Lucinda Rosenfeld is the author of five novels, most recently Class (2017). Her stories have appeared in Harper’s, N+1, and The New Yorker.

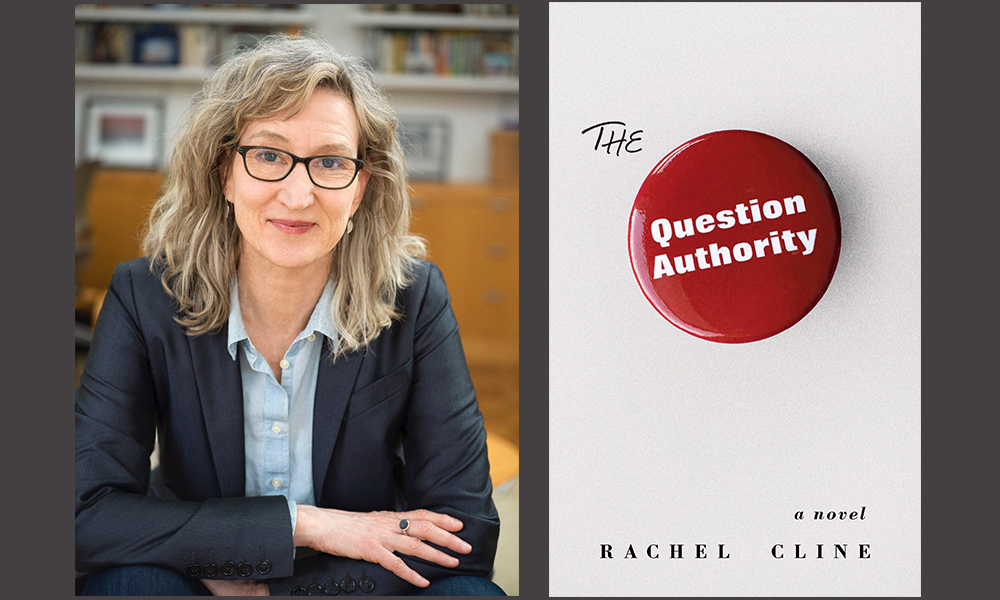

Rachel Cline is the author of the novels What to Keep (2004) and My Liar (2008). She has been a film and television writer, a content strategist, and, since 2009, a civil servant. She lives in Brooklyn, New York, a few blocks from where she grew up. Her newest novel, The Question Authority, publishes April 18, 2019.

¤

LUCINDA ROSENFELD: The Question Authority is inspired by on your own experience 45 years ago at a hippie private school in Brooklyn, where your middle school English teacher was initiating his 13-year old female students into sex — even more insanely, with the participation and consent of his wife. Was is it a coincidence that you wrote this book at the same moment that the culture at large was beginning a more serious conversation about sexual assault, harassment, and the abuse of power (usually but not exclusively by older males in positions of authority over younger females.) Or did it simply take you a half century to process and figure out how to work the material into novel form — and if so, why do you think that is?

RACHEL CLINE: “Half a century” sounds a little alarming, but I think it takes decades to untangle this stuff. The decisions you made at the ages of 15, 25, 30 start to take on different shadows when you’re old enough to see your own recurrent patterns. Your own recent story, “Sick Puppy,” does a brilliant job of looking at a young woman’s participation in her own seduction by an authority figure, and how she reframes the experience as she gets older. My novel is as much about that — the untangling and reframing — as it is about the initial injuries. My protagonist Nora’s difficulties as an adult may be set in motion by her teacher’s “messing with her mind,” or by her sense of having been betrayed by her best friend, but they are also attributable to her family background, her relationship with her mother, and her own intrinsic character.

By any modern measure, a 26-year-old man sleeping with a 13-year-old is a grotesquerie. Yet I appreciate the way you refuse to paint Beth, the main character’s best friend and one of Bob’s (the pedophile teacher’s) middle school “lovers,” as a completely wide-eyed naif. Even if she is too young to understand what she is getting herself into, Beth is clearly precocious, sexually and otherwise, and also vocal about her quest for experience. At the same time, and without giving the ending away, you don’t shy away from suggesting that Bob’s actions have a detrimental lifelong impact on Beth and that she is never fully able to escape his clutches. Can you speak to this balancing act and how you came to understand Beth as a character? Based on our earlier conversation, I know that the you lost touch decades ago with the real-life model for her.

As I worked my way through the drafts of this book, the one thing that was a constant was that I wanted to give the girls some agency. I remember just despising the mythology around “girlhood” when I was young: the pink ribbons and fluffy, lacy crap; the dorky, idealized romances in the books we were supposed to like; the sexless, pretty-boy teen idols — it all made me furious. The girls I grew up with were brave, adventurous, and determined to experience life — like my character Beth. She is, as you mention, based on my best friend from grade school, whom I haven’t seen since the 1970s. So the character Beth is a composite of every future life I ever imagined for that lost friend.

At one point in the writing process, I realized that I had been writing this novel in my head, all along: collecting and cataloging anecdotes, impressions, and cultural moments that were related to childhood sexuality, to pedophilia, to student-teacher relationships, to sexual exploitation and how women heal (or don’t). And my alertness to all that started in seventh grade, so some of the impressions that stuck with me were firsthand: the scene in Beth’s finished basement, where she and Nora make a pact while experimenting with Beth’s mother’s cast-off make up, is pretty much straight from memory.

The other implication in the book is that the main character, Nora, who more or less spurns Bob’s physical advances in a photo dark room, has nonetheless been unable to shake the experience of being touched and photographed by him. (The Nora character in the book has struggled in her adult romantic relationships.) Do you think there is something intrinsic to student-teacher relationships and particularly student-English teacher relationships which render even less egregious violations destabilizing in some profoundly corrosive way?

Absolutely. As an adolescent and young adult, when you are first learning to read and write beyond basic competence, you are uniquely vulnerable in that one realm — the voice in your head and the things it tells you about the truth of the world. You may look a lot like a grown up, and your body may be fully formed, and you may even be legal to marry with your parents’ permission in many US states, but the place where you are still underdeveloped is the place where you engage with reading and writing. One of the techniques Bob uses to get into the girls’ heads (and pants) is having them keep a daily journal that he periodically collects, reads, and comments on. This is something my own former teacher also did, and his marginal notes got past my very well developed defenses in a way that continues to amaze and alarm me. I can still picture his handwriting, see the words, hear the tone of his snark. I gave that experience to one of my characters, as well.

The book gives voice to different characters, including Bob himself, whose letters to his wife are sprinkled throughout the text. In Lolita, Nabokov famously turned Humbert into a sympathetic character. While writing The Question Authority, were you able to empathize with Bob at all, and, if so, on what grounds?

I think so, but I’m not sure readers will be able to get there — as with Humbert, it’s a tough sell. The thing is, on some level, I really do get it: girls at that age are maddeningly attractive — and I think that’s nature at work. Don’t forget, for most of human history, we became wives and mothers as soon as we matured sexually (or sooner). Bob, at 26, is also profoundly immature, so the mental gap between him and his students is not that large, and he’s also in the grips of the 1960s outlaw-hero myth. But he does catch on, as he gets older, to the harm he’s done — because it winds up having implications for his own children. I also try to show that he is capable of genuine love — for his kids, his second wife, maybe even his first. He’s a mess, and a monster, but to me he’s also very human.

Talk to me about the title. I recall seeing those “question authority” buttons on jean jackets back in the day. Why the “the”?

Nora sees the button (without the “the”) on Bob and misunderstands it. She thinks “question” is a noun, and so she interprets the button to mean that Bob is declaring himself the authority on all questions (and their answers). That would be in character for him. Of course, she herself becomes an expert at questioning, as an adult, so there’s that in there, too.