of Kafka and Rilke, wanting to be Kafka and Rilke. A community in the Blanchot sense.

And bringing in the Léger — I’ve been obsessed with Barbara Loden and her film Wanda for a decade; she’s in Book of Mutter. When I read Léger’s text, at first I felt like Salvador Dali, upon viewing Joseph Cornell’s collage-film Rose Hobart (Cornell the obsessive, the archivist, the collector), knocking down the projector in a fit, claiming that Cornell stole his idea for a film, he stole it from his dreams. But really I celebrate this ghostliness, this porousness, that the writers I read are reading the same texts, obsessed with the same figures. With Robert Walser and Ingeborg Bachmann and Jane Bowles and Marguerite Duras and W. G. Sebald and Ludwig Wittgenstein. My friend Suzanne Scanlon, speaking of the uncanny intimacy reading Shulamith Firestone’s Airless Spaces after writing Promising Young Women, calls it “anticipatory plagiarism.” In new work I’m quite interested in the copy, in art, as a form of theft. It doesn’t surprise me, then, to read a notebook piece of the writer and photographer Moyra Davey, whose work I’ve become obsessed with, and realize she was thinking about the biography of Jane Bowles years before I did in Heroines, or that she is writing about Chantal Akerman, like I’m trying to write about Chantal Akerman, or that in Burn the Diaries she performs a reading of Herve Guibert’s To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life, a text I’ve been thinking of constantly the past few years. Or the sharing of epigraphs, this twinning — oh, you’re using that Foucault or Cioran quote, or that Lispector or Barthes or Rilke quote, the sharing of quotes back and forth. Or even reading Joseph Cornell’s journals, and realizing he writes down the same quote from a Rilke biography in his journal that I wrote in mine the previous day…that porousness, those connections.

When I first read O Fallen Angel in 2008, I was struck by its stylistic resonances with one of my aforementioned creative heroines, the late playwright Sarah Kane. Between its atmosphere of apocalyptic — yet deeply personal — dread, its mixture of caustic lines, and associative language spirals, O Fallen Angel echoed with notes of Cleansed, Crave, and 4:48 Psychosis. When you were writing O Fallen Angel, how did Kane’s voice come into conversation with your own? Were there any moments in her plays you found yourself returning to?

I felt that, too, when I read one of your texts around the same time — a piece called “Girl.” The claustrophobic atmosphere, the intensity and excess of language, that is in conversation with the plays of Sarah Kane. I do think the political dread you speak of — the writing towards an apocalyptic feeling that undergirds the plays, and how the oppressive horrors of governments and institutions and patriarchy wreak havoc on people’s ability to love and be loved, and be human — is absolutely inspired by Sarah Kane’s work. O Fallen Angel was heavily enthralled to The Oresteia, to the Greeks, to Lavinia with her tongue cut out in Titus Andronicus; but it was always the Greeks or Titus through Kane.

But there’s a purity to her work, even amidst all the violence and excess, that comes out of a burning sense of empathy and hypersensitivity to the vulnerable, to the dehumanizing torture of love and war. She expresses an almost hypnotic pain at the suffering of not only the self, but also others. There is such a tenderness even amidst such abject cruelty in Sarah Kane’s work, an empathy and humanity amidst prisoners of war. The Mommy figure in O Fallen Angel is an oppressor — a friend of mine wrote to me when it came out: Mommy is the Bush administration! And I think that’s true — there’s not much tenderness in my grotesque of her, although I do think I attempt to render her isolation, her sadness. I do think there’s an extreme sadness to the daughter figure, to Maggie, to her tragedy and pain — even though she is also a cliché. Kane’s characters always touch each other, although in often violent ways; the figures in O Fallen Angel are more static — they don’t touch each other.

Especially with this grim landscape now, this almost inarticulate and unraveling dystopia — god, Sarah Kane is more urgent and relevant than ever right now — I think so often of that impossible stage direction in Cleansed: that a sunflower is supposed to push up through the floorboards and grow up through the actors’ heads, at the most grotesque moment, when Carl is completely dismembered, when the rats are supposed to carry his feet away.

For me, some of the most captivating aspects of Kane’s work are these very un-performable directives, moments like the sunflower pushing through the floor, the rats carrying away Carl’s feet, the sunlight that shines so brightly it becomes blinding, the rat squeak that grows so loud it becomes deafening. These directives were not only left open for interpretation by the reader; in a way, they were only made possible within the reader’s imagination, thus imbuing them with a tremendous responsibility for the play’s outcome.

The harrowing opening lines of O Fallen Angel invoke a similar kind of interpretive openness and responsibility:

There is a corpse in the center of this story

There is a corpse and it is ignored

No one looks at the corpse

Everyone not-looks at the corpse

This beginning is compelling because it functions not only as a call-out — planting the horrifying knowledge that for the entire book, we’ll look on as its subjects mill around, not-looking at the corpse — but as a profound negation, the outlining of an absence. How did your sense of the un-performable absence — the unspeakable, the inarticulable — play into the development of O Fallen Angel? In light of its re-release, and of recent events, do you feel our responsibility for the corpse has changed?

I think of those two sections flanking the book as, in a way, mocking Greek choruses making these blanket societal statements. I think it’s less of a directive to a reader, although that’s really interesting, and more of a commentary on what is not said and what is erased within a dumb and oppressive familial structure. And then, the larger society that represents it, an American society in wartime, and the desire of oppressors to ignore victims and casualties, to not see them as human. I don’t think I’m saying the reader ignores the corpse — but I like thinking about that — but that people within this Midwestern and Catholic landscape are ignoring or demonizing the figure of Malachi, self-immolating in protest against the war, and ignoring or gaslighting the psychotic depression of Maggie. So I was writing towards a specific normalizing and silencing environment, that wants to vilify or silence or dismiss protest, in these two different forms.

If I were to try to characterize this period of work, or find some link between O Fallen Angel and Book of Mutter — two very different texts, in a way — it is this interest in what you characterize as an “unperformable absence,” the repeating image of the open gaping mouth of Francis Bacon, the silent scream of Helene Weigel in Brecht’s Mother Courage. I think in both texts I am attempting to give language to an unanswerable grief, or to what cannot be articulated or spoken. I think in O Fallen Angel this is why I make the consciousnesses of Maggie and Mommy so clichéd and inarticulate, but then underneath, there is this rage and grief and deep sorrow that they are expected to put away.

O Fallen Angel and Book of Mutter both revolve around the shape — or absence — of a mother, albeit in very different ways. I can’t help but think of Anna Kavan, who reimagined, retold, and revised the story of her shadowy, distant mother, over and over again. How has the shape of mother — of mommy — shifted through repetition, through redoing (undoing,) and retelling?

I love thinking of the project of literature as one that’s ongoing — that doesn’t end with the completion or publication of a book. In some ways we are writing the same texts over and over again, attempting something and failing; or at least I am. I was a little nervous to have the reissue of O Fallen Angel and then Book of Mutter, this text I worked on over a decade, come out at the same time, because for both there’s this huge and overwhelming figure of the mother, this monster, and yet they could not be two more different mothers. One I imbue with something closer to hate and the other with love and ambivalence; one is overwritten and the other an absence. Although the idea of the mommy, in both, suggests something about conformity, and normalizing, doesn’t it? This oppressive force.

But what is that then — my obsession with the mother? I am collecting these closed and mysterious women, in Heroines, even in Book of Mutter. Or these memoiristic texts I write to in Mutter that circle around the lost mother — Duras’s The Lover, Peter Handke’s book on his mother, Nathalie Sarraute’s Childhood, Violette Leduc’s memoir. Having lost my mother, I guess part of the reason I started writing — and this is something I circle around and question within Book of Mutter — is to somehow point to this loss. And so there is something of the repetition compulsion, of circling around trauma, in these texts.

Even in Green Girl, Ruth is orphaned — I think, like Kavan, my earlier novels are interested in the fairytale and its poisons, and that is why Ruth must be orphaned. What I have always found striking about Kavan’s work is that quality of rewriting. In the later, more fragmentary texts, she is not only circling around the mother — this cold figure that keeps on repeating in the novels — but also how after her breakdown her texts began to break down, to repeat, become extraordinary. The feverish intensity of Who Are You? becomes darker, more dystopic, and stylistically a much more naked version of an earlier, more conventional novel written under another name.

In Book of Mutter I circle around Barthes revisiting the photograph of his mother in Camera Lucida and writing about her in the days after her death in Mourning Diary. In the book I also think to the art of Louise Bourgeois and Henry Darger. Both are artists that made these monuments out of a desire to somehow exorcise the trauma and mythologies of childhood, still stuck somehow within the Oedipal family structure, within childhood, that sense of art as necessary to survival for both of them. I think the artists and writers that I’m most drawn to are fixated, obsessed, and their work is imbued with that compulsive and ritualistic energy.

Book of Mutter reads as a beautiful archive of your mother: the haunting phrases, artifacts, and fragments of memory that fill her outlined shape. From my naive perspective as a reader, this book feels so whole, so complete in its construction, that it’s difficult to imagine it could’ve been written any other way. I know, however, that over 13 years of researching, reflecting, and molding the shape of this book, there must have been numerous potential strains that haunted your writing, but never reached the final text. Could you share some of those strains?

I like the idea of haunting — these ghosts of other texts that could have existed — and I think Book of Mutter, in this final incarnation, contains these shadows and echoes. One of the ways I can answer this is something akin to describing process: usually, for years, I work on several books at the same time, usually in some crisis, feeling I’m failing at all of them. It’s like this big block of ice that I keep on shaving away at, and not knowing whether the book is the block of ice, or whether the books are the shavings that are coming from the block of ice, this frozenness. A lot of the energy — my madness, my obsession — is trying to figure out whether I’m writing one book, or two, or three. Or what is this book, what is that book, how do they all bleed into each other?

It sounds quite defeating, but that’s how I work. I try to find the boundaries and borders of a larger project — of ideas, figures, obsessions — that often feels borderless, and make constant notes about it, and then realize the notes are the writing, and so on. I guess that all the texts that have been published as of now, including Mutter, were composed in the same period, although I held onto Mutter for much longer, continuing to rework and revise it. And there have been so many dead ends — but somehow the failures of other texts still haunt the texts that do exist, the ones that managed to somehow be finished. I failed at Book of Mutter for so long that it’s contained so many different incarnations. There’s a list at the back of the book of everything the text once contained, all the furious energies of research within it.

For a long time, since I was writing about suffering, and the body in pain, these private archives of grief, I became obsessed with atrocity, with iconic photographs of pain and suffering. I was obsessed with photographs of concentration camp victims, records kept at Auschwitz, the Torture Archives, the Tipton Three, the photographs from Abu Ghraib, the photograph of the Chinese victim of lingchi, or death by a thousand cuts, that Bataille was so obsessed and repulsed by. And then Sontag, reading Bataille, reading the photograph.

And there were all these threads about Duras’s screenplay for Hiroshima mon Amour: Duras basing her screenplay for Hiroshima mon Amour on the phenomenon of white Western women with broken hearts flocking to the Hiroshima museum a decade later. In a way that was totally absurd and appropriative, and yet I understood it. Like what Sylvia Plath performs with history in “Lady Lazarus.” In previous versions of my manuscript, I was repeating the image of Emmanuelle Riva going mad in the cellar, her head shaved, which mirrored Renee Falconetti as Joan of Arc in the Dreyer film — imagery that’s still in the text. I think one of the things I wanted to answer in Mutter, with these threads, was what image, what book, what event from history, can we grasp at, in an attempt to access our personal trauma? This fixation is still in the book, but much much less so.

Also, Book of Mutter was, for a while, so much about the lies and records of American history: this vast amnesia dealing with torture and interrogation, Alberto Gonzalez repeating “I don’t recall” ad infinitum, more stuff about Lincoln and Mary Todd Lincoln and her insanity trial…I don’t know. There was a lot. Stuff about FBI files and surveillance of Marilyn Monroe. Some of that stuff is still there, I think the book is still about history, and the present, and America, but it’s more about a private archive. This final version is much more pared down, I cut and cut and cut away…

But I think there were infinite possible variations of this text. Thomas Bernhard said something like, you have to publish so that you can finish the text. So in this way, the book is finished, in its final form; but also, I’ll probably always be writing to it, to what catalyzed the project. I tell myself I’m done writing the mother, but then in new work I’m newly obsessed with Chantal Akerman’s films, that are so much about the mother, I’m still obsessed with Barbara Loden and her absent mother in Wanda, my obsession with Joseph Cornell, with Rilke, with Barthes, is still somehow about the mother.