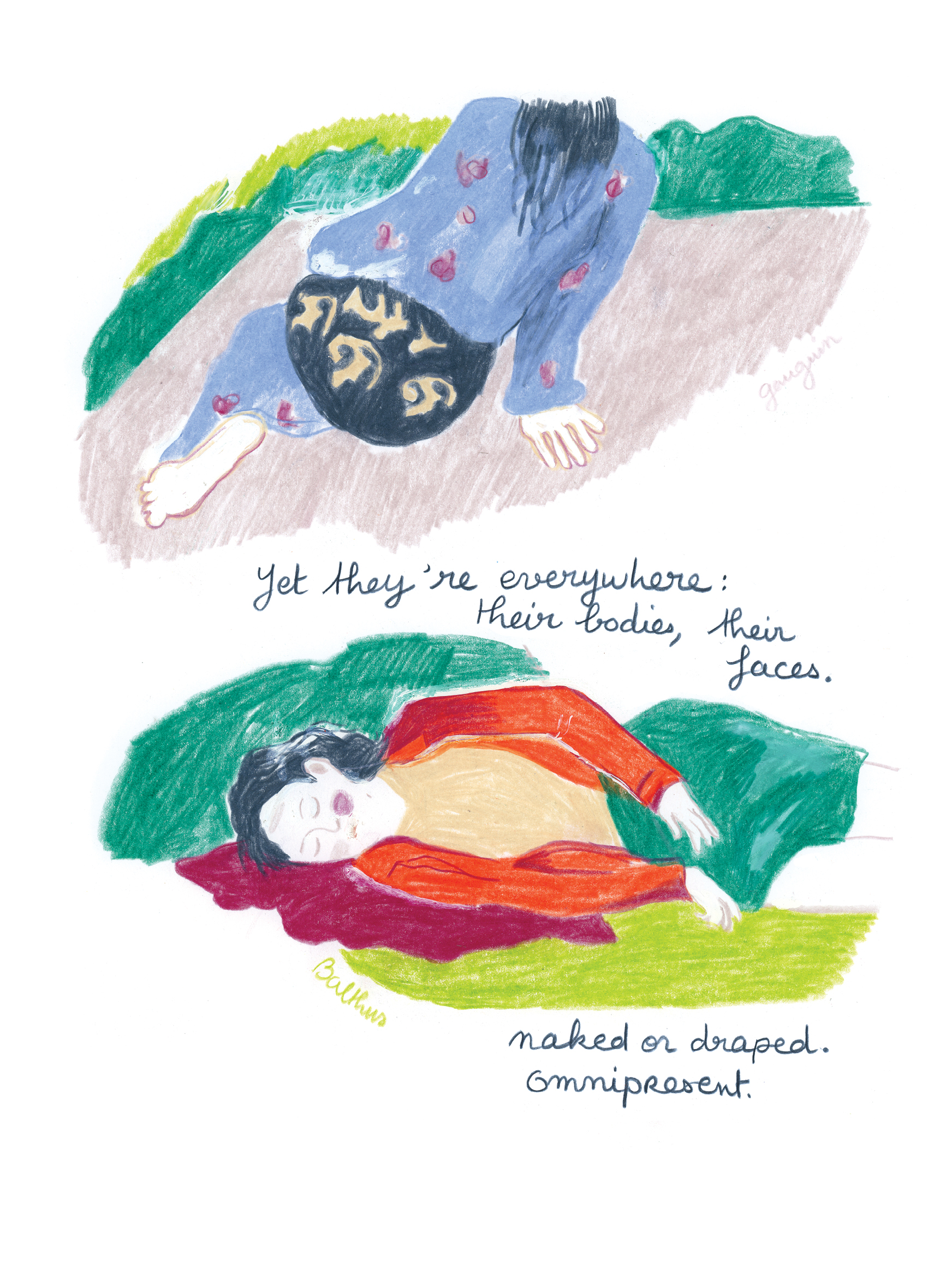

Julie Delporte set out to make a book about the Finnish writer and artist Tove Jansson. It turned into a skipping and rich meditation on the experience of gender. This Woman’s Work perceptively confronts the prejudice attached to femininity with colored pencil drawings of Red Riding Hood, memories of Delporte’s own trauma, and dreams of polar bear battles. Delporte’s journal-like entries are also in an active dialogue with a legion of feminist heroes, including Virginie Despentes, Annie Ernaux, Elena Ferrante, and many others.

There is a conversational ease to the narrative method of This Woman’s Work that disarms the reader and leaves them vulnerable to flooring realizations, or even just new questions. I wrote to Julie Delporte to ask her about how she created this book.

¤

NATHAN SCOTT MCNAMARA: While This Woman’s Work doesn’t explicitly engage with the Kate Bush song it borrows it title from, it’s a fitting homage. Could you tell us about your history with Kate Bush’s music?

JULIE DELPORTE: One of the translators of the book, Aleshia Jensen, found this title. The original french edition had a different title which made reference to a French grammatical structure (the masculine takes over the feminine, something that literally every french kid learns at school) and couldn’t be translated. I like the English title because it adds one more inspiring woman to my research of desirable feminine identities — Kate Bush joins Tove Jansson, Chantal Akerman, Paula M. Baker, Geneviève Castrée, and other women present in the pages of the book. I like Kate Bush’s music, though I don’t know it really well, but it made total sense that the title references another woman’s inspiration, whether it’s my translator’s or the reader’s. The goal of my book is for it to be about something larger than myself. I wanted to ask readers: “this is what it’s like for me, was it like this for you?” The title Aleshia Jensen found makes me think of the idea of women as a working class… This Woman’s Work talks a lot about maternity — a subject I never planned initially, and only discovered when I finished drawing the book — which is considered the work of women above all. In Caliban and the Witch, Silvia Federici addresses it, explaining how capitalism was partly built on the appropriation and exploitation of the reproductive work of women.

Both in the book itself and the acknowledgements that follow, you reference “feminaries” such as Tove Jansson, Virginie Despentes, Amy Berkowitz, and others. Could you tell us how those writers/artists arrived in your life and how their work moved you at the time?

The word “feminaries” is a neologism from a Monique Wittig book (Les guerillères), where it is defined as a book that a group of women use as a kind of bible. In This Woman’s Work, the “Feminaries” becomes all the books written by women, all the books who started to work for me as alternative bibles from the white male occidental perspective I was taught until then.

I realized that during my scholarship, the only book written by a woman I studied (and I was in a literature program) was by Agatha Christie when I was around 12 years old. You would think they would have made us read at least Virginia Woolf book or a Marguerite Duras book, but not even. My generation was definitely brainwashed by the male gaze. I hope it’s changing a bit, but I am really not sure it is. And I don’t even talk about movies…

I wanted to add a list of the “feminaries” I read while writing This Woman’s Work because they really influenced my thoughts and art. I would not be writing what I write without those books. Art is not only personal; it’s a collective intelligence. The list is also a guide for readers, so that they can know good “feminaries.” There is a turning point when you start craving this kind of book. I worked at the Drawn & Quarterly bookstore in Montreal for four years, and my coworkers were all very smart and compulsive readers, they were mostly women and they were all open to queer theory. That probably accelerated my intellectual bloom. I always was a feminist, but for a long time it was all intuitive and I didn’t read the books that allow you to understand how patriarchy exactly works. Feminism was not a word that existed around me when I grew up. It really all came with those readings, and quite late, from Despentes to Federici. The book of Amy Berkowitch, Tender Points, has a particular place in my heart and story. I had years of therapy behind me, but it was only in reading this book that I allowed myself to consider my history of trauma, a history deeply connected to the story of all women.

In This Woman’s Work, you write, “This book, the one in your hands, was supposed to be about Tove Jansson.” How did the book as you initially imagined it change?

I first wanted to make a non fiction book about Tove Jansson, because I loved the Moomins (the characters of the stories she became famous for) and I felt she was a good subject, that people would love to read about her. So I went to Finland, where Tove is from, to do research about her life. Then I changed my mind, and tried to make a fiction about her, where an anthropologist would investigate on the existence of Moomins. Some pages from this fiction project remained in the final book, when I say I search for Moomins in the forest and that I found a campfire by the water made by Snufkin.

If I was a full time artist at the time, maybe one of these projects would have become a book. But it took me four years to write This Woman’s Work, and at some point I realized why I was so fascinated by Tove Jansson. I was desperately lacking feminine role models that related to me. She was the first woman in comics history whose work and life I loved. When I read her biographies, I fell in love with her character and her life choices. Her connection to wilderness, the fact she had a range of different artistic practices (painting, writing novels, drawing comics)… I wanted to be like her! It was the first time it happened for me, wanting to be like another woman. Before, I had only identified with men.

I found a Christian Rosset quote (a French comics critic): “You have to fail at making the book you had in mind, so that you can end up with a good book that neither the author or the reader was expecting.” So I failed at making my book on Tove Jansson, which anyway would have been too straightforward, almost too commercial for me. It became something better, between a political essay, a personal journal and poetry. Eventually, it’s a book that says: “here is how I became a feminist, and here is why this is the best thing that ever happened to me.”

You go to Greece but say “It’s only after I’ve left the place that the landscape comes alive for me.” What are your methods for conjuring a place to illustrate it when you are no longer there?

The part in Greece in the book is maybe the only one where I included drawings I made in situ, in sketchbooks. Usually, I use a lot pictures (taken quickly as references) to illustrate the places I visited. To sit and draw a landscape is really hard for me! A person, I can… But a landscape is hard. Something very magic for me happened during that trip I made to Greece, I was travelling just for myself. I tried to capture it in the book. I recently realized my work was not at all about capturing the present, at least not the external elements of the present. I write and draw to understand myself and analyze things, to put myself in a narration. I use a lot of introspection and dreams, try to let the subconscious come into the drawings so I can discover things about myself.

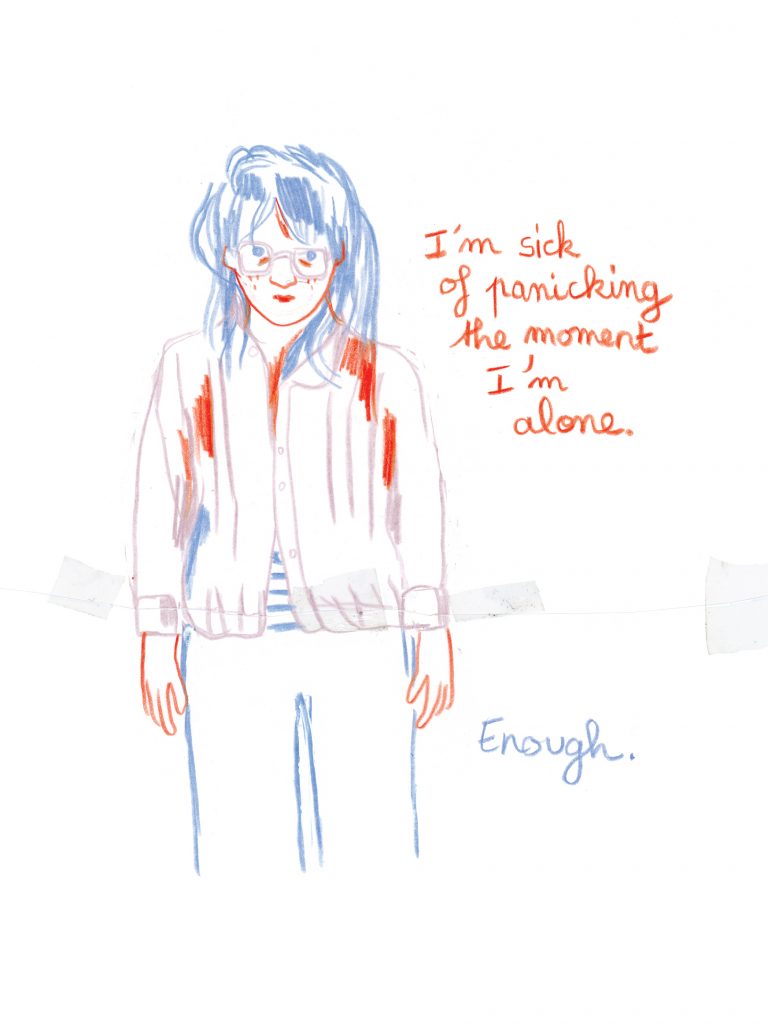

This is something I recently felt the desire to change. For the past years, it’s like I lived considering my life had nothing worth recording in it, nothing precious to keep the memory of… It’s connected to a post-traumatic survival state, I think. Now, I’ve started to re-use my old analog camera, I want to keep track again of my friends, of the moments of happiness, of the places I like… I don’t care about the quality of the pictures; it’s just about testimonies that I really exist, besides traumatic experiences, mental fog, and having an unusual life (no kids, for instance). Life is totally imperfect and most of the time full of pain, anxiety and insecurity, but still, I do have friends, I do have an external life worth being acknowledged and thankful for.

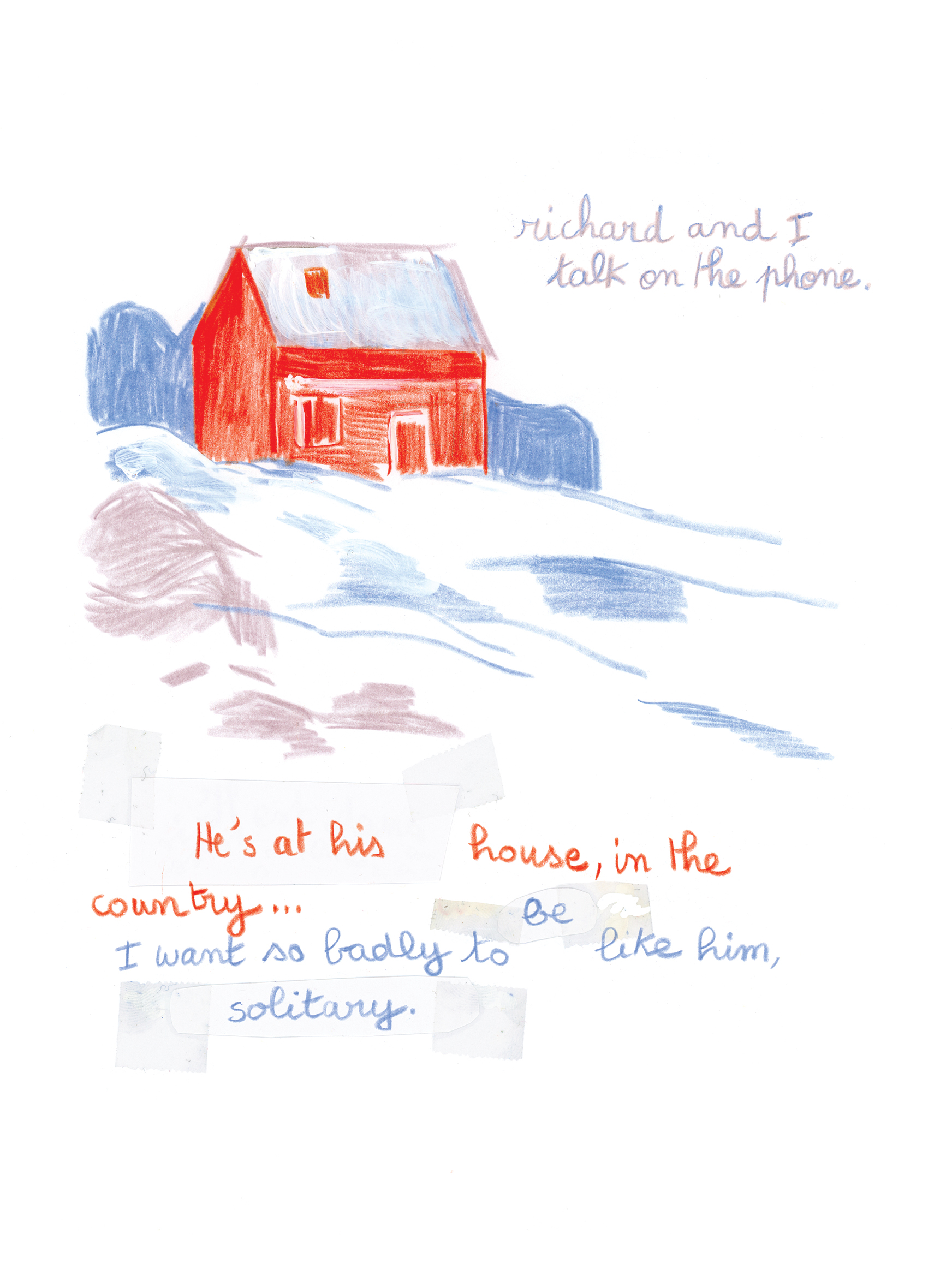

You write that Tove Jansson says there’s no true freedom if we can’t be alone with ourselves, and there’s tension throughout This Woman’s Work having to do with the desire to be alone versus the fear of being alone. What are some of the ways you’ve found to make it easier to be alone? Do you continue to find being alone important to your own life and process?

When I am outside in the countryside or wilderness, I never feel alone. How can one feel lonely when there are all of these bugs, animals, trees, grass, rivers, stars around? I am serious. They do talk to me, and they leave me alone at the same time, which is perfect. It’s really more complicated to be alone in the city… For a long time, when I was with people, especially with lovers but really with anyone, I would adapt everything I’d do and think to their presence. I couldn’t find a mental space to think about my art, it would disappear from my desires and preoccupations, and I became a logistic or emotional worker, trying to make the relationship work, and ruminating on my angriness and worries about it not working.

There is a line about this in the book, “Then they fall asleep thinking about their poems,” which is very dear to me. It never happened to me when I had a male partner, to be able to fall asleep or to wake up thinking of my art… This is why loneliness was so important to me, and still is. But now my idea is to be able to find love relationships and friendships where I still can have access to this secret personal place. Being with others, but still being with myself. Actually, This Woman’s Work ends with the story of a utopian community of women who work together. Not with solitude.

While reflecting on personal trauma, you write, “it’s reading that saves me (like it did when I was little).” What was the reading that was saving you when you were little?

I was probably not reading the best books as a kid. I think it was more about the idea of escaping my reality. Reading was the only time when I was truly happy, or at least not struggling with unhappiness. I was a very sad child. I really felt I didn’t belong where I was, so I could just take a book and read everywhere all the time. I didn’t even want to stop while eating.

Also, my family was not at all into art and culture, and not so much into progressive ideas, so I learned everything that interested me in books. But I have to thank them for the fact they always pushed me into reading, they would buy me books, they brought me to where I am. I recognized this dynamic in Annie Ernaux’s stories, her parents worked hard so she could have access to another class. I think my family hoped for economic success for me, not artistic success, so for a long time I felt guilty using their economic effort to achieve another kind of recognition. You can’t be an artist from nowhere, it’s a myth to think it comes all just from talent. And this is one of the reasons why there are fewer women becoming famous artists.

You say you have a constant desire to learn how to make things more tangible than a text or a drawing. What are you learning to make or making now?

I learned how to make ceramics and I am proud and happy to imagine some people drink their coffee in cups I’ve made on a daily basis. But it’s absolutely not profitable, I can’t sell my pieces at a price that would match the long hours I spend on them, and can’t get any funding for it as it’s not my main medium. I’m not learning many concrete things anymore. I’m learning eau-forte etching, which is close to drawing… Making books is the most concrete work I am capable of. All my energy goes into reading, writing, drawing. I have to, if I want to keep on making a living with art — and it’s really not a big living.

I feel a kind of existential crisis writing this, haha. I wish I could build my house, make a garden, sew my own clothes… But I am not this kind of person, I have to accept it. I wouldn’t have the energy to do all this and write books and make money. I felt worn out by trauma the last years. I like when Hannah Gadsby says: “I identify as tired.” I learned more bird names last year, I keep on going to classes at Université Populaire in Montreal, but it’s always intellectual learning… I feel disconnected from my body most of the time, there is something about dealing with trauma in this way of living.

What are the next text or drawing-based projects you are working on?

I did a public poetry residency in Montreal last year, in an art center called DARE-DARE. I wrote sentences which were written on a light board in front of the art center. Each of the sentences were inspired by anonymous discussions I had with people about rape culture, sexual trauma and gendered violence. The result is a long poem which sounds like a collective voice about a desire to heal collectively. It is not only political, but deeply political. Now, I am illustrating the sentences with eau forte etching, to make a book out of it. I choose etching because it’s a really slow technique, and the whole project was about degrowth (décroissance). Personal degrowth, sexual degrowth. Getting rid of the liberal pressure to succeed… I still have to find a subject for starting a new graphic novel, I am quite slow. I worked a lot on the idea of a book about healing sexual trauma, and realizing it is a collective responsibility to address sexual violence. But I suddenly felt I was not able to think anymore about rape. I do need joy right now. Finding joy became my main goal in art.