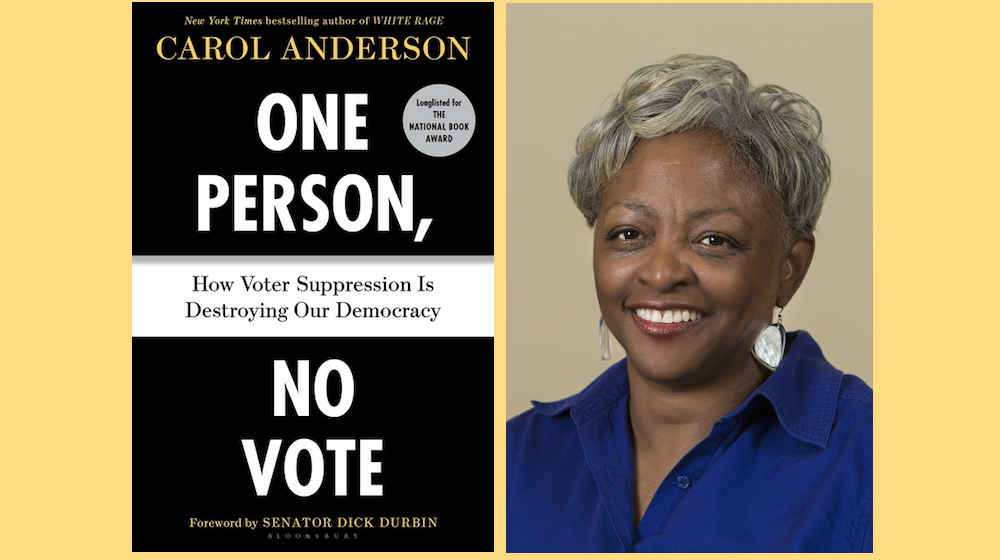

Which perennial patterns of vote suppression, particularly for voters of color, did America’s (and Russia’s) handling of the 2016 presidential election most dramatically magnify? Which most promising developments from the most recent Senate election (Doug Jones’s victory in Alabama’s 2017 campaign) ought we to expand upon in the 2018 midterms and beyond? When I want to ask such questions, I pose them to Carol Anderson. This present conversation (transcribed by Christopher Raguz) focuses on Anderson’s book One Person, No Vote: How Voter Suppression Is Destroying Our Democracy. Anderson is the Charles Howard Candler Professor and Chair of African American Studies at Emory University. She is also the author of White Rage (winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award), Bourgeois Radicals, and Eyes off the Prize. Anderson’s research focuses on public policy, particularly the ways that domestic and international policies intersect through questions of race, justice, and equality in the United States. She has served on working groups dealing with race, minority rights, and criminal justice at Stanford’s Center for Applied Science and Behavioral Studies, the Aspen Institute, and the United Nations.

¤

ANDY FITCH: Could we start with the concept of “registered voters”? Why do eligible voters (presumably all citizens of a certain age, excluding those whose voting rights the state has taken away for some specific reason) need to “register” in the first place? We typically don’t speak of “registered” and “unregistered” Americans, or of “registering” for Bill of Rights protections. And I get that we need to determine a voter’s current address and corresponding district, but that already seems a slightly separate question. Or I get why confirming a voter’s identity prior to a time-limited polling session helps, but our current approach seems pretty 19th-century both in terms of how we verify identity, and in how we parcel out polling sessions. So before we even start outlining deeply flawed aspects of America’s electoral process (before we consider which of our own voting laws get enforced or undermined, by whom, with what intentions, producing what outcomes), which states, which countries have done the most to diminish any difference between the categories of “citizen” and of “voter,” through which methods of automatic registration, biometric identification, mail-in voting, early voting, election-day holidays, etcetera?

CAROL ANDERSON: That’s a great place to start. A nation like Australia, which basically has mandatory voting, gets over 90% voter turnout. You can juxtapose that to the US, where if we get 60% voter turnout, we do this dance of joy. And our midterm turnout rates can get pretty abysmal — sometimes in the 20% range. But one key element that distinguishes the way the US does elections is how we just cannot get away from the issue of race. Race has been determinant in this nation. And a lot of the efforts to constrict ballot-box access still come down to race — more specifically, to not being white (and even more specifically, to being black). A few days ago, for instance, we had all of these celebrations and commemorations about the 19th amendment’s passage, providing that women now can vote. And I celebrate the 19th amendment. But still scholars had to stand up and say: “You realize this didn’t include black women?” And the public is like: “What? Really?” When you begin to think about it, you realize that not until 1965 (so within living memory) did African American women have full (almost) access to the ballot box, which says something striking, something fundamental about American democracy. This issue of registration tells us a lot about containing and controlling who has ballot-box access, and we’ve seen that over and over and over.

In terms of how race shapes our electoral process, from Dick Durbin’s intro (which mentions the Senate Democratic Caucus inviting you to speak, following White Rage’s publication) onwards, the question of who you see this book speaking to, and what you see as its primary purposes, stood out to me. I could see, for example, a broad range of readers considering this book a catalyzing wake-up call on a foundational concern for fulfilling the promise of American democracy. I could see some more specialized readers, already well-schooled in the broader voter-suppression tactics that One Person, No Vote tracks, who might most appreciate your effort to establish an evidentiary baseline for concrete action, and who now want specifics on what strategic forms this action could take. So what conversations do you most want to see happening within these (loosely differentiated) groups, between these groups, between these groups and a broader electorate still considering racialized voter suppression somebody else’s problem to deal with?

I see the book having multiple audiences. Let me first give you a sense of One Person, No Vote’s genesis. As I traveled across the nation giving talks on White Rage, I would discuss one of that book’s last chapters, “How to Unelect a Black President.” This chapter talks about voter-suppression efforts that emerged out from Obama’s election, targeting the multi-racial, multi-class coalition that put him in the White House. And when I gave these talks, someone often would raise his or her hand and say: “I don’t understand. How hard is it to get an ID to vote? Why would you call this voter suppression?” So I would take a step back and talk about how normative this has become. It looks so reasonable. We absorb this image of a democracy in peril because of all these people supposedly committing voter fraud and stealing elections. The rational response, then, is for intelligent people to say “We need this voter-ID requirement, because you already need an ID card to do things like check out a library book.”

But when you explain the genesis of these policies, and their actual consequences, then you see a shudder come through these audiences. So I had my light-bulb moment, where I realized: Whoa, we have a story to tell here. Because I firmly believe that most Americans are good people, and will mobilize when they know the truth. The one thing everybody can agree on is democracy. And when we can show the effects that these racist lies have had on our democracy — nobody wants to live in a nation like that. Or most people at least don’t want to live in a nation like that.

And so I do see this book in some ways as a clarion call, as being able to lay out, to document (the way scholars do) what has happened to get us here, and why that has happened, and what consequences we now face thanks to all of that voter suppression, and how you cannot contain those consequences. Too many Americans have responded to this situation with that Jim Crow way of thinking: Well, this affects black people, but I can still go off to my nice white suburb, and to work, and to take care of my kids, without it really affecting me. The Civil Rights Movement made it clear, though, how Jim Crow was absolutely corrosive, how it affected everybody. And we have to realize that voter suppression does the same thing.

So I see this book’s audience as multi-fold. I see policy-makers, absolutely. One Person, No Vote lays out there, for instance, how federal legislation gets hijacked, tainted, twisted, and corrupted — how it has allowed these poison pills to be inserted into the workings of our democracy. The 2002 Help America Vote Act included voter ID, placing the lie of voter fraud somehow on par with the reality of massive voter suppression that happened in the 2000 election. The 1993 National Voter Registration Act included this part about cleaning up the voter rolls, which again sounds fine, but which has been used to target minority populations, to remove them from the voter rolls, to skew elections, and to skew who our elected leaders are, to skew policies emanating from so-called representative bodies. Policy-makers need to be much more astute (and of course some of them already are, in good ways and bad) about the implications of laws they sign off on, of what they propose, and what consequences that brings. So yes, policy-makers are one audience.

For another audience, of regular folk: they sometimes look stunned when you describe the closing of polling stations, the lack of resources allocated in minority precincts, the polling machines that don’t work in certain neighborhoods, the polling stations with only one or two machines that do work. You have these lines stretching from here to eternity. Even a colleague of mine, a white woman, said: “Wow, in my precinct I hop right in before work to vote, and it only takes a few minutes.” So I want this book to reach that audience as well. And I do think it’s crucial for us to have that evidentiary baseline — not only because I’m a scholar and I don’t know how else to do it [Laughter], but because that baseline can provide evidence-presenting talking points to rebut the foolishness and the lies out there. For example, when someone says “We’ve got rampant voter fraud,” you can say: “Well, you know Greg Abbott only could point to two cases in Texas.” It’s like: “Two? In all of Texas?” Just think about the millions of dollars wasted on that lie about Texas voter fraud.

And then one other audience here is our civil society, people in the courts, in grass-roots organizations — to give them a book that isn’t 500-pages long, that’s accessible, engaging, and documented. Sometimes when you fight those battles it’s so important to get that context, to know about all these multiple fronts being fought at the same time. This book tries to give those amazing individuals more information, some additional tools, to do what I call the heavy lifting of democracy. I don’t know what we would do without our civil society.

Getting back then to your own training as a historian, we no doubt could call this book quite timely, and also long overdue. One Person, No Vote opens with the claim that while conventional media wisdom suggests Hillary Clinton’s personal failure to energize voters of color cost her the 2016 election, in fact, Republican voter-suppression tactics systematically blocked more than enough would-be voters to deliver the presidency to Donald Trump. And then One Person, No Vote closes by pointing to how Russia’s unprecedented assault on our 2016 election reinvented racialized voter suppression, discredited anew our electoral process, further undermined confidence in basic democratic fairness. In between those bookends, One Person, No Vote ties together a much more sustained and systemic history of often state-sanctioned assaults on African Americans’ voting rights. So how do you see that temporal vector of perennial minority-voter suppression and of post-2016 electoral panic coming together? What new prospects do you see right now for addressing fundamental political inequalities we sometimes claim to have resolved half a century ago? What new difficulties do you find today in providing a constructive critique of our current electoral practices that does not contribute to the growing distrust of and disillusionment with basic democratic functioning (not just in the US, not just based on our own problematic racialized legacies, but worldwide at present)? How to make your urgent case here without further marginalizing the most marginalized Americans, by making democratic civic empowerment seem simply unattainable, not even worth trying for?

Great question. That’s why the last chapter focuses on Alabama, even as so many people act like Trump presents this radical break from the American narrative — as if he just sprang like Athena out of Zeus’s head, but not nearly as smart [Laughter].

But to take a step back, Emory had sponsored this faculty initiative called the Op-Ed Project, to train established researchers from a wide range of fields in how to write for a broader audience. I’m used to writing long, thoroughly documented books. So how do you turn that into a 700-word op-ed? At first I couldn’t envision how a historian could jump into present-day discussions and provide the right context, but the Op-Ed Project helped me hone that voice. This really came through in the Washington Post op-ed on Ferguson, where I figured out how to put Ferguson into historical context, from Reconstruction through Barack Obama’s election. That article resonated. It was the Washington Post’s most shared piece for 2014. Writing it showed me that what historians bring to the table is not only “This is not new,” but: “Let me tell you how we got here. Let me tell you about the underlying tectonic plates moving this thing. Because if it always looks new, then we’re always reinventing the wheel, and falling into the same traps. But if we understand this story’s historical arc, then we can have a very different kind of conversation.”

So you’re right. I started reading these election post-mortems, and getting furious, thinking: How did you miss this? I mean, Ari Berman saw this. Thank god for Ari Berman. He seemed as frustrated as I was at these stories just dripping with contempt for Hillary, but not showing that same contempt for our flawed system. In Wisconsin, they had 60,000 fewer voters in 2016 than 2012, with 68% of that reduction happening in Milwaukee, where 70% of the state’s black population lives. Trump then wins that state by a little over 20,000 votes, but that is attributed to African Americans being repulsed by or indifferent to Hillary. Yet, we’re talking a 68% drop in the voter-turnout rate. 68%! Many reporters, however, went to Milwaukee and made a structural problem personal. This was the first election without Voting Rights Act protections since 1965, so are we just going to continue holding elections and acting like the Voting Rights Act doesn’t matter? Are we just going to agree with John Roberts when he says that today’s racism is nothing compared to the Jim Crow era? Or that we’ve got black and Latino politicians, so we don’t need the Voting Rights Act, which unduly targets the South and just isn’t fair? If that becomes our reigning narrative, then we’ll just have more vote-suppression techniques applied with nearly “surgical precision” against African Americans.

I do want to make clear that the Voting Rights Act’s removal isn’t just some insignificant detail. This is deep, profound, and real. That’s why I start with Hillary, and why I end with where we are right now. That’s why I also love Reverend Barber’s quote: “Voter suppression hacked our democracy long before any Russian agents meddled in America’s elections.” The Russians attacked where we already had been pounding on our own population. We drew a big circle with a bullseye around it and wrote “Hit here.” We have to own that. And owning that means in part going back to the 1890 Mississippi Plan, the first disenfranchisement plans during the rise of Jim Crow. Mississippi said: “Look, the 15th amendment says we cannot discriminate on the basis of race. How do we get around that 15th amendment? I know! Let’s target the socially imposed characteristics of African Americans, and make those characteristics the litmus test for the right to vote. That way nobody can say we went directly after black people.” Then Carter Glass, the Virginia politician, looks at this Mississippi Plan and does the dance of joy, and says: “Oh yes, this is how we eliminate black folks from the ballot box. We’ll get rid of 80% of them.” Except Virginia’s plan works so well that by the 1940s, with the US fighting Nazis, only 3% of eligible African Americans are registered to vote in the South.

Returning to that op-ed training you received, One Person, No Vote offers in part a striking follow-up to how Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow drew out deeply disturbing and yet undeniable parallels in the institutional functioning and lived personal consequences of US slavery, US Jim Crow regimes, and our present criminal-justice system. The New Jim Crow (operating in some ways more by analogy than by documenting the type of dramatic scenes we associate, say, with mid-20th-century Civil Rights struggles) sought to bring to visibility an (almost by definition) often concealed institutional injustice. Here I think of you likewise assembling this compendium of shame: tying together insidious, interlocking techniques of impeded and rescinded voter registration, curtailment of voter access to the polls, under-resourced and antiquated electoral mechanisms. I think of how the lived experience of a voter getting, in your own terms, “harassed, obstructed, frustrated, purged,” again typically takes place out of public view. And here especially I appreciate your apt description of those Jim Crow-era poll tests as both “mundane and pernicious.” I sense that your emphasis on the racial animus so often driving voter suppression seeks to dispel conventional assessments that voter suppression is a “boring,” “bureaucratic” topic for most contemporary Americans — here by letting those more pernicious or malicious sides of such seemingly mundane tactics more dramatically reveal themselves. Do you think we still need that image of moral clarity, under the sign of explicit racial animus, in order to call the bluff on Republican claims of “administrative efficiency” (an “efficiency” which somehow just always seems to lead to lots of black citizens losing their voting rights)? And again, how then to pivot from that moral call-out to prompting the concrete policy changes we now need?

I want to make that whole system much more visible. I mean, Jim Crow was pervasively nasty, but so much of it took place out of public sight. The states went out of their way to make that evil less visible, because something that makes the United States the United States is that we remain an aspirational nation. “We hold these truths”…of course that didn’t happen! But we still hold on to that aspiration. We still have “with liberty and justice for all” as an aspiration. And the Civil Rights Movement appealed directly to that aspiration, saying: “This is who you say you are. But this is what you’re doing.” They documented that dramatic difference. They showed us the Bloody Sunday march across Selma’s Edmund Pettus Bridge, with the Alabama State Troopers and Sheriff Jim Clark and his deputies trampling, tear-gassing, beating protestors into a bloody mess. During that particular moment, ABC couldn’t help cutting into its own Movie of the Week, Judgment at Nuremberg, to show the public those Bloody Sunday events. That shocked their audience, showing what was happening right here in the name of democracy.

And like you said, nothing in my book stands out as equally dramatic to what happened on the Edmund Pettus Bridge, but still I want to make visible the pain, the turmoil, the degradation that these systems put American citizens through — most often for no other reason than their race. Though One Person, No Vote also has this broader swath dealing with issues of poverty, with keeping poor folks away from the polls. So any number of American citizens will not have a voice in the policy-making ranks, because of what we’ve done. When we start getting glassy-eyed over policy, we tend to ignore how it sets the parameters for the way we live our lives. I do want to make that visible.

Here we can go back to Alabama, two years before the 2013 Shelby County v. Holder decision, when Alabama still had preclearance requirements — needing Justice Department approval to change its voting laws. In 2011, Alabama drew up this absolutely draconian voter-ID law. Republicans are quoted asking: “How can we suppress the black-voter turnout?” So I’m thinking that this law just might have some discriminatory intent [Laughter]. Alabama knows it can’t get this law through the DOJ, so they sit on it until Shelby.

The law that then emerges limits the types of IDs someone can use to vote. It excludes government-housing IDs, which are certainly a form of government photo ID. How does it get more government-issued than public housing? But 71% of Alabamians in public housing are black. If you ban the kinds of IDs that black people have, then you can wither away that voting bloc. Then Alabama starts shutting down Department of Motor Vehicles offices in the Black Belt counties. People start having to go out of county, sometimes 50 miles, to get a driver’s license. But if you don’t already drive, how do you go 50 miles? So again, civil society weighs in, and then the Obama administration’s Department of Transportation says shutting down DMVs restricts ballot access. So Alabama opens these offices for one or two days a month.

You can see how this all (simply requiring an ID to vote) looks innocuous on the surface, but then also how the laws have this disparate impact on certain groups. You begin to understand that these laws don’t really intend to mitigate voter fraud, which nobody can find anyway. So what happens when Matthew Dunlap, Maine’s Secretary of State, forces Trump’s Election Integrity Commission to open its records on voter fraud? It once again becomes very clear that this commission only has a blank page to show for itself. We see again this big farce designed basically to entrench Republicans in power — although our nation’s demographics are not aligned to the values and policies of that party. The GOP saw this demographic apocalypse coming. The party had options. But instead of reforming, it chose, instead, to suppress as many voters as possible. How they chose door number three, while claiming to protect democracy, I don’t know.

Here though, for me, longstanding conversations about voter-ID laws also do start to show some potential limits to the efficacy of emphasizing racial animus in pursuit of moral clarity. And here I also would start from what seems like the objective fact that Republican claims of rampant voter fraud have been shameful lies for a long time now. I’d point out all the catch-22’s of how you might need a driver’s license to get a copy of your birth certificate, and might need a birth certificate to get a driver’s license. But with all of that said, I still see two separate arguments at play in voter-ID debates, and a polarized conversation in which nobody ends up advocating a desirable outcome. I see many Americans more or less indifferent to ridiculous Republican claims of voter fraud, and yet still considering it simple common sense, as you noted, that if I need a photo ID to buy a glass of wine or to walk into a health club, then my fellow citizens can be expected to provide a photo ID to vote. And when voting-rights advocates then appear to accept and even to perpetuate a social system in which large numbers of Americans stay so isolated that they can’t get the proper ID, I don’t see that as a successfully unifying message. Or when you describe voter-ID laws as “a solution in search of a problem,” I can agree with this sentiment, but I worry about the apparent implication that we shouldn’t always be modernizing our electoral system long before problems arise. For all these reasons, I wonder why Democrats haven’t already proactively triangulated this debate by saying: “OK, we as a society will use voter IDs, and will use them not to suppress our most vulnerable citizens, but to empower every single citizen. We will not rest as a country until we get these IDs into the hands of every eligible voter, and we will exemplify foundational principles of both Democratic liberalism and Republican conservatism by taking basic decision-making powers away from vested interest groups, and restoring these to the people.” Or for a more concrete question here: let’s take the 2006 Indiana law that, as you say, cynically pledges to provide free voter IDs, without providing adequate resources for marginalized citizens to acquire those IDs. What about a voter-ID law that does provide adequate resources? Why can’t we imagine this as possible?

Well kind of like with the Help America Vote Act, I think that cedes terrain to this pernicious lie that voter ID ever was necessary. I for one don’t want to cede that terrain. When Senator Kit Bond put the voter-ID part into the bill, this signaled to people that something had gone awry with our electoral process. When we cede that terrain and promise again to put an ID in everybody’s hands, I worry we’ll get the same results as last time. The Help America Vote Act included a broad array of IDs, right? You could use a utility bill, a bank statement. Now that already has racial implications, with 20% or more of African Americans not having a bank account. Or if you live in a multi-generational home, only one person’s name might appear on that utility bill. Minorities live in multi-generational homes more frequently than whites. So I see any voter-ID requirements still having those same kinds of racial implications.

You know, sometimes while writing this book I just had to stop and shake my head. I remember, as an undergrad, having one constitutional-law professor who would just stop in the middle of a court case and go: “God love a duck.” That’s what I feel sometimes: God love a duck. When Justice Stevens, in that Indiana voter-ID case, says something like “There’s no indication whatsoever that anybody at any time has impersonated anyone else to vote in Indiana,” I’m thinking: We’re done here, right? But then he goes on and on about Boss Tweed and New York in 1868? It’s like: “What?” That’s what I mean about how this ground gets tilled, with folks thinking that where there’s smoke there’s fire (to mix a metaphor).

Sure, the only thing that trips me up here is the lingering question: does any effective critique of voter suppression need to show more positively that it can produce an adequate electoral system of its own? To give another example, reading about racialized voter purges infuriates me, so that I really don’t know what to do with myself. And I get that the Interstate Crosscheck System, as presently implemented, might be a total joke. Does it necessarily follow though that any such nationalized voter database is inherently flawed? Does the suggestion that such a nationalized database just can’t work in fact serve to justify state purges — since how else can you keep your records clean? Or even the argument that such a database inevitably will be biased against people of color, who tend more often to have common last names, probably makes some voter-fraud agnostics think: Hmm, maybe it is easy to fake votes after all, especially if you have one of those last names… So again, I take your point that these charges don’t merit any serious intellectual response. Yet they seem to have worked pretty well to persuade a decent number of Americans. So what do we do about that?

I was giving a talk before this book came out, and I actually got that question you’re asking right now. I said: “Think about it. We didn’t have ID laws before this, and the number of fraud cases was infinitesimal. Where there has been voter fraud, it mostly has been elected officials stuffing ballot boxes, or with absentee ballots. It hasn’t involved somebody impersonating someone else to vote. So why create a solution to this problem that we don’t have?

And the bigger reason these voter-fraud arguments have worked so well comes from how they link the cities, the “urban” areas, on this dog-whistle codeword for black people. Then they link that to “stealing elections,” with blacks and criminality again psychologically linked. Jennifer Eberhardt from Stanford confirms this all in a study. If you link black criminality to stealing elections, you have traction there. The American Center for Voting Rights, a right-wing front organization that was instrumental in packaging and selling such lies, has this “most wanted” list of cities with supposedly the most rampant fraud, and each of these cities just happens to have a 32-95% minority population. You don’t see Salt Lake City on this list. You don’t see Bozeman, Montana. Instead, you get Trump in Pennsylvania in 2016 saying “We have to keep an eye on Philadelphia.” That’s a dog-barking whistle if there ever was one.

Your book also clarified more than ever the self-fulfilling prophecies of this white paranoia, which has suppressed voters of color for so long, and so strenuously in recent decades, that any truly democratic “one person one vote” tally of course feels to these suppressers like a flood of supposedly less legitimate votes. But I basically had asked you what would be an adequate government remedy for this current situation. And you gave me a smart rationale for why maybe that question just entangles us further in a fake debate. So more broadly then, in terms of the value of seeking constitutional remedies for claims of legal injury (here the deprivation of voting rights), I could read your book’s documentation of our local and state and federal governments, for centuries, betraying their own stated duties to protect their citizens’ rights, and I could read your book’s disturbing scenes of disenfranchised citizens forced to plead their case to the very officials voted in thanks to racist voter suppression, and think: Legal remedies aren’t going to get us anywhere beyond, at best, some brief respite before the racist historical norm resumes. At the same time, I could read your accounts of heroically resilient pushes for constitutional justice in the face of endless governmental obfuscation, or of the US judiciary (at its best) reaching ever further towards truly addressing even the most subtle efforts at citizen disenfranchisement, and think: We just need to keep pushing even harder, and maybe come up with our own Federalist Society, and maybe never feel that we’ve achieved permanent victory, but at least feel better prepared for persistent struggle. Do you want your reader to take away either of these perspectives (or, perhaps, some ambivalence caught in between) on prospects for legal remedies?

This is a multi-faceted fight. It requires that legal fight. In the case of Alabama: in 1901, when they crafted their Jim Crow constitution (meant to disenfranchise black voters, and to institute “separate but equal”), they included this “moral turpitude” clause saying that if you get convicted for a crime of moral turpitude, you lose your right to vote. Now Alabama failed to define moral turpitude, and you don’t find moral turpitude on the books as a crime. So what does this phrase mean? If you ever try to vote after committing a crime of moral turpitude, you can get hit with some kind of felony. And once you’ve gone to an Alabama prison, you don’t want to go back! If you ever get out, that is. And you certainly don’t want to go back because you tried to vote.

It took civil society (the ACLU, the LDF, the NAACP, the League of Women Voters) suing Alabama, year after year after year, to finally define moral turpitude. The state dug in its heels and fought it, but civil society did not give up. Finally, in 2017, Alabama defines moral turpitude. Think about all the Americans between 1901 and 2017 unfairly losing their right to vote because Alabama wouldn’t define moral turpitude. And if civil society had not weighed in, we still would have that moral-turpitude disenfranchisement in 2018. That’s what makes those legal battles so essential. We can’t give up that realm for a second. That’s what makes the battle over Kavanaugh right now so important — not just because of voting rights, but because of what he’ll do to reproductive rights and to environmental rights. We cannot cede this terrain in a society that likes to think of itself as ruled by laws.

Let me tell you one quick story. One question I asked students in my recent Civil Rights Movement class was: which strategy do you think played the most important role in the Civil Rights struggle, and why? Some students talked about non-violence. Some focused on the religious basis. But one really astute student wrote about this power of the legal struggle, about what the Brown decision did, what the Boynton v. Virginia decision did. All of a sudden the state just pounding and beating up on black folk becomes illegal, and that provides the basis for this long-term fight, and ultimately that exposes this deeply wrong, deeply unequal system willing to take illegal action in order to keep its population down. So we have the moral arguments, of course, but we also need these legal arguments. We need these organizations taking voter suppression to court over and over and over. We don’t always win. And we have Trump and this compromised Senate now packing the courts with unqualified judges and right-wing judges, which means more trouble.

Well it sometimes seems that One Person, No Vote ratchets up the despair throughout (with its frightful depictions of, say, Jeff Sessions’s and Kris Kobach’s quite recent climb to national prominence) just to get us to 2017 Alabama. What worked then and there, both in terms of electoral mobilization and in terms of how voting advocates played the “long game?” What lessons can other voting-rights insurgencies extract from Alabama, and which lessons seem inherently local — with each particular effort to counter voter suppression needing to figure out tactics for itself?

I love that language of “voting-rights insurgency.” That’s certainly how I see this. First, these groups didn’t start in October, with the election coming in December. Alabama had employed every method of voter suppression against its population. It required a limited range of IDs, shut down DMVs, conducted massive voter-roll purges in August 2017, gerrymandered (which you wouldn’t think would matter in a statewide election, but gerrymandering demoralizes the population because you feel like your vote doesn’t count), reinforced this massive felony exclusion due to moral turpitude (with 8% of Alabama’s overall population, and 15% of Alabama’s black population, supposedly disenfranchised because of moral turpitude). Alabama also shut down 66 polling stations. After Shelby, states that had been under Section 4 preclearance shut down 868 polling stations. Again, the literature shows quite clearly that for every tenth of a mile you move polling stations from a black community, voter turnout goes down a certain percentage.

Alabama was bringing it. That’s part of what made this 2017 election so powerful, because civil society rose up in Alabama. The state NAACP (and local branches) fully engaged against voter-suppression tactics. First, they worked hard to clarify what specific tactics they faced. Second, they got the word out about what those tactics might do, and how black folks had the power to move that mountain. Third, the NAACP worked with a range of groups (one single group cannot do this work, which requires full-force effort). So let’s take the moral-turpitude case. Finally, in 2017, Alabama passes a law defining moral turpitude as rape, murder, treason — really big offenses. You don’t see drug use on that list. You don’t see minor drug-dealing. So then voting-rights groups turned to Secretary of State John Merrill and said: “You told all these folks they didn’t have the right to vote. Now tell them that they do have that right, that they have not lost their voting rights.” Merrill said “I don’t think that’s a good use of state resources.” Voting-rights groups basically responded: “Not today Satan, not today.” Alabama’s legal society and Alabama’s ACLU did a two-prong publicity campaign (because a lot of media is generational), through the black radio stations and through social media. They said: “Hey, you might have a felony conviction. You might think you can’t vote. But according to this new law, you actually might be able to vote. Come to our restoration clinic, and we can tell you about that. Welcome back to being a citizen.” They just really laid it out that you can engage again. They worked with the black churches. They held the first restoration clinic at Brown AME in Selma. You had a team of lawyers and volunteers looking over arrest records, informing citizens whether they qualified for moral-turpitude exclusion.

Then another volunteer team helped folks register to vote. A key element was getting mug shots approved as government-issued photo ID. If you think about it, someone who has been in prison for a while no longer has a valid driver’s license, but they do have a mug shot. And then these voting-rights groups also recognized that some folks aren’t going to step foot in a church. They set up caravans traveling all around Alabama, to the poorest neighborhoods, restoring people’s right to vote. That’s civil society. When Alabama claimed that getting citizens registered to vote doesn’t use state resources well, civil society stepped up.

You also had a group called TOPS (The Ordinary People Society) going into jails, because Alabama had on its books that those in jail can vote by absentee ballot. Again, this is another instance of how knowing the law was absolutely essential to this struggle. Now folks who have been in jail of course still might feel hesitant to vote because of this moral-turpitude thing. So really reassuring thousands of Alabamians that they could vote was huge.

And that shows you how some parts of struggles like this have to play out locally. In a culture where knowing your neighbors is first and foremost, this meant knocking on people’s doors and just sitting down and talking with them, listening to them. Over and over voters talked about and heard about healthcare, education, jobs, the criminal-justice system. On the one hand, you had a candidate who believed America had been great when black people were enslaved. On the other, you had a candidate who took Klan members to court for bombing the 16th Street Baptist Church and killing four little girls. Alabamians talking to Alabamians made those differences real.

Voting-rights groups also recognized how voting has a social as well as a personal function. You had the NAACP attending class reunions and passing out voting information. The NAACP looked at those churches central to the black community, and had data showing folks in certain congregations weren’t voting, and said: “What you did in 2016 didn’t work.” The NAACP got this list of people who hadn’t voted in 2016, or who had voted erratically, and started calling them, and then shared that list with Indivisible, so that this organization could call folks.

But again, that’s only part of it. You had VoteRiders, a nonpartisan group who doesn’t want to argue the pros and cons of voter ID — who just says: if people need an ID to vote, then we need to get them that ID. VoteRiders got in there early, around January, because like you mentioned, somebody poor of a certain age probably wasn’t born in a hospital, probably doesn’t have a birth certificate. So pulling together the documentation to get a driver’s license will take more than a couple days, more like months. Again this means knowing the local process and who needs your help most.

And after you’ve done all that, then how do you get people physically to the polls? This is some masterful stuff — reminding me of how, with the 1955 Montgomery Bus Boycott, they set up a private-car system to get folks where they had to go. In 2017 Alabama, these voting-rights organizations coordinated a similar car-service to get people to and from the polls. John Merrill predicted a voter-turnout rate of about 25% for this key midterm election. Statewide they got 40%. In the Black Belt counties, they got 45%. So the most suppressed population actually exceeded statewide averages. The Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights, and BlackPac, sent teams of lawyers into key precincts to document any shenanigans happening at the polls — like turning people away, telling them they’re not registered. Some polling sites only had one working machine. But as long as you get in line before the polls close, you have the right to vote. They can’t stop you. Or when poll workers denied voters’ mug shots, saying “Oh that doesn’t count,” you had groups showing people their rights, showing poll workers the law.

Since you mentioned poll workers, do you see progressives at all starting to absorb the lesson that if they anticipate unfair voting processes, then they should get themselves a seat at the table, by figuring out how to become election officials, and not letting the Katherine Harrises of the world dictate terms for them? And more generally, I hear implicitly in your book a sense that the solution to these shameful circumstances won’t come from sitting around waiting for paranoid white people to get a conscience. So perhaps with the refrain “The white people do what they want anyway…. Because we let them” in mind, what other most galvanizing actions do you see being taken by which political leaders, activist groups, concerned-citizen campaigns, voter-registration initiatives, to encourage voters of color to take their fair share of voting power, rather than calling on Republicans to give them their rights back?

That absolutely is a priority. We need this sense that you can’t give me what’s already mine. I’ll tell you a quick story. I was watching something on PBS about the Works Progress Administration back in the Depression era. A white man was interviewing a formerly enslaved black man. This white man wanted to get across that he wasn’t like all those other white people. You know, he said “I believe the Negro should be given a good education, a right to vote.” That black man looked at him and said: “Stop right there. You’ve got the disease too. You can’t give me what’s already mine. All you can do is try to take it away.” We all already possess this right to vote, so this is about empowering, about knowing what has been done under the ruse of democracy — what actually has undermined democracy and our citizens’ rights. I want this book to get people mobilized, to get us energized, to clarify the playing field. We need to see all these lies behind something that looks as antiseptic as gerrymandering. “We’re just drawing the districts, that’s all!” No that is not all. “We’re just maintaining the voter rolls!” No you’re not. You’re trying to make me, an American citizen, unable to engage.

In terms of gerrymandering, which your book describes as “the worst chicanery,” let’s say Democrats do quite well in state elections in 2018 and 2020, and find themselves much better positioned for redistricting initiatives following the 2020 Census (and here assuming, of course, that the currently completely dysfunctional census preparatory process doesn’t collapse upon itself). How should Democrats then approach this redistricting?

I definitely think we need nonpartisan redistricting commissions. Gerrymandering to benefit the Democrats, like in Maryland, doesn’t do anybody much good. Those nonpartisan districting commissions, I believe, can draw the kinds of fair, one-person-one-vote districts that make our democracy far more vibrant — where your voice gets heard, where elected representatives pursue policy initiatives necessary to make this nation and our local communities function as well as they possible can.

Think about how gerrymandering leads to this almost incomprehensible attempt to dismantle the Affordable Care Act, with Republicans just hell-bent and determined to destroy this law when over 70% of Americans want to keep it in place. The journalists can’t figure this out. How do you have Congress trying to move in one direction when polls show so much of the country wants to move in the other direction? That’s the power of gerrymandering, the power of Citizens United. That’s where you get this horrific tax plan transferring $1.5 trillion dollars in wealth to those who need it least. Again that all happens when you have a Congress beholden to something other than the electorate.

For one additional example of an institutional structure that seems drastically to exacerbate racialized voting disparities, without much overt racial animus needed to reinforce this institution for the last 200 years or so, I think of the electoral college. If you wanted to gerrymander our national map to concentrate (and thus dilute the individual significance of) voters of color, or more broadly to hollow out the voting power of tens of millions of citizens (and discourage many millions more from even voting), our electoral-college allocations seem to achieve those goals quite well. This electoral-college distortion likewise probably contributes to a broader national apathy, first by reinforcing the inaccurate regional assessment of voter suppression as a “Southern problem,” and then by contributing to the sense that voter suppression happens in so-called red states that Democrats will lose anyway. Obviously dissolving the electoral college would by no means prevent any number of other voter-suppression measures, but again, in terms of a proactive call for sensible bipartisan reform to make our electoral process more functional, is this the type of issue on which we might not need to expose racialized animus — with at least some conservatives, invested in democracy as a citizen-driven project, perhaps agreeing with the critique on its analytic merits? Or on what other topics could we make the strongest case to self-identified conservatives that democracy itself needs to change?

Definitely part of the problem has been Paul Weyrich and the American Legislative Exchange Council’s (ALEC’s) framing of democracy — that their power goes up when fewer people vote, and that conservatives don’t believe in any broad-based electorate. Even at this present moment (let alone throughout US history), Republicans like Steve King and Representative Ted Yoho will say “Well, remember when you used to have to own property if you wanted to vote?” Or Ann Coulter has said “I don’t think there’s anything unconstitutional about a literacy test.” Um, yes there is.

But the closing of the franchise has just not been an anti-black conservative project. And that’s why I want to show historically that when the Mississippi Plan, which provides a full array of disfranchising tools, gets implemented, conservative leaders say things like “We need to get rid of the vicious whites too.” Voter suppression might first target black folk, but it doesn’t stop there. You can’t contain this stuff. That’s part of the myth with which we live. During Jim Crow, many people in the North believed that whatever was happening down South, that was just Mississippi. That was just Alabama. No: that’s America, and it affects America.

So today, like you said, when people consider this a red-state thing or a Southern thing, they’ve got to realize that some of our most virulent voter suppressors operate in the Midwest. Look at Wisconsin. Look at Ohio. Ohio purged two million voters. In one of those purges, 25% of all purged voters came out of Cuyahoga County, which includes Cleveland. So this affects us all, and thinking about democracy as conservative or as liberal has just led us down a rabbit hole. Democracy means creating a vibrant nation where we all have a voice in the policies that govern our lives. It’s not Paul Weyrich talking about Republican power going up because people can’t vote. No. America’s power goes up as more and more Americans vote. That’s who we are, and where we need to be.