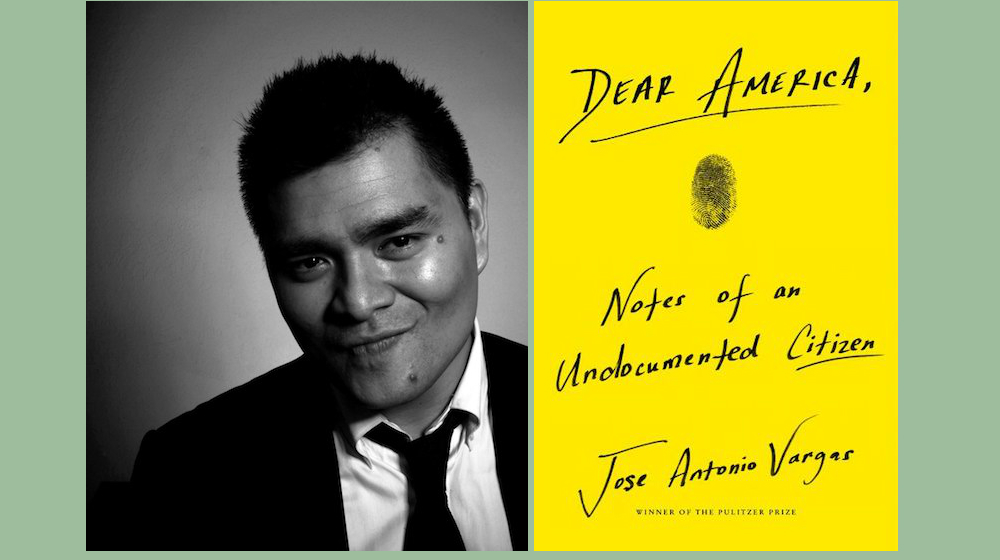

How to start changing “the politics of immigration” by changing “the culture in which immigrants are seen”? How to publicly present one’s lived experience as “a person whose body was not supposed to be here”? When I want to ask such questions, I pose them to Jose Antonio Vargas. This present conversation (transcribed by Christopher Raguz) focuses on Vargas’s memoir Dear America: Notes of an Undocumented Citizen. Vargas is a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist, an Emmy-nominated filmmaker, and a leading voice for the human rights of immigrants. Vargas founded Define American, a nonprofit media and culture organization designed to combat anti-immigrant agendas through the power of storytelling. In 2011, the New York Times Magazine published Vargas’s groundbreaking essay chronicling his life in America as an undocumented immigrant. A year later, Vargas appeared on the cover of TIME magazine worldwide with fellow undocumented immigrants, as part of his follow-up cover story. His subsequent feature film Documented received a 2015 NAACP Image Award nomination for Outstanding Documentary.

¤

ANDY FITCH: I very much appreciate Define American’s stated mission to leverage a wide range of personal narratives “to influence how news and entertainment media portray immigrants, both documented and undocumented.” So could we here introduce your own personal autobiographical story by looking back at your New York Times Magazine piece, and how responses to that piece, even from some fellow journalists, “represented the inability of the agenda-setting news media to understand the broader issue of immigration and the millions of people…directly affected by it”? Which most basic elements of the story you told then, and the story you tell now, speak most directly to your ongoing call for “this country of countries, founded on the freedom of movement,” to look itself in the mirror much more “clearly and carefully, before determining the price and cost of who gets to be an American in a globalized and interconnected 21st century”?

Jose Antonio Vargas: You know, what has transpired between 2011 and 2018 feels like this whole new era in American history. And for me, from the very beginning, I’ve faced that basic question of: how do you humanize this? How might journalists like myself frame this outside of the typical political conversation? For as long as I’ve lived in America, and certainly for as long as I’ve worked as a journalist in America, immigration issues have been framed — with some exceptions, of course — largely through the prism of politics and policy. And we as a country absolutely have gotten more partisan, so tensions on this topic have become much more partisan. I mean, do we have independents on immigration? If so, what does that look like? And then specifically for Dear America, one journalist pointed out to me a few months ago that she kept looking for the phrase “immigration reform” in the book but couldn’t find it. She asked if that was deliberate. I said: “Definitely. I want to talk about these issues outside the US vernacular of politics and policy and partisanship.”

I mean, since arriving in this country, and maybe especially given my first name, I’ve been led to believe that this issue basically is about one particular border, one particular wall. The hardest things to write in this book were the shortest chapters. I overwrite, which probably comes from reading the New Yorker so much from such an early age. But the chapter about the Bracero program with Mexico is like, what, two pages long? I wanted it to interrogate how “illegal” immigration came about in the first place, and how the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act really kind of changed the conversation.

Writing about immigration outside of the typical “Mexicans crossing the border” narrative seemed really important — and here of course recognizing that this issue has gotten so racialized, with everybody acting like undocumented immigration only happens with Mexicans and other Latinos. That’s why writing about growing up as a kid in the Philippines felt necessary, even though I had a hard time doing it, because I really just didn’t remember. And of course the journalist in me felt this need to really remember it right. I kept basically reporting out that day I’d left the Philippines, and then realizing that an objective report on the experience of a 12-year-old basically snatched from his bed just didn’t feel organic. I woke up, I went to the airport, my mom handed me a jacket, and off I went. And all I can remember is how many islands I saw below. I’d never really grasped the Philippines as this country of islands until I got up there and looked down at everything.

Still, writing from this very specific perspective as a journalist has trained me to stay so hyper-focused and hyper-aware of everyone around me — until I myself almost become invisible in the process. That actually made journalism in many ways the perfect career for me, because I could just slip right in and disappear. I’ve had so many moments in my career of just being in the room where I wasn’t supposed to be. I mean, I’d just carry around a backpack when reporting on the 2008 campaign, and everybody thought I was an intern, right? That got me into so many places.

Toni Morrison actually comes in for me here. She played a really important part in my writing Dear America. She gave a quote in an interview that I had typed at the very top of my computer while writing this book, something like: “I stood at the border, stood at the edge, and claimed it as central. And let the rest of the world move over to where I was.” For me that meant: how do I write about myself and my experience without feeling like I have to justify my existence to other people? And undergoing that process somehow took me all the way to the point in the book where I say: “Home is not something I should have to earn.”

Sure Dear America’s prologue explicitly announces that this book’s core is “not about immigration at all,” but about a less conventional conception of homelessness. Or “immigration” might imply a one-way, one-time resettlement project, whereas your “Purgatory” chapter sketches this condensed self-portrait: “because I’ve never had a real home, I’ve organized my life…constantly on the move and on the go, existing everywhere and nowhere.” Here I find especially poignant that, after tracing one of this country’s most prominent coming-out narratives from the past decade, Dear America closes still in “Hiding.” I find moving your retrospective attempts to understand this lived experience of having searched for some secure stable life by compartmentalizing in so many ways, until you yourself can’t help feeling crowded out by all of these interlocking but unacknowledged legal / professional / emotional connections and deceptions and dislocations. So anyway, no doubt some readers might find it intolerable to present “homelessness” as one’s allegorical station in life. But why did you consider it most instructive to place this book’s lying-passing-hiding trajectory under that broader concept of homelessness?

Well first I do mean that, at a very basic level, I started thinking about and writing the book when I really did not have a home. I’d moved out of this downtown L.A. apartment, and put everything in storage, and started living out of a suitcase. I had keys to like five friends’ apartments. I literally finished this book while staying in a friend’s living room in Bushwick. She didn’t have a spare bedroom, so I just slept on the couch.

And I actually found it useful to write this book without a physical home, and to acknowledge that part of my experience. “Hiding” comes into play here also. I’d deluded myself into thinking of home as a physical space. I finally had this 2000-square-foot apartment all to myself, and of course with all my Filipino relatives…I don’t know if you know anything about Filipinos, but we have these huge-ass families, with relatives always coming and staying with you. So I finally had this kind of dream home, and just got so depressed, just wanted to escape from surrounding myself with all these material things, because when you assimilate into America you assimilate into capitalism and consumerism. So in order to talk about my own personal history, I felt the need to introduce this different concept of psychological homelessness, which also came out of me growing up seeing so much homelessness in the Bay Area. Though of course I do want to make a distinction between homeless people and this idea of being psychologically homeless.

And that’s why, as you pointed out, this book closes on “Hiding.” As I started to make sense of my life and to structure my narrative for this book, I realized how long I’d been hiding in plain sight. I mean I’d known I was hiding from the government. But I hadn’t realized I also was hiding from everybody else. I was hiding at work. I was hiding from myself in a lot of ways. I had manufactured a kind of reality that seemed not to need other people. And in the moments when I did end up telling people about my situation, I almost felt like I was burdening them — with something I didn’t even understand myself. So after all of these confusing years and all these people I myself confused, I made a conscious effort to really name everybody in this book. Just last night for instance I talked to Pat Hyland, my high-school principal, who now happens to chair the Define American board. And for as long as I’ve known Pat Hyland, she has been trying to take care of me, trying to help me figure out how to solve this thing we can’t solve.

So I wanted to use all of that. I have to tell you: I’d never gotten therapy before. I just haven’t. But this book became the best therapy I could possibly give myself. I make so much more sense to myself after writing this book, and I’ve been astonished hearing from people I’ve been really close to since middle school who are like: “I finally feel I got to know you.”

Well pivoting back to you feeling like you’d burdened people when you told them your story, I also should have acknowledged from the start that when you describe Dear America as “not a book about the politics of immigration,” I partially don’t believe you — most broadly because I see you tapping two of American literature’s best-established genres of personal-as-political narrative. Gay coming-out narratives obviously provide one compelling example. And another, slightly less obvious point of reference comes (for me at least) from the narratives of former slaves. Just to place Dear America alongside, say, The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass for one quick comparison: the ways in which a sense of clandestine identity gets formed through reading and writing, the fugitive progression for the narrator from a way of passing (again through writing) to a way of being, the cascading self-questioning (“Can I get a ‘real’ green card? Is a ‘real’ green card something you can buy? For how much? Where? Can I tell my friends about this? Can I trust my family? Who can I trust?”), the ever-widening implication of others within what Cory Booker might call a conspiracy of love (with, as you say, nobody passing alone, with tens of millions of Americans needing to take part), the escalating necessity not just to circumvent the law but to question its unspoken premises of legitimacy and authority (“I had to interrogate how laws are created, how illegality must be seen through the prism of who is defining what is legal for whom”), the narrative arc in which one’s very successes within a stifling social system eventually require some dramatic new form of self-assertion (and as an exemplary protagonist-citizen, rather than as some secretive or marginalized or dehumanized background bit part) all echo from that 19th-century genre precedent to your own book. So whether or not you’ve read Douglass, whether or not you’d prefer to discuss Toni Morrison or James Baldwin or Maya Angelou here, could you speak to that political power of even the most personalized testimonial which you seem so to value?

Of course Notes of a Native Son had a big influence, which you can see in Dear America’s subtitle: Notes of an Undocumented Citizen. And you’re getting at why the Toni Morrison chapter felt so important, for kind of framing this question of what the master narrative means, and how as an individual you fight against it. And somebody definitely could argue that this book offers one long argument against the master narrative of how we define “legal” and “illegal” immigration.

I also was just fortunate as a kid. I don’t know what would have happened if Mr. Zehner in eighth grade hadn’t assigned The Bluest Eye. I try not to read reviews of Dear America, in the same way that I don’t read reviews of films I make. But of course when the New York Times published their review, people passed that around and so I read it. I mean, one of my friends just texted it to me. And the reviewer, Jennifer Szalai, said she had never read The Bluest Eye, but did so after reading Dear America. I thought: Okay, that’s the best review I ever could get.

And more broadly that connection to Frederick Douglass makes total sense to me. I cannot overstate the influence of writers who happen to be black. I like to frame it that way, because too often you know we think of African American literature, especially nonfiction, as this specialized subtopic, like maybe you can take it as an elective.

Or read it in February.

Right. But before I’d read anything else, before I read Hemingway, before I tried to understand Melville, before this whole master narrative of this straight white male…

Or mostly straight.

Before any of that, I realized and understood that African American writers had given me permission to claim myself, and create a space for myself, and to just become better.

Questions related to race also become crucial here as you describe how our narrow cultural frame for discussing US race relations sometimes still gets stuck in a stark 1950s black-white divide. So could we take the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act, which you describe as “arguably the least-known yet most significant piece of legislation that changed the racial makeup of the country,” and talk about its legacies (for example prioritizing family-based immigration, and prompting a dramatic expansion of Latino and Asian American communities, while at the same time creating “an ‘illegal immigrant’ problem where there had been none”), and how that particular 1965 law shapes your own American experience as much as any perennial black-white divide does?

Yeah that’s great, because everything I say here comes from someone not black, but not white either. And for us to discuss the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act takes a lot of unpacking. Even today, most political journalists, most journalists covering immigration, really don’t understand that act. Some people know the 1964 Civil Rights Act, right, which paved the way for the 1965 Voting Rights Act? But most people don’t know much about how the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act also reshaped this country, specifically in terms of Latino and Asian immigration, and also creating this new idea of calling some people “illegal.” And when you look at all of that, you realize how long this issue has been a bipartisan mess. You realize you can’t just point your finger at Republicans or Democrats. You have to look at both of them.

Similarly, you can’t just start by discussing some contemporary immigration-reform campaign. You need to put all of this within the context of US history — with these fundamental questions of who gets defined as “white,” and why whiteness comes about to begin with (which of course created blackness). And then where do Latinos and Asians and mixed-race people fit into this equation? I’ve been really grappling with that phrase “people of color,” for example, because being black and being not black but still a “person of color” seem pretty different. And then where do white people fit in or out of that construction? Isn’t white a color?

Here again, in terms of questions that whiteness raises, could we also include our totally bizarre (white-imposed) broader racial designations, whereby, for instance, some intrinsic identity supposedly binds people from India and China and the Philippines as “Asians,” much more than any such force binds Mexican and US citizens as “North Americans” or just “Americans”?

Isn’t the world, then, like 65% Asian? Isn’t it a delusion to fit all of these different Indian and Chinese and Japanese people, with their long histories and conflicts and rich cultures, into one generic category? We forget, by the way, that the US is still relatively young.

And this very America-centric point of view actually limits all of us. In Dear America I write about discovering this concept of being “Asian,” which was such a mystery to me. Right now, people are reading the book and taking pictures of the parts they like. Young readers, in particular, are sending me the best private messages or just tagging me on Instagram or wherever. I’ve found that so many non-white / non-black people, so many Latino and Asian people, gravitate towards questions about where we fit in these white-black discussions.

And you’re right about this really narrow vision of America as somehow separate, or of North America as somehow separate. What does that say about Central America? What does it say about South America? My own geographical understanding of the world basically comes out of the Miss Universe pageant. That literally got me to memorize the various countries and world capitals. But then coming into this country as a middle-schooler and trying to understand this dominant binary just felt so confusing — especially with, as the book also notes, all of these white people in my community really helping to raise me. At the same time, at the library, I’d read whatever I could find by Toni Morrison or James Baldwin, which felt like this gateway for trying to figure out where I fit as a person whose body was not supposed to be here.

Well again in terms of proactively assembling “the many parts that make each of us whole,” gay identity emerges as crucial to Dear America’s “I,” even if a less sustained point of focus throughout the book. Here could we pause on one particularly powerful formulation (“Since I didn’t know who to talk to, or what to do, or how to think about the ‘illegal’ part of me, embracing the gay part kept me alive”), and could you give some additional narrative on how your experiences as a gay undocumented immigrant (and as an individual encountering not just “external” legal constraints, but “internal” judgment from one’s own at times homophobic culture) shape the lived pulse and the analytic perspective of Dear America?

Yeah one thing I did before I started writing was reread every book I love. And one of them was A Single Man, in which gay identity is central. And as someone who wears multiple identities, I could have called my own book something like “The Two Closets.” I could have lingered even more on parallels between coming out as undocumented and coming out as gay. Maybe that even would have made the book more commercial. But I sensed that we have so much more writing about gay identity, so I wanted to write a book by somebody gay, but with gay identity not necessarily central to the narrative. I do think though that me coming out as gay pretty early in life forced me to internalize what being othered felt like, and how to protect myself from people.

Or as someone who wears multiple identities, people like to cut you into pieces. I can’t tell you how many people have come up to me and said: “I didn’t know you were gay!” Apparently I’m not gay enough. I don’t talk gay enough.

I really do still wonder what that’s all supposed to mean. Do we only have one way to be gay? For me, embracing the gay part of me actually meant embracing my individuality, and also embracing various people relating to me in all these different ways, based on how they happen to identify me. That’s why the “Coming Out” chapter comes early in this book. I didn’t want to get to the middle and only then mention being gay and having a partner and all that. I consider this identification a very empowering part of my life. And having been forced to identify as something, I always wonder about white-straight-male identity, and how it pretends not to be identifying, and how it’s so used to feeling like the center and the default. Now with everyone else empowered by their own identifications, I wonder what that does to this supposed center, this supposed default.

And here in terms of roles that Dear America’s own “I” performs, passing becomes ever more crucial, with the young immigrant Jose exuberantly cramming on American consumer culture as if some course subject to ace, and then a more anxious (self-consciously undocumented) Jose himself starting to circulate publicly as a source (if not yet a subject) of newsworthy cultural narratives. And here again passing gradually becomes less a playful form of faking it til you make it, and more a driving compulsion towards “earning the box” of a byline, towards writing such distinctive stories that no “legal” rival reporter gets displaced along the way, towards eventually facing the ironic circumstance of founding a nonprofit that provides health insurance for more than a dozen staff members while still not being able to provide for oneself. So passing definitely has guilty, fraught, pained connotations here. But as you go through all these hyper-productive stages of passing, you also formulate a compelling notion of “citizenship of participation,” of citizenship as “showing up.” For me, this embodied “citizenship of participation” ultimately enacts Dear America’s most profound form of passing — not just catching the pop-song references, but fulfilling the American credo, the Tocquevillian project of empowered and empowering participatory democracy. So could you describe what all Americans, documented as well as undocumented, stand to gain by passing the test of performing this citizenship of participation?

Alright. Great. Now we’re getting at the really deep stuff. This, to me, is the conversation. I mean, I did not take lightly putting the word “citizen” on this book’s cover. I consider this a crucial question not just of who gets called a citizen, but of what constitutes citizenship. But before I get to that I want to address your observation about passing. As you probably noticed, “Passing” is the longest section in this book. Again that all nods back to these questions about constructing “American” and constructing manhood and who gets to pass. This brings up all these historical topics like, you know, the Irish Potato Famine, and who does or does not become “white,” and which gay people can pass, and which women can perform which roles in public, and how race can fracture the women’s-rights movement, and how various feminists try to understand all of that. You could argue that the arc of American history focuses on this basic question of the journeys various people undertake as they try to pass. Like I recently got obsessed with how all of these Jewish immigrants moved to this country and Americanized their names. I knew a bit of that history, but not much, and it fascinated me how that anticipates first- and second-generation Latinos and Asians giving themselves or getting these Americanized names. Again that shows passing being this really important part of the plot throughout American history. And I wanted my own book’s “Passing” section to connect to that ongoing American experiment. And that gets us to a citizenship of participation.

First I don’t consider it an accident that Donald Trump picked immigration as his campaign’s central issue. I won’t consider it accidental if his reelection campaign focuses on ending birthright citizenship. But I also do believe that we all need to rethink who gets to call themselves an American citizen, who gets to pronounce themselves worthy of US citizenship.

Given our history with class and race and gender, and all of the othering that has taken place, and this master narrative that has divided us as a country, I don’t know if, historically, we can think of this contemporary moment as our most divisive moment. I mean, they didn’t have social media back then [Laughter]. But in terms of what now can unite us, I find that conversation really lacking. I feel that we need to clarify what America can offer its people. Of course it’s easier to tell voters what their country opposes and what they should defend themselves against. It’s a lot harder to tell people what their country commits itself to and why. And I want a country where we really feel accountable to each other, where participation in American democracy goes far beyond what you buy, or wear, or consume, or say online to your friends. I sense us needing to participate much more deeply in our communities, to find new depths of participation. Of course voting should be part of that, though that’s not enough by itself.

But it does shock me that, even in the 2016 presidential election, many of my uncles and aunts (all naturalized US citizens) did not vote — basically because America, for them, is where they work. That really haunted me, to see my aunt buying a Toyota Camry, buying a house, sending her kids off to school, but still just knowing this country as a worker: not really as a citizen, not really as a participant, not really as a part of this country. I sat her down one day and tried to explain that she pays all these taxes to this country, and that taxation doesn’t just mean taking away your money. It means forging a contract and building a relationship.

So when conservatives say “These immigrants don’t want to assimilate,” I often say “Wait a second. What does that mean? Assimilation into what, and accomplished how? Because if assimilation means having a Macy’s credit card, then we’re assimilated. If assimilation means building up all this consumer debt, then you can consider us assimilated.” But beyond that, when I think of the role of faith communities, the role of schools, the role of community centers, the role of senior centers…my grandmother belongs to a senior center, and she’s an active participant there, and I consider that really important.

So “passing” here also means succeeding, in the sense of assembling a fulfilling life, and a sustaining community, in fundamental ways.

Thank you for noticing that. Again, the biggest challenge with this book was how do I write about myself in such a detailed way, existing in this wider social system with this hyper-awareness, all without coming across as a journalist. How could I write in depth about my personal experience, and still get readers to relate? And I included for example the exchange with the Native American student because I appreciated that question of: “How do you talk about immigration and not talk about us?” Or I appreciated that young man e-mailing me to say: “Hey I know you’re not a US citizen, but US citizenship isn’t all it’s cracked up to be. We don’t have electricity right now in Puerto Rico.” I want those types of short, intense paragraphs to drop like bombs in this book, because those experiences felt that way to me. I mean, even if I did get US citizenship tomorrow, how would that relate to all the people who get defined as US citizens on paper, and by law, but who still don’t feel included in America?

In terms then of your personal story going public, and in some ways no longer being solely your own story to tell, I’d be curious how you address some responses I have to assume you often get. And here I’d maybe start most broadly with your prologue hinting at the endless daily dislocations and indignities undocumented residents might face: “A woman diagnosed with a brain tumor…picked up at a hospital in Fort Worth…. A father in Los Angeles…arrested in front of his US citizen daughter, whom he was driving to school…. A young woman…apprehended after speaking at a news conference against immigration raids.” Here I sense that close to 50% of Americans might respond: “Yeah, good, hopefully that serves as a deterrent to prevent others from even thinking about coming here illegally.” I sense that a more media-savvy (and sometimes truly empathic, truly ethical) case some immigration restrictionists might make here would frame your own lived struggles in the US as concrete proof that we need stricter enforcement from the start, precisely to prevent such traumatic scenarios from occurring. I can imagine some readers even taking the haunting scene of you locked up in Texas with all of those confused young boys who’ve crossed the Mexican border (all of which echoes your own bewildered state 20 years prior on a plane from the Philippines), and asking: “Why would anybody want to perpetuate, in any way, this whole cycle?” So how do you respond to such disparate perspectives on your own personal story? How might you live up to your own ideal citizenship of participation as a mode of “using your voice while making sure you hear other people around you” — not just assuming that your fellow participatory citizens should sit back passively while your narrative defines the terms of the debate for them?

Well I made a very conscious effort with that whole scene of the man on the plane who approached me and said “I didn’t know illegals fly first class.” I wanted to at least start to show how much many Americans’ perception of undocumented people gets shaped by Fox News. If Fox News had to cut back and focus on just one single issue, I have to assume they’d pick immigration. And you don’t see any real equivalent response on the left. Fox has so dominated the presentation of this issue. And my work as a journalist has trained me to ask why people think the way they think. Some of my friends actually consider this a masochistic compulsion on my part. Some of them just couldn’t understand when I started going on Fox News — because apparently we’re only supposed to de-legitimize Fox. And I responded that you might hate Fox News, and not watch Fox News, but many millions of people do watch it. And anyway, how can you hate something you don’t know?

So I just come at basically any topic from this prism of wanting to know the why and the how — even for people who want me deported or detained. I conduct my life this way. When I moved to D.C., for example, I befriended all of these Log Cabin Republicans. I’d thought that was an urban myth: gay Republicans. But somehow they become my closest friends, which I found fascinating, and which also got really complicated when I came out as undocumented. Someone really close to me actually told me I should get deported. We’d spent so much time together, but he still had that point of view. So that’s also part of Dear America’s frame of reference — living with all these perspectives which may not mirror my own.

When you mention your friendships with Log Cabin Republicans, or going on Fox News to reach audiences on the right, or when Dear America offers corrective reformulations of our fundamentally hypocritical rather than “broken” immigration system (“we do not have a broken immigration system… What we’re doing — waving a Keep Out! flag at the Mexican border while holding up a Help Wanted sign a hundred yards in — is deliberate”), I do wonder about explicit policy ramifications of the lived perspective this book presents. I wonder, for instance, how your personal experience of emotionally painful separation from your mother, of undergoing a “nightmare scenario” in your teens, of as an adult participating (understatedly, but powerfully in this book) in a remittance-fueled Philippine economy “creating a culture of consumerism and a cycle of financial dependency,” might position you in relation to arguments, both from right and left (from, in my own recent reading, both Reihan Salam at the National Review, and Andrés Manuel López Obrador in his new book), that an ethically minded US would prioritize helping to foster our international partners’ own economic growth, rather than providing opportunities for some relatively few lucky laborers to immigrate — that everybody would benefit if we could enable more such workers to stay in their native-born countries, to stabilize their families, to pay for local goods and services, to preserve and fortify distinct national cultures.

Well I don’t think we can rely on any one strategy here. We need multiple strategies. And that also means we need to ask ourselves: if you give someone in Guatemala, Honduras, the Philippines, India, Korea, Ukraine the choice to leave behind everything they know, just to come here, would they do that? I’d argue that most people would not. Meaning, I think most people would stay where their roots are. I think many people would want to stay and take care of their family, and to keep living in the communities they come from. Of course some people do make this choice to leave and pursue a life someplace where they don’t speak the language, they don’t know the culture, they don’t know how they’ll fare. But it takes a special kind of person to do that.

That’s part of what makes the American experiment so fascinating, actually. But I bet that if Mexico and the Philippines gave everybody the opportunity for economic independence in their own village or town or wherever, I think most people would stay. I asked my grandparents a lot: “Why did you leave?” I mean, I don’t know if you noticed, but Dear America’s first chapter’s first sentence says: “I come from a family of gamblers.”

I liked that.

Because I wanted to make it clear that leaving was this gamble, right? My grandparents decided to make that gamble, basically because they’re gamblers. I mean, I can picture playing cards with my grandmother and my mom for as long as I can remember.

And similarly, in my own thinking, I don’t want to close myself off from any political orientation or economic theory. I want to keep myself open, to try and figure out the best sets of circumstances and policies, so that people can live their lives with as much dignity and freedom as possible.

Sure that seems to fit your pensive, empathic argumentative style.

Thanks for saying that. Operating in our culture today, everything can seem so quick and so loud that I often can’t hear myself think. But I really appreciate the idea of “performative activism.” Even when social media asks us, begs us, demands us to keep moving quicker and getting more decisive and speaking louder, I still want to process all of this. I still want to interrogate and inquire and always make it clear that my own current opinion might need to change. I always want to show myself asking: “Okay, did I hear that side correctly? Or did I just project what I wanted to hear?”

Again, part of this comes out of where and how I grew up. This whole Republican-Democrat binary seemed to me, in many ways, as fascinating but also as confusing and sometimes narrow as the black-white divide around race. Like I remember, when I saw the movie Lincoln, having to keep reminding myself that Lincoln was Republican.

And when I really focused on writing this book, that almost felt like a meditation of sorts. Some people probably expected me to title the book Dear Trump, and to shout and to point fingers. I definitely do have that anger inside me. But even right now at this moment I see this wonderful portrait of Maya Angelou. I just moved to this place and don’t have anything on the walls yet. And Maya Angelou has this fascinating quote, basically saying: “Anger is useful. It’s a productive thing, but you have to focus it. You have to write it. You have to dance it. You have to choreograph it. You have to sing it. You have to act it.” So I’ve tried to make my anger as productive as possible, which for me means developing that pensiveness you mentioned.

So even as Dear America rightly centralizes your own lived experience, I wonder how that pensive personal approach might open up unexpected empathic channels or policy perspectives for you. My own recent thinking about immigration politics, for instance, has been shaped by talking to certain Democratic leaders who might pivot from warning of an upcoming crisis of automation-driven job displacements, to advocating for increased immigration to address future service-sector growth, without sensing how many Americans find their own precarious circumstances unaddressed by this national vision. Or even the Dear America scene with the “older South Asian woman” who ended up being an attorney, and who reprimanded you “Don’t bind legal with illegal,” did make me wonder how Dear America’s personal story sits alongside any number of equally human narratives — say of all those would-be immigrants too poor to even try, or all those who do feel somehow skipped over. So as a white guy with secure citizenship, those are some forms of armchair empathic humanizing your book opens up for me. Which empathic channels did writing this book (of course from a much more vulnerable place) open up for you?

Well I included that scene with the attorney for the reasons you just described. And again, I didn’t want to belabor it, right? I thought simply presenting that scene would signify that I consider it worthy of reflective engagement. I thought that scene had something to show people on the left. And by the way, I don’t consider myself a person on the left. I just don’t. I mean, of course when somebody labels me undocumented, gay, Filipino, they probably also can label me as on the left. But I don’t really know if that says something accurate about my political orientation, or just imposes somebody else’s definition. I’m responding to systems I didn’t create, right? So I try to avoid these simplistic binary assumptions that all people, all Asian immigrants, all Latino immigrants must be on the progressive side on every cause — because they’re not.

Sure, or that they would all vote Democrat if they got citizenship rights.

Exactly. In reality, a lot of Latinos (some people would say 20 or 30 percent) don’t support DACA. But where do you see that perspective in public conversations? Where do you see Asian Americans (this country’s fastest-growing immigrant population) in these conversations? So right after that exchange with the attorney at MIT of all places, I called my dear friend Reshma Saujani, who founded the organization Girls Who Code. Reshma is Indian American, and I said: “Okay, I just had this really intense conversation with this woman at MIT. At MIT!” I kept saying that to her. But I basically meant: how do we really start this public conversation about immigration among Asian Americans? Reshma and I are trying to figure that out for ourselves right now.

Whenever people from the left talk about race and immigration, or whiteness and white privilege, I never know where precisely Asians and Latinos fit into these conversations. I often find those conversations around white privilege lacking in nuance. I try to separate specific white people, and whiteness as ideology, and white privilege. I think of those all as related of course, but also as different from each other. But you see this propensity on the left to kind of glob all these topics together and just say: “We’re against white supremacy.” Well, what about all the white people also against white supremacy? What about all the Latinos and Asians who don’t know exactly what people on the left mean by “white supremacy,” but who have grown up thinking lighter skin is better, or thinking that to become American means in part getting closer to white America, which means distancing yourself from black America?

Well we haven’t yet talked much about how colonial histories play crucial if often unspoken roles in tying together so-called “legal” and “illegal” constituencies. When you call for a “human right to move” (a right that governments should “serve,” not “limit”), this of course might raise for certain audiences questions such as: “A right given by whom? Protected by whom? Under what authority or obligation?” When you describe your “toxic, abusive, codependent relationship with America,” certain readers might say they never knew about or signed up for or actively took part in this relationship. So how do colonial histories factor in here, and bind together everybody taking part in these conversations, whether or not they want to recognize that fact?

I find it ironic to answer that question, because actually I haven’t left this country since I first arrived at age 12. America is all I know. I’ve probably seen more of America than most Americans. But I do believe we think about immigration in this overly America-centric way. We just ignore the global implications of how we got to this point, right? And again, I worked hard not to overwrite that part of the book, because I do think that storytellers, journalists, filmmakers, artists need to lead the way in creating space and putting into language all these various different perspectives we all occupy.

And then for this idea of the human right to move, and what that might look like, I’d argue that this human right already has created the basic economic structure of our present world. So when somebody asks “Freedom given by whom?” I might ask right back: “Well who gave Magellan the freedom to go to the Philippines and claim it for the king of Spain? When did God sign the document giving certain people the right to their manifest destiny?” Or I first encountered “The White Man’s Burden” in an epigraph from James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time. I just assumed this had something to do with conversations about black and white America. As I mention in my book, I only learned much later that Rudyard Kipling wrote this poem specifically to convince the American government and the American elite of this need to take over the Philippines, with Kipling giving the subtitle “The United States and the Philippine Islands.”

Similarly, I only learned after a long time why my own name “Jose” has no accent on the “e.” My Spanish teacher (I actually was pretty bad at Spanish) Señora Kilmer would always include that accent, and I’d be like: “Filipinos don’t put accents on their ‘e.’” So finally, after we’d agreed on this book’s cover with my handwriting and all that, the HarperCollins copywriter wanted confirmation that my name had no accent. I said: “Well I’m pretty sure, but let me go confirm it.” I texted my friend Anthony Ocampo, who wrote the book The Latinos of Asia: How Filipino Americans Break the Rules of Race. He put me in touch with his friend Jonathan Rosa, who works on linguistics and anthropology at Stanford. A couple days later, Jonathan told me: “Your name ‘Jose’ comes from when Spain took over the Philippines. And when the Spanish left and the Americans took over after the Spanish American War, they brought typewriters to the Philippines, and their typewriters didn’t have accent marks.”

So even my name itself traces those complicated histories, that Spanish colonialism and American imperialism, though it took me 37 years to find this out. That just stunned me, and seemed this symbol of how history remains so present in our lives. I mean, I wish I could have gone longer and longer and longer talking about history. That just disrupted this book’s narrative too much, so we had to cut a lot.