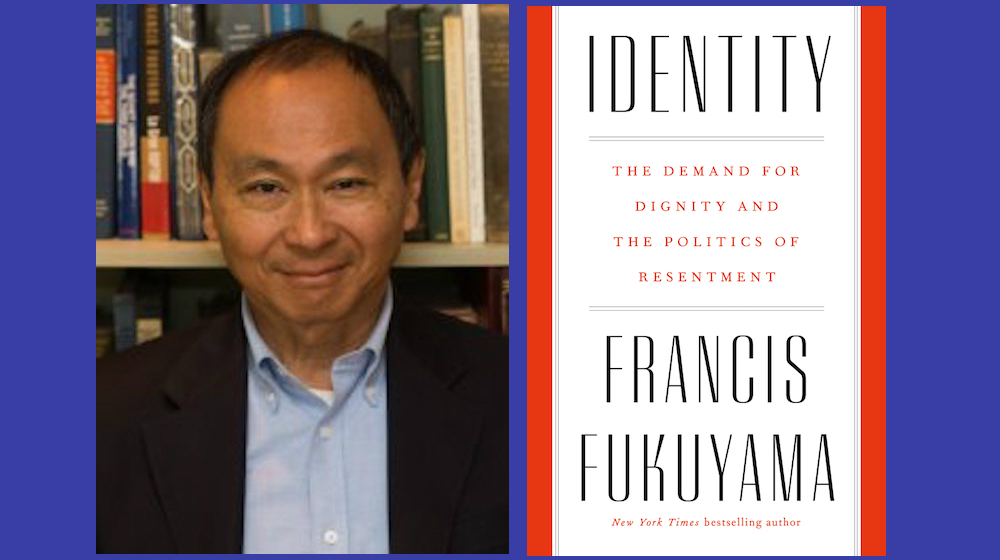

How might Platonic conceptions of thymos (so-called spiritedness) play out in present-day populisms? How might drives towards recognition of equal and / or superior status draw certain identity-based groups together and / or pull larger national constituencies apart? When I want to ask such questions, I pose them to Francis Fukuyama. This present conversation (transcribed by Christopher Raguz) focuses on Fukuyama’s book Identity: The Demand for Dignity and the Politics of Resentment. Fukuyama is Olivier Nomellini Senior Fellow at the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies (FSI), and Mosbacher Director of FSI’s Center on Democracy, Development, and the Rule of Law (CDDRL). He has written widely on questions concerning democratization and international political economy. His The End of History and the Last Man, published in 1992, has appeared in over 20 international editions. His other recent books include Political Order and Political Decay: From the Industrial Revolution to the Globalization of Democracy. Fukuyama chairs the editorial board of The American Interest, which he helped to found in 2005.

¤

ANDY FITCH: One basic motivation for writing this book (and also operating across your career) involves, in fact, developing a revised theory of human motivation. So could you first sketch a broader intellectual context, and then a more acute present-day U.S. context, in which you sense the greatest need for an expanded theory of human motivation pushing beyond classical economic models (models adopted both by free-market capitalists and by Marxists) positing the individual who rationally maximizes his / her material well-being as the driving force shaping modern societies?

FRANCIS FUKUYAMA: I’ve always considered an economic model based on rational utility-maximalization (which unfortunately dominates the social sciences in the United States) too reductionist, and insufficient to describe crucial aspects of human behavior. My current book, for example, emphasizes thymos, an ancient Greek concept usually translated as “spiritedness,” but which also has a lot to do with feelings of identity — the idea that we possess an inner self which needs to receive recognition and respect from other people. Thymos here connects to passion more than reason. When we don’t receive this kind of respect, we don’t feel treated as a human being. When we see others denied this type of recognition, we sense a denial of their dignity. And given these types of intolerable conditions, anybody might act against basic economic models of utility-maximalization.

Just to give one contemporary example, a lot of Brexit voters heard in advance that the decision to leave would be disastrous for the British economy, that their own incomes would drop, and so on. They responded: yes, I will accept that loss — so long as it gives us better control over our borders and we have fewer foreigners entering the country. Here you see thymos triumphing over any narrow economic understanding of how people think and make decisions.

Similarly, if you go back to The End of History, published in 1992, in the last few chapters I discuss thymos. I speculate on developments that could upset the democratic world order. I say that, in the stable and prosperous democratic state, people still want recognition, sometimes specifically recognition of being superior to other people. And even in a democratic society you never achieve real equality and equal respect, so people who feel left out inevitably will demand dignity, and those demands will continue to roil possibilities for stable democracy. Identities attached to religion and nationalism likewise will never feel fully satisfied. In Catalonia today, for example, people might live in a prosperous Spanish democracy but still not feel that they have a complete identity, or that it gets properly recognized. Those forces craving recognition operate everywhere, and they don’t follow any straightforward economic models of rational self-interest.

So I’ve worked with thymos for a long time now, but recently I’ve seen a big shift in that direction in political movements across the world. In our recent U.S. midterms, Paul Ryan advised the president to tout the prosperous economy, the increases in wages and so forth. Trump listened but basically ignored that advice. He spent all of his time speaking about this supposed invasion from Central America, and how he wanted to end birthright citizenship, and send the army to the border. That’s basically identity politics talking — in the U.S. as much as anyplace else.

Identity also describes modern behavioral economics persuasively challenging certain classic conceptions of humans as rational economic actors — but without delivering its own broadly scoped account of how / where human values or motivations do originate and do manifest through individual actions and collective social conditions. Could you situate approaches pioneered by behavioral economics within your own account of human motivation, and describe where you might depart from behavioral economics in attempting to articulate more affirmatively what individuals and collectives do strive for or should strive for?

Behavioral economics has effectively challenged the rationality part of the rational-utility-maximalization paradigm in standard neoclassical economics. Its studies have shown that people do not decide rationally. Or from Daniel Khanemen we get this idea of two types of cognitive activity, often with default behaviors taking over and preventing people from making more rational decisions. This shows us that human beings don’t constantly or even consistently maximize or protect their own interests.

But my problem with behavioral economics comes from it not developing any alternative theory of human nature that would answer the question: okay, so humans then act in the interest of…what? And of course behavioral economics often just sticks to emphasizing refutations of self-interested behavior (often just showing, for example, that we don’t take the time to do the type of reasoning that demands thinking through various possibilities and making complex calculations). So I agree with this account that behavioral economics has given us, but think it misses the idea of thymos propelling you towards certain kinds of decisions based on your own understanding of yourself and your relation to other people, and your need for external affirmation of your worth and your dignity. Now a lot of economists, when confronted with this kind of challenge, will just say: “Well, that desire for respect is just another preference. Just as some people want money, some people want dignity.” But I consider that response inadequate, because I don’t think of thymos or dignity as a mere preference. I don’t think you can directly compare them to material satisfactions producing a sense of well-being. They instead have to do with intersubjective relationships. And furthermore, a lot of what drives this desire for recognition again comes from a desire to be recognized as superior — so your relative position is at issue, not just some absolute level of satisfaction.

This all makes thymos-driven relations much more difficult to comprehend and to calculate. In neoclassical economics you often can reach a win-win situation, where you negotiate with somebody and both of you end up better off — whereas when you want superior recognition, you can’t get this without making somebody else feel bad, right? Your own status depends on somebody else having lower status. That type of struggle for recognition plays out quite differently from our standard economic models for how people interact.

Most generally perhaps, Identity questions any theory of human motivations that prioritizes the optimization of some limited set of goals, and calls for a more vectored approach to determining (either for descriptive or prescriptive purposes) an appropriate balance among a confluence of motivating impulses. And here Identity reinforces liberal-democratic visions themselves eschewing any single-minded optimization of, for instance, a rugged individualism or a hyper-regulated collectivism. “Balance” no doubt is an overused, underdefined term in American cultural life at present. But could you discuss the emphasis that Identity (and that your overall corpus) places, both for broader social analysis and for concrete policy recommendation, on this concept of “balance”?

Sure, and as you suggested, a lot of my other writing (for example my “Political Order” books) has argued that any effective political system has to find a constructive balance between the ability to act collectively (in a rapid, decisive manner for the common good), and at the same time the ability to remain representative, participatory, consultative, democratic, and so on. One of these basic functions often comes at the expense of the other. But a strong democracy requires a certain balance where you can act decisively when you need to, yet where you also have the legitimacy that comes from public consultation. Getting that balance right is almost impossible to specify in some clean and universal way. And here Plato’s three-part model of rationality, desire, and thymos adds to the complexity.

Or often we might need to consider taking on a job or a task we otherwise find demeaning — simply because we need the money. We face these trade-offs constantly. Should I relinquish my dignity in this situation? Should I cut corners as a means of prioritizing my own self-interest? Just as in designing a political system, it’s very hard here to establish any clear set of rules for how everybody should make these tradeoffs. But we do face these kinds of calculations all the time, and they do depend on our personal situation and the very particular choices we make. So we need balance both at a broader macro level and at a micro individual level.

And “balance” of course doesn’t necessarily mean some 50-50 split as defined by extremes of the day, but instead here often seems to suggest something more qualitative than quantitative — more like “ballast.” So for an example of a more concrete political calculation, how might American traditions of robust immigration find themselves renewed and recalibrated by your call to depart from polarizing rhetoric about open borders or about building a wall — instead first building consensus around qualitative questions of how we might define well-assimilated immigration, and only then sorting through quantitative questions of how many such well-assimilated American immigrants we have the capacity to settle at any given moment?

That approach you describe makes sense to me. Our immigration debate has become dysfunctionally polarized between these two extremes of “Keep them out entirely” and “Open up this country as much as you can” — whereas I believe we ought to focus much more on the long-term integration of newcomers into a democratic, egalitarian, rule-of-law-based, constitutionally secured American political culture. We really haven’t done that. So I do appreciate the idea of first getting people to agree on the ultimate goal. If we could focus on this question of long-term assimilation, then a lot of people currently dead-set against immigration might not feel so resistant. I mean, that’s my guess and certainly my hope. I strongly support immigration, and believe it has greatly benefited this country. But I also believe that immigration has succeeded for us because eventually these immigrants do get assimilated. They’ve brought both vital diversity and a broader acceptance of the general consensus about how American society and politics should work.

Again, your own method here seems quite Socratic, and not “Socratic” as people use that word in law school, but in terms of dialectical procedure: starting from a definitional model that can create a foundational consensus from which then to build a broader policy recommendation. And here returning to Socratic / Platonic accounts of vectored human motivations, and of multiple thymic drives, could you parse further your own conceptions of isothymia (demand for recognition / respect as an equal) and of megalothymia (demand for recognition / respect as superior), perhaps first by tracing your longstanding interests in how a modern market-based society can constructively channel megalothymic ambitions, and then Identity’s more pressing concerns with how populism conjoins an individual leader’s megalothymic ambitions to a much broader constituency’s isothymic complaints about having its general way of life disrespected? Basically, how much can / should we pull apart isothymia and megalothymia to see them as clearly as possible? Does the existence of one invariably imply the other? Does nobody feel their isothymic claims threatened unless someone else asserts megalothymic claims, and vice versa? Does the populist leader play the role of a displaced intermediary in certain scenarios: in which, say, I feel threatened by some external group’s megalothymic claims over my group, and I respond by affirming one in-group individual’s megalothymic claims over me?

They definitely are both rival forces and interconnected forces. Again isothymia describes this broader phenomenon where people desire recognition as an equal, or as given the same basic respect as other people in society. All of the big 20th-century social movements in the United States on behalf of African Americans, women, the LGBT community and so forth, come from this isothymic drive. Isothymia also drives older historical phenomena like nationalism — where a certain linguistic or cultural group feels inadequately recognized because it lacks its own country, and so makes the basic demand for equal national representation. In our era, this might mean that a cultural group wants its own seat at the United Nations, and wants equal respect among those nations.

Megalothymia is not as widespread. Not everybody considers themselves God’s gift to mankind. Not everybody feels an absolute need for others to acknowledge one’s superiority. In any given society, these particular types of ambitions don’t get evenly distributed. And I believe that our founding fathers recognized the fundamental threats to democracy posed by these very ambitious individuals. Of course they devised a basic system of constitutional checks and balances spreading power among many different types of offices: with two distinct branches of Congress, a separately elected president, a separate court system — as well as all of the divisions among federal, state, and local government. Each of these divisions protects against excessive concentration of power within a single individual. Here I think these founders drew an important lesson from the Roman Republic’s downfall when Julius Caesar became the single dictator.

And then in terms of how a market economy might help to diffuse some of that megalothymia by giving especially ambitions individuals the chance to instead become incredibly rich — The End of History actually gives the example of Donald Trump as somebody who can satisfy himself by becoming this celebrity real-estate developer, though it turns out that wasn’t enough for him.

Even when you throw in a TV career.

Right. But again even there, these two demands of isothymia and megalothymia overlap in complex ways. The demand for equal dignity can rapidly turn into a demand for superior recognition. You see this especially clearly once nationalism comes about. 19th-century German nationalism for example began with a call for equality, a call for Germans to live in their own single unified state. But this call quickly transformed into a desire for the German people to dominate neighboring nationalities. You can see something similar happening today in Putin’s Russia, which felt deeply humiliated by the Soviet Union’s collapse and the very weak economic situation throughout the late 1990s. Then Russia reclaimed a certain status under Putin, and wanted to regain dominance over the Baltics and other neighboring territories and societies.

Another big problem with isothymia comes from the fact that we all might, in theory, be equal moral agents, but we are certainly not equal in terms of the various types of respect you can get. And if you show yourself to be a tremendous baseball player or musician or poet, you deserve superior recognition and respect to somebody who doesn’t — whereas if we assume that everybody possesses precisely the same amount of talent, and deserves the same types of respect from society, then we’ll never recognize excellence or even just distinctive skill in certain fields. Similarly, if we don’t disrespect anybody, then we can’t even censor or exclude murderers, rapists, or just arrogant assholes whose behavior doesn’t deserve the same basic moral respect by which a society functions normally and normatively. So isothymia and megalothymia probably do need to get defined in some relation to each other, though I also think we can and should consider them as psychologically separate. I think they derive from separate parts of the brain, and push us in quite different directions.

Thymos, in Plato’s Republic, emerges specifically among a guardian class accruing honor due to its departure from any self-aggrandizing, individualist, materialist focus. But here I also want to make clear that we can’t just think of isothymia as good, and of megalothymia as bad, that we can’t just ask “How might democratic society optimize isothymia?” but again need to reconceive what a balanced, coherently integrated isothymic / megalothymic whole might look like at the level both of the individual and of the collective. Plato’s guardian class, for example, does consider its ostensibly modest habits superior to ordinary citizens’ more indulgent tendencies.

Some sort of megalothymia presumably drives all great leaders, right? Even for George Washington, for Lincoln, for Churchill: without this drive for recognition as a dominant leader, without this drive to establish their own ideals and values, they never would have done the seemingly selfless things they did. So megalothymia does drive human action, whether good or bad action. Bad leaders like Stalin or Hitler also possess a strong megalothymic drive. You can’t attribute a fixed moral valence to it.

And we can say the same with isothymia. That drive might serve as the basis for our modern democracy. But any enforced sense of universal equality would bring its own unjust outcomes. Again for one more trivial example, think of how, today, high schools recognizing a valedictorian and so forth makes everybody else feel bad, so that these schools keep adding new awards for different things. As a junior-high student, I myself received the award for best improvement in music. I went from a D to a C-plus. That attempt at distributing recognition with perfect isothymic equality presents its own distortions and unjust evaluations, and again obscures the reality in which some people are superior in some specific sense.

Plato’s guardians also exemplify a fierce, passionate loyalty unfamiliar to a contemporary left-leaning intellectual class quite skeptical of such emphases upon spiritedness, cultural orthodoxy, collectivized patriotism. At the same time, progressive calls for isothymic social equality often carry their own streak of smug moral superiority, through their critique of supposedly retrograde conservatives. And while conservative claims to a “moral majority” not long ago had their own domineering streak, we now hear from the right a more aggrieved demand for equal respect and recognition, a demand that until recently this group itself might have characterized as a form of “whining,” as somehow weakening our cultural fortitude and diminishing prospects for the heroic individual to climb to megalothymic heights. So amid these teeming contradictions in present-day manifestations of thymos, could you outline Identity’s case for how group-recognition claims made by both left and right impede prospects for some newly stabilizing mode of universal recognition to emerge — with progressive parsings of intersectional sub-group categorization pushing us ever further away from re-conceiving a collective democratic citizenry, and with conservative appeals to monocultural racial, ethnic, religious identities pushing us ever further from a credo-based patriotism?

Let’s start with the left, because I think that this isothymic demand for equal recognition in modern identity politics does go off the rails at a certain point. This approach might start from a basic demand for justice, but often ends up demonizing people who do not fit within preferred identity categorizations based on race, ethnicity, gender — often rigid categorizations that liberal thought itself criticizes. So take the concept of white privilege, and the idea that one’s physical status as a white person makes you incapable of empathizing with somebody not white, or even unqualified to speak about certain sensitive social topics because of how race limits your perspective. I consider that idea a tremendous disservice to the fact that people can empathize, can think outside of themselves and of the ways in which they were raised. The identity somebody wants to place on us doesn’t need to trap us in these ways — again just as liberals themselves long have argued.

And if these excesses in isothymic politics don’t feel like the biggest problems across our broader society, certainly on a lot of university campuses (and in the arts and related cultural spheres) this type of thinking has become very powerful. Take the white artist Dana Schutz, who did a painting of the murdered Emmett Till, and was told to destroy the painting. As a white liberal, Schutz wanted to do her best to empathize with the pain of black people persecuted in the South. But she was told she had to destroy this painting, because a white artist couldn’t possibly understand that experience. So here we have an example of adopting a stereotyped and vastly over-generalized understanding of an individual, based on how racial identity supposedly limits her.

And then on the right, as you said, we see this adoption of a victimization mindset, especially by many people in the alt-right or white-nationalist movements. We get these absurd accounts of whites having their rights violated by minority groups. So we seem somewhat trapped right now, with both sides asserting biological identity in a way that’s not really compatible with liberal-democratic government.

Outside of that particular U.S. context, especially in Europe, we also see new challenges posed by an emphasis on multiculturalism. Here again I think we’ve misunderstood the nature of equal recognition. In theory a liberal democracy recognizes individual citizens as rights-holders on a universal basis. Though with the rise of multiculturalism as an ideology, people began to say: “Well actually, liberal pluralism means not a pluralism of individuals but a pluralism of cultures. We have to give all cultures an equal degree of respect. We need to think of Western culture as just one of many cultures, with none superior to any other.”

This approach leads to a lot of contradictions, because a lot of cultures themselves don’t respect human beings equally. You see girls living in Europe sent back to Pakistan and forced to marry someone they haven’t chosen. Society itself has to make a choice in these cases between respecting the rights of a community or culture, or of this individual girl. I believe we choose wrongly here when we prioritize the culture over the individual. I don’t think a liberal democracy can (or at least should) violate the principle of protecting this young woman’s individual rights just for the sake of tolerating a culture that itself never even pretends to endorse liberal tolerance. I also don’t consider all cultures as somehow born equal. Certain cultures actively discriminate against women, gays, and a lot of other groups in ways that I consider incompatible with a liberal culture that says we need to recognize and respect all these groups. So those are some of the neuralgic issues surrounding equal recognition right now.

You described megalothymia as relatively limited in its distribution across a given population. You also have pointed to a heightened prevalence of combative megalothymic claims at present. So hopefully by now we’ve started to make clear how Plato’s mythic, seemingly timeless conception of thymos always takes on much more localized historical manifestations. I appreciate, for instance, Identity’s account of how the strikingly uneven economic gains associated with digital technologies might coax forth, catalyze, and seem to legitimate certain highly successful individuals’ megalothymic ambitions. And here Identity even made me wonder: do contemporary screen technologies likewise encourage megalothymic self-conceptions in all of us? If one’s drive to megalothymic recognition used to find satisfaction so long as the small band of humans with whom one interacted confirmed one’s sense of superior self-worth, could I fairly characterize a megalothymic self-conception as the feeling that “I am at least as good as the rest of the world combined”? And have we never had such a narcissistic crystallization of “the rest of the world combined” as we do today whenever we face off with our digital screens and the broader world they represent for us?

I hadn’t thought about it from that specific angle. But from a certain perspective, the followers you have on Twitter or Instagram become this source of recognition, confirming that people want to pay attention to you, which probably does drive a lot of this behavior. Or just think of all the teenagers right now who will do unbelievably risky things to become YouTube stars — which you also probably could characterize as a drive for superior recognition. Yeah, that’s a good insight.

And just to broaden that social-media focus a bit, maybe we could pivot to Identity reworking classic sociological narratives about the proto-populist “Hans,” who departs from his provincial homeland’s stabilizing social roles and norms, who suddenly finds himself adrift amid a much more anonymous, heterodox, industrial-era city. Here Hans’s personal dislocation intensifies his susceptibility to aggrieved calls for group recognition, and ultimately to unifying / scapegoating claims along the lines of: “We, your true brothers and sisters, know who to blame for your bad feelings.” And here I did picture demoralized ethnic Germans in a depleted post-WWI Austria, or would-be jihadis growing up in bourgeois comfort on the outskirts of today’s London. But I also thought most specifically of American baby boomers retiring and suddenly sitting around at home a lot, with some filling the time no doubt by reading cranky social-media posts and watching way too much Fox News. Particularly among those boomers whose own identity seemed to have been shaped (by parameters of occupational / parental life) almost as cohesively / constrictively as Hans’s had been by his provincial community, who today find themselves gazing out at a new (historically unprecedented) frontier of long-term retirement, who feel themselves recently bereft of perhaps their most cultivated social purpose and capacities for agency, and who now seem to be turning inexplicably sullen, rigid, belligerent — has a certain class of such boomers become the new Hans?

There’s something to this. This might take me onto some pretty dangerous ground, but I do sense, for example, a strong gender dimension to those dynamics you just described — because obviously gender norms and the ways men and women interact have been changing dramatically over the past few years. Most generally, we have these basic economic changes, with women continuing not just to move into the workplace, but to outperform men, especially in many white-collar occupations. Women get better educations, and graduate from college more often than their male counterparts. And at the same time, many men with fathers who had manufacturing jobs now might wonder: Well, should I instead train to become a nurse? Should I try for one of those traditionally female jobs? And then when they go out on a date so many norms have changed as well, with it hard sometimes to know for sure what new rules might exist in terms of sexual harassment and sexual assault, or various other interactions between men and women. So we have all of these normative parameters dissolving all around us, and many males feeling newly insecure, and the most pathological versions of these personal struggles giving us guys who end up as mass shooters or some equivalent.

Or again, in a lot of the right-wing pro-Trump groups, you do see this desire to assert a more traditional kind of masculine identity, to push back against all of these changes they resent. So in that respect also I think of how Hans might get seduced by Adolf Hitler — when Hans suddenly faces this very different social landscape from the one in which he grew up, and feels the strong need for some moral anchoring. Right-wing groups often provide that.

I also think of Hans as attracted to (not just repulsed by) new social conditions in which he finds himself, and again how that internalized confusion can get channeled in complex ways.

Sure just to pick one quite different example, you could go back to the September 11th hijackers. It turns out Muhammad Atta, for instance, had been going to strip clubs and watching pornography and this sort of thing in the months leading up to the attack. So again you see these guys suddenly faced with Western culture, which on one level attracts them, but on another level makes them kind of hate themselves as a result, and that leads them to lashing out violently against this culture.

Here questions of status (both within a group or a culture, and without — as one group compares its stature to another’s) likewise come to mind. You offer an incisive account of how liberal democracy finds itself devalued right now by a large class of workers (most acutely, in the U.S. context, lower-skilled white male workers) not only facing present and future economic threats tied to offshore labor and job-displacing automation, but simultaneously facing assaults to its basic claims to individual and collective dignity. And of course many such claims to dignity haven’t yet been fully disentangled from inherited conceptions of racial and gender hierarchy that we all should leave behind. So how do you suggest going about the tricky business of cultivating newly universalized (presumably more equalized) conceptions of dignity amid a distressed social group that by definition does need to lose some relative status, some relative power, for equality to prevail — and all amid this exacerbating real-life context of sustained structural economic precarity that hasn’t been sufficiently addressed for the past 40 years?

First of all, I think you need to listen carefully to what these voters say has driven them to a populist like Trump, and of course you do need to sort out a bit the more legitimate complaints from the illegitimate. Of course you don’t need to accept as legitimate the basic complaint that: “This used to be a white country, and it’s not any longer, and I dislike that fact, and I want to stop it.” You can’t accommodate that kind of feeling. But when you hear the complaint that: “I’m really worried about whether we’re assimilating immigrants properly — I think they could become good citizens, but we need to make sure that they do get Americanized,” I think a politician should be able to address the more legitimate components of that concern. And here I do think that you can walk and chew gum at the same time. You can address certain historical wrongs and contemporary disparities faced by certain identity groups, and you still can push for a stronger unifying identity. Good leadership does both simultaneously, but we unfortunately have not had a lot of that combined effort in recent years. We’ve instead had leaders who exacerbate those kinds of splits.

In terms of managing socially fraught status transitions, has post-Deng Xiaoping China done best in our recent past: for instance by allowing once-dominant groups in North America and Europe to keep their megalothymic self-conception intact on a subjective level, while gradually eroding the objective veracity of such claims — saving face, along the way, for everyone involved?

If this is their strategy, I don’t think it’s going to work very well. At a certain point the reality of growing power and wealth will make itself felt, and the reaction may be even worse for not having been anticipated. In a way, that’s what we’re going through right now — being disillusioned that China is not turning out to be more like us, and playing catch-up after they have sucked all of our supply chains into Asia. The one area where they have not done very well, however, is culture: very few people admire Chinese culture (apart from the fact that they’re wealthy), and China has failed to conquer much of the world through the export of literature, art, or even pop culture like manga or K-pop. Maybe this is still coming, but it would have to be a very notable development.

Here it also seems helpful to sketch how various motivating factors of economic grievance, demands for dignity, and demands for democracy might come together, or might get falsely conflated, or might pull apart. And here again I don’t want to dwell too narcissistically on the U.S., and would love to hear how you see rural-to-urban displacements, and / or uneven development of economic modernization and political modernization, playing out in China, India, Vietnam, the Philippines, Brazil, Russia, Hungary, Poland (the list could go on and on, and I’d still be interested). But more specifically, how might resurgent nationalisms now and still to come in such countries resemble and differ from our own nationalist upswing, and how might resurgent nationalisms resemble and differ from each other within these respective rapidly modernizing societies? What, for instance, might claims for identity look like now, and look like going forward, in a China that provides unprecedented economic gains while also intensifying economic disparities, reinforcing a narrow ethno-nationalist self-conception, and restricting claims to individual liberty and collective self-governance?

Well as you suggested, I find it hard to generalize about some of these different systems. I think in China the main issue involves the regime fueling nationalism to strengthen its own claims to legitimacy. Xi Jinping talks about several centuries of oppression at the hands of Western colonialism, and how the Communist party has re-asserted China’s dignity. I consider that a Chinese version of “Make China Great Again.” But in China this also means fortifying the bureaucratic elites already in power. You don’t have some grassroots movement pushing politicians in this direction. And similarly, in this very effective authoritarian state you don’t see much political pluralism to challenge the current regime.

Amid such ominous nationalist developments, I also do want to address your basic point that strong national identities sometimes have produced, yet need not inevitably produce, xenophobic, illiberal, internally and externally aggressive nation states. You describe for instance how a strong national identity in Japan, South Korea, China, has helped to cultivate an elite class focused (often enough, at least) on harnessing rapid industrial modernization towards collective economic advancement, rather than solely towards personal gain. You show how historically homogenous Scandinavian countries exemplify possibilities for national identity to bring along with it highly productive social capital in the form of a shared sense of trust, a collective commitment to self-regulating social norms, a collective concern for the well-being of one’s fellow citizens as supported by strong social-safety nets. So for some of the broader questions raised across your career: how might you ideally go about forging a new American nationalism that likewise could diffuse and / or contest dysfunctional zero-sum clashes among competing interest groups?

Identity provides a few examples of how this might be done. Part of it is educational, using public education to restore an emphasis on civics and citizenship. I think that national service would be very beneficial from a number of standpoints. It would emphasize to people that they have duties and not just rights, and should therefore take citizenship seriously. If done correctly, this type of national-service project could also bring together Americans from different races, ethnicities, regions, and classes in some kind of common effort.

At the moment, the military is the only large institution that does anything close to this, though it is pretty much walled off from the elites. And of course there are rituals and observances that give people an emotional sense of belonging. The Thanksgiving holiday was introduced and the sport of baseball was popularized after the Civil War, for instance, in order to create a greater sense of common nationhood — and both were pretty successful in that regard. But there is a chicken-and-egg problem here: polarization prevents us from agreeing on a strategy to re-bind the nation, and prevents us from coming up with the common narrative to build that common participatory citizenship. I mean, I consider this one of our biggest strengths, that for example on November 6th people could vote if they wanted to push back. They had the opportunity to do that.

Finally, since Plato himself theorizes thymos from within the messy domain of dialogue, with it never fully clear which characters’ statements one might attribute to the author, with Socrates and his interlocutors often not agreeing on whether they engage in isothymic or megalothymic exchange, with the triangulated reader him/herself perhaps feeling a sense of palpable recognition typically not provided by theoretical formulations, and with it never fully clear what role narrative context, dramatic irony, mythic constructs might play amid a Platonic dialogue’s definitional pursuits, what have you picked up formally as much as conceptually from Plato about how theorists of human economic and political motivations ought to go about their business? Or as a political theorist frequently engaged not just by quant-heavy analyses, but by the more broadly humanistic investigations of Plato, Rousseau, Hegel, Nietzsche, Marx, what else might you have to say about present social science needing not just different theories of human motivations, but a richer, more expansive range of discourse from which to draw and to which one might contribute?

I think that there are problems with both the humanities and social sciences today. The former has in many places gone off a deep end, with theorizing completely unconnected to any body of empirical evidence, or to any empirical methodology. This trend was legitimated by the postmodernist wave that hit the U.S. in the 1970s, and got attached to an identity-politics agenda that has distorted the aims and objectives of the humanistic project. On the other hand, the social sciences, led by economics, have become hyper-positivist, seeking a degree of empirical verification that is simply out of reach for important human questions. The result is that the social sciences tend to focus only on the most micro of questions, and to forget the broader approaches that animated earlier social theorists. That’s why I think it’s important to read old books that raise big questions, which can then be judged on the basis of as much empirical evidence as we have available today. That body of evidence is much larger than when those books were written, and thus an opportunity for “an old question asked anew.”