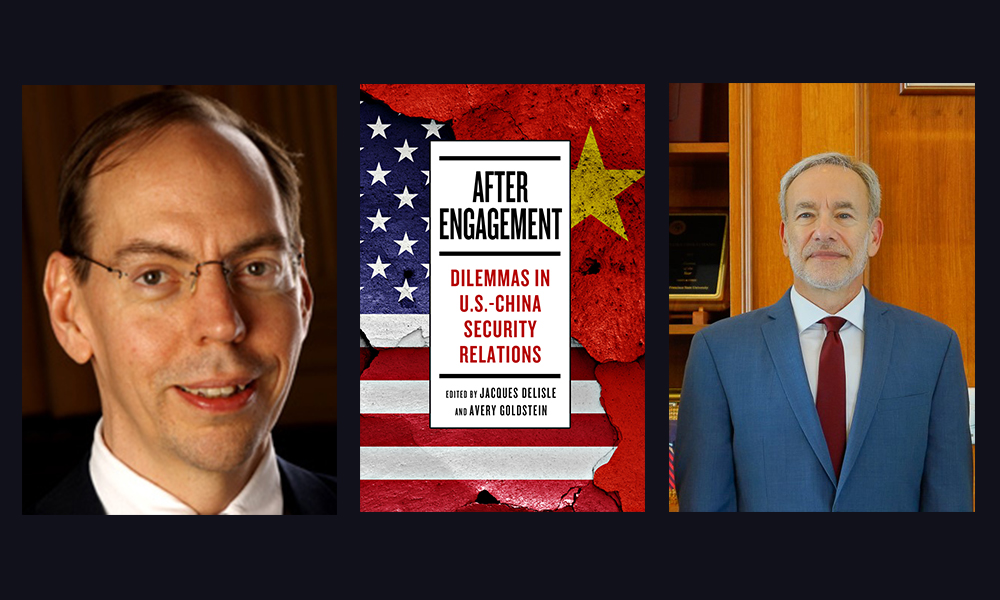

On which economic, diplomatic, and security concerns might both the US and China see “the other’s behavior as seriously threatening, and its own as merely defensive or benign”? On which such topics might US perspectives also differ from those of its Asian and European allies and partners? When I want to ask such questions, I pose them to Jacques deLisle and Avery Goldstein. This present conversation focuses on their book After Engagement: Dilemmas in U.S.-China Security Relations. Jacques deLisle is the Stephen A. Cozen Professor of Law, professor of political science, and director of the Center for the Study of Contemporary China at the University of Pennsylvania — as well as director of the Asia Program at the Foreign Policy Research Institute, Philadelphia. Avery Goldstein is the David M. Knott Professor of Global Politics and International Relations, inaugural director of the Center for the Study of Contemporary China, and associate director of the Christopher H. Browne Center for International Politics at the University of Pennsylvania.

¤

ANDY FITCH: First, with Donald Trump-style trade-war rhetoric hopefully now dissipating, but still with a broader bipartisan shift towards increased confrontation in US commercial relations with China, which early-21st-century concerns (regarding, say, China’s constraints on market access, its weak IP protections, its forced technology transfers, its export-promoting subsidies and support of SOEs) should the Biden administration consider most pressing?

JACQUES DELISLE: In terms of long-running issues that any new administration would have to grapple with, market access stands out (especially for services), as do IP rights, coerced or pressured technology transfers, and state support for Chinese firms in hi-tech sectors. Other concerns, such as currency manipulation, have faded. Emphasis on the bilateral trade deficit, a fixation of Donald Trump’s, will likely fade as well (it never really had much economic or strategic significance). But while it does seem that the trade-war rhetoric has faded, the tariffs themselves haven’t come down immediately under Biden.

I’d expect the Biden administration to focus on tech concerns: specifically coerced transfers, industrial espionage, and national-security risks from Chinese tech products. China’s industrial policy has also sped up development of capacity in some cutting-edge industries. Both sides tend to see technological competition not just in economic terms, but in security-plus-economic terms. And when nations (whether the US or China) see their national security at stake through competition in technology sectors, those concerns tend to dwarf economic objectives, and to push in the direction of less cooperation and greater conflict.

We don’t have very good tools in the international legal system or in diplomacy to handle these sorts of frictions. The WTO, for instance, was established to address a bunch of 20th-century trade problems. It doesn’t deal particularly well with state-owned enterprises, industrial policy, or technological restrictions of various sorts. We don’t have clear legal rules by which to hold each other to account in these areas. And the issues are not easily amenable to negotiated solutions, because each side sees the other’s behavior as seriously threatening, and its own as merely defensive or benign.

AVERY GOLDSTEIN: I would probably flag IP concerns as another area that may fade as a point of significant friction, for the same reason currency faded as a big concern. China gradually began to recognize its own self-interest shifting towards making the currency less fixed and undervalued. Similarly, I’d say a realization has begun taking hold (and Jacques, correct me if you disagree) that protecting IP in China also benefits Chinese entrepreneurs, both at home and abroad. Again, this change hasn’t necessarily come about due to external pressure, but it benefits foreigners as well.

I’d also follow up on Jacques’s suggestion that the new Biden administration has clarified that it shares a lot of the concerns that surfaced during Trump’s time in office, but also wants to make certain changes. Most significantly, Biden’s team wants to try for better coordination with allies, particularly with the EU and Britain. In negotiations on allied cooperation, the devil will be in the details. The Europeans may not share US views on every single economic dispute or concern with China. America’s allies and partners in Asia seem even less likely to share our perspective on every matter, especially when it comes to state-owned enterprises and subsidized industries. So cobbling together these details for a coordinated strategy to deal with China won’t just happen inevitably if the US calls for it. The US will need to listen carefully to Asian and European partners about their own distinct concerns, and figure out where their interests overlap most significantly with ours.

JL: Right, to take this back to the topic of mixing economic and security concerns, the Trump administration, and certainly its China hardliners, also pushed for an agenda of decoupling. China has mirrored that a bit in its most recent five-year plan. We face the risk of going down that path, of each side trying to hedge against dependence on the other party, trying to become more self-sufficient at least within its own bloc of close economic partners and like-minded states. Fears of significant decoupling certainly can be exaggerated. But for policymakers in either country’s capital, the possibility of a world more sharply divided into economic camps looks much more realistic today than it did five or 10 years ago.

AG: In tech sectors, at least, the Biden administration has started to articulate a more selective notion of decoupling. In terms of restrictions the US ought to impose on Chinese technology, Biden’s team seems to have adopted less of a sledgehammer approach, and more of a “small yard, high fences” approach (associated with Samm Sacks, though Robert Gates came up with that phrase), figuring out with more technical precision what we need to protect — instead of simply declaring every new TikTok the next Huawei.

Still sticking with economic concerns, could you further flesh out, but now from a post-Great Recession Chinese perspective, the precarious dependence felt by a domestic manufacturing sector so reliant on developed economies for its higher-value tech suppliers? Or with, say, the Obama administration declaring its pivot to Asia, and undertaking ambitious TPP negotiations, why again might China have seen institutional initiatives such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank not as part of some nefarious scheme to undermine the international order — so much as natural extensions of its revitalized capacities, and necessary steps to avoid being boxed in?

In key strategic industries, China feels significant concern about the leverage that its dependence provides to foreign trade partners, especially the US. In the chip sector, China has announced quite clearly its determination to become more self-reliant. They now face the reality, however, that you can’t solve this problem by just throwing money at it. You need the human infrastructure, as well as the physical infrastructure and financial investment. Most people analyzing these sectors consider China a minimum of four to six years from starting to catch up to semiconductor production in South Korea and Taiwan. That definitely concerns China. They feel the need to somehow finesse their position in trade and technology, in order to maintain access (if not directly from the US, then through third parties) to certain advanced tech-sector components they still can’t produce themselves.

I don’t see institutions like the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank as attempts to undermine, say, the Asian Development Bank, or the World Trade Organization, or the IMF. I don’t see China having a fundamental problem with those more established institutions — in part because, as Jacques pointed out, those institutions don’t feel terribly relevant to some of the biggest issues on the table today.

JL: I’d agree with all of that. When we discuss China seeking to become a major player in key emerging tech sectors, I consider that more of an offense strategy on China’s part. But China also has developed a defense strategy, to address perceived vulnerabilities, most notably in the chip sector. As we all recall from the Trump administration, threats to cut off Huawei’s and ZTE’s access to key computer chips had a real impact on Chinese perceptions of the risks of dependence on the US. And the resulting tensions have consequences for third parties. For example, Taiwan’s leading chip maker sells heavily to Huawei, but also has strong ties to cutting-edge US tech companies.

On the institutional side, I agree that Chinese initiatives are not (or at least not yet) attempts to undermine the existing order. China does have some complaints about the status quo, but not so much that it profoundly opposes the World Bank or the IMF. It engages with them extensively. You do see some concern that these status-quo institutions haven’t fully accommodated China’s increased stature. That type of perspective sharpened with the global financial crisis more than a decade ago — with China, as one of the G20, both wanting and deserving a more prominent place at the table. The AIIB, still a relatively small operation, has pledged to follow international best practices. So far, we don’t see major deviations from that promise.

Of course, from a skeptical or alarmist perspective, one could stress that China exercises much more influence in the AIIB and other regional institutions than it does in the global institutions. With that influence, China could steer newer institutions to develop rules not entirely to US liking, or could provide alternative sources of funding to countries the US and others refuse to engage.

In terms then of increasingly “securitized” policy concerns, Elsa Kania and Adam Segal sketch a likely scenario of concurrent competition and cooperation in the technology sphere, with escalating political rhetoric alongside ongoing (if diminished) collaboration in research, supply-chain, and commercial contexts. What might such a complex innovation vector look like in a couple of key tech buildouts? And over the medium-term, what would be some clear indications of a mounting “techno-security dilemma”?

AG: On the US side, much of this will get shaped by how the Biden administration handles visas for researchers (graduate students often, but also researchers more generally). Most scientific collaboration still gets organized through university-affiliated research labs. We’ve already seen some tension between academic institutions and the US government’s so-called China Initiative (mostly run by the FBI, but I’d assume with Treasury involved as well). American universities now have questions about how to ensure they’re in compliance. Chinese researchers and students worry about what risks they might run while in the US. And Americans partnering with Chinese research teams face new doubts about moving forward with these pretty deep-rooted relationships. Depending on exactly how the US presses ahead pursuing its related concerns about espionage, that could really exacerbate the anxiety currently felt by all parties.

JL: Cooperation used to happen pretty easily. The US-China relationship didn’t seem as prone to competitive or adversarial dynamics. Everybody recognized China had a long, long way to go to catch up in tech sectors. But as China has grown more powerful and the tech gap has begun to close, cooperation no longer feels cost-free to the US. Maybe we can still recognize that a modest competitive dimension might be positive for all sides. But as Avery noted, the growing sense that national-security issues are directly in play has started to make cooperation more difficult on a wide range of topics.

If you want to gauge how serious the negative trajectory might be, I’d look to how the Biden administration frames some of its main tech concerns. If issues that we’ve long thought of as primarily economic now get reframed as tech-security issues, and if more and more technologies get put into the bucket of national-security-sensitive technology, those are signs of a bad relationship. If this happens for legitimate national-security reasons, fine. If it occurs through error, that’s not good. But if it comes about as part of a disingenuous political strategy, reflecting domestic anti-China politics (or as part of some questionable negotiating gambit), so much the worse.

We could see more questions along the lines of: “How can America have Huawei supply any equipment if it means security trapdoors?” We’ve already heard this, and more — even fears that D.C.’s Metro subway cars, if made in China, could potentially operate as listening devices. When concerns reflect an accurate assessment of the risk, obviously we need to take them seriously. But when they start to spiral, based on ill-founded exaggerations, then we have a problem crafting policies that serve real national interests.

Part of the complexity in assessing these issues comes from not knowing how dangerous, from a national-security perspective, new technologies might be, because neither side feels confident it fully grasps the other’s position on some key strategic questions. Operating in that kind of information vacuum means that security-dilemma dynamics are more likely. If someone of ill will could exploit new technology to inflict harm (even though a purely benign use of the technology also remains possible, even likely), then we do have to worry about the bad outcomes, and hedge against them, and be prepared to deal with them. Accomplishing that could involve going down the path of decoupling, or limiting which technologies we share or adopt, or finding ways to mitigate risk — which sometimes, but not always, can be taken care of by tweaking the technology, rather than adopting more disruptive or provocative measures.

AG: Right, in most of these situations without a clear and obvious security concern, we still face questions about tradeoffs between the benefits that come from sharing technologies, from foreign investment in infrastructure, and other forms of engagement — and the risks that can’t be completely eliminated. Clever lawyers can envision scenarios in which, for example, rail cars manufactured by a Chinese company in Springfield, Massachusetts look problematic if one asks: “Can you be absolutely sure that nothing sinister or compromising was introduced earlier in a supply chain that reaches back to China?” One can run such logic out to its silly conclusion, in which case there’s no way to disprove this kind of negative proposition. The more reasonable questions focus on how best to mitigate legitimate risks, rather than unrealistically expecting to fully eliminate risk before enjoying the benefits of exchanges with China.

Still in terms of security dilemmas, when reading this wide-ranging collection, questions that do stand out tend to be the biggest, most foundational interpretive questions. So could we take up, for instance, Jessica Chen Weiss’s inquiry into whether the Chinese Communist Party primarily seeks to make the world safe for itself (by eroding certain liberal norms, values, and institutional checks), or whether it seeks fundamentally to remake this international system from which it has so benefited in recent decades? Could you sketch the broader stakes of that kind of question?

AG: It depends which norms. I mean, when it comes to one of the deepest-rooted international norms, the norm of state sovereignty, China has stayed pretty rigorous about opposing regime change. They’ve meddled through propaganda outlets, and Chinese student associations. But China has not, since its Maoist days, had the kind of foreign-policy agenda that the US has pursued in promoting regime change. China has instead acted opportunistically, accepting regime change that clearly benefits China, but also accepting regime changes that you’d think they’d find ideologically unpalatable.

For example, China has been pretty flexible in its approach to Burma over the past decade, working with whatever regime is in power. In Ethiopia, same thing. China had no problem with Ethiopia’s authoritarian regime. When Abiy became premier and pursued democratic reforms, I wondered whether China would continue the close relationship with Addis Ababa — and they did. That said, I suspect they don’t much mind now watching Abiy act a bit more authoritarian himself. I see Beijing as agnostic on these governance issues outside of China. Some people might think of this as tolerating or abetting a worldwide erosion of democratic values, and a broader drift back towards authoritarianism. But I still see that as different from positively pushing a regime-change agenda.

JL: I agree that the answers depend on how one frames the question. Anyone familiar with US-Soviet Cold War competition probably would consider it a real stretch to describe China today as trying to install puppet regimes the way Moscow or, arguably, Washington did. But if you work from the perspective of tracking China’s behavior over the past generation, you might emphasize the drift towards a more authoritarian political order under Xi Jinping. You’d likely focus on a shift towards a more self-confident China starting to present its political model as having important lessons to teach others. Measured against that baseline of relatively recent history, China does look more assertive today.

But I take your question, Andy, as asking how and whether we can distinguish between China just trying to make its way in the world, and China trying to remake the world in ways that suit China. One message of Jessica Chen Weiss’s chapter is that this isn’t a black-or-white or binary question. China may have no agenda for trying to make other states’ regimes change to look more like China’s. But in its efforts to “make the world safe for autocracy,” as Weiss puts it, China also has sought to create a buffer against pressure from the US and other Western states. China has succeeded in creating some space in which it can play by its own rules, both domestically and globally (for example when it comes to human-rights concerns). Some of this is a manifestation of China’s strong support for state sovereignty. China’s agenda may not go beyond trying to ensure that autocratic or authoritarian regimes don’t face the kind of international pressure they otherwise might. That agenda does not entail China trying to export an authoritarian model, but it does corrode liberal norms and related aspects of the current international system.

AG: I’d also note, as you suggested Andy, that one theme in Weiss’s chapter (and a lot of the book’s other chapters) has to do with clarifying what we see from China right now, while also making clear that we can’t say for certain whether China might act more assertively or aggressively, or more openly advance a foreign policy promoting authoritarianism, in the future. In part this will depend on what others, including the United States, do. That does lead us towards something like the security-dilemma logic: with China perceiving a threat to its values, and responding in ways the US regards as a more assertive China promoting its threatening authoritarian vision.

With some of those strategic calculations in mind, how much do we also need to differentiate among the perspectives and interests of Xi Jinping, the CCP, the Chinese state, and “China”?

AG: Well, in its last year the Trump administration definitely displayed an overt agenda of trying to distinguish between the Chinese people and the Chinese Communist Party. That tendency has at least partially carried over to some in the Biden administration, who sense there might be differences worth trying to exploit within the Chinese leadership. But I wouldn’t draw any clear lines between the party and the state. You might see certain competing interests and differing perspectives. But I wouldn’t think of these as interest groups. I mean, the party’s clearly in charge.

I’d also consider it risky to assume that if Xi Jinping falls ill or gets replaced tomorrow, a change in the person filling the top party leadership post would fundamentally alter the types of considerations we take up in this book. A lot of what we’ve seen under Xi already had started appearing during the last few years under Hu Jintao. These developments reflect much broader changes brought about through China’s increased wealth and power — as well as an intensifying nationalist sentiment that has affected China’s foreign-policy goals, and the way it deals with the US. I’d expect a post-Xi Jinping leadership to be different for sure, but not fundamentally so.

JL: Our cowritten overview chapter argues that many problems After Engagement addresses have existed for longer than it may first seem. A variety of contingent circumstances (September 11th, for example) helped to mask long-term trends. Pressures giving rise to security dilemmas and genuine conflicts of interest have, for some time now, been structural features of this shifting distribution of international power in China’s favor — made worse by differences between the US and Chinese political systems. That’s not all inevitable. Both sides make political choices. We do have some agency when it comes to coaxing good outcomes, and avoiding bad outcomes. But a lot of the friction and the underlying tensions will persist in any case.

That said, one basic point in this book is that neither China nor the US is monolithic. Both have various political actors with their own interests and agendas. China’s engagement with the world has grown vast and complex, with many diverse participants, who have some latitude to pursue divergent goals. The same, of course, is true for the United States.

James Reilly’s “China’s Belt and Road Initiative” chapter likewise raises elemental questions regarding how the US and its allies perceive China. Where might we mistakenly project, for instance, a grand sense of purpose to BRI undertakings? Where might the BRI in fact rebrand decentralized pursuits of countless self-interested actors, rather than harnessing some world-historical geopolitical campaign? What might it look like for the US to properly recognize (but not to exaggerate) the very real stakes involved in this “core technique of China’s orchestration approach to economic statecraft”?

AG: Reilly’s chapter does a good job pointing out the Trump administration’s mistaken approach, which characterized the BRI as a geostrategic masterplan for China to expand its influence and become the dominant global power. This view makes too much of the BRI. Many investments associated with the BRI had already been underway for years.

I sense (not just in the D.C. think-tank world, but also among people in the Biden administration) a new openness to the idea of not reflexively countering the BRI, but instead trying to figure out ways to complement certain BRI goals. This could take the form of working with China in some countries with ongoing BRI projects, or tapping our comparative advantages and experience to offer the kind of expertise (including legal advice) that would enable countries to strike better deals with the Chinese. Such assistance might help recipient countries better identify problematic implications of some BRI projects for their labor markets, or for their environment.

At the same time, Reilly’s chapter usefully points out how it has harmed America’s interests to constantly harp on the idea of the BRI as a Chinese plot to manipulate or dupe nations throughout the world. That didn’t resonate well in many countries with BRI projects. It generated a response along the lines of: “So you’re telling us keep the Chinese out. But what’s our alternative? We don’t see you offering one.”

JL: What we think of as the BRI includes many different actors in China pursuing parochial interests: big companies trying to make a buck, provincial governments seeking to score political points with the national leadership and secure economic opportunities for their localities, and so on. Those factors matter much more for shaping the BRI and China’s broader international behavior than is often recognized in our discussions of Chinese foreign policy.

Pivoting then to specific potential flashpoints, Charles Glaser’s “Assessing the Dangers of Conflict” chapter suggests that US-China tensions over Taiwan epitomize certain classic security-dilemma dynamics. But Glaser also shows that we don’t simply have a textbook security dilemma here — that reassuring knowledge alone cannot resolve this conflict, in which both sides see a vital security interest at stake. What options (if any) does the US have for helping to shape an acceptable Taiwan status quo that can coincide with China’s continued international rise? And what arguments can the US offer for why China should see regional stability as still in its own economic interests?

JL: Glaser’s chapter argues that many aspects of the US-China relationship display the features of a security dilemma. Neither side is sure of the other’s agenda, and so has to hedge against the possibility that the other side’s agenda is aggressive. But Glaser also sees genuine conflicts of interest, which differ from a security dilemma. In principle at least, security dilemmas can be handled largely through sharing better information (although another chapter, by M. Taylor Fravel and Kacie Miura, makes the further point that sometimes additional information just hardens views). But better information is less helpful where the parties have, and properly perceive, incompatible interests or preferences.

How does this apply to Taiwan? In Glaser’s view, the US and China face more than a security dilemma. Glaser argues that China has a national-security interest in gaining control over an area so close to China, which it already considers part of China — while the US has a security interest in supporting friends and allies in the region, which includes checking China. Each side considers its own actions benign and status-quo preserving, while seeing the other side’s actions as aggressive and status-quo upsetting. In these specific circumstances, when the relevant parties proceed from such fundamentally different understandings of the situation, more information won’t help much.

Moreover, over the past few years, since Tsai Ing-wen became the Taiwanese president, China has pushed a narrative that she is stealthily moving Taiwan toward independence. The US doesn’t see it this way. Neither side is likely to persuade the other. Yet clarifying US policy might help. Our current policy of strategic ambiguity (leaving it a bit unclear, for example, under what circumstances the US would come to Taiwan’s defense — while simultaneously seeking to deter any Taiwanese push for formal independence) has its logic, and has been an effective policy for many years. But that ambiguity also leads to suspicion and, in turn, the risk of security dilemmas.

The alternative policy, discussed more now, of opting for strategic clarity, by signaling a stronger US commitment to Taiwan, might mitigate the security dilemma. But it also may sharpen perceptions of a genuine conflict of interests.

AG: I’ll just add one thing. In this particular situation, we don’t just have US and Chinese interests at play. We also have Taiwan’s. And of all three players, only the US seems genuinely happy to live with the status quo indefinitely. Some in the US have committed themselves to Taiwanese independence, but the main thrust of American policymakers, in both parties, has been a willingness to live with the status quo. By contrast, and despite what you hear from some of the more realistic people in Taiwan (and some of the more realistic people on the mainland), their commitment to the status quo is far from ironclad, as is clear if one asks for clarification. At a minimum, Taiwan wants to play a more substantial international role, akin to the role played by nation-states, with membership in global organizations. They want international respect, and they’re not satisfied with the status quo. The status quo doesn’t satisfy Beijing either, because it feels that Taiwan needs to accept eventually being politically integrated with the mainland. So these three different perspectives further complicate the ways that Beijing and Taipei interpret US policies and actions relevant to cross-Strait relations.

Many people in Taiwan would like a push for full-fledged formal independence, if it could be achieved without a national crisis or war. But China has made clear that it won’t tolerate a Taiwanese push for independence. So the enduring, if reluctant, acceptance of the status quo that one sees (to a large extent) in Taiwan reflects concern about how China would react to any steps towards independence. Nevertheless, some in Taiwan pressing to move further towards independence worry that Beijing will increase its pressure — and that without US help, Taiwan will gradually be overwhelmed by China. They are aware that although Xi currently tolerates the status quo, like all CCP leaders he has repeatedly stated that he expects Taiwan’s unification with China.

With all these cross-cutting interests and preferences, the Taiwan issue is destined to remain a chronic problem of varying importance in US-China relations. During the decade before 2016, the issue wasn’t seen as a likely flashpoint. And perhaps the dangers will recede again. But disagreements about Taiwan’s future status will not disappear, and can be expected to resurface.

More broadly for the region, Phillip Saunders sees the potential for a new equilibrium to take hold, with China strengthening its position on territorial disputes, but also reaching a threshold at which further gains, necessitating more overt use of force, would come at too high a cost. What role will the US play in helping to determine whether (and for how long) such an equilibrium can endure — and can benefit most parties?

AG: For a long time, the US said that American primacy needs to be “preserved,” and then more recently “restored.” But overall, I see that kind of thinking fading. I mean, even some of the more hawkish people in US government who write about the Asia-Pacific (or now, Indo-Pacific) no longer focus on the idea of restoring American primacy. They focus instead on countering a strengthened China.

The Chinese always have denied that they intend to push the Americans out of this region. They present themselves as willing to tolerate an American presence. And if the US can tolerate something more or less like a stable deterrent balance (not just in nuclear terms, but in terms of both sides’ ability to ensure the other can’t dominate the region), if the US and China can settle into that kind of equilibrium, I don’t think most neighboring states would have a big problem accepting that. For many this might be their preferred outcome. Very few of these third parties want to face a choice between the US and China. Victor Cha’s “No Space to Hedge” chapter on Korea raises this topic. Michael Green’s chapter on Japan describes various dual concerns about not wanting to get trapped in a US-China conflict, but also not wanting the US to abandon Japan. So a situation in which a powerful-enough and present-enough US ensures China can’t simply throw its weight around probably appeals to America’s regional partners. Whether China would find that arrangement acceptable remains to be seen.

JL: I’d reinforce what Avery said about the tone shifting from maintaining American primacy, to countering China’s more assertive role, to cooperating with an expanding circle of partners. We’ve gone from prioritizing close ties with core allies to cultivating various forms of cooperation with a broad range of states. We’ve expanded the geographic range from the “Western Pacific” to the “Asia-Pacific” to the “Indo-Pacific.” That reflects an attempt to leverage the resources of many states (most recently India and the other Quad countries, Japan and Australia) alongside our own — to deter greater Chinese assertiveness, and to shore up a regional order that seems in some peril. But that agenda stops well short of a policy fully restoring or maintaining US primacy. And, of course, China reacts and responds to these moves.

The Saunders chapter suggests just how complex these interactions will be, and the somewhat perverse results they could bring. China has tried to frame what many in the region see as disturbing or assertive elements of its policy (the territorial disputes in the South and East China Seas, the heightened pressure on Taiwan, the India border issues that have heated up again) as essentially non-aggressive, non-assertive, just trying to reclaim historical Chinese territory, or to fortify China against American overreach.

Of course, not everybody buys that, which takes us back to security-dilemma dynamics, layered on top of conflicting interests. Many capacities China would develop even for quite modest purposes would also be useful if China pursued more ambitious plans in the region. As China acquires the hard power and the military capability to pressure or threaten other states, those states naturally grow wary. They have to hedge against the worst-case possibilities. That helps cement their alignment with the US — even if, as Avery noted, many regional states would prefer not to choose, or have become more skeptical about US reliability in recent years.

To close then, your own After Engagement chapter suggests that grandiose late-20th-century visions of a prosperous and globally integrated China inevitably coming to recognize the virtues of liberal democracy and responsible stakeholdership stemmed from “always-questionable expectations.” What more nuanced perspective should replace those universalizing assumptions today?

AG: First I will say that it always has irritated me when folks claim we had a consensus (among China analysts anyway, both in and out of government) that the engagement policy would produce not only a more responsible international stakeholder (in Robert Zoellick’s terms), but also a democratizing China.

You could say that engagement worked in part, and to some extent still does, for encouraging China to be a more responsible international actor. China has become a more responsible stakeholder in a variety of international institutions. Yet engagement hasn’t succeeded as much as once hoped, as is evident in how China has been throwing its weight around in territorial conflicts with neighbors, violating international norms of peaceful dispute resolution. On balance, this mixed record may reflect a problem with American expectations that China would simply wish to join an international order the US had created — without making waves, or insisting on changes that reflect China’s interests.

By the 2010s, as China became wealthier and more powerful, its perspective on such matters was more like: “Well, we do want to participate responsibly, but within a system we have some say in crafting.” And were I asked, I’d recommend that the Biden administration and future administrations figure out ways of encouraging China to keep recognizing its stake in the current international order, and pressing for updates to this order that the US and other major parties can accept. I’d hope that China’s leaders continue to appreciate how much their country stands to lose if they choose to fundamentally disrupt the current international order, and the basic approaches to global governance that it reflects. My broadest hope, one I consider firmly rooted in the tenets of realism, is that both the US and China will also realize that even with their disagreements, and despite each country’s dissatisfaction with aspects of the current international order, the enormous costs of more overt conflict (not just military conflict, but economic conflict and technological decoupling as well) provide a self-interest in figuring out ways to avoid escalating tensions — and when that’s not possible, to resolve their disputes peacefully.

JL: As Avery suggests, many people who know a fair amount about China never expected engagement to operate as a magic cure-all. Their more modest version of constructive engagement didn’t involve changing China domestically, so much as steering China towards integration into the international status quo of rules and institutions.

We’ve now reached a point where many see constructive engagement as having failed, or starting to fail. Going forward, it seems clear that shifting perspectives on Chinese ambitions, and shifting perceptions of China’s external behavior, have ended any consensus around constructive engagement. We titled this book After Engagement to reflect the fact of those days being behind us. But no new consensus exists about what kind of approach should or will come next. Overwrought perspectives would argue that a new Cold War has begun or has become inevitable, with China seeking to export and implant its autocratic model in the region and around the world. Not to say this couldn’t happen, but Avery and I consider it a stretch to assume we’re definitely on that path. We have a more cautious or modestly pessimistic view: that whether as a matter of ideological commitment and policy design, or as a consequence of complex domestic and regional dynamics, China will pursue certain agendas with the likely consequence of subverting some aspects of the rules-based international order the US long has supported — but which the US has not done much to maintain, or update and improve, in recent years.

Given that we find ourselves in a time “after engagement,” without any new consensus, I, like Avery, would hope for both countries’ foreign-policy circles to recognize that the current international system, for all its flaws, still works better for China and the US and their publics than the alternative of letting this existing order fall apart, or bifurcate into spheres led by China and the US. That’s a messy and perhaps unsatisfying conclusion, but one that seems fitting for this moment, as calls for decoupling grow louder and perceptions of an adversarial relationship can take on an air of inevitability. The US and China will have genuinely conflicting interests, and there will be areas where the two disagree and pursue opposing goals, and look like leaders of separate camps. But there are also areas of common interest, where the US and China should compromise and collaborate when we can. The tricky question then becomes: how much can we build out from cooperation in specific areas, to improve the overall relationship (to our mutual benefit, and to the world’s benefit)? How much will we run the risk of getting caught in some quite toxic cross-issue tradeoffs? How would the US handle, for example, a call from China to yield a little on Taiwan if China cooperates more on technology issues — or something like that?

We’ll also of course see recurring and novel and unexpected issues cropping up. So how will the US and China deal with all of these old and new challenges, now that the era of constructive engagement is over? That’s a question the authors address in this book, and that we’ve tried to tackle in this conversation today.