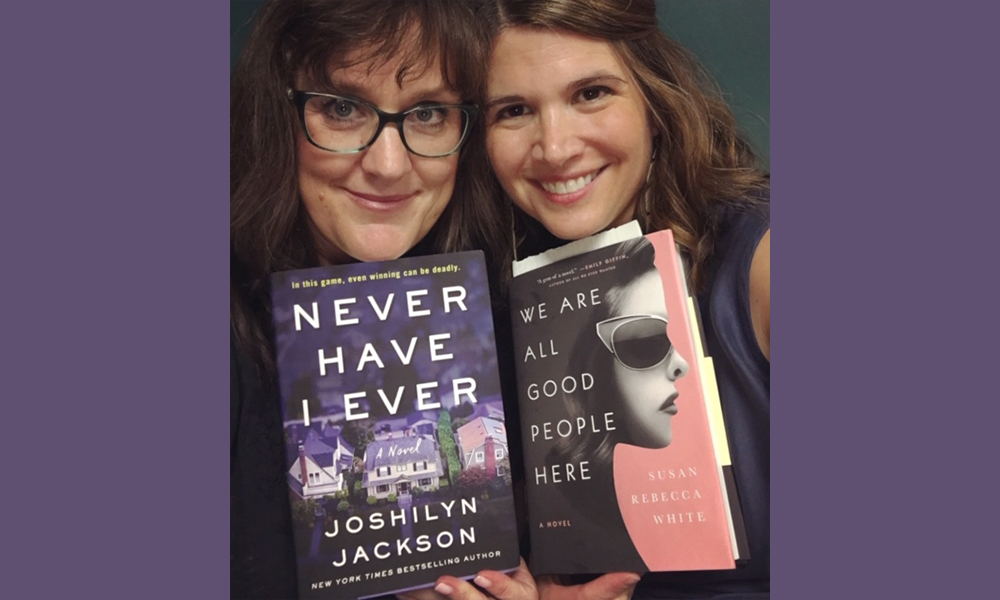

I knew of Joshilyn Jackson long before we met, having read all of her books, but the first time I saw her in person was at the 2008 Decatur Book Festival, where she gave a presentation on The Girl Who Stopped Swimming. In her talk, Joshilyn revealed that she modeled the main character, Laurel, on Pamela Allen, a fiber artist who renders domestic subjects through a feminist lens, including touches of the macabre. After Joshilyn completed the manuscript, she commissioned Ms. Allen to create a quilt similar to one Laurel might have made. The finished quilt shows a bride with seed pearl daisies on her shoes, only one of the pearls is an actual human tooth. The quilt hung behind Joshilyn during her entire presentation. It was so wonderfully odd, and Joshilyn was so raw and real, that it felt as if she were talking directly to me, despite the fact that there were over 500 people in the audience. I’m pretty sure everyone felt that way.

The next year, my first novel was published, with a second one following shortly thereafter. (The upside to having been in an unhappy marriage — I wrote a lot.) In 2010, both Joshilyn and I attended an awards banquet for Townsend Prize nominees (an annual award given to a Georgia author). Neither of us won. Afterwards, we went to dinner. Joshilyn was warm, funny, and authentic. Having read both of my novels, she told me that she really liked the first, but thought I had hit it out of the park with the second. For a woman of such immense talent to be saying such things about my work — it was better than any prize I might have taken home.

Soon enough, I was in the middle of a divorce. People say odd things to you under such circumstances, either explaining to you why things aren’t so bad, or indicating that you will probably die alone, the cat nibbling on your decomposing body. During that sad time, Joshilyn and I met for lunch at Leon’s, a favorite spot of ours in Decatur. I was a little worried about what she might think of my divorce. A person of great faith, she took her wedding vows seriously and considered her husband, Scott, her best friend. I shouldn’t have worried. I told her I was a mess, and she said something to the effect of, “Well, of course you are. You are going through something really, really hard.” Embarrassed — because, at the time, I was not someone who spoke openly of my faith — I asked if she might keep me in her prayers. “Oh, bunny,” she said. “You’re already in them. Every day.”

I still don’t know if I believe in intercessionary prayer — but I took great comfort in knowing that Joshilyn was concentrating on me every day, wishing me peace and resolution.

Since then, Joshilyn and I have read and critiqued each other’s manuscripts, talked at length about our faith and how it propels us to action, gone on writing retreats, introduced each other to new foods and restaurants, and, in general, sustained a friendship. In a world where it is too often assumed that if you are progressive and intellectual, you are also skeptical of religion, particularly Christianity, it is regenerative to have found a fellow pilgrim in Joshilyn, the woman I once admired from afar who is now my dear friend.

¤

SUSAN REBECCA WHITE: I had a professor in grad school who suggested that most artists are driven by one “essential question” about life that he or she is trying to work out. Thinking about the nine (nine!) novels you have published, I’m wondering if there is a singular question — an essential question — that’s behind all of them.

JOSHILYN JACKSON: It’s hard to fit nine books under a single lens. I have to go very wide angle; it’s the mechanics of grace. I don’t understand grace. I don’t think anyone fully understands it. My books are often an exploration of an aspect of it. Like in Never Have I Ever, I’m interested in forgiveness.

Who owns our forgiveness? God, or the people we’ve wronged, or society at large, or ourselves, or our families? Who can offer us absolution? Are you allowed to remake yourself, be so truly reborn that your past is wiped away? In which case, it becomes a secret that can be used against you…It was especially fun to look at this via psychological suspense.

That’s a really great question, so I’m going to send it back to you…

I love that you explore questions of grace and forgiveness and how complicated and nuanced both are. I’m really interested in Bonhoeffer’s idea of “cheap grace,” which, as I understand it, is when absolution is offered simply if someone says, or is forced to say “sorry.” Meaning, one is “forgiven” without reflection, without repenting, without attempting to repair the breech. I would say that much of white America’s attitude toward our history of slavery is an example of “cheap grace” demanded.

In terms of a question running through of all of my novels: I think I’m always wrestling with the question: “To whom do we belong?” Who is our family? Is it biological or chosen or something else entirely?

My family of origin formed in the chaos of divorce and has remained fractured, albeit beneath a veneer of “Everything’s fine! Nothing to see here!” All of my siblings are half-siblings to me, and they are all halves- and steps- to each other, and my parents, who got together in a whirl of romance in the wake of divorces from their first marriages, tried really hard to make everything okay and equal and fine. But there were a lot of fissures, and there was an unspoken rule that we were not to point them out, not in any serious way. As the only biological child of my parents, I think I felt safe enough to point out the cracks. But at a certain point, it became healthier and more productive to work out my questions regarding family through the guise of fiction. With the exception of A Soft Place to Land, which is the closest I’ve ever come to writing directly about my family of origin even though the events contained within the book are wildly invented, I don’t write about families that much resemble my own. But most of my characters do struggle with their birth families in some form or another, and often feel exiled, and are working towards finding themselves in relationships that feel something like home, whether those relationships are rooted in biology or not.

I see this in my books, too! It’s one of the reasons your work speaks to me. I’m very often writing about nontraditional parent/child relationships especially. I’m so interested in people with no biological imperative who choose to love someone sacrificially — in such a way that the person’s life suddenly becomes more important to you than your own. People do this all the time, deliberately and inadvertently, and I always find it so fascinating and beautiful.

I love that about your books. Immediately, my mind jumps to the non-biological mother-daughter relationships in Between, Georgia and Never Have I Ever. Did you know when you were writing each of your books that you were wrestling with questions of grace and sacrificial love? Do you write with a theme in mind, or does a theme emerge through the process of writing?

I know I write character driven fiction; my books begin with a character. I invent a person who interests me. They are always very different people, but the things they have in common are most of them are deeply flawed and most of them want to be decent human beings. Not all of them are decent human beings, not by a long shot, but most of them want to be. Or they come to want to be over the course of the book.

I’m interested in people who want to connect and be better and overcome their hardest challenges and make up for their mistakes and their acts of deliberate evil. Character is how I find theme, as my characters are embodiments of the questions that drive me. How forgiveness works, how redemption is shaped, and how we are called to it.

At a certain point I’ll begin to understand clearly what I’m wrestling with and that’s when craft comes in as I begin to shape the images and ideas more deliberately, but it starts with a human being for me, always. The stories that these characters play out are how I explain the world to myself… I don’t have a lot of patience for those old-school sermons where there’s three F’s, like faith, forgiveness, and funky town. But I’ll sit and listen to parables endlessly.

I’m character-driven, too. I start with a voice. The voice takes me to the plot.

That said, if I’m honest with myself, one of my initial motivations for writing We Are All Good People Here was that I wanted to prove to myself that I was nothing like the militant antiwar group, Weatherman! Let me backtrack: Back in 2003, I was in my 20s, living in San Francisco, and pretty politically engaged. I attended a lot of antiwar marches, believing the Bush administration was using spurious charges of WMDs to coerce us into an unnecessary second war with Iraq.

Around that time, I saw an excellent documentary called The Weather Underground, about this militant offshoot of Students for a Democratic Society, an antiwar student organization. The members of Weatherman were so outraged by the Vietnam War abroad, and race relations at home, that they declared war on the US government, went underground, and set off “symbolic” bombs at important places, such as the Pentagon. And most of them got away with it. The members were all white, from wealthy families, and buffered by privilege.

I drew parallels between the US involvement in Vietnam in the 1960s and 70s, and our involvement in Iraq in 2003, and I agreed with some of the Weatherman’s ideology. But their militancy really freaked me out. I wondered, “Could I have been involved with them had I been young in the late 1960s?” I think when I first started writing the novel, I hoped to draw a clear line between Good Activism and Bad Activism, so I could label mine “good,” theirs “bad,” and stop fretting.

As I wrote We Are All Good People Here, the lines of good and bad activism blurred. By the time I finished, I was re-thinking everything, and re-thinking the binary framework I began with. And the religious part of me would posit that the blurring of lines is a holy thing. Anytime you think you’ve got someone nailed, pinned down, figured out, and ready to discard — you are not operating from a place of grace.

Since we’ve already discussed grace, forgiveness, and “the religious part of you,” let’s just jump into that subject you’re not supposed to talk about in polite company: religion. You and I both write Christian books. Albeit, Christian books that no “Christian” press would touch with someone else’s 10-foot pole. But I see your faith so deeply embedded in your novels… Especially in We Are All Good People Here. What does it mean to you to be a Christian writer whose work reads as secular or in some cases even blasphemous? Do many of your readers recognize you as a Christian writer?

Not even someone else’s 10-foot pole? I’m oddly flattered! I don’t really think of myself as a Christian writer, but rather a writer whose worldview is Christian, albeit it’s a progressive Christian worldview that some of the more conservative members of the faith might find apostate.

But yes, I would say that all of my novels are grounded in the assumption that God is love, that love is abundant, regenerative, and eternal, that love is not coercive, that love has the potential to transform even the most jaded among us. That love can squeeze inside a prison cell, can squeeze inside the hearts of people we might think are beyond redemption. That death is necessary, and death is awful, but it is not the final story. That reconciliation is the final story. On the flip side of that, my novels are grounded in the understanding that every single one of us possesses the capacity for both cruelty and compassion. The potential for evil — or just carelessness, meanness, blindness — resides within us all. Which means people in my books do some terrible things.

How about you? Do you identify as a Christian writer?

I think I do. So. Boldly. Yes. I know my writing and almost everything else that I do deliberately happens through the lens of my faith. That said, I am an unrepentant universalist. Christianity holds great meaning and makes sense to me as a narrative because I was raised in it. In the South, we still practically put it in the water, and it was even more saturated when I was growing up. My faith connects me to my family and to a moral center. That said, I don’t think it’s any more valid than any other connective path to God.

Sorry to interrupt — but I want to give a quick “amen” to recognizing that our particular Christian path is just that, our particular path. And, to recognizing that where we were raised often determines our faith. I think if one is raised in the “Christ-haunted South” as our beloved Saint Flannery O’Connor put it, Christianity is pretty hard to escape, whether you’re experiencing it as an outsider or an insider.

Yes! So. I do think of myself as a Christian writer, but yes, more conservative Christians might consider me apostate. And crass. I sometimes get angry letters because in a lot of my books I am critical of the church. But the way I see it: I’m part of the church. It’s my responsibility to be critical. If you stand outside, if you do not love it, if you do not want the best for it, then why should you have a voice in how it is shaped? We inside must be vigilant and critical and aware. Anything that is powerful can be subverted and faith is very, very powerful. It can be used to gain agency and control over other people, so it attracts wolves and cannibals, pushing Jesus narratives that can be dangerous. Like the Jesus who wants you to have a Cadillac. Or the Jesus that wants you to only be around polite white people who don’t say bad words. I’m much more interested in the Jesus who ate dinner with prostitutes and tax collectors and died for his ideals. That’s the Jesus I see in your work, too.

Yeah, I’m definitely not interested in Cadillacs, piety, or creating a false god out of, say, corrupt politicians, but I’m very interested in the Jesus who goes to those on the margins. Has your faith led you to places you might not have otherwise gone, and has that affected your writing?

For seven years now, I’ve been on the board of an organization called Reforming Arts (RA), and through them I teach as a volunteer in Georgia’s women’s prisons. Never Have I Ever actually began with a conversation I had with a student there.

I know this woman well. She is brilliant and outspoken and warm-hearted and tough and a great role model. While incarcerated, she completed a college degree from Life University with a 4.0. That’s a better grade point average than my son, I will tell you that!

Recently, she came up for parole. She has been in prison for more years than she was alive before she was incarcerated. She went in a very young mother and is now a grandmother.

She said to me, “When I leave here, when I try to get an apartment or a job or join a community, they’re going to know the worst thing I ever did before they know anything else about me. I have to carry it around and show it first. I don’t even remember being the person who came here. I’m scared no one’s going to look beyond my past. I’m afraid I’ll be defined solely by my worst, darkest moment.”

I think we all have that fear — does our worst moment define us? That was the jumping off point for the book.

I know you visit with undocumented immigrants and asylum seekers in detention. Have those visits influenced your writing?

A couple of years ago, one of the ministers at my church urged all of us congregants to visit the immigrant detention center located in rural Georgia, saying that doing so would “change us.” After that sermon, I kept hearing this little voice in my head saying, “You need to go.” But I’ve always feared imprisonment. I did not want to enter a building surrounded by barbed wire. I did not want to talk to a stranger through a plexiglass window. Hell, I didn’t want to drive the two hours it takes to get there from Atlanta. But, I kept hearing that little voice, and I felt that if my faith meant anything, I needed to heed it.

I’ve now visited the detention center four times, and I’ve made a commitment to continue going twice a year. It’s sad, and it’s hard, but I’m glad to do it. And in addition to speaking with detained immigrants, I usually end up talking with someone from the SCHR (Southern Center for Human Rights), who is doing pro-bono work there. And that’s a neat little bit of synchronicity because Daniella, one of the central characters in We Are All Good People Here, ends up working for the SCHR, so it’s kind of like I’m talking to her.

But here’s the thing: Unlike the SCHR lawyers I meet, I’m not helping anyone be released. I’m not changing the system. At best, I’m showing humanity in an often-inhumane system. And the detainees allow me to come more fully into my humanity. They demonstrate so much grace in being willing to talk, to share themselves with me, given all that they have been through. They help release me, just a little bit, from the blinders of privilege that I too often wear, blinders that allow me to ignore or dismiss any reality that is too uncomfortable, painful, or inconvenient.

Will you talk a little more about your experience teaching in prisons? Has it influenced your writing and your worldview?

Yes. I can see it in the books I have written since I started working with RA. Never Have I Ever, as I said, was a direct result of an interaction with a student.

The first book to feel RA’s influence was The Opposite of Everyone. It is structured like a legal thriller, and it’s narrated by a lawyer who came up in the foster care system because her mother was incarcerated. The separation of families and the often capricious ways those families are kept from being able to connect with their incarcerated loved one is terrible. If we’re interested in rehabilitation and stopping recidivism, then we have to do all we can to facilitate strong community ties so there is a support system when the incarcerated person gets out. Community is everything.

I think that what you just said, “community is everything,” is universally true. To lose our community costs us everything. But being in community can be such a challenge, because it often means engaging with people whom we find difficult. But I think God gets psyched when we find ways to be in relationship with all of the people and beings who are placed near us in life, whether we are naturally drawn to them or not. Meaning, God gives us a celestial “high-five” when we visit our elderly neighbor, nurse our dying cat, go to dinner with our Trump-loving relative. (Which is not to say I’m an apologist for Trump supporters. But you don’t jettison the person in an attempt to reject the ideology.) Now, if someone is abusive, I am not advocating sticking around and taking the abuse. You engage with that person from far, far away. You say a little “loving kindness” meditation toward them, and then let go. Or not. (I am not an advocate of forcing anyone to offer forgiveness.) But, I think there’s something holy about trying to see past our immediate political or religious or class differences. Beneath all of those signifiers, all of us are made of blood and bone, and all of us are only on this earth for a brief moment. So, why spend the time nursing bitterness and division?

To all this I say a great AMEN. You and I both create all these flawed people who want to be better, who want to be good, and who fail in multiple ways. Neither of us writes fables or sermons disguised as stories. We both let our characters be human beings, and we don’t draw easy conclusions and then end with a finger wag and a shiny, tidy little moral. That said, writing and reading are both the deliberate practice of empathy.

Years ago, in an awesome indie bookstore in Los Angeles called Book Soup, I saw a card taped to a shelf. It was an employee recommendation, and all it said was, “Read Graham Greene; become a better person.” I love that semicolon. Yes, Bookseller, these things are connected. Maybe you and I both want to write a path to being better people. If so, I can think of worse ways to spend our single, precious, unrepeated lives.