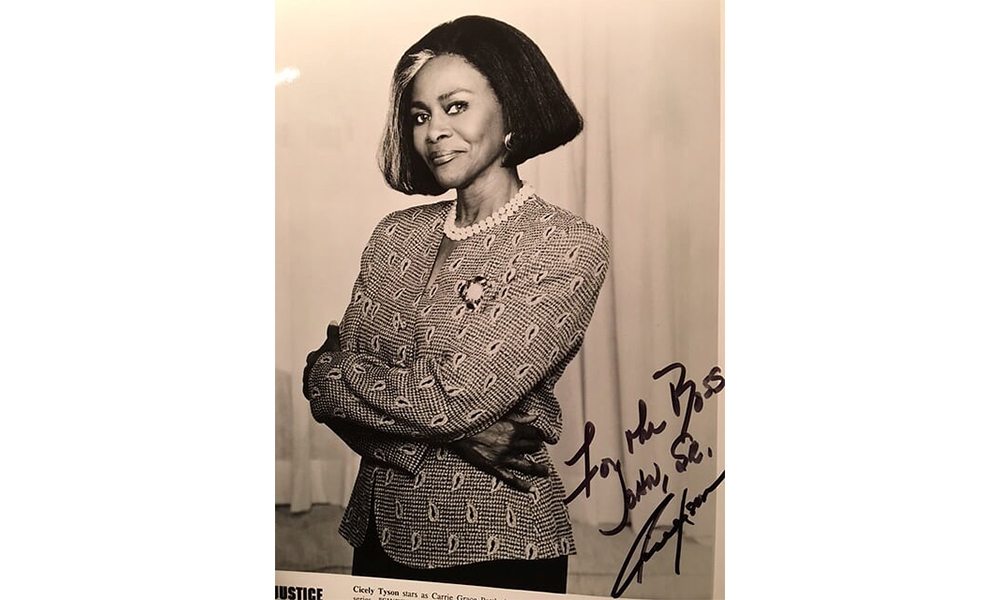

In 1994, I created and ran a show on NBC called Sweet Justice in which Cicely Tyson, whose passing last week has moved me to write up these thoughts, played a civil-rights lawyer in the South. Her junior partner in the office was Melissa Gilbert, and we surrounded them with a talented cast, including the redoubtable Ronny Cox as Cicely’s right-wing nemesis. We shot in New Orleans and Los Angeles, had loads of fun along with the usual stresses and strains, and went down fighting after a year on the air: our fans were too few, but they were passionate.

Perhaps I should rather call them “Cicely’s fans.” She garnered an Emmy nomination for her performance, which was deep and (the inevitable word) graceful, but I must add at once that she fought always to be sure the show was sending the racial/political message which had lured her into the role of “Dorothy Battle” in the first place. I could count on her showing up at my office door whenever a new script was released, to argue for changes, not only in her scenes but throughout the script — and they were nearly always of a kind that sharpened the edge of what we had to say about the issues for the sake of which she’d taken the part, as a Black woman. She was a woman who moved, I would find, in the highest circles of national affairs when it came to race and the arts in general.

Other producers who’d worked with her had warned me I’d be on the receiving end of such office-visits, but I took nothing but pleasure in them, took active pride in how this preeminent actor treated a little network drama that virtually no one was watching (despite the fine writing by such newcomers as Ed Redlich and Gina Prince) as seriously as if she were doing Genet’s “The Blacks” at the Kennedy Center. We took pride, too, when we heard that then-First Lady Hilary Clinton rarely missed an episode, and it won’t surprise you to hear that there was great excitement the day Rosa Parks paid a visit to her friend Cicely on our set in Culver City. I’d like to think Ms. Parks’ reason went beyond their friendship and had to do with the fact that we were saying something worth hearing.

On a lighter note, I’ll never forget her positively girlish delight when we chose the suave, gifted Michael Warren, my friend from our days on Hill Street Blues, to play her love interest. And likewise it makes me smile to remember the day when Cicely was in my office, working over a scene, and I received a phone call from Vernon Jordan, the prominent civil-rights leader then serving as a close advisor to President Clinton. He was trying to reach Cicely, with whom he had, as I was soon to learn, a teasing, brother-sister relationship. When I assured him she was there in my office, he mock-chastened me in ringing tones, “You’ve got Cicely Tyson with you? Young man, didn’t your mama ever tell you you are judged by the company you keep?” Cicely laughed and kept laughing…

But my fondest memory is of a day that came at the end of our season together. Long months earlier, I should tell you, I had learned a painful lesson: she wouldn’t hear a word about Miles Davis, to whom she had been married for a time — unhappily, it is said. Not knowing this, and having wide-eyed, fan-boy reverence for the great man, I couldn’t help, as Cicely and I got to know each other, asking the occasional question about him. Apparently I was too thick to correctly interpret how little she would say in reply. Then one day a set-designer took the liberty of mounting on the wall of our set, in the very office of the lawyer Cicely was playing, a poster which consisted of the enlarged cover of “Sorcerer,” one of Miles’ classic “crossover” recordings, which featured a (beautiful) profile photograph of Cicely from 20 years earlier. When she saw it, Cicely hit the roof. Convinced that someone was deliberately taunting her, she complained to me at full throttle, even after I had the poster removed.

The episode left me shaken — she was good at hitting the roof — and I resolved, as well she knew, never to bring up his name in her presence again, and forbid cast and crew to do the same. A few days after Sweet Justice was cancelled — the show which Cicely and I both loved and into which we had poured so much of ourselves — my assistant came to me in my office late one afternoon to tell me that on the other side of the Sony lot a limousine had arrived to take Cicely to the airport. She was flying home to New York, never inclined, as it happened, to spend more time than necessary in Los Angeles. She would be pleased, I was informed, if I would stop by and say goodbye to her. I hurried as fast as I could.

I can still see the limousine waiting, in the failing light of day, its door hanging open, and Cicely, just past 70 then, standing beside it with her sublime ex-dancer’s stillness, her gloved hands folded before her, as I ran up, rehearsing under my breath some doubtless unremarkable words of parting and a promise to keep in touch. But the words never left my mouth. Before I could utter a sound, she took my arm and led me off on a walk, from the first steps of which she did the talking — all of it — in that melodious voice we all know or can recall. “I first met Miles…” she began, and for most of an hour (I’m guessing, I lost all sense of time) she regaled me unprompted with what she knew I longed to hear, stories of Miles’s recording sessions, of friends like Cannonball Adderley and Coltrane, of nights on the road or in her beloved Manhattan. She even took me into the Sony store, which was opened at her request at that late hour, so she could flip through the legendary CDs in the sales bin (since his label, Columbia Records, was now part of Sony). Every cover brought a different story. She was in no hurry; she was making a present to me of memories which no doubt, in part, were painful, in order to show her appreciation of the year we had spent, and the privilege we had shared of putting on the screen a message of racial equality and the fight for justice, which was our purpose from first to last. I delivered her to her limo driver, quite robbed of any capacity to express how much our “walk & talk,” as we call it when we’re filming, had meant to me. So I only said, “Goodbye and thank you,” and left the full measure of my gratitude unspoken until now.