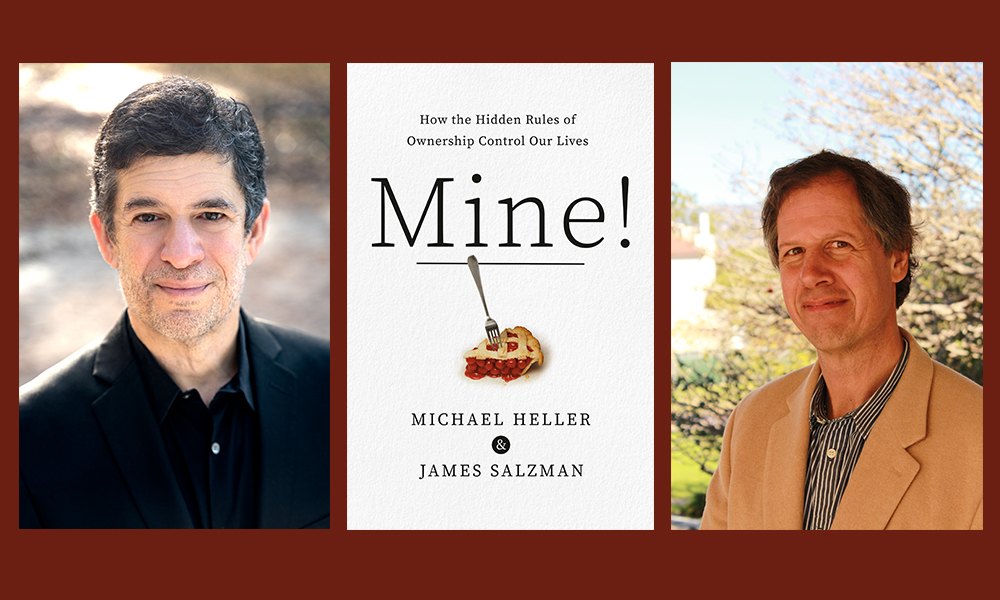

Why don’t you own that e-book you just bought? Why can’t you even hack your own phone? When I want to ask such questions, I pose them to Michael Heller and James Salzman. This present conversation focuses on their book Mine! How the Hidden Rules of Ownership Control Our Lives. Michael Heller is one of the world’s leading authorities on legal ownership. He is the Lawrence A. Wien Professor of Real Estate Law at Columbia Law School, where he has served as Vice Dean for Intellectual Life. His writings range over innovation and entrepreneurship, corporate governance, biomedical-research policy, real-estate development, African American and Native American land ownership, and post-socialist economic transition. James Salzman is one of the world’s leading environmental-law theorists. He is the Donald Bren Distinguished Professor of Environmental Law with joint appointments at UCLA Law School and UCSB Bren School of the Environment. Salzman’s broad-ranging scholarship addresses topics ranging from water to wildlife, from climate change to creating markets for ecosystems.

¤

ANDY FITCH: Could you first clarify the stakes for perhaps this book’s most basic point that, in our daily lives, we mislead or disadvantage ourselves if we fail to recognize claims to ownership as always strategically shaped, contestable, subject to revision?

MICHAEL HELLER: People often think of ownership rules as distant and legal and for someone else to decide. But that’s not true. Law is tremendously overrated. We face hundreds of ownership conflicts each day without even realizing. It might feel pretty natural to put some items in a grocery cart and consider them “yours,” before you’ve even paid. But what if someone reached into the cart and took out the milk? Then the eggs? You’d be shocked. But was any of it really yours?

It turns out that humans have just six simple stories everyone uses to claim everything in the world. The shopping cart relies on one of them: “Possession is nine-tenths of the law.” Each story feels so natural and self-evident that we don’t even question who has control (or why we don’t). With this book, Jim and I want readers to realize that ownership conflicts are all around us all the time, and always up for grabs — and if you’re not the one choosing, then someone else is choosing for you.

JAMES SALZMAN: Ownership provides the scaffolding that our society uses to decide who gets the stuff we all want. There’s never a single right answer for who should get what. It’s always a choice. But to understand these choices better, we first need to see how we navigate ownership rules every minute of every day. Which kid gets to pick the biggest piece for dessert? Who gets to drive in the HOV lane at rush hour? Who gets a COVID vaccine first? These are all ownership disputes.

MH: Right, my parents hated the sibling fights over who would get the biggest slice of pie. So they created a rule that, as the oldest, I’d cut the dessert into three pieces, but would pick last. I learned how to cut everything precisely into thirds. For my parents, this ownership engineering achieved their overriding aim: they no longer had to listen to the kids fighting. Ownership engineering occurs all over the economy and is incredibly powerful. Yet we often don’t even realize others are using it to achieve their goals.

Before we take up the six most basic claims to ownership (first-in-time, possession, labor, attachment, self-ownership, family), how might each claim presuppose a binary view of ownership as some ultimate “mine” or “not mine” — increasingly clunky categories as our economy reduces its emphasis on material goods and physical work? How might metaphors of a dimmer switch (rather than an on/off toggle), or a bundle of sticks (rather than some more solid foundation) help to illustrate today’s ownership-design approaches?

JS: Studies have shown that when we go on Amazon and click “Buy Now” for an e-book, or pay Apple in order to download a song, almost all of us believe we now own this item. But it turns out we don’t. We’ve essentially licensed a stream of ones and zeros. Amazon and Apple and other Internet behemoths have deftly adopted the “bundle of sticks” model of ownership. They give you some sticks, but they retain the power to take these back. In one notorious example, Amazon deleted the novel 1984 from consumers’ devices — something Big Brother would be proud of.

Also, you can’t share an e-book you buy. You can’t cut it up into a collage, or split it up into various files. Or consider your smartphone. You don’t own much of what happens inside. You definitely don’t own your phone’s operating system. You can’t hack your own phone. We still have physical, tangible objects like phones. And we still have ownership. But they don’t add up in the same way anymore.

MH: We get through our days by simplifying the sense of ownership, boiling it down to “mine” or “not mine,” like flipping an “on” or “off” switch. But today, ownership often works more like a dimmer. Online companies set the switch so you still think: I bought it, I own it. But Amazon and Apple actually have set the dimmer lower than that, giving you a little less, hoping you won’t notice the difference. This dimmer-switch metaphor speaks powerfully to all of our ownership stories, and helps clarify some otherwise quite puzzling battles.

So to start taking up those six basic ownership stories, first-in-time claims can seem intuitive and pretty close to fair — particularly when they can draw on historical convention, ease of administration, and a productive incentivizing of innovation. Could you give a couple examples, though, of the negative externalities that first-in-time claims tend to bring about? And more broadly, could you illustrate how first-in-time ownership design gets driven less by the seemingly straightforward question of who arrived there first, and more by forever contestable considerations of who gets to decide what counts as first?

JS: Think of the reality TV show Deadliest Catch. 20 years ago, you risked your life more by fishing for crab in the Bering Sea than by serving on foot patrol in Iraq. Why? Because Alaska used a first-come, first-served system. Whoever caught crab first won. Once the annual quota was reached, that season ended. This led to Mad Max-style races on the high seas, even in terrible weather. If you stayed in harbor, someone else would go out anyway, and catch what could have been yours.

Thankfully, Alaska reengineered ownership. Today, even on Deadliest Catch, nobody actually dies anymore. The editors have to work harder now to create narratives of dangerous voyages. Alaska has rebuilt its rules around an ownership approach pioneered in Iceland, basically allotting a share of the season’s quota upfront to individual boats (a version of the attachment story we’ll discuss later). This means that fishing crews can wait for more hospitable weather conditions, and for higher market prices. By replacing first-in-time with attachment, Alaska has made fishing safer and more profitable.

We now have similar models available to conserve many other natural resources. In Texas, for example, if you pump a lot of groundwater from your property, then your neighbor’s groundwater might drop, and their well might run dry. But we shouldn’t just say: “Too bad. It’s first come, first served. They should have pumped more.” Instead of encouraging overuse, and depleted aquifers, Texas could adapt attachment rules pioneered in other states that ensure sustainable groundwater management.

Mine suggests that first-in-time claims increasingly get “dismantled from within” today. Could you sketch a couple of “genius steps in ownership design” taken over recent decades to truly upend our sense of how first-in-time processes should play out — perhaps one private profit-seeking example, and one public policy-nudge example?

MH: Kids learn first-in-time from an early age, so it feels intuitive and fair to us. But more and more today, we see ownership redesigns that lead to first come, last served. I’ll give an example some readers may find familiar.

I took my family to Disney World, and stood in those endless lines. I thought: First come, first served. But Disney is actually the master not just of creating fun rides, but also of redesigning (quietly) how first-in-time works. Disney realized that when people idle in long lines, they aren’t spending money shopping and eating. So the company created the FastPass+ system, which means that, a few times during your visit, you don’t wait in line. You can wander around, buy a big turkey leg, some Dole Whip, and a lot of Mickey merchandise. Then later, at a fixed time, you use your FastPass+ for your preferred ride, with a very short wait. Families with little kids liked the system, but it was especially profitable for Disney.

Then Disney took the genius step. They created the Disney VIP Tour Guide. For three to five thousand dollars (depending on the season), Disney gives the wealthiest families a private guide who discreetly helps them skip every line on every ride, all day long. So if you want to go on Splash Mountain five consecutive times, knock yourselves out. Disney has to be careful, however. They don’t want to upset those families waiting patiently in line. So Disney makes it seem like VIP families are just exercising their FastPass+ option. Sometimes the guides even take their one-percenters through a side door or exit. Disney has split “first” into three separate groups: VIP customers who pay the big bucks, organized customers who plan ahead and spend time shopping, and lower-value customers left idling in lines.

That’s how first-in-time gets dismantled from within. And it’s not just Disney. It’s happening throughout our economy, as companies replace equality with privilege, time with money, first with last.

JS: You also asked about public-sector examples, Andy. Again, we see this playing out right now in real-time with COVID vaccines. Everyone agrees that frontline health workers should be first in line. But after that, who? The elderly? Prisoners? Teachers? Those with co-morbidities? What about service workers who interact with the public all day? Everybody has a claim to make about why they should move up in line. One reason this is such a mess has to do with sorting through all these completing claims. First is not a fact. It’s a choice. And very few states have been transparent about their choices.

COVID vaccines can take us towards possession claims. Possession-based ownership claims likewise have much historical, practical, and intuitive momentum behind them (while also no doubt bringing drawbacks for those previously disadvantaged, or for newcomers). Again though, why do we need to recognize possession claims as in permanent flux, in definitional terms as well as physical terms — with human history itself “a series of adverse possession conflicts writ large”?

JS: Across the vastness of human history, we’ve often seen the rule that might makes right. One empire conquers another. But today, we no longer tolerate that rule. For nation-states, we reject the adage that possession is nine-tenths of the law.

On the other hand, we still embrace this adage when it comes to private individuals. “Adverse possession” is an ancient legal doctrine that shocks our students whenever we teach it. If someone openly uses your land without permission, after a certain period of time it becomes theirs. Possession literally becomes ten-tenths of the law. Our law students say: “How could that be? That’s theft.” But here again, we need to think carefully about the goals of ownership design. We could paraphrase this ownership rule’s purpose as: “Look, we want this property put to productive use. If you didn’t even notice somebody openly using your land for 20 years, then you can’t expect the law to protect your claim either.”

Could you also describe how this plays out for more abstracted forms of land “use,” such as environmental preservation or climate mitigation?

JS: Sure. The problem here of course comes from adverse-possession doctrine getting developed long before we had these concerns about preserving wilderness and fighting climate change. Adverse-possession rules pose a real problem if the goal is to keep things natural.

Water law gives a good example. In the arid West, the rule for water was essentially first-in-time, first-in-right. The idea was that scarce water should be put to productive use. To stake a legal claim to water required you to openly divert the stream or river, to physically show that you had made beneficial use of it. Irrigation would redirect the water through ditches, sometimes taking it miles away (especially for mining). But what if today we actually want to keep this water in its natural stream? By definition, “prior appropriation” doctrine doesn’t allow environmental flows. Historically, keeping water in the stream or river actually was seen as “wasting” water. Thankfully that’s changing.

For one additional 21st-century take on possession claims, Jim already mentioned how digital licensing arrangements have displaced many preceding claims to possession (particularly those presuming a principle of exclusion). Do you see today’s sophisticated technologies of accounting also opening up any appealing possibilities for ownership to become more distributed, partial, granular?

MH: Physical possession taps directly our animal territoriality. These instincts run so deep that they actually predate humanity. When you hear kids on a playground saying “That’s mine!” they are invariably fighting over some tangible thing like a toy — never over a joke or story. The sense of possession hardwired into our brains has a strongly physical aspect.

Less tangible property (intellectual property, copyright, patents, all this stuff at the center of our online lives today) just doesn’t feel much like property to most people. But businesses are working to reengineer possession to activate our physical intuitions for this intangible world. That’s why DVDs open with those scary Interpol notices that “Piracy is not a victimless crime.”

So how does possession work in the “sharing economy?” Well, some people are claiming: “This is the end of ownership! Instead of needing to buy your own car, you simply can hail an Uber or Lyft.” But ownership is not disappearing in the sharing economy — just the opposite. Ownership is being concentrated in a smaller handful of increasingly powerful companies, controlling ultimate access to more of the basic services in your life.

As Jim mentioned earlier, you might own your iPhone, but if you fail to keep up with payments to your service provider, they can take away access to the information on this phone. They can shut you out from your entire life. That’s a whole different kind of concentrated ownership.

We’re also seeing big changes in our everyday physical world. I love to cook. With my old cookbooks, the stains on certain pages can evoke for me a whole phase of life. But I can’t imagine getting that feeling from scrolling down some webpage. Moving to a sharing economy brings a lot of wonderful benefits — but if I look into the crystal ball of human ownership, I see us losing touch with something very primal, almost spiritual, about certain material objects and the deeply personal associations they evoke. Who wants to lease a wedding ring, or rent a dog?

Still in those experiential terms, and with labor-based ownership claims likewise never stemming from static, neutral, self-evident definitions (instead always driven by struggles over who gets to decide whose labor counts), could you flesh out, for instance, how 18th- and 19th-century land grabs within the US premised themselves quite literally on a “reap what you sow” principle privileging European Americans’ claims over Native Americans’ claims?

JS: From the moment of its founding, America was embroiled in land conflicts. Some settlers bought land from the new states. Others bought this same land from Native American tribes. Who gets it? Everyone agrees first-in-time wins, but who is first? Why did Native Americans lose to Europeans?

Law students study this conflict through an early Supreme Court case, Johnson v. M’Intosh. The Court says that who counts as first depends on what type of labor people engaged in. Native American labor based on living lightly on the land didn’t count. For settler judges, the only “productive” labor that mattered involved clearing trees, building fences, practicing row agriculture — basically making New England look like old England.

Today we might see this reasoning as an artifice constructed to take land from Native Americans without compensation. And it was. But the Court grounded its decision in a certain consequential ownership story about productive labor. The same story would shape how homesteaders claimed much of the West, and later how America chose to award patents and copyrights.

Respecting a much more diffusive range of “reap what you sow” claims can bring its own social harms, say through the ownership gridlock that has come to characterize US biomedical research since the 1980s. In what ways have this industry’s ownership claims contributed to a less ambitious, less beneficial, openly rent-seeking business model?

MH: The “reap what you sow” ownership story that was so powerful in settling America’s frontiers also shapes the frontiers of ownership today for intellectual property. Our society rewards inventors with patents, and artists with copyright, based on a “reward for labor” intuition. But in the US, we now have too much ownership.

Reward for scientific discoveries, for example, used to consist in publication, recognition, enhanced reputation, tenure, maybe for some a Nobel Prize. America’s basic-science research took place in universities, with results shared widely in the public domain. This system produced many of medicine’s great advances over the past century — antibiotics, the polio vaccine, and so on. But starting in the 1980s, America shifted to a different model for basic science. We changed patent law so that university scientists could get more than just a published paper from their research. Now they could get a patent as well.

This ownership-design change was intended to spark more money flowing into basic research, and it worked. We got the biotech revolution. But one paradoxical consequence of creating so many basic-science ownership rights was that we got fewer new life-saving drugs. More money flowed into biomedical research, while less innovation that actually saves lives flowed out.

“Ownership gridlock” means that when you have too many overlapping ownership claims, resources end up getting underused, and wasted. Imagine a river, for example, with one hundred tollbooths between two cities, with each tollbooth operated by a separate company setting its own rates. You’d soon decide that it didn’t make sense to travel down this river to trade between these cities. That actually happened for centuries on the Rhine River in Europe. Too many owners meant too little trade.

The same thing happens with patents today. With too many owners (or tollbooth operators), you can’t reach an agreement to assemble patents for something really useful. You get gridlocked. Pharmaceutical companies initially interested in creating life-saving drugs turn to less ambitious research programs. Here our goal should not be creating more ownership, but smarter ownership.

For a parallel set of policy concerns: ad-hoc attachment ownership might allow for managing resources as productively as possible amid unanticipated moments of abundance. But could you give a couple examples illustrating what makes these attachment claims again less self-evident, fair, or stabilizing than they might first seem? And what 20th- or 21st-century examples most stand out for addressing, say, commons-tragedy scenarios in which everybody’s competing attachment claims would only ensure collective resource depletion?

MH: Attachment is the most important ownership story most people have never heard of. Here is just one tiny example. When you lean back in an airplane seat, why is the wedge of space you recline into “yours”? You’d probably point to the button on your seat, and say the button controls the wedge, and is attached to your seat. But the person sitting behind you has a different story. They say: “No, no, no. I had it first, first-in-time,” or “I’ve placed my laptop in this space, and possession’s nine-tenths of the law.”

These same disputes play out for all kinds of scarce resources. Think about land ownership. You hold a sheet of paper, the deed, basically for a two-dimensional stretch of surface land. So what else does this give you control over? What about wild animals crossing your land? What about wild plants or harvestable crops? How about the air above, or mineral resources down below? All of those claims are governed by this attachment principle, which remains much contested.

Today, we’ve resolved that airplanes don’t have to pay for flying in the airspace above your land. But how about drones flying one or two hundred feet above ground? How much airspace does get attached to your land? That’s an open question. Amazon and other delivery companies hoping to develop drone fleets care deeply about how this question gets answered. Claims to water or oil or gas flowing beneath the ground also stand out as some of the most economically consequential battles of our time. And what attachment claims can existing owners make to their land’s new wind or solar potential?

More broadly, in each of these cases, you also can see how attachment works as a “wealth magnet.” It automatically attaches additional resources to existing property holdings. That’s a hidden driver of wealth inequality in our society, a ratchet effect that makes the rich richer.

But attachment also has some very positive effects, which Jim will do a better job describing.

JS: Some of our greatest challenges in environmental protection come from not having enough ownership. If you own a wetland which provides flood protection to the community downstream, provides a nursery for fish to grow, or benefits the local fishing industry — how much economic value do you personally get out of this wetland? Probably not much, because you’re not allowed to build on it. Your wetland might bring vast social benefits, but you don’t own these benefits. You can’t charge for them. So it shouldn’t surprise anybody if many landowners opt to “develop” their wetlands however they can, even if we as a society lose out as a result.

That takes us to a cutting-edge 21st-century environmental tool, which in the book we call “as-if ownership.” As-if ownership reimagines attachment. One of the most powerful ways to reduce climate change, for example, involves protecting “carbon sinks,” often forests sucking carbon from the atmosphere. Deforestation of course has become a huge challenge in much of the world, particularly the tropics. So how do you design ownership so that landowners get more value from preserving their forests, rather than cutting them down? One way comes through treating this act of absorbing carbon and providing environmental benefits as something attached to existing land — so that it becomes a resource the rest of us can pay for.

One program that has become quite popular on the international scene, called REDD+, basically treats forest holders in Brazil, Peru, and Indonesia as if they “own” the carbon benefits that they provide to all of us. We pay them for this service. For the same reason, New York City has some of the world’s best drinking water, because it pays communities in the distant Catskill and Delaware watersheds for water-purification services that their well-preserved lands provide.

Self-ownership claims then speak even more intimately to foundational questions of what grants us our right to own property, to shape our destiny, to contribute to collective decision-making. Social norms centralizing our body as the core of self-ownership and the quintessential sacred resource might find themselves complicated, however, by 21st-century technological innovations making bodily resources more monetizable (potentially with greater public benefit) than ever. What could a profane economic marketplace proactively guarding the most sacred aspects of self-ownership ideally look like here?

MH: Self-ownership forms the core of who we are as individuals. No right is more fundamental. Self-ownership goes directly to America’s original sin of ownership, of brutal enslavement of African American people. That horrific history informs much of our thinking about self-ownership today — including how we understand the basic notion of “our bodies, ourselves.”

Today, we tend to frame self-ownership questions categorically. We have “on” and “off” switches, say for kidneys (sacred, no sale), for hair (profane, tradeable in markets). But we might do better as a society if we adopt a dimmer switch for self-ownership. The dimmer switch is more attuned to 21st-century resources derived from our bodies, but separable from them, like sperm and eggs (more precious than hair, but still tradeable with certain protections).

The dimmer-switch model might help for bringing together crucial concerns around sacred values (dignity, our fundamental equality) while at the same time addressing newly life-saving potential to trade new biological resources. So then the question becomes: can we create noncoercive markets that respect each individual’s essential dignity?

I’ll give a concrete example. Most states now allow paid “gestational surrogacy,” where a woman carries another couple’s child to term, though the egg doesn’t come from this woman carrying the baby. How should we think about one woman earning her living by carrying another couple’s child to term? Should we say: “No, this market should be closed off to protect our sacred bodies” or “Yes, this is a market transaction like any other”?

On/off thinking (profane or sacred, totally okay or totally not) misses the point. Dimmer-switch thinking instead might say: “We want to protect women who work as surrogates. We want to make sure they’ve received good counseling, and have arrived at this decision free from any coercion. We’ll also need to protect their interests, proactively thinking through in advance what happens if health concerns arise for the surrogate or the embryo. But with those protections in place, we actually can create something quite magical, with infertile couples now having the possibility to raise their own biological children.” That’s an important conversation to have.

By designing ownership to protect what’s sacred, while tapping the benefits of more profane market aspects, we can reengineer self-ownership for the 21st century, creating an enormous amount of good for infertile couples — while also making it possible for surrogates to earn a living in ways they prefer, perhaps over more dangerous or less satisfying jobs than surrogacy.

Here with family still in mind, could you also point to some huge societal costs of ineffective inheritance law? How do US designs for managing shared property contribute, for instance, to a broader racialized wealth gap, by diminishing the rural land holdings of African American families? And what makes the fractionation tragedy many Native American communities face “not only an ownership disaster but also a failure of judicial reasoning and political will”?

MH: Family ownership provides the sixth basic story everyone uses to claim everything. Wealth is on the move at times of birth and death, of marriage and divorce. For many African American families, land-ownership disparities that exist throughout life get terribly magnified at death.

After the Civil War, African American land holdings started to skyrocket, quickly becoming one of the most important tangible benefits of freedom for former slaves. By 1920 the US had a million African American farm-holding families, mostly in the South. But a century later, we only have about 19,000 such families — a 98 percent drop in African American farmland ownership. Much of this has to do with racialized violence and other forms of systemic discrimination, as well as a broader consolidation of American farmland. But one hidden piece of this story centers on a harsh set of rules shaping American family law.

Rural African American families often didn’t write wills, rightly skeptical of the (usually white) local lawyer. This meant that when landholders died, the states split these farms among their children. The children’s shares eventually got divided by the grandchildren. After a few generations, you might have dozens or even hundreds of partial owners for one single plot.

American law makes it virtually impossible to manage a piece of property split into small fractional shares. White Southern lawyers also soon discovered that they could buy just one one-hundredth or one-thousandth share from an heir who had moved far away (say to Chicago), then use that tiny ownership claim to force a sale of the whole farm. These farms got sold on courthouse steps, often in rigged cash-only auctions, to the white lawyer who bought for a lowball price. This combination of inheritance law and partition law (the ability to break up a co-owned farm) had a devastating long-term impact on wealth generation for African American families.

A similar tragedy befell Native American families. At the 19th century’s end, the US adopted a policy of breaking up Native reservation lands collectively held by the tribe. The federal government allotted these lands to individual families, with the goal of assimilating Native Americans into the dominant culture.

Initially, Native farmers lacked even the legal option to write a will. Their property had to pass through the law of intestacy (the law that applies when you don’t have a will). So Native American land automatically kept getting broken up, fractionated among heirs to the point where fertile farmland sat fallow, because there were hundreds or even thousands of fractional owners who could only hope to make pennies per year.

By contrast, what does every US citizen need to grasp about the stakes at play as a “billionaires’ club” strives to establish “a perpetual American aristocracy”? How in particular has South Dakota not only come to crush Switzerland and the Cayman Islands in tax avoidance and banking secrecy, but catalyzed a broader race-to-the-bottom dynamic eroding foundational legal conceptions of inheritance as a privilege granted by the state — rather than a natural right by family dynasty? And why does none of this correspond to “any intelligible version of American conservativism”?

MH: Few people realize that America has a separate, staggeringly unequal legal system geared solely to the super-wealthy (not the one percent, but the one percent of one percent). How is this possible? Because in the US, family ownership gets designed through state law — not federal law, not the Constitution. States like South Dakota have taken the lead over the past generation, allowing really rich people to stash their money there, avoid taxes, and dodge responsibilities like alimony, child support, and compensation for malpractice victims.

All of this money now legally resident in South Dakota (or states like Alaska and Nevada) avoids taxation in New York, California, Texas, Florida, Colorado — wherever these families want to live without paying their fair share of tax responsibility.

Nobody would call South Dakota’s position progressive, but neither does it align with any coherent vision of American conservatism: as a set of principles devoted to free markets, hard work, and opportunity. Creation of a new American aristocracy based on wealth (not on talent or effort) would have appalled America’s Founders.

To close then, what space exists at present (amid our lobbyist-friendly legislatures, and our harried judicial decision-making) for exploring more reflective, imaginative, far-reaching approaches to ownership design? Who should be working on that? With what kind of authority? And what role can and should individual citizens play?

JS: I’d actually push back on that description. We are seeing creative ownership design (not as much as we need, of course) in certain legislatures and courts. Still, Michael and I wrote this book to give readers a new way of looking at the world. Mine! shows that once you start exploring how ownership works, you start to see hidden features, and you start to recognize how these rules really should operate. You may start to feel like a fish who suddenly realizes: Oh gosh, this is water I’ve been swimming in the whole time! Once you can identify how ownership stories are used every day, you too can use them to be a more effective advocate in your own life and for the common good.

When we give talks on Mine!, we challenge our audiences to look at their newspaper’s front page that day. We guarantee you’ll find a story that snaps into focus if you understand the hidden rules of ownership. How can we be so sure? Because ownership rules touch on every aspect of our lives. They always have, and always will.

I don’t think you should look to any one source, such as legislatures or judges, for clever ownership engineering. You can find it everywhere.

MH: Let’s close with one last ownership story. Who owns your most intimate life online? Well, if you click around pricing airplane tickets to Chicago, over the next week you’ll see ads for Chicago hotels and restaurants popping up everywhere on the Web. These “clickstreams” are worth billions of dollars to Amazon, Facebook, and the Big Tech companies that track every move you make, every look, every like.

Clickstreams are up for grabs. Big Tech companies are claiming attachment: “We own your data because it’s attached to our apps.” That may seem natural, but we can fight back with other ownership stories. The clickstreams come from our bodies, and reflect our self-ownership. We were first-in-time. Our productive labor generates the data.

We want readers to feel empowered to take back control over ownership in their lives — as consumers, as parents, and as citizens. Once you see how ownership really works, you can’t un-see it. And once you do understand it, you can be a more effective agent for change.