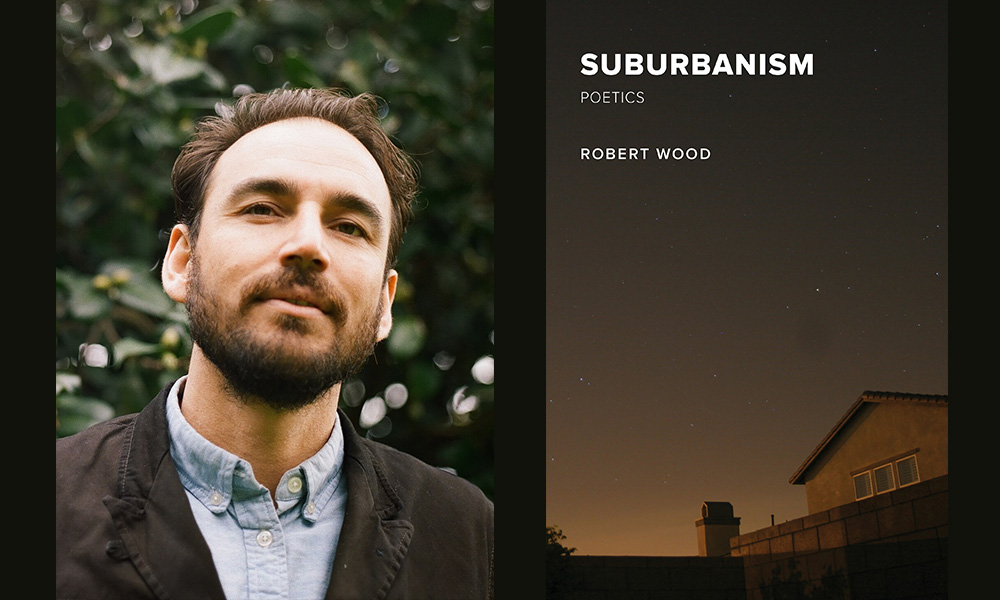

Robert Wood’s new book of essays, Suburbanism, is an exploration and interrogation of a middle ground between city and country, of suburbia as poetics — a liminal consciousness inherent to the suburbs. In my opportunity to speak with Robert about his new book, he enlightens, expands, and invites readers to understand suburbia far beyond a clichéd, cynical view. He also provides a look inside the process of gathering inspiration not only from other poets and philosophers, but from the daily wonders of living a suburban life.

Robert Wood is the Creative Director of The Centre for Stories and the Chair of PEN Perth. He has lived in cities in the United States, India, and Australia, but now resides in his hometown of Perth. Robert is the author of two previous books, History and the Poet and Concerning a Farm. His archive is housed at the Kislak Special Collections Library at his alma mater, the University of Pennsylvania.

¤

MITCHELL EVENSON: In the opening pages of this book, you state “it will take me years to realise that home is not a place at all, but a practice and a hope and a possibility that always grows.” I think that word practice is really key to what you are proposing — a poetics is about practice, about living it, not just thinking it. How do you apply these poetics in your life right now?

ROBERT WOOD: Living a poetics does mean thinking it, and then forgetting it, and then getting it in a distinct way. It is a poetics that is a bridge to life, which has been crossed but not forgotten by the child who climbed the ladder and sent their owl off at dusk.

In terms of my daily practice, I wake up, drink tea, walk to work, learn and teach, come home, cook, read, and sleep. I walk my ten thousand steps and think of the ten thousand things. I pay attention to the conversations I have with my wife, family, friends, colleagues, and strangers. I try to apply the best part of the poetics in Suburbanism to my sensibility, lifestyle, rituals in all these small interactions that accumulate into minutes, hours, days. That is what makes a life.

In the conversations you’ve had about your work on suburbanism, do you feel that poets tend to be more or less receptive than others to the idea of poetics as practice?

There are poets, and then there are poets. They change from one to the other and from day to day. They receive and give as they can.

Perhaps being defined as a poet is about one’s relationship to language, but other people have a poetic practice when it comes to building, baking, or being. Their expressions differ, but I want to consider the language beneath the language be that nails and gyprock, self-rising flour and plain, or sitting on the porch and watching the chickens peck at grain. I mean poetic as a way to describe something that opens up yet more possibilities, of swimming in questions amidst the turtles all the way down to the limestone on the bottom of the ocean surrounded by plankton and plastics.

Here, the type of poet I am interested in is the suburbanist, an identity that represents the suburbs truly. They might go by other names, and they might not even work in language, but language is a great metaphor for thinking about practice in the world as it exists before us. As for reception, it depends on whether you can draw someone else in, someone with a family resemblance who wants to be in a conversation that is meaningful to you both. Suburbanism is the start of that for some, and it is a hinge for others that might allow us to end on a high note when the time comes. The question is then: how does the suburbanist become an Old Master?

You spend time addressing the cynic’s counter-argument directly, noting that, “to the critic, suburbia seems to be a vast, elaborate, cruel system made up of individuals who are atomised, isolated, anonymous parts of a dull, monotonous, conformist machine.” Did you ever see the suburbs as the critic does? If so, when and how did your understanding of suburbia change?

Growing up, I internalized a popular intellectual narrative about the failures of suburbia. This was the case even as my life there seemed different to this hegemonic representation, and the people I knew there felt themselves to be happy. Coming home has been a gradual realization in the possibilities that were unique to me, and hence, what may exist in suburbia.

I think it is common to resist, critique, and take down as opposed to build. I wanted to create a resilient, empathetic, soft system that the collective can engage with. I write then with the suburbanite critic in mind, the person who negates me in a fundamental sense. Suburbanism carries a hope that they might change their habits and come into a truer consciousness. From that, and after unsettlement, we might come to rest in nesting. In thinking about identity too, I could have reached for my Malayali heritage and found succor in a type of ethnic notion like Négritude for the third millennium. But to me, I am also connected to other bodies politic, which could lead one to hybridity. That too was not enough. As a result, I turned to the commodities, social relations, status groups around me, and that meant thinking about the construction of “the suburban.” This was one frame that enabled me to reach out intersectionally, by acknowledging my class and race and gender and privilege and place, and so I arrived at “lifestyle” as the aesthetic, materialist, and spiritual expression of suburbia and beyond. This was about a contemporary consciousness that emerged from it.

There were also moments of intense visions about the suburbs around me, about how to write through to the critic, to translate between gods and people and animals, and to persist in the face of concrete doubt and pouring acid rain. It meant reaching back through forgotten past lives and coming up for air when one could scarcely breathe and yet somehow speak. I could not have written this book without a lot of people and the places they let me into, and it meant looking anew at what is happening from Ernakalum to Karratha to Sudbury.

The language you employ is liminal just as the suburbs are — there is an at-easeness with jumping between the material and the spiritual, the concrete and the abstract. Language is both, thus the language you use must be both, speaking of “archipelagos of language,” “a continent that grows inside us.” How did writing such liminality challenge you in your use of language to describe it?

You read, you think, you process, you think, you articulate. Liminality is a reality that I engage with, and in that way it is a kind of center, not as a third way or a negotiation or a compromise. But, like the journal Liminal itself, it is truly collaborative and allows you to turn your head in all directions to find that your neck is where the axis lies.

The move then is about archipelagos, which is to say islands, as much as it is about continents, which is to say mass; and within that it is about the internal, the external, and the mixing that happens at the border between the two.

Finding the language for Suburbanism meant going foraging where there is a rich biodiversity of language as well as an audience that appreciates what you return with. It is no use catching the bag limit of crayfish without people to share them with.* And for me, this type of liminality came from a multilingual polytheism that traveled through a number of discourses to arrive at its own dynamic place.

*For those who are interested, it is eight per pot per day where I live and a person can have two pots in the water at any one time.

One of your main goals seems to be inviting readers to re-imagine the suburbs as a place where poetry happens — a place that is inherently poetic, not just because of its liminal status, but because the people that live there and how they live are poetic. This means reading poets who engage suburbia in this way (some of whom you’ve referenced throughout the collection). Are there any specific poets you find are especially helpful in this? Any that really guided your work on this collection?

It is a very kind observation to note that this book is an invitation, and there are a number of poets that inform my welcoming. They are not necessarily the ones that are written about in Suburbanism. As a spine of my thought, I would have to cite Carl von Brandenstein and AP Thomas’s collection Tarruru, which introduced me to Donald Norman and Robert Churnside, whose work I have heard since then as it was spoken and sung. Then there is John Minford’s Tao Te Ching, Emily Wilson’s Odyssey, and Ranjit Hoskote’s I, Lalla, all of whom have featured in great interviews on LARB. And there are poets I interact with on a daily basis in my work at The Centre for Stories. All of these have guided the work as much as the contemporary ones that I write about in Suburbanism itself.

But, there is also philosophy because it is a work of poetics and that stretches from Horace to Boccaccio, Weber to Wittgenstein. I think here, it is also about reconciling myself to linguistics geographies that are nearby, and I think of Charles Darwin on Albany, which he detested, and Karl Marx on the Swan River Colony, where he saw that our social relations were distinct. They are both close to home and, in some way, I am speaking back to them most of all.

And finally, there are the people in my life that are poetic without writing a sonnet, pantoum, or tjabi at all. They might be art historians or curators or administrators, but in them I see the poetic possibilities that come with being alive to the world as a whole. They are the ones I am silent for because I cannot speak in their presence. I am listening to what they have to say as they draw breath and reflect.

Structurally, this collection of essays spans various styles and subject matter, at once applying Hegelian philosophy to suburbanist theory, then reflecting on your personal history, and even using parable to illustrate what it is to live with a world spirit and find “home.” How did you come to your organisation of this collection? And how do you hope your personal reflections on “home” will inform the reader?

The Hegelian idea I use the most in here is “dissemblance,” and that is a specific response to the misreadings of deconstruction, which still seem to be popular despite the abundance of rhizomes that have somewhat taken its place. But, Weber’s idea of “lifestyle” matters as a response to both class and identity politics; and in Wittgenstein’s “family resemblance” I find a way to speak back to “Othering.”

To return only to Hegel though, in writing this book, I read Philosophy of Spirit every day at work for six weeks during a residency at Columbia University in 2017-2018. That informed Suburbanism as much as eating in diners and wearing jeans and visiting galleries across the park from me. But, I first became interested in Hegel in graduate school in 2006, and I always remember a passage from his Lectures on World History. In it, he states that “the Indian has no history.” Of course, I felt a personal affront as a person of Indian origin studying history, and that may have given rise to a post-colonial reality. From that, however, I began to think of the nation, not of whether I was Indian or not, but rather what other nations could claim me as well? I also thought about how to define history, or rather, what does Hegel mean in a common-sense way with this phrase? And so it was not necessarily about finding home in a nation, or a definition, or even the past. It was not even about negating what is established.

Rather, it was about cultivating a daily practice that led me to tarruru at every sunset no matter where I was, and allowing that to grow over the course of a long and happy life. And in that, it was about seeing whether it was possible where I had grown up, in those suburbs where my idea of place had congealed so much that it was calcified in its core. I felt if I could make it there, I could make it everywhere. What would it take working together to retrofit our deep selves in a way that was an example to others?

From that, the aim of my first book, History and the Poet, became clear once again in a place I am still learning about – to know myself, to live a good life, to change the world. And that was where home was, in the comfort of this reality, which the reader can learn from too by picking up Suburbanism and giving it a go.

Photo of Robert Wood: Leah Jing McIntosh.