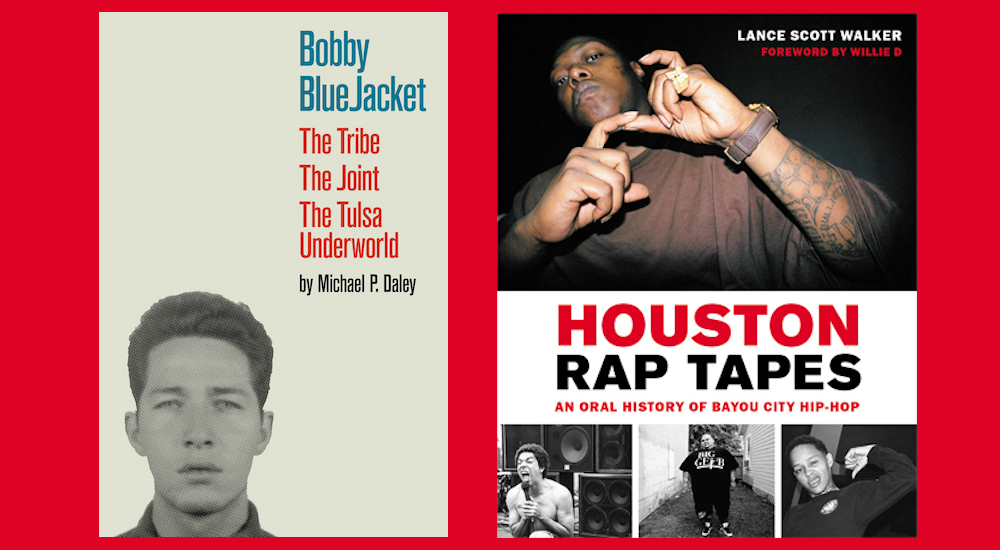

Michael P. Daley, author of Bobby BlueJacket: The Tribe, The Joint, The Tulsa Underworld from First to Knock, and Lance Scott Walker, author of the forthcoming Houston Rap Tapes: An Oral History of Bayou City Hip-Hop from University of Texas Press, have both written about people who have done less than legal things in their lifetimes. Below they talk about the delicate balance of telling another person’s life story.

¤

LANCE SCOTT WALKER: I think we should start with Larry Clark, because that was your entry point. I transcribed some tapes for him years ago, and I believe that those tapes were where you discovered Bobby BlueJacket.

MICHAEL P. DALEY: Your transcription is how I heard of BlueJacket for the first time.

I mean I know what’s on those tapes — hustlers, junkies, bullshitting, fixing. There’s Billy Mann, who would later end up dead, tangential to BlueJacket. Larry Clark himself is on those tapes. So of all the people, all the crazy characters that Larry recorded back in Tulsa in those room recordings, what stood out about Bobby BlueJacket?

I was working with Larry on doing an annotated history of his photography book, Tulsa. I would highlight all the names on this transcription, and then interview them or chase down old newspapers, microfiches, things like that to try and provide some context. One of the names was BlueJacket. And the context of this mention was Billy Mann and two other guys complaining about how one of them couldn’t bond out of jail over some thing or another, and the one guy says, “Oh, man, you better talk to BlueJacket,” as if BlueJacket could fix the problem for him. Immediately the name was so visceral and unique. Then I asked Larry about it a week later, and he was like, “Oh yeah, BlueJacket — he was an outlaw legend that gunned down this other kid in like a teen rumble in the late ‘40s.” It was a feud that happened at a hamburger stand in 1948 between all these teenagers, so it stood out to me as this American juvenile delinquent trope, years before it was actually a trope. That set me down this path, but I didn’t come across much about BlueJacket working on that project for another few months at least. Ron Padgett, who’s a famous New York poet, but he’s from Tulsa, had written a memoir about his father, who was a legendary bootlegger in Tulsa back in the day. And BlueJacket was actually a subject, or a source, for Padgett’s book. So, still thinking I was working on a Larry Clark project, I contacted Padgett, who then put me in touch with BlueJacket, and I called him.

Once you started talking to him you were like, “Oh, I gotta write about this guy! I gotta go deeper with this guy.”

Yeah, because first off, his voice is really musical, and the way he talks it’s like there’s zero emotional restraints. He was really in touch with himself and yet also was an extremely hard, tough dude. Career burglar. Did multiple stints in some serious prisons, but still again was this kind of heartfelt guy, so that tension attracted me. And then after the interview I did with him, I started just asking him about his own life, and he started telling me the tale of how he had grown up in the alleys of Tulsa, hustlin’ newspapers, hangin’ out with older, junkie safe burglars.

So we have a guy who’s in and out of prison, but in that experience of being in prison, finds a whole other side of himself, without having a world in which to thieve. Incarcerated, he starts to write and finds a whole new way to express himself that keeps him out of trouble.

BlueJacket has told me about it, that his entire youth up until he was 18 — which was when the killing occurred and he went to prison — he never gave himself the opportunity to look inwards. He grew up on Eastern Shawnee land in northeastern Oklahoma. He was born in 1930, and a few weeks after, due to a tumultuous home life up there, his mother took him to Tulsa. He was then taken to the Seneca Indian School, which was an Indian boarding school. It was part of this larger campaign in the United States to try to make Native Americans white, essentially to destroy all their Native culture, religion, language…

Cut their hair, change their names. Like the residential schools in Canada.

Right, so that off the bat I think put him in a very negative point of view as far as appreciating yourself. And then his youth after that was basically spent largely going in and out of juvenile reformatories. When he wasn’t in reformatories, he was hanging out in pool halls, in alleys, runnin’ around goin’ on burgle trips regionally — the way he says it, if he hadn’t been incarcerated when he was 18, he would’ve probably ended up dead by the time he was 22. When he hit the penitentiary, he arrived at a time when this kind of draconian, dungeon-like atmosphere was turned into a pilot for rehabilitation programs. Things had gotten so bad by the late ‘40s that the state government and the Charities and Corrections — which was an early version of the Department of Corrections — commissioner appointed a new warden named Joe Harp. And this Joe Harp guy basically took the rotting state reformatory where BlueJacket was at the time and created a prison newspaper, prison grade school, and high school that became the first accredited one behind bars. And sports teams and other programs encouraged the human being and the cultivation of a sense of identity and self that did not exist before. And BlueJacket happened to be one of the key poster boys for these programs. He became the editor of the newspaper, he was in a variety of positions on the baseball team, would be hotdoggin’ his way across the diamond.

Transferred to another prison just to be on their baseball team.

That would be Oklahoma State Penitentiary, which is the big one in McAlester, and his baseball career was advancing enough that he wanted to get back to McAlester where more baseball scouts were. Around 1953 he was trying to get noticed so he could get pulled out of prison and join the big leagues. As crazy as that sounds, it did occur occasionally at the time.

Then he gets out. He goes straight for a while.

He got out in ‘57, which his original sentence was 99 years, so it was a few different stars aligning, but he was able to get out, he got straight, and got into the used tire business, which involves basically driving out, looking for tire farms, which are dumps of used tires, junkyards. That took him all over the country, brought him up to Minnesota, where he was livin’ big for a while, and then he unfortunately got caught up in some stealing again. He did vacillate between straight life and thief life, but I think that’s more interesting and more true to life. Often your generic prison story is someone who goes to prison, is miraculously saved, and then their life is completely normal afterwards. And I think for BlueJacket, the way he’s told it to me, his was a lifetime of finding himself and getting on a path that he felt comfortable with, and that involved a lot of back and forth. A lot of good, a lot of lawbreaking. Making family, losing family members. I thought the story was interesting from that angle in the sense that it’s not some kind of Hollywood arc.

But by the time you get to him, the natural arc of his life has brought him to a point where he’s very much at peace, more deeply connected to his Shawnee culture — which he has embraced his entire life but was never as connected to as he is now and serves as a really important member of his community.

He had gone to prison again and got out in ‘93, and at that point, some friends had invited him up to the tribal grounds, which again is up in northeastern Oklahoma, nearby the town of Wyandotte. I think that he felt a kind of calling to the cultural and spiritual side of the tribe in terms of getting in touch with his ancestors, with his family, with the idea of history. Because he had lost sight of that pretty much after he’d gotten out of Indian School in 1944. He’d fully fallen in with I guess you’d say white life in Tulsa and in Oklahoma. So it was really only in the mid-‘90s that he started getting in touch with these cultural roots again. And then I think probably the biggest thing for him was that he saw a way to materially do good, in the sense that the tribe has all these programs — you know, there’s something called an Elder Crisis Committee that he works on where he’s helping repair houses for impoverished older members. He’s driving around trying to solve problems in a very pragmatic fashion. So I think that gives his life a lot of purpose as well.

And he’s writing a lot.

Oh yeah. He’s a prolific writer. In the old days, he’d write for both the prison newspapers but also your outside newspapers like Tulsa World, Tulsa Tribune. He’ll still occasionally do that today, but also writes for The Shooting Star, which is the Eastern Shawnee paper. Pow-Wow magazine. He writes a lot of speeches for political matters of the tribe, also eulogies. You know, that’s something I also enjoy about him is that his writing is very beautiful and has its own style, but it always has a purpose.

What was the research process like in determining how to tell the story of the killing? Not having a photograph or a video of what happened, or any kind of recording, based on eyewitnesses…how was that research process?

That would be part two of the book, and that is probably the part that changed the most from the beginning to the end. I guess two big influences on that section would be Errol Morris’s A Wilderness of Error, and then also Carlo Ginzburg’s The Cheese and the Worms. Both just in the sense of how to treat raw legal data, and how much to infer versus just present. And so my original idea actually was just pretty much reproduce the transcripts, and that’s it. Let people look into it and deduce anything they can. But that, upon reflection, seemed to be asking too much of the reader in a way, where it’s like over time I tried to then put some of the transcripts into prose, provide more context, and highlight what BlueJacket’s interpretation of that trial was. Clearly show where he’s pointing to where the injustices were, but also leave it open to the sense that me as an author…I wasn’t there, so all I can do is just juxtapose sources that were there, or were adjacent to it, like the newspaper articles. I don’t know — court cases even two months ago, much less 60 years ago, are always interesting because it’s like your conspiracy theory muscle of the brain wants to know why they did it, how they did it, did they do it? But I feel like the reality is, like most things in life, we can never really know.

It’s a delicate balance. It’s a delicate thing I think you struck in that retelling, because as I was going through that, enough was left open for every possibility to remain, which I think is very important in just writing history in general, but these are just the more fraught, more raw moments, and that one happening to be one that changed the whole course of his life.

I agree, and also on this riff, I have my own opinions on it. I personally feel he was wrongly convicted, definitely wrongly sentenced. But you also, when you try to, as the author or the historian, impose your own theory on something like that, you often undercut the argument that the reader can take away for themselves. Sometimes, by not presenting everything that happens, if it’s contradictory to your own personal viewpoint, you can undercut the strength of your argument. I thought it was important to show every possibility and every angle.

It certainly slowed down time enough. What took place over a period of just a couple of minutes is stretched out to a pretty intensely microscoped spot in the book.

Yeah, that was kind of a thing I was working with in terms of “time” with the book. Because the scope of his life is so long, now 88 years, I thought it was interesting in certain parts to blow up just a few moments into a hundred pages, and in other places it might be more interesting to cover years over two pages, kind of like a film moving at various speeds.

His life is so crazy. The way that his life unfolds in this book. He’s carved out of wood.

Oh yeah. I mean, he’s a tough guy. There’s even that scene really late in the book where he’s like 86 and some 30-year-old’s tryin’ to punch him and he takes him out where…I wouldn’t mess around with him to this day.

Whipped him with a tire iron, didn’t he?

A tire probe, yeah.

Gotta get that right.

Yeah well a tire iron’s more of a blunt strike whereas the probe is a precision instrument.

A story like this could only happen in Oklahoma.

In a lot of ways it’s an anomaly compared to the other states in the U.S., where it was originally Native land, which creates a really interesting cultural history and social fabric there. It was also, because of the Indian Territory status, early on a haven for white outlaws who were trying to escape state jurisdiction and would go hide in the various cave systems of Indian Territory. Because it was a territory, it only had U.S. Marshals as enforcement. So that meant theoretically it would be easier to hide. And so various famous outlaws like Alvin Karpis and people like that always talk about the genealogy of the Oklahoma outlaw being rooted in its very, very early days, and how that kind of leads up to BlueJacket’s time. And Oklahoma also didn’t become a state until 1907, so it was playing catch-up in a lot of ways. The Flatiron building had been built in New York and you have a bustling metropolis and then much of Tulsa didn’t have paved streets. The oil boom, which completely overhauled Oklahoma and Tulsa, didn’t really start swinging ‘til the 1900s, 1910. They also didn’t repeal Prohibition — state prohibition — until 1959. So after the Volstead Act was repealed, you still had bootleggers hanging around in ‘40s Tulsa. So there’s just this really unique society, and that fabric I think also created a perfect backdrop to BlueJacket’s life in a way that BlueJacket’s life couldn’t have happened probably anywhere else in the U.S.

I was thinking that, and not even because of his heritage but because of the frenetic paths that his life took. Oklahoma is at the center of so many things. Proximity to Minnesota takes him there and then just all over these backroads.

That regional access is interesting too in that a lot of the training BlueJacket got as a burglar in the ‘40s was due to what I referred to as an underworld triangle between Omaha, Chicago, and Tulsa, and it was basically like the thieves in each city would kinda drive in this triangular fashion trading tips and tools and joining up on various scores and things like that. And so it created this kind of… in a Midwestern way, a cosmopolitan sense about the town and the region.

They probably each had a fence in each other’s city.

Fences, tipsters, exactly. It’s a whole ecosystem, and one that’s both separate from the mainstream but also…

Feeding off of it.

Feeding off of it and living within it. That’s another thing that really attracted me to doing the book is that I feel like crime, the way it’s written about sometimes, it’s presented as being countercultural, or a “fuck the system” type-thing. But for BlueJacket’s case — and I think for a lot of the guys coming up from the Depression, serving in World War II — you know, they were outsiders in the way that they were definitely burglars, thieves. But the point of their stealing, in the way BlueJacket tells it to me, was actually to one day become a part of that norm, suburban society in a nice house and not have to steal anymore.