What allows certain drowning communities to start seeing options again? What causes certain immigrant parents to pause (and contemplate) mid-yell? When I want to ask such questions, I pose them to Representative Ilhan Omar. This present conversation focuses on Omar’s book This Is What America Looks Like: My Journey from Refugee to Congresswoman. Omar, the first Somali-American legislator in the United States, currently serves as the US Representative for Minnesota’s 5th district. In 2018, she became one of the first two Muslim women elected to Congress, as well as the first woman of color to serve as a US Representative from Minnesota.

Representative Omar and I spoke in mid-June. She has since lost her father, Nur Omar Mohamed, to COVID-related complications. LARB expresses our condolences to Representative Omar, who describes below having “A lot of my dad and his values and his sense of what it means to be a decent human being run through my blood.”

¤

ANDY FITCH: Could we start with your personal sense of duty “to call out the lack of awareness about the disintegration of civilization…possible anywhere”? Could you first flesh out the unnerving recognition, as an eight-year-old watching the Somali Civil War enter your community, that: “The adults didn’t know what was happening, even though I felt they should…. I kept hearing them say…over and over: ‘I don’t understand how everything just turned’”? And could you describe, today, never wanting to be the adult who says that?

REP. ILHAN OMAR: I sometimes do find myself today actually being the adult who says that, who asks what’s happening with our country. But in times of unrest, you also hear a lot of people say: “I just don’t know how we found ourselves here.” That’s a slightly different point. To me, that response typically suggests two things. First, this person probably had some sense of comfort while others struggled all around them. If you had been paying attention, you probably wouldn’t be so surprised. And second, this person probably hasn’t connected enough with the distress that other people are feeling.

At one listening session we held after Minneapolis police killed George Floyd, Ayanna Pressley said something like: “Let me be clear. We won’t see the end of unrest until there is no unrest.” I hear in Representative Pressley’s words a powerful reminder that we’ve gotten pretty good at figuring out how to go back to normal as quickly as possible. Even with COVID, we’ve learned how to do a daily check-in with the people in our immediate lives, to make sure everybody’s doing okay, to see what kind of distress they may be experiencing. But we might miss some of the bigger systematic failures of our society along the way.

So when I looked back retrospectively at what happened in Somalia, I could see how this daily grind and obsessive focus on ourselves and our immediate family often overshadows everything else. It feels like enough just to make sure those daily needs get met. When you have a semi-functioning society, everything else sort of stays in the background. You might see homeless people on the sidewalk, and maybe you do what you can — though you don’t often dig into the systemic failures that led them there. You might see a strange police interaction, or even a killing, and never move past the thought: Somebody should do something. But we do have, I believe, a basic duty to be the Good Samaritans who could never look away, who could never fully settle in and just watch those kinds of injustices happen.

This book’s early chapters stand out as some of the most powerful personal narrative from a political officeholder that I can remember coming across. For one quick sample, I just couldn’t believe all that gets conveyed in this understated description of initial refugee life in Kenya: “For the first year and a half in the camp, my grandfather and dad walked around like zombies.” Or then on the following page you write: “Eventually we adapted to our new lives and came out of our funk. Not only did the adults begin to dream… about what an exit from Utange might look like, but they also started to improve life in the camp.” So how did that collective transformation come about? And how did taking part in these communal traumas and renewals help to shape not just your political values (a lot of people have political values), but your whole political life?

When you live within that kind of communal trauma, you almost can’t recognize it. You can’t get any perspective from outside of that space. Outsiders might look at a community experiencing poverty and trauma, and ask: “Why can’t they come up with any solutions to fix this?” But when you find yourself stuck like that, when you’re basically drowning, you often just can’t see any other possibilities.

My father and grandfather, for example, had grown used to a feeling of control over their lives, and of being able to take care of their family. Suddenly, in this much more vulnerable situation, they didn’t really have a clear sense of how to make our lives any better. For a long time they just stayed stuck like that. Then eventually, this shift took place. The gates somehow opened a bit. We started to see a way out. When you undergo that kind of transformation, you maybe still don’t know how to change your circumstances right away. But you begin comparing options again. You can envision how things could change. You don’t just resign yourself to your current life.

Experiencing that kind of transformation does inform my political life. I’ve never found comfort in being comfortable. I’ve always sensed that when you start normalizing big parts of your life, when you set aside the constant need for reflection and analysis and renewal, then you’ve probably normalized something not very normal [Laughter]. So my activism and advocacy and now my legislative work really start from examining systemic ills we’ve normalized for too long — and which bring us the kinds of unrest we have right now. We often end up in this sort of trance phase of just getting by and getting along. Nobody likes being jolted back to the reality that things are not normal. You can face severe pushback for saying: “No, we can’t accept this.” A lot of people will say right back: “Well actually, I’m doing fine. So I don’t want to talk about that right now.”

In terms of daily injustices we do and do not acknowledge, your dear aunt Fos dies of malaria at Utange. That kind of event doesn’t make international news coverage in the US. But why do your American readers definitely need to hear about it?

Well, I almost didn’t put that in the book. That story still hurts too much. I didn’t really want to revisit it. But mid-way through work on this book, one day in Minneapolis’ Riverside neighborhood, I talked to a mother who recently had lost her child to violence. And she just kept repeating: “I ran away with him so he could be safe.” And I couldn’t stop thinking about my aunt running away with us, particularly with me, to help keep me safe. Death found my aunt during that time. So I do want readers here to know you can’t just think about war in this unilateral way — as a horrible situation that hopefully people can run away and escape from. Often in war you can’t flee and get out of danger. You just move on to new dangerous and difficult situations. Reaching a refugee camp might save you. But it also might not. It might even have more dangerous conditions.

People often have to flee from a warzone, without knowing what they’re fleeing to. They just know they have to get out. So we might easily pass judgment when a young girl and her father die at a border. We think: How irresponsible could he have been to put himself and his daughter in that position? But he might have sensed a lot of hidden dangers along the way, though still had no better option.

So I do want Americans to have a bit more sympathy for the kinds of horrible decisions people must make in these terrible situations. And even in my own life, I struggled for a long time with lots of anger about certain choices my family made. Though then as an adult and mother of two I went back to one of those refugee camps. I met mothers and fathers who had to make decisions like my family made. I heard about how they too lost family members along the way — but all in an unceasing effort to care for their families.

While still in Kenya, your grandfather suggests that: “Only in America can you ultimately become an American. Everywhere else we will always feel like a guest.” When then arriving in the US, you experience “a breakdown for the refugee in the separation between what you are told and what is real.” Why should all Americans share their communities with New Americans — and not just because some of us consider it morally correct to welcome immigrants or refugees into our midst? Why does America simply not function right without New Americans’ fresh, clear-eyed visions pushing us all forward?

Yeah, this gets pretty complicated. In the book I talk about Americans working really hard to export a certain image of ourselves, but often not working as hard to make that image our reality. I’ll probably never get over this strangeness of Americans taking so much pride in persuading other people to think we’re great — but then just stopping right there. We hold onto this idea of America as the place where hardworking people can come and grind out multiple shifts every day, and ultimately fulfill their dreams and buy a home and send their kids to school. And even today we do have some New Americans renewing the American dream in this way. But ultimately, with almost every generation of New Americans, they’ve eventually adjusted to this life of haves and have-nots, to an America that doesn’t treat all Americans well, or even fairly. They get used to America’s basic constitutional rights not applying for everyone.

Thankfully, from my earliest discomforts onward, my father and grandfather never told me I should just get comfortable. They told me I had a place in fighting for that better America for everyone. The greatest form of appreciation that a guest can show comes from doing their share of the cleaning up and the fixing up around the space (and sometimes becoming more than a guest, right)? And I do believe that when New Americans arrive, they bring that sense of responsibility we all should feel. They don’t see achieving the American dream for themselves as enough. They can still see the need and the basic requirement to work on forming a more perfect union.

For your own life growing up in America, I found particularly moving how, before you become a catalyzing (and unwittingly polarizing) symbol in our national politics, you become such a presence for your dad, who would “catch himself mid-yell… as if… having a back-and-forth with himself.” Could you describe your own lived process of coming to understand your dad’s experience in the US?

My father had the misfortune of raising me in America as the only child still living at home. And I say “misfortune” because I wasn’t the easiest adolescent to raise [Laughter]. But we also always have been very close. A lot of my dad and his values and his sense of what it means to be a decent human being run through my blood.

My dad had the kind of struggle many immigrant families have when raising children in the US, and wanting them to succeed here, but also to hold onto certain cultural values. Strangely though, some of the Somali values still left in my dad (especially around the roles of women) hadn’t shown up in him before we came to the United States. And when I’d literally see him pause in mid-yell, and start contemplating, the interesting part (I realized much later) was that he wasn’t contemplating the values that he himself had expressed in Somalia. He was contemplating the values of more traditional Somalis. He was struggling in the face of all his family and friends and the tight-knit Somali community telling him his liberalism had been a big mistake. He was struggling with having set a strong example for me of doing the right thing and not worrying too much what people think of you — but now those voices and comments and critiques did get to him.

At this point, we’ve had a lot of conversations about those earlier years. When I can kind of jump back into my dad’s brain for all of that, I also can see him just having a normal fatherly worry about doing the best job he could, to the best of his ability — while never feeling fully confident that his parenting skills would allow him to navigate this new space.

Okay, now for some trickier parts of this book’s political analysis, could we start from your demoralizing encounters with, for instance, a clique of dominant Somali Americans considering themselves the community gatekeepers, and the guides for a lockstep voting bloc? Outsiders might assume that, as a Somali-born politician, you must have had an easy time wining in your particular district. Why could that assumption not be more wrong? Why should we not trust any self-appointed spokespeople claiming to have a whole community’s votes “in the bag”? And why should we never tolerate such blatant disregard for democratic participation in the first place?

First, as you suggested, that assumption about my district’s demographics just doesn’t fit the reality, or the actual place of Somali voters. Although we have the country’s highest concentration of Somalis, that doesn’t mean anything like a majority. It means something closer to five percent of this district’s electorate. And as you know, from reading this book, I definitely did not receive that entire Somali community’s support.

Most definitely not.

And that’s fine with me. We represent districts and constituencies — not demographics. But a second misconception comes when people think some sort of huddle took place among a handful either of the Somali community’s leaders, or the Democratic Party’s leaders, who then anointed me to run. Again, the trials and tribulations of first winning my state House seat and now this seat in Congress should make it perfectly clear that something quite different happened.

I’ve never been able to reconcile that idea of powerbrokers (deciding for the rest of us who should and should not have influence) with my basic understanding of democracy. I mean, how does that kind of control over a whole community exist alongside “one person, one vote”? How does a true democracy work unless elected officials have direct access to their constituents (and vice versa)? I’ve worked really hard as a political organizer, and now as an officeholder, to sidestep that whole traditional approach to politics. I’ve put my faith in seeing what American democracy looks like when elected officials actually engage the people, and hear from voters themselves what these representatives should fight for. I definitely see possibilities to take shortcuts, and to make backroom deals that you might even believe will help your constituents. But I don’t see how that helps to build a healthy democracy. I just see that aloof approach contributing further to the low voter turnout we often have in many communities around our state and country.

To close then, what’s it like to recognize that so many colleagues in Congress have not experienced the kinds of life challenges that honed your own commitments? How does that difference from other legislators shape your personal position that: “if you weren’t constantly worried about the work you were doing on behalf of the people you represented, then we had a problem”? And how can that type of candor today help to push us beyond some of our most persistent political impasses?

To be honest, it’s challenging at times. But throughout many of the immigration and border debates we’ve had, I’ll get the opportunity to really talk to my colleagues. I’ll point to all the ways that we expect other countries to embrace and care for the people coming across their borders, and the ways in which we ourselves don’t live up to those same values. And I appreciate having colleagues who hear me out on those questions.

I also remember traveling with Speaker Pelosi to Ghana. We talked about some of the young people we might get a chance to meet. Speaker Pelosi told us about her experiences visiting Darfur, and the vacant expressions she saw on some of the children’s faces. She said something like: “I wonder if I’ll ever get a glimpse of what those faces look like today.” And Karen Bass said: “Well Ilhan’s one of those kids. Look at her.” And even for myself, I never want to lose sight of that. We all know the experience of staring at these photos of devastated children, and not feeling capable in that moment of doing anything but wonder: What’s their life like today? But I literally am the living, breathing picture standing right here. And things turned out alright for me because certain people invested so much (sometimes everything) to give me a second chance at life. That’s what our commitment to each other can accomplish. That’s how we preserve a sense of humanity through even the hardest challenges.

Speaker Pelosi and I sat up for two more hours that night, talking about that look she had seen on children’s faces in Darfur, about how that look eventually could transform into a smile — and everything that has to happen along the way. And I hope that talk stays with her, as it does for me. I hope that when she finds herself advocating for a policy in regards to immigration or refugees, she remembers those vacant faces. But I also hope she can picture the smiling face of her colleague, who was that kid, and who then had the good fortune to experience a much better life, because so many people never gave up on making sure this could happen.

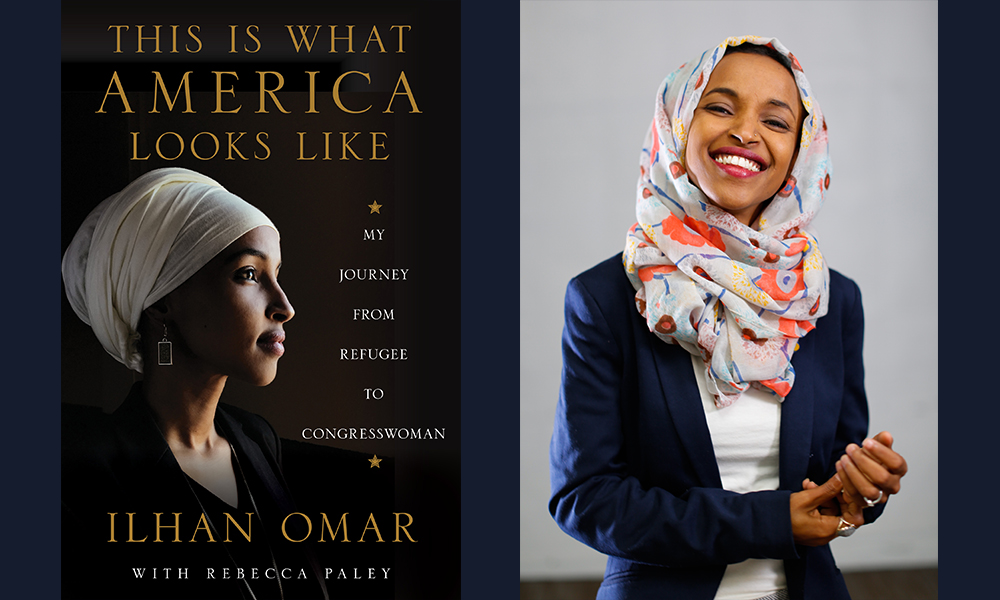

Portrait of Rep. Ilhan Omar by Erica Ticknor.