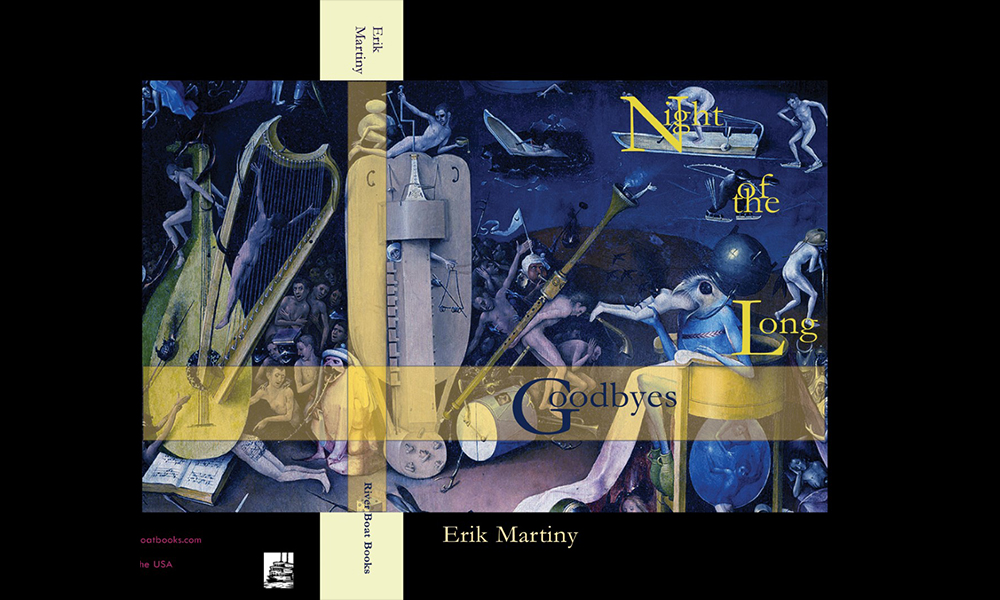

It has been argued that the ongoing global pandemic was caused at least tangentially by climate change. French-Irish-Swedish author Erik Martiny’s latest cli-fi novel Night of the Long Goodbyes is an eerily prescient take on the nature of this dystopia of our making. Like the BBC TV show Years and Years, Martiny’s novel pushes the apocalyptic consequences of our actions further into the future while rendering them more extreme, casting the difficult world we passively accept and enable in greater relief.

In Martiny’s world of the 2040s, the air is so toxic that every human is afflicted with some form of respiratory disease. People carry inhalers around with them wherever they go. Into this fraught setting comes the Blue, an undefinable substance that resembles blue snow. Theories abound concerning the origin of the Blue: it is variously interpreted as an alien species, an extraterrestrial art form, manna from heaven, divine punishment, etc. The novel’s hero, a British everyman named Kvist Kerrigan, embarks on Gulliver-like travels through the land of the Blue, eventually encountering one Bora Johnson, the Lord Mayor of Brexitshire.

Martiny and I communicated over email during the heat of the coronavirus pandemic and discussed how his novel mirrors our unprecedented times.

¤

LELAND CHEUK: Your novel seems to draw a dotted line from recent political developments to the futuristic world in your book — a world where bigotry is more or less accepted, as are climate change catastrophes. Would you say that the novel is a cautionary tale? Do you consider this a political novel?

ERIK MARTINY: Night of the Long Goodbyes became more and more politicized in the final drafts. Although it was initially focused only on the paranormal phenomenon known as the Blue, it morphed into a predominantly political dream narrative. The novel is partly inspired by what could happen if (and probably when) the icecaps thaw and displace between 200 million and one billion climate refugees. It focuses on the outcome of xenophobia 20 years after Brexit. Bent on deporting the descendants of every known immigrant since the nineteenth century in a bid to capture “essential Englishness,” a coalition of gene parties emerges in Britain. Each party harkens back to a historical period when they claim the gene pool was purer. These toxic nostalgia parties have the names of rock bands: Sexy Saxons, Brexit Reloaded, Britannia Romana, Tea and Crumpets, a populist strategy known as Woodstocking.

The novel is ultimately an allegory of our passivity in the face of climate change. Although youth activism is stronger than it has been since the Vietnam War, many people are still extremely passive and resigned. I see this in my classes and have gone as far as to assign eco-gestures as homework since talking about the potentially disastrous future has no visible effect.

What’s an example of an eco-gesture? Has it helped students see that they can do more?

I gave my students quite a few examples of eco-gestures that are easy to perform, like cutting meat consumption, buying charcoal sticks to purify your tap water and carrying it around in a reusable glass bottle instead of buying plastic bottled water (which pollutes both you and the planet). I let them choose their own eco-gestures and asked them to tell me about what they had chosen the next time I had them in class. They all seemed happy to have been able to do something. I checked a few weeks later to see if they were still performing their eco-gestures and they were. These things clearly need to be taught in school.

Why do you think people are so passive and resigned, and has the recent large-scale global protests related to the George Lloyd killing surprised you?

I think most of us are either passive, indolent or resigned about climate change and the environment. It’s partly due to education (we only do our homework because someone tells us to do it), but it’s probably also part of human nature. We are designed to adapt to circumstances and this very adaptability makes us resigned and passive when we should really be actively rejecting any form of pollution. We’re used to breathing polluted air. We were born with that norm so it seems acceptable to us.

I also think we’re resigned because we feel the situation is out of our hands. We feel that no matter what we do on an individual level the pollution and despoliation is going to happen anyway.

It’s our failure to think collectively and respond quickly and radically that will probably undo us, or at least permanently tarnish our already damaged paradise. I think a lot will be done, but only when the signs of danger are dramatically visible. We’re heading in the right direction, but at the speed of a lemur.

I was surprised that the George Floyd murder became a global phenomenon. It does show that young people can be reactive, but I predict it will, I’m afraid, fizzle out quite quickly, at least outside America. Even in America, I doubt it will make much of a difference under the present conservative regime, but any form of protest is important. It’s paramount to stand up to abusive authority on a regular basis. It means those who have power will be a little warier of abusing it in the future.

The concept of the Blue is super cool. What inspired that?

Thanks, I’m glad you like it. The idea came to me over two decades ago so I’m not certain where it came from exactly, but a combination of snow and Yves Klein’s blue paintings were probably the sources. Several of my novels are inspired by art. I also do a little art criticism on the side for Aesthetica Magazine and The London Magazine.

Talk about Lord Mayor Bora Johnson. The name obviously refers to the current British prime minister. In the book, Bora is this organism, a gender-fluid, species-fluid creature. What were you aiming at in Bora’s creation?

The original version of the Lord Mayor wasn’t actually aimed at satirizing Boris Johnson in particular, but in the last drafts of the book I couldn’t help including current events. They just seemed to leak out onto the page. I like the idea that a work of literature mirrors the time in which it was written.

The hermaphroditic, metamorphic Bora Johnson is partly a satire of Brexiteers, but in the dream-like logic of the novel they are far more than just that. You could say that they develop into the opposite of Brexitism since they end up regretting the loss of ethnic diversity and the fact that all LGBTQ people have been sent to concentration camps in the Hebrides. As polymorphous hermaphrodites, they are themselves a kind of gothic expression of the return of the repressed.

You predict in the novel that everyone has some sort of respiratory disease, which some climate scientists have as well. And now we’ve got a coronavirus pandemic with a respiratory disease. In what ways has the current situation surprised you in comparison with the speculative world of your book?

I didn’t intend Night of the Long Goodbyes to be predictive although it was pretty safe to predict the outcome of Brexit so I took that risk. The idea that most, if not all people will end up with respiratory problems seems like an obvious prediction if we continue on our current self-destructive path. Hopefully we’ll wean ourselves off fossil fuels before that happens, but I’m pretty pessimistic about the political will to do that before it’s too late. Like the characters in my novel, most of us are too apathetic to change anything. That’s the effect the Blue has: it induces feelings of apathy and sleep. We’re like the lotus-eaters in the Odyssey, unable to get up and react as we should to save ourselves.

Like everyone else, I was surprised by the sudden eruption of COVID-19, despite the fact that I know that we will be facing more and more pandemics in the future because of the population bomb set to explode in mid-century. The pandemics in my novel are more surreal. A vast number of people lose their ability to experience feelings or even pain. They also experience anhedonia: loss of pleasure sensations. An increasing number of babies are born without ears, eyes, or arms and the scientific community is unable to explain these mutations. They are part of the mystery that is resolved at the very end of the novel.

What is your take on the roots of Brexit? How much do you think Brexit factored in the UK’s relatively poor response to the coronavirus (fourth highest number of cases, second highest in deaths and mortality rate, as of the time of this talk)?

The roots of Brexit are complex and I’m wary of being reductive, but at heart I’m very much against the whole idea of it. It ultimately offers an isolationist, Little Englandist, outdated view of nationhood.

Like most speculative novels, Night of the Long Goodbyes is more cautionary than predictive. My guess is that there will be a small recession (that will probably be worsened by the virus lockdown) and that business will pick up after a couple of years, but as usual the destitute will be affected more than most. Compared to climate change, Brexit is a ripple on the surface of the pond.

It’s clear that the obsession with Brexit and reshuffling the cabinet made Britain slow to react adequately by resorting to contact tracing, social distancing measures and widespread testing. But this sluggish response was also fueled by what underlies Brexit: Little Englandist patriotic preoccupations and delusions of grandeur. The idea that Britain shouldn’t bow down before the foreign invasion of COVID-19 germs is I think linked to the patriotic idea that Britain never succumbed to the Germans.

What were some of your literary influences for this particular work?

The most obvious influences in Night of the Long Goodbyes are Angela Carter, J. G. Ballard, Franz Kafka, Samuel Beckett, Paul Auster, J. M. Coetzee, but I could name another dozen. My novels are crisscrossed with intertextual crossroads.

What are you working on now?

I’m currently finishing up an experimental detective novel that crosses traditional storytelling with metafictional discourse on the construction of detective fiction. It’s part of my project to write at least one novel in each novelistic genre. I must say I found experimenting with speculative fiction far more liberating. Detective fiction is a much more fixed novelistic form but after a lot of frustration and cogitation, I managed to find a few ways to subvert those rules to establish as much freedom as I could within the constraining parameters of the genre.

I’ve more or less finished two shorter cli-fi novels written in French too. Both are set in the near future and explore environmental issues in an occasionally surreal way. They also process the experience of losing my father to cancer.

I’ve also started a further two books, one in French, one in English: a historical fiction set in the 1930s in a German castle and a more personal historical novel about my grandparents during World War II. It’s set in southern France during the near-famine that occurred there in the early 1940s.