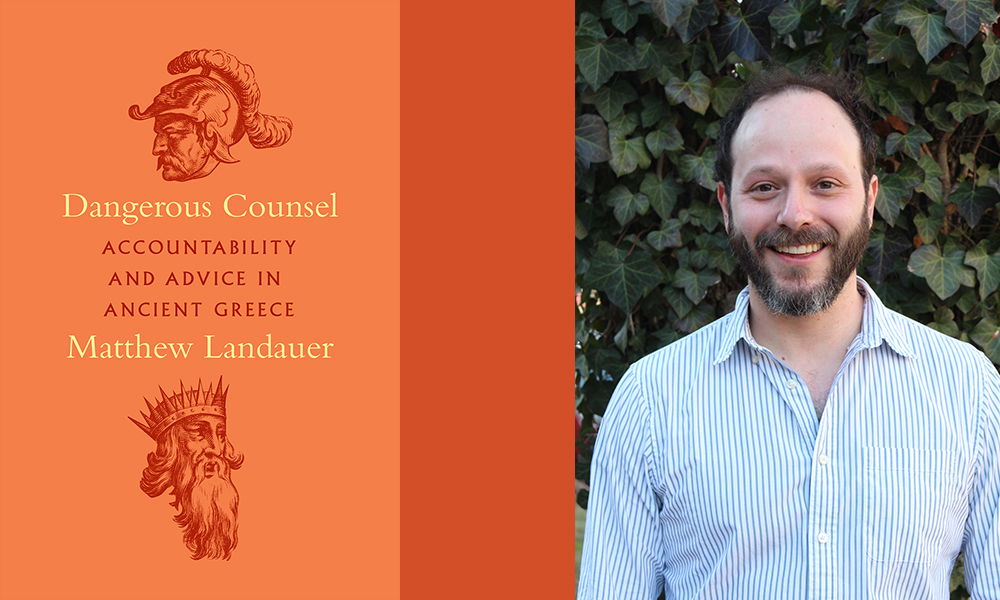

When do tyrannical and democratic decision-makers not differ so much? When should democracies hold their own citizens more accountable? When I want to ask such questions, I pose them to Matthew Landauer. This present conversation focuses on Landauer’s book Dangerous Counsel: Accountability and Advice in Ancient Greece. Landauer is an assistant professor in the Political Science department at the University of Chicago. His research and teaching focus on classical political thought: especially relationships between democracy and other regimes, rhetoric and political counsel, and knowledge and politics. His writing has appeared in journals including Political Theory, History of Political Thought, and Polis. He is currently writing a book on participation in ancient Greek oligarchic and democratic regimes — reading Plato as a theorist of institutions, interested in the conditions for legitimate and effective mass participation in politics.

¤

ANDY FITCH: Could you first sketch the case that some contemporary philosophers and deliberative democrats might make for considering ancient Athens “an idealized system of reciprocal or mutual accountability”? Could you then point to what Dangerous Counsel characterizes as a foundational tension driving Athenian democracy, emerging from the fact that “Ordinary citizens, acting collectively through the assembly and popular courts, were the final decision-makers in Athenian accountability politics — but were themselves unaccountable”? And could you start to outline certain shared structural dynamics of political accountability (regarding concerns of trust, responsibility, advice, manipulation, control) that shape decision-making both in Athens and in contemporaneous autocracies, both in ancient (highly participatory) direct democracy, and in present-day representative democracy’s public rhetoric and elections and institutional governance?

MATTHEW LANDAUER: When Socrates praises the “examined life,” he uses the language of accountability familiar to his Athenian audience from their own political culture: institutions like the dokimasia, in which prospective magistrates could be questioned by their fellow citizens about their past actions and behavior, personal and political, before they assumed office; or the euthuna, in which magistrates’ public service was subject to far-reaching scrutiny and review before popular juries. Whatever they thought of the unexamined life, Athenians were deeply hostile to the idea of unexamined magistrates. For some scholars, then, the Socratic practice of philosophy resonates with democratic ideas of openness, critical scrutiny, and deliberation. And some accordingly see Athens as the original deliberative democracy, whose institutions provided for collective decision-making through discussion and the robust exchange of views.

The idea that Athenian institutions realized ideals of mutual accountability and reciprocal deliberation coheres with a central Athenian ideological claim: that democracy means the rejection of tyranny and all it entails. In the Greek political imaginary, the archetypal unaccountable figure is the tyrant. And as Athenian orators were often fond of stressing, in democratic Athens those holding public office, and the politicians offering advice to the demos in the assembly, could always be held to account. This is a seemingly attractive picture of Athenian democracy, with considerable truth to it. But it also overlooks an inconvenient fact: ordinary citizens, participating en masse as voters in the assembly and as jurors in the popular courts, were unaccountable. While they played decisive roles, collectively, in holding other political actors to account, jurors and assemblymen could not be called to account for how they voted.

This is a helpful reminder that real political regimes do not always fit our stereotyped pictures of them. It is easy to imagine “tyranny” as the realm of unaccountable power and the absolute silencing of political speech, while “democracy” is the natural home of accountability and robust political deliberation. But in the ancient Greek world, decision-making in both autocracies and democracies was structured around accountable advisers (sumbouloi) giving counsel to powerful, unaccountable political actors (whether tyrant or the assembled demos). In Greek descriptions of tyrannies, advisers to the ruler often pay with their lives. And a similar dynamic could prevail in democratic Athens. Through procedures such as the graphe paranomon, orators could be held accountable for proposals they made in the assembly, with penalties ranging from slaps on the wrist to crushing fines and even death. It is these moments, when political logics converge across regime types, that alert us to fundamental political structures and problems.

John Kelly reportedly warned Donald Trump that if Trump ever hired a “yes man” to replace him, Trump would be impeached (though Trump denies this: “If he would have said that I would have thrown him out of the office”). Kelly was invoking the need for powerful political actors to hear frank advice: what the Greeks called parrhesia. But Trump’s response illustrates the difficulties of frankly advising powerful, mercurial agents — they might not like what you have to say. Safer, perhaps, is the course taken by Stephanie Grisham, Trump’s press secretary: “I worked with John Kelly, and he was totally unequipped to handle the genius of our great President.” The incentives to flatter a figure like Trump are ever present and powerful. How can decision-makers secure good advice under such conditions? And how can advisers assist decision-makers in their deliberations without endangering themselves? The ancient Greeks were intensely interested in these questions, recognizing them as perennial problems for all political regimes, including democracies. For collective bodies of citizens themselves might act, at least sometimes, more like a tyrant or a Trump than like a utopian deliberative assembly (and Trump himself seems to think that Americans can be swayed by flattery: on the campaign trail he would tell his audience “People don’t know how great you are. People don’t know how smart you are…. These are really the smart people”).

When we find ourselves uncertain, we often rely on the advice of others, whether for information, a recommended course of action, a new framing of the problem, or a previously ignored ethical consideration. But relying on others may also leave us vulnerable to manipulation and deception. Seeking advice forces us to consider whom to trust, and to ask ourselves whether and how we can even recognize good advice and good advisers. It also raises difficult questions about the responsibility for the outcomes of our actions: is my adviser to blame if his suggested course of action turns out disastrously, or is it my fault for listening to him? These questions may arise any time someone with a decision to make seeks out advice: a tyrant deciding whether to go to war, a president in a democratic republic taking counsel from his cabinet of advisers, citizens deciding how to vote in a referendum or an election.

If advice raises interesting questions across political regimes, so too does unaccountability, which plays an important structural role in democratic politics past and present. The secret ballot renders voters unaccountable to ordinary citizens and powerful elites alike. It was originally introduced to protect voters from external pressure and intimidation. But some political theorists are uneasy with this compromise. After all, if voting is a duty, and not a right to be exercised unaccountably, then perhaps our exercise of the franchise should be subject to scrutiny, accountability, and demands for justification. Democratic politics might face competing imperatives: on the one hand, to recognize the basic vulnerability of democratic citizens and to encourage their participation and protect their independence; on the other hand, to recognize that voting is an exercise of power, and that insulating the exercise of power from scrutiny and accountability may predictably engender its own problems. The ancient Greeks, incredibly sophisticated political thinkers and institutional designers, were well aware of such competing imperatives and tradeoffs. Not all good things in politics will always go together.

For both democracy and autocracy, you note a basic bifurcation between decision-makers and those who advise them. You emphasize an oft-overlooked distinction in classical Greek conceptions of deliberation (bouleusis) and advice (sumboulia). You point to Aristotle’s sense of bouleusis as premised upon the capacity to carry out one’s own recommended course of action, and of sumboulia as shaping outcomes by persuading others to act. You point to specific individuals (such as Pericles), to categorical types (such as demagogues), and to a diverse range of political arrangements that each raise, in their own distinct ways, the confounding question of: “When a sumboulos speaks, is he deliberating with his audience?” So here for the fraught questions of how decision-makers come to recognize good advice, how an advisor comes to convince decision-makers of their own limited knowledge or authority or power, how possibilities for frank speech (and potentially for a dynamic back-and-forth exchange) might play out — which particular precedents that Dangerous Counsel cites offer the most illuminating, and most broadly applicable case-studies really for “any regime in which those in power both seek to control subordinates through accountability procedures and rely on them for independent exercises of judgment”?

In the book I discuss many more cases in which advice misfires than cases of conspicuous success. This reflects the Greek view that political counsel is difficult and that we can learn more from reflecting on failure than celebrating success. Take, for example, two key moments during Athens’ fifth-century war with Sparta. In 415 BCE, the Athenian assembly decided to send a massive military expedition against Syracuse, on the island of Sicily. As Thucydides tells the story, the Athenians were ill-informed about the strength of their enemy, the political situation in Sicily, and the resources a successful operation would require. The expedition ended in disaster: of the thousands of soldiers sent, only a handful ever returned home to Athens. The second incident took place in 406 BCE, in the wake of a naval battle at Arginusai in the eastern Mediterranean. After an initial victory, the generals in charge of the Athenian fleet were faced with two imperatives: to follow up with further attacks on the Spartan fleet, and to rescue the sailors on the Athenian ships sunk during the engagement. They decided to do both, tasking subordinate officers with rescuing the sailors. When the weather turned, rescue operations were hampered and many Athenian sailors drowned. Athens quickly launched an investigation. Eventually, after a pair of dramatic assembly meetings, the demos voted to try six generals collectively, by means of a single vote in the assembly; found them guilty of failing to rescue the sailors; and had them executed.

Before embarking for Sicily, and in the wake of Arginusai, the Athenians held assemblies in which ordinary citizens listened to various advisers before voting on a course of action: should we send an expeditionary force to Sicily? And if so, how many soldiers should go? Should we punish the generals for failing to rescue the sailors? Should these generals be tried individually, or as a group? Or should no one be held accountable, with the sailors’ deaths blamed on the unexpected storm?

Much of what we know about each incident comes from Thucydides and Xenophon, respectively. Both dramatize Athenian politicians considering how best to “convince decision-makers of their own limited knowledge or authority or power.” These richly textured scenes of counsel trade on a core insight the Greeks had into the nature of power and its exercise: unless checked, the powerful tend to move from one object of desire to another, always seeking more. This is a familiar trope in Greek depictions of tyrants. As Herodotus tells it, when Cambyses, the king of Persia, was not prevented from marrying his sister, he went on to marry a second sister, too. But ancient authors also applied this trope to the democratic exercise of unaccountable power: Thucydides makes it clear that the Sicilian expedition should be understood as the Athenians’ desire for empire finding a new (unfortunately for them, unattainable) object. Nicias, the Athenian general, speaks against the expedition, and then tries to deter the Athenians by stressing the immensity of the undertaking and the scale of resources required. But his plan backfires spectacularly. On the basis of his advice, Thucydides writes, “everyone alike fell in love with the enterprise.”

In the case of the generals’ trial, when one orator, Callixeinus, proposes trying the generals collectively in the assembly, another politician, Euryptolemus, charges him with making an illegal proposal (the graphe paranomon). Euryptolemus argues that such a trial would be unconstitutional, and tells the assembled Athenians they will regret their decision. But Euryptolemus is shouted down and threatened, with the majority of the assembly insisting that it would be “a terrible thing if someone prevented the people from doing whatever they wished.” Here Xenophon has the assembled demos claim for themselves the tyrant’s power to pursue his own wishes and desires, free from all restraint and accountability. In neither case is good advice, with the aim of chastening power and restraining desire, actually taken. Nonetheless, Euryptolemus’s attempt to stop Callixeinus’s proposal illustrates the importance of having some way to hold advisers accountable. Foregoing procedures for challenging bad advice and sanctioning dangerous proposals invites manipulation and abuse. This remains true even though offloading responsibility for our decisions onto others runs the risk that we will treat our own decision-making power less seriously than we ought to for our own good.

Here these two stories also offer competing perspectives on whether responsibility really can be off-loaded from decision-makers to subordinates. In the Arginusai trial, Callixeinus’s proposals win the day and the generals are tried and executed. But when the Athenians later come to regret the whole affair, the citizens turn their anger against Callixeinus, who dies an outcast in the city. This looks like buck-passing and scapegoating, with ordinary citizens taking advantage of their unaccountability to avoid coming to terms with their own role in the trial. The Sicilian expedition, however, ends differently: the ultimate victims of the assembly’s decision to invade Sicily are the Athenians themselves, who pay for their decision in lost treasure, ships, and lives. Unaccountability, while implicitly understood as an insulation from the consequences of one’s own actions, may in the end be as much a projection or fantasy as it is an enabler of bad behavior.

Well perhaps with projective fantasies still in mind, when you ask whether the sumboulos deliberates with his/her audience, I wonder (recalling Plato’s Phaedrus) the same about a written text. When you describe the sumboulos navigating a complex interpersonal calculus both in autocratic and democratic circumstances, I think of how literary texts always say the exact same thing (and also inevitably differ) from one audience to the next. So could we consider Dangerous Counsel’s account of the Gorgias, in which Socrates fails to articulate (even as Plato perhaps implicitly demonstrates) how a sumboulos might best go about advising those with no foundational sense of the good? What might Plato (himself, of course, no eminent public advisor like a Demosthenes or Aeschines) advise here on how to harness and constrain (if never to correct) the conflicted impulses of the tyrant or the demos? How, precisely, does Plato’s own advice get transmitted? And as one practical take-away for present-day audiences, what might we learn from Socrates’s example about when/how to steer flawed political actors down the most constructive available normative path — rather than seeking to reverse their souls?

In the Gorgias, Socrates tries to convince various conversational partners of the striking, counterintuitive claim that most humans, including leaders in democracies and even tyrants, actually have no power at all. His argument for the claim goes something like this:

1. Power is the ability to get what you really want.

2. Humans really want what is actually good for them, not what merely seems good for them.

3. Most humans (including orators and tyrants) do not know what is really good for them.

4. Acting in ignorance of what is really good is unlikely to achieve what is really good.

5. Therefore, when ignorant orators and tyrants act, they are unlikely to get what is really good for them.

6. Therefore, ignorant orators and tyrants do not really have power.

For Socrates, the most difficult premise to convince interlocutors of is number 3. For instance, I personally don’t believe that I am radically ignorant of my own good. This claim probably sounded as unpromising (and even offensive) to the average Athenian as it does to those of us today who reject the paternalistic notion that others know better than we do what is good for us. Some who aren’t convinced will just see Socrates as deeply weird. Others might take him to be a serious threat to their sense of self and basic values.

Socrates’s argument is a political failure: no one takes it to heart. But it’s worth thinking a little about what Socrates’s failure tells us about the nature of advice. In particular, his focus on radically reorienting souls forces us to think about the time scale of advice and of learning more broadly. Advice accompanies, and attempts to shape and aid, deliberation. And political deliberation is always time-delimited. We often seek advice when we have to act in the relatively short-term: we are considering what we should do now, with our current problems, not what we should do in 10 years’ time. That’s the nature of deliberation and political judgment, which take place under both substantive and procedural constraints. Substantively, sometimes decisions have to be made that cannot wait. Procedurally, we may only get to decide who should represent us in Congress, for example, once every two years — and the main way most of us contribute to that decision is by casting a vote. But these procedural constraints are not something we can do without. They comprise the institutions, practices, and customs that allow us to judge and decide together at all.

While deliberation under constraints is unavoidable, advice aimed solely at aiding constrained deliberation may be inherently limited in what it can effect. We might worry that such advice, for example, will never be able to speak to the big picture. Imagine a friend who always gets into trouble, and whose life seems like an unending parade of problems. When he comes to you seeking counsel about a particular problem, you might offer advice to help him resolve the present crisis. But later, once this problem is resolved, you might also try to help him see aspects of his behavior and choices that could be changed for the better, ideally to prevent further crises from happening at all.

A dialogue like the Gorgias also pushes its readers to reflect on how political learning takes place more broadly. Given Socrates’s failure to convince his interlocutors of their own radical ignorance about the good, some interpreters read the dialogue as fundamentally pessimistic. But I think there is a second strand of argument in the dialogue that may have more political uptake. Socrates does offer a response to those who are skeptical of his argument that orators and tyrants have no power. It takes the following form: those who think they have power should reflect on the experience of others in similar positions. If they do, they will see that the ordinary pursuit of political power often fails on its own terms. This is true for orators in a democratic city, whose quest for influence and leadership often fails badly — again think of Callixeinus, whose life is destroyed when the demos comes to blame him for the Arginusai trial. And it is also true for an imperial city like Athens.

In making this point, Plato employs a neat literary trick. The dialogue is set during the Peloponnesian War, with Athens at the height of its empire. Socrates denigrates the city’s imperial trappings (dockyards, walls, tribute, and treasure) as false goods: the Athenians do not see that, underneath these symbols of imperial might, the city is “festering with sores.” To Socrates’s fifth-century interlocutors, swept up in the glories of empire, this critique might find little purchase. It requires them to deny that what they take to be good (empire and wealth) really is good for them. Yet Plato’s fourth-century readers would have the ultimate failures of the Athenian empire squarely in mind. Good advice is one thing. Being in a position to recognize it and appreciate it is another.

What the dialogue holds out hope for, then, is a kind of mediated learning by experience. We can come to see that certain pursuits we take to be good are likely to fail on their own terms. I don’t think Plato takes this lesson as a given: learning by experience is not automatic, and written texts that capture experience and push us to reflect on it are crucial aids. Platonic dialogues, as you point out, are written texts. And despite the vicissitudes of their reception and publication history, they have been incredibly successful at persisting through time. Socrates says that philosophy always says the same thing to him. But the ability to return again and again to a text, and to be open to learning from it in new ways, makes a different register for advice possible, on a different time scale, operating in a different way than the everyday back-and-forth of deliberation and decision in politics.

Yeah perhaps, as you say, we shouldn’t give an acerbic Plato the last word on Athenian democracy, with its intricately layered politics of accountability. Yet when I picture Athenian idiotai (ordinary citizens) as wielding great power (but only if melded into the group, less authoritative if singled out), as playing a decisive role in Athenian democratic debates (but only by keeping comparatively quiet, giving no account), I again return to the reader, and wonder when Plato might indulge (or enforce) a functional asymmetry that allows (or requires) an all-powerful (or marginal) audience of idiotai to stay silent (or to take a strong stand, as various competing voices clash). So again with the Gorgias in mind, with various interlocutors dropping in and out of the exchange (returning to or from the invisibility of the crowd), how might you see Platonic dialogue creating discursive space for readers to begin reflecting on their own accountability / unaccountability? Or how else might the peculiar vantage posed by reading such dialogues in fact help to prepare us for the rigors of democratic citizenship — for recognizing our dual status as both citizen-subjects who can “only act by considering and deciding on the basis of the logos of others,” and as decision-making authorities “given life in and through the democratic institutions of the polis”?

It’s interesting to think about who we are supposed to empathize and identify with when reading a Platonic dialogue. Are we like the crowd that, in some dialogues, witnesses the conversation? Are we supposed to put ourselves in the interlocutor’s shoes, trying to understand why he answers Socrates’s questions the way he does, while imagining how we might respond differently, or better? Are we supposed to cheer on Socrates as the hero of the story? Not all of these ways of engaging with the text will be equally productive. It can be fun (as presumably it was for witnesses of the historical Socrates, and as some characters in Platonic dialogues gleefully attest) to watch Socrates put someone to the question, to see that person wilt and fade under Socrates’s scrutiny, finally to collapse in utter confusion. But if what we get from witnessing the exchange is an (unearned) sense of superiority, then it is doubtful that we have learned anything of value at all.

More promising, perhaps, is the way in which Platonic dialogues seem to invite their readers into a different world (or perhaps just a different way of seeing the world). Characters in these dialogues often point to the setting in which the conversation takes place. And often these conversations take place in privileged spaces, where participants are freed from the constraints of public speaking. Again, orators in the Athenian assembly were accountable for their advice, and could be punished for advising poorly. But as Socrates says in the Republic, the only punishment appropriate for someone who says the wrong thing in a philosophical conversation is actually a reward: refutation, or the (sometimes painful, but salutary) process of coming to learn something true and letting go of false opinions.

For some readers, this might suggest Socratic and Platonic philosophy’s potential to produce new, oppositional spaces and publics capable of sustaining a better way of life — or even, in the fullness of time, capable of transforming mainstream culture and politics. These spaces and discourses might look either elitist or democratic-insurgent, depending on one’s imaginative proclivities and interpretations of Plato.

But from a different vantage point, philosophical spaces and conversations might just look weird and kind of sad. Callicles, the most challenging of Socrates’s interlocutors in the Gorgias, doesn’t think much of philosophy’s counter-spaces. He dismisses Socrates as just an older man whispering with boys in some dark corner. Socrates counterpunches with a dismissive and powerful image of his own. Foreshadowing his own trial, Socrates says that if he ever had to face a popular jury, it would be like a doctor being tried by a pastry chef in front of an audience of children. He imagines the prosecutor saying: “Children, this fellow has done you all a great deal of personal mischief, and he destroys even the youngest of you by cutting and burning, and starves and chokes you to distraction, giving you nasty bitter draughts and forcing you to fast and thirst; not like me, who used to gorge you with abundance of nice things of every sort.” If the doctor then replied: “All this I did, my boys, for your health!” would he escape punishment? If not, then the democratic public sphere, institutionalized in the assemblies and courts (and in which Callicles wishes to play a leading role), is dismissed as deeply pathological.

So one possible response is to retreat to a pessimistic reading of the dialogues: Socrates, and philosophy, have nothing to say for politics. There is no way to make politics responsive to reason, and no possibility for democratic citizens to be responsible, prudent, and receptive to good advice. But I think this would be a bad reading of Plato, a poor conclusion to draw from engaging with the broader ancient Greek tradition, and a dangerously defeatist approach to democratic politics. The political problems we face arise from patterns of human decisions, actions, and institutions. These patterns are not fixed and immutable. Socrates suggests that even the jurors who voted to kill him might have chosen differently if they had been able to talk with him a little while longer, under different circumstances. Democratic politics requires a public sphere in which both accountability and good advice can flourish — constructing and maintaining that space is up to us.