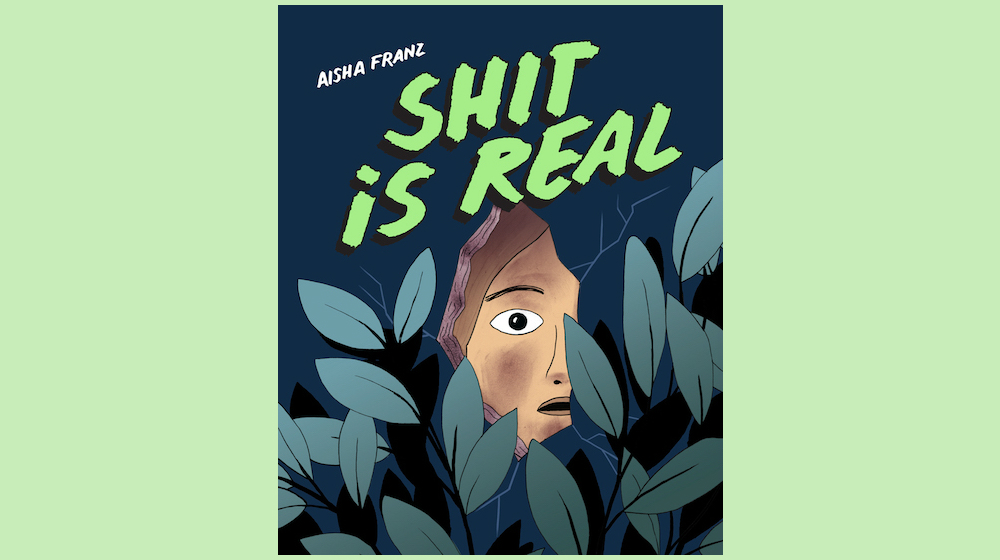

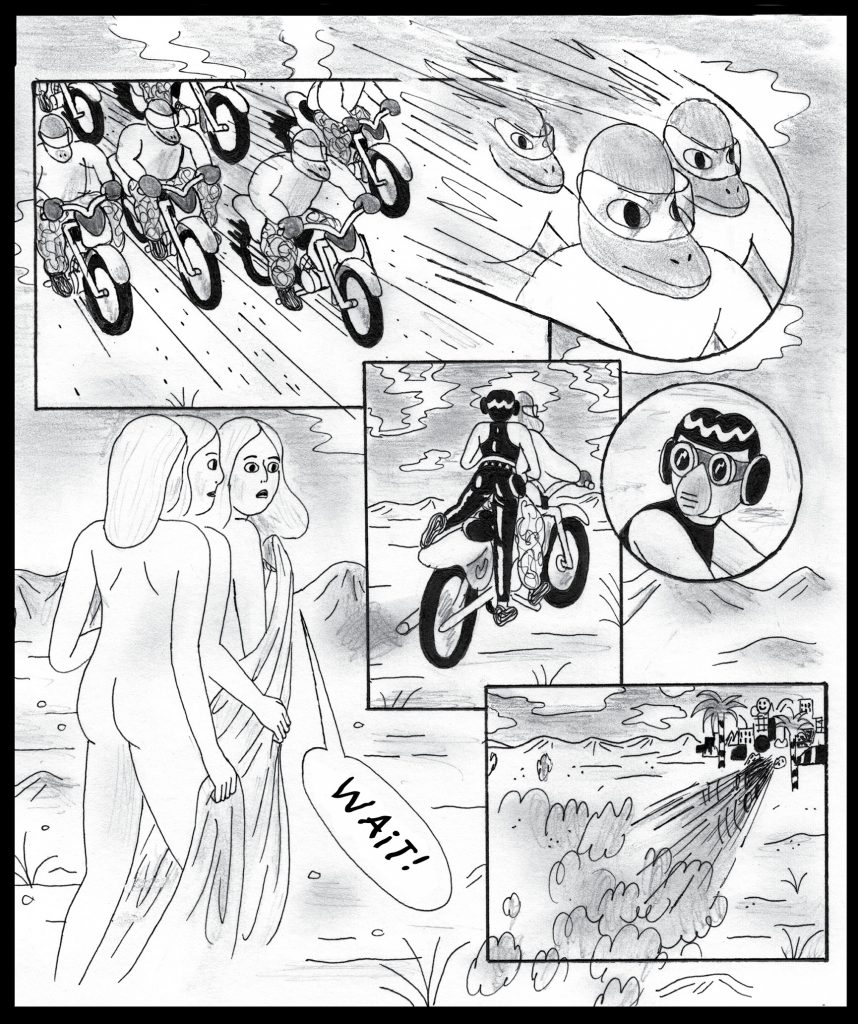

Aisha Franz is an illustrator and comic book artist who lives in Berlin. Her new graphic novel Shit is Real takes place in a slightly futuristic world and features a young woman reeling in the aftermath of a sudden breakup and move. The protagonist’s anxiety plays out in a narrative world of ultramodern technology and lizard aliens, and throughout the story, Franz’s artwork uncannily conjures both a sense of familiarity and displacement. Reality blends with dreams, as well as the hyper charged digital environment.

Shit is Real is the second graphic novel Franz has published with Drawn & Quarterly (her first, Earthling, was released in 2014). I wrote to her to ask her about her method of blending domestic realism with “off” reality, as well as her life as an artist in Berlin.

NATHAN SCOTT MCNAMARA: How did you put together the tableau for the slightly futuristic world in Shit is Real?

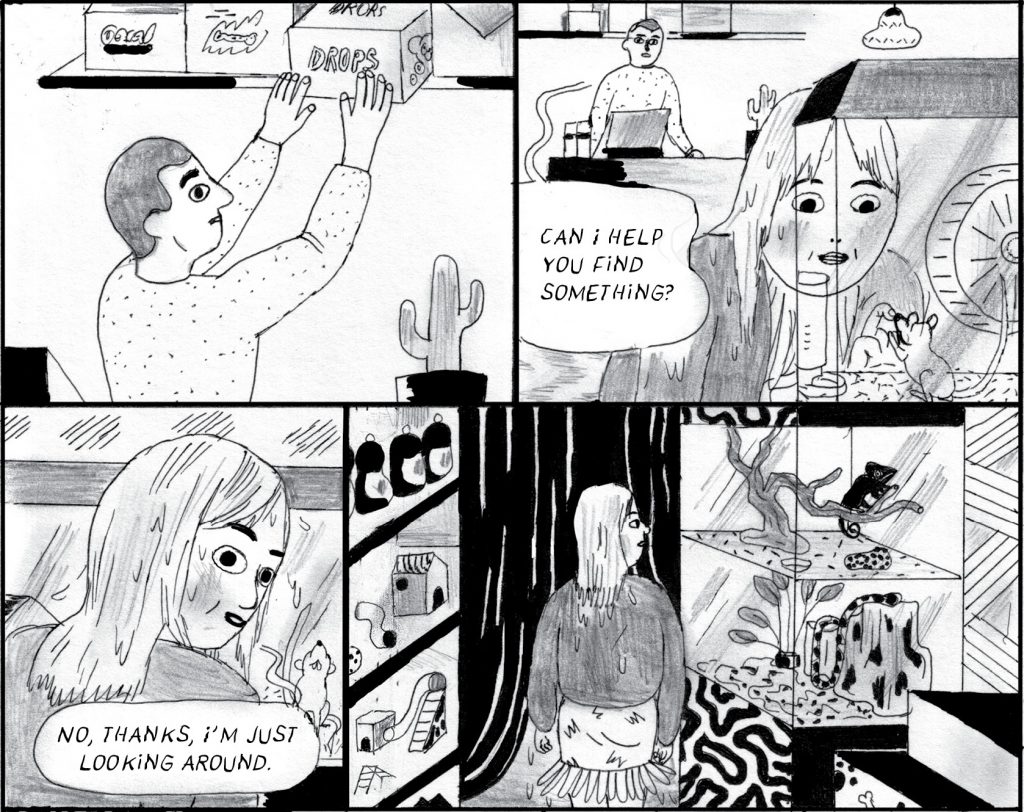

AISHA FRANZ: When I decided to start working on a new comic I was intrigued to do a science fiction story. At first I wanted to do a real genre fem-sci-fi and see how this would turn out, but it quickly morphed into something else where the sci-fi elements ended up playing a secondary or background role. In my work I usually try to avoid depicting real people and real places; I like to create more general places to be able to focus on the story and relationships between characters, and maybe that makes it more relatable for a wider audience. The near-future surroundings in Shit is Real let me do this.

Then the decisions about certain details come very naturally. It’s not trying to be realistic — it only has to work within its own vague universe while not wanting to diverge too far from what we are used to now.

How did you first get interested in dystopias or parallel universes? What were some of your first experiences with the genres that you’re touching on or subverting in this graphic novel?

I don’t know if there ever was a moment that got me interested in particular. It’s more that to me the line between reality and a reality beyond, like dreams, is very flexible and sometimes not existent in our everyday life. Parallel universes are omnipresent in our subconscious and make themselves “apparent” — sometimes more and sometimes less. Two good examples are the films of David Lynch or Haruki Murakami’s books — their work has definitely served as an influence on this kind of sensibility for our slightly “off” reality.

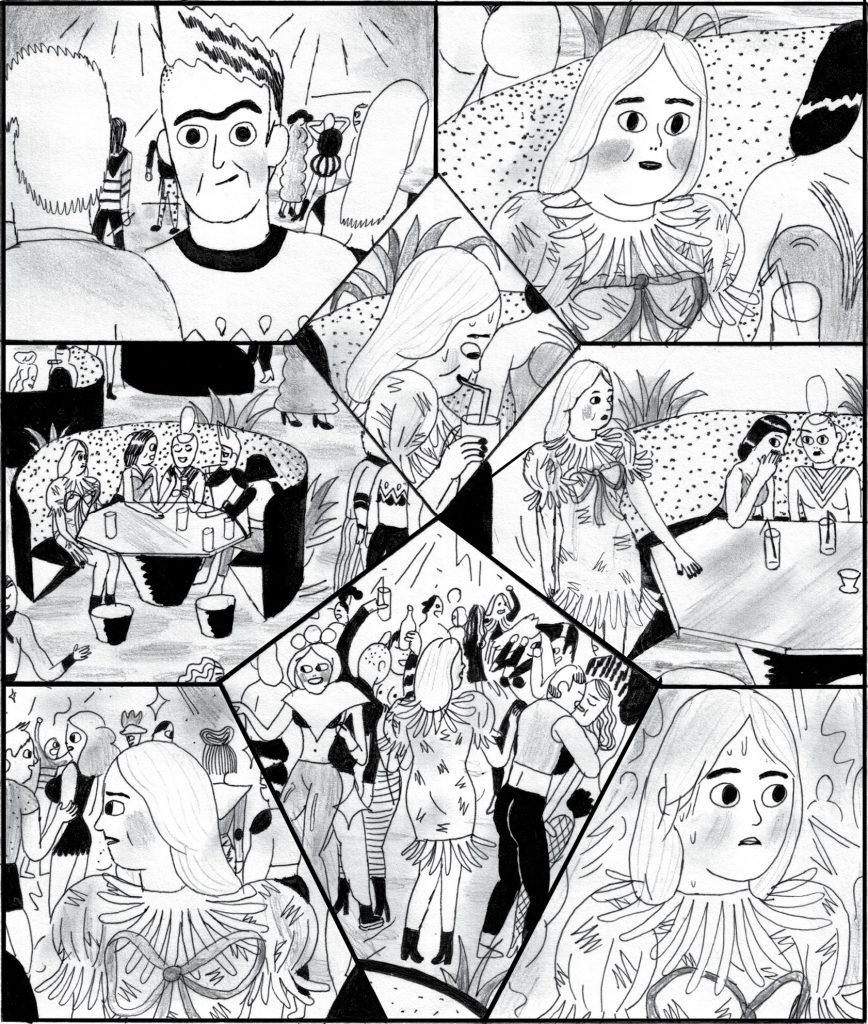

The book seems to weave between domestic realism, futuristic dystopia, waking life, and nightmares. You also vary illustration styles. Why are mixed modes integral to this story?

Process related. If you work on something over years and in chunks, style and ideas naturally change. I like to keep that process part of the book; it’s more honest also in terms of how personal the story is. I don’t write a script beforehand and then draw the story. Oftentimes I still don’t know where the story is going when I’m halfway through (not knowing that I’m halfway through). Also, mixing it up a little keeps you excited and curious — I don’t like being in the situation having to just work, work, work to finish something without giving imagination any space.

What did you think Shit is Real was going to be when you first started writing and drawing it? How is it different than what you first envisioned?

It was meant to be a lot more sci-fi-y, but also, at the beginning, I thought of making something more critical of technology (digital age). Then, over time, while working on the book I changed my opinions and became more interested in technology and theory connected to that idea, so I diverged from the initial point I wanted to make. It’s not about technology anymore — it’s about being human.

What were your favorite scenes to draw?

The desert lizard alien scenes. Another reason for working with these parallel universes and dream zones is for the simple reason that it allows me to do almost whatever I want. Like certain rules of logic are suddenly obsolete and you can use that space to really drift off.

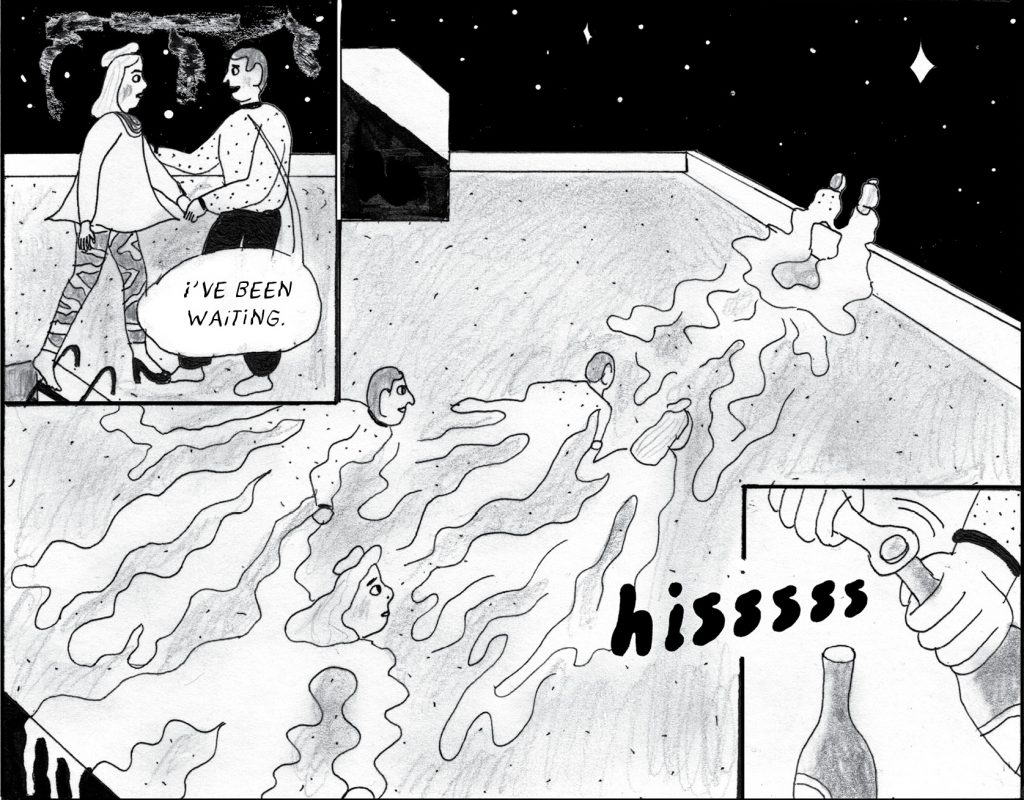

Shit is Real is full of nightmares that convey the anxious energy of our protagonist’s plight while also surreally nudging the story forward. Do you enjoy dreaming? What do you find useful (or frightening) about your own dreams?

Lately I haven’t been dreaming so much unfortunately, and I miss it. Although, the type of dreams I enjoy the most are the most realistic ones. They are only slightly off and very odd, and sometimes I wish real life would be a bit more like that. In the book those dreams serve more like a darker or more ruthless metaphor of what the protagonist is going through.

When did you first start making and distributing comics? What were the models for doing it?

As a student in art school I was first exposed to underground, independent comics and anthologies like Kramers Ergot and the Finnish collective Kutikuti. That’s what got me into making comics and therefore making zines. With a few other students we would go to different comic festivals in Europe. Later on, together with other artists based in Berlin, I was part of a mini comic distribution collective called Treasure Fleet to show our work at fairs and comic festivals. It’s financially easier, and you are also much more visible within a group rather than on your own.

What’s your favorite part of the comics scene in Berlin?

Berlin is always understood as a place with a buzzing art and comics scene, which is partly true. There are so many people living here who are somehow related to the illustration and comics scene. The reality is, though, that there aren’t so many occasions and events at which people can actually hang out and create stuff together. I guess it’s partly because Berlin also is a city of fluctuations; many people move here but only stay for a little bit and then leave. Berlin can be great; it is still comparatively cheap and has a lot to offer, but it oftentimes (especially in the winter) feels more like a rabbit hole —people hiding away, and it’s hard to stay in touch and stay active.

With my dear friend Johanna Maierski, the wonder woman behind Colorama, we are trying to close the gap between those loose ends of the local illustration and comics scene by organizing a collaboration project called CLUBHOUSE. The idea is to bring people together to collaborate on a riso printed zine, but the outcome is almost like a side effect. What’s more important is to create a platform for people to work together, exchange ideas, and simply get to know each other and make stupid jokes. I think it has had some sort of effect. Colorama, the studio and the publishing house, has managed to become some sort of central hub, something which had been missing before.