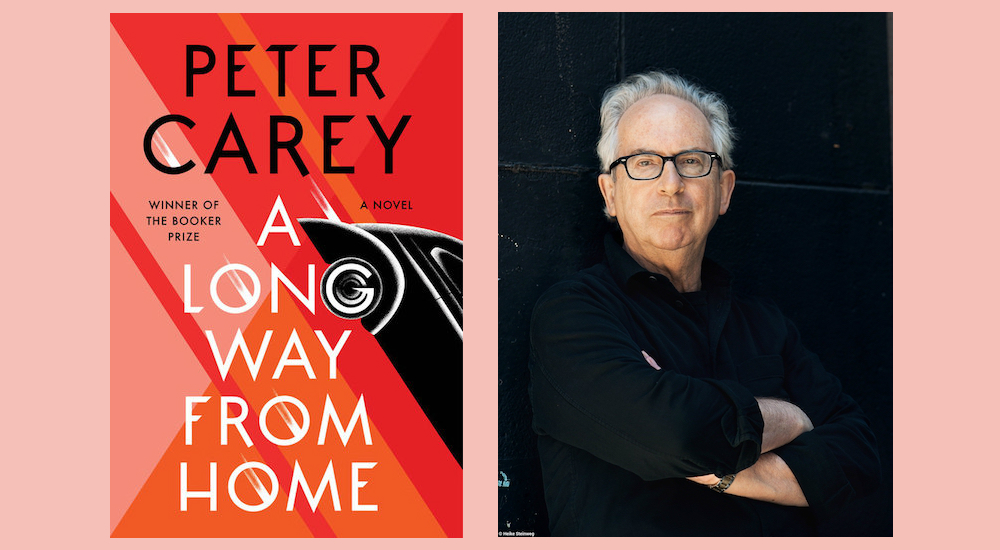

Peter Carey is Australia’s most decorated international novelist. His first book, The Fat Man in History, was published in 1974, and his work has often touched on themes of fact and fiction, history, and the arts. Two-time winner of the Man Booker Prize, three-time awardee of the Miles Franklin Award, and an Order of Australia, Carey is routinely cited as a potential Nobel Prize for Literature Winner. He currently lives in New York City and has recently released A Long Way from Home.

¤

ROBERT WOOD: You have just released a new novel, A Long Way from Home. Tell us about the book — how did you come to write it and what is its narrative?

PETER CAREY: At its heart are two sets of maps of Australia, the first determined by a 1950s car race around Australia. It was actually a “Reliability Trial” but I say “race” because it is the fastest way to understand 250 lunatics on a 10,000 mile course that circumnavigated the country, much of it on tracks, that would break a stock-standard production car in half. This, the Redex Trial, can also be understood as map-making by white people pissing on the borders of their conquered territory, an act of territorial occupation made in ignorance of the 50,000 years of previous occupation. Aboriginal people had no part in the hugely celebratory media coverage of the Redex which consumed the country like a football final in a sports-mad city. This was a luminous part of my childhood. I fondly remember the muddy beat-up cars coming through my little town at two in the morning.

That is a sentimental white memory, involving my family who had a GM dealership in a town of 5,000. I grew up, not with literature, but the smell of gas and fan belts and the long hum of parental conversation about … cars, what else was there? All around us, if course, was the land Aboriginals had once called their own. We never spoke or thought about them. The only Aboriginals we saw were on postage stamps.

A lifetime later, at home in New York City, I found old newsreels of the Redex Trial on YouTube. When I saw that Peugeot 203 in the cloud of outback dust, I thought “you guys wouldn’t know if you were driving up the aisle of a cathedral.” And, given the Aboriginal relationship with land and place, it’s quite likely that dusty track cut through sacred territory. Those Redex strip maps must have intersected many ancient Aboriginal song lines, lines of story, ritual, myth. Pedagogical lines as well. Surely, I thought, years later, the Rainbow Serpent might pursue its ancient path right through that gas station.

And there I was, at the start of a new book in which I might hope to address the single most important aspect of Australia: our white denial that the land was stolen.

When I begin a novel I don’t yet know the characters, and while I can have a clear idea of a journey and what it means and where it will end, that is not the same thing as knowing the story in advance. What I look for, and what Redex gave me, was a site of inquiry, a place I could happily spend two years and hope to come out the other end, after much anxiety, with a work of art.

Those two sets of maps gave me a chance to write an important book which would journey far beyond my present knowledge. Seeing where I was, I experienced a distinctive and oddly comforting form of vertigo.

It continues previous engagements with the “historical novel,” which includes your earlier work True History of the Kelly Gang. After all, the book does draw on real events in the past, like the Redex rally, but it inflects it as a work of fiction. Could you tell us about how you conduct research, how you weave fact and fiction, about how you comment on history as a genre?

The book is set in 1954 which makes it a historical novel for you, but not for me. A Long Way from Home is set during my lifetime. Anyway, if I am to talk about weaving fact and fiction it might be better to think of True History of the Kelly Gang, a title which I hoped would draw attention to the wobbly relationship between truth and history.

Ned Kelly was hanged in 1880. The Kellys were poor and therefore left no libraries or correspondence, not even love letters. Their huts were built from native timbers and were destroyed by fire or termites and then, finally, by souveniring tourists looking for relics of a national hero. The only written records are court records, police accounts, his own Jerilderie letter (the DNA for the voice in the novel) and contemporary newspaper accounts.

When I think of this history I imagine a vast stage in darkness with a few narrow spotlights illuminating moments that have been recorded and sometimes authenticated. The darkness is my natural territory. Here I can imagine all the characters, all the unrecorded exchanges, the passions that lead Ned to walk through that particular door, into those brightly lit places where he will fight Wild Wright, pick up that gun, construct armour from ploughshares. All these I know I must respect. But I can construct possibilities in the darkness. I think in equations: if this is true, therefore it follows that. For instance, if Ned and his mother were a bonded pair (as history insists) what does that mean in every day life? Following this sort of logic, I imagine what has never been written about, not only Ned and his mother but, for instance, the fate of Irish folk custom transported to the wrong seasons in a different hemisphere. I am not rewriting history so much as interviewing it. It is a conversation most of all.

But you asked about research as it applied to A Long Way from Home. This was also a continual conversation, with books, of course, obsessively, continually, but also with their authors, with oral histories, anthropologists, rally car drivers, car dealers, and also, most excitingly with Aboriginal people and their working allies. I used telephone, email, aeroplane and rental cars. In this long congenial process other people rewrote my pidgin dialogue, and I was able to incorporate a bitter funny Captain Cook Saga as told to tape by the late Hobbles Danaiyarri (which might well stand as a companion piece to all those statues of Cook.) My penultimate draft was read by Aboriginal readers where to my embarrassment, it was pointed out that I had spelt Aboriginal with a lowercase a.

One of the interesting aspects here too, is that this is a post-nationalist, or even post-national work of fiction, with characters who are unseen by this gaze. Can you comment on how the idea of the local and the global circumvent national concerns even as it is grounded in “Australianness”?

Colonialism was, of course, a global endeavour. We are living in a time where the trauma is surfacing in places where it has hitherto been denied by colonizers and their beneficiaries. I mean that the rapacious nature of the enterprise, its murderous operation, its environmental destruction, and its falsification of history are emerging all over the world.

Traveling recently, I saw how the novel connected to readers in United States, Canada and Ireland where the atrocities of colonialism are neither forgotten nor denied. No-one in Ireland ever thought I was “well-meaning” to imagine history through the eyes of the victims. (Of course, it is uncomfortable to wake up with blood on our white hands. What are we meant to do now?)

You have been known as a formally inventive writer throughout your career, including playing with the fable, even the magical realist, in The Fat Man in History. How did you settle on the form that you did with A Long Way from Home?

The form is decided by the needs of the story. The map of the Redex trial determines it. So does the fork in the road as we veer from the white road to Aboriginal. Some reviewers seem to imagine it was a last minute decision. In fact, it was the one element of the book that was locked in place from the moment of conception.

How does this form inflect its politics? Could you comment on how this matters for contemporary discussions of identity, belonging, and place with reference to settlement and whiteness?

The swerve is the form. The form is the politics. The form takes Willie to self-knowledge, Irene to confront the cost of whiteness. If “form” also describes my decision to tell the story in two voices, we see an argument for the author to inhabit the point of view and feelings of others. To me this is the reason novelists exist, to make well-shaped works of empathy, to imagine what it is to be someone else. Can a man convincingly write in the voice of a woman? I leave that to my female readers to decide.

Situating that conversation now in light of what is happening more broadly, from the rise of strongmen in the Philippines to India to America as well as ongoing questions of mass surveillance, media freedom, can you speak about the role of the novel as a way of raising consciousness? Of it as a way to educate people?

I began to write imagining that I might change consciousness. That was over 50 years ago and if I still write with that hope, although I think more in terms of Conrad Lorenz’s butterfly effect, which means there is some chance that the draft from my fluttering wings will, with luck, create a tornado. There is a greater chance, of course that I will be struck by lightning.

Just the same, I was surprised and pleased to discover, amongst recent audiences in Australia, some sign that the novel (its humor most of all) seemed to permit a less frightened, more open, conversation about race.