Now that the stench of Donald Trump’s odious reign has reached the far corners of the globe, infecting everything not just political but cultural, it was inevitable that this year’s Les Rencontres d’Arles, the most elaborate and prestigiously curated photography festival in Europe, should include a good many exhibitions that in one way or another reflect his malignant zeitgeist. To anyone steeped in legit daily news media, it was impossible not to view much of the festival’s presentation through that bleak lens.

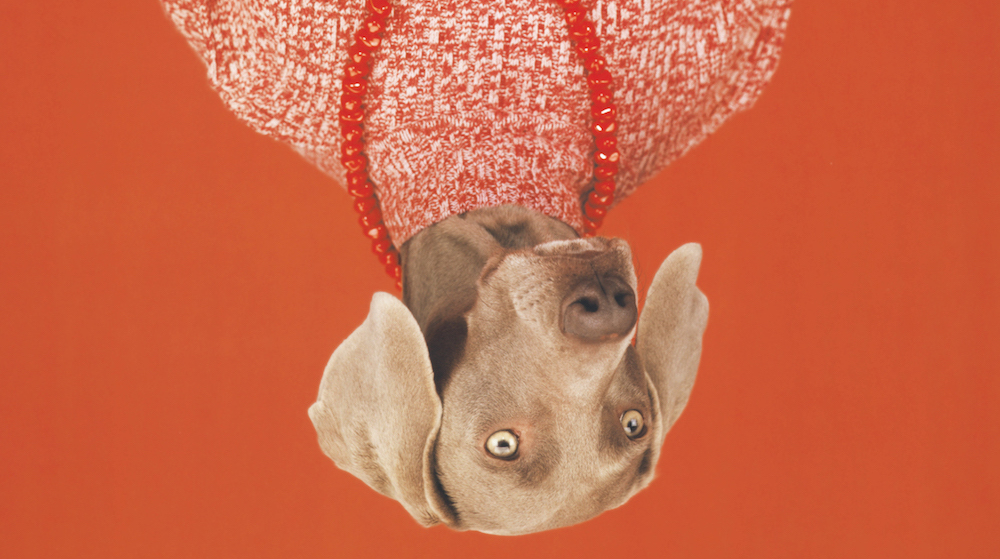

As the annual summer mecca of all things photographic, Arles welcomed 17,500 image-seekers in the opening week of its 48th edition, which included a provocative constellation of 40 exhibitions of 250 artists’ work in 25 venues around town (many of them the sublime re-repurposed spaces of ancient churches) — along with a sweeping program of panels, conferences, workshops, and visually mesmerizing evening gatherings in its Roman amphitheater. (The town’s other major Roman relic, a working coliseum, still, sadly, holds bullfights every spring.) The entire enterprise has been bolstered by the empire-building vision of Maja Hoffmann, the Swiss pharmaceutical heiress whose arts-nurturing Luma Foundation has turned a complex of warehouses and de-commissioned train garages into a vast compound of galleries, bookshops, eateries, and other cultural spaces. The festival even has satellite events in Marseille, Barcelona, and China. Arles’s offerings are now expanding into dance (with resident choreographer Benjamin Millepied), theater, and other media (VR is now a regular feature). The coup de grâce, a metallic Tower of Babel-like edifice designed by Frank Gehry, opens next year and will surely solidify Arles as an obligatory destination on the art-world circuit — especially as photography hastens its migration into mainstream art dialogue and valuation.

Outside of fascist and white-supremacist ranks (swelled by the continent’s migrant crisis), a percentage of aristocrats clinging to privilege, anarchists who just like to see institutions blow up, and probably a few brutish males who like his style of pushing women around, most Europeans despise or at least find reason to ridicule President Trump. Yet they continue to welcome Americans, and feel political kinship with the United States, presuming that Trump and his gang are an unfortunate aberration. Several exhibitions at Arles this year celebrate an America that foreign countries understandably feel nostalgic about, an America perceived as having balanced its postwar military might with a benevolence of doctrine and purpose, a humane beacon to the world’s afflicted. From the outside, America was great. Close to the truth or not, everyone wanted to live there, or envied those who did. Today, not so much, as Trump insults allies, courts despots, thwarts immigration, and plays dangerous games with Europe’s unity, economy, and security.

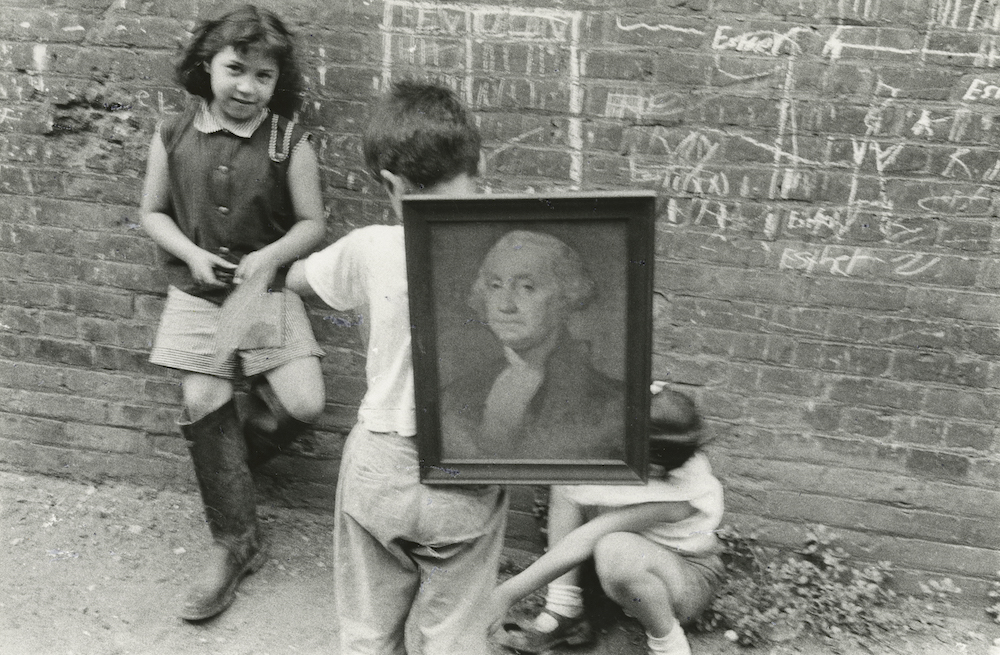

So there is much looking back to 20th-century America, often through the eyes of outsiders. Robert Frank’s seminal 1958-1959 book, The Americans (first published in France as Les Américains by the legendary Robert Delpire), consisted of 83 photographs selected from over 20,000 that he shot on meandering road trips in 1955, a fraternal echo of Jack Kerouac’s Beat-blooded classic, On The Road (1957). Swiss-born, Frank was the first European to be given a grant to document regional American life, and he did so candidly and unsentimentally (so much so that the book was widely attacked as overly critical for revealing signs of racism, bogus patriotism and religiosity, and tawdry consumerism). The Arles show adds images not in the book, many prior to The Americans as he was honing his skill and his wry eye, and pushing the camera’s boundaries — as well as the continuous screening of Don’t Blink (2015) by Laura Israel, an irreverent, jauntily intimate film with and about Frank. It’s always a revelation to re-see, and re-think, images relegated to iconic status, if a new context is provided, particularly this landmark disruption of photography’s rulebook. Seen against the daily horrors of Trump’s shady governance, Frank’s America becomes a surreal flashback dramedy of vintage characters as diverting as an HBO period series, even as it illuminates a master’s earliest intuitions.

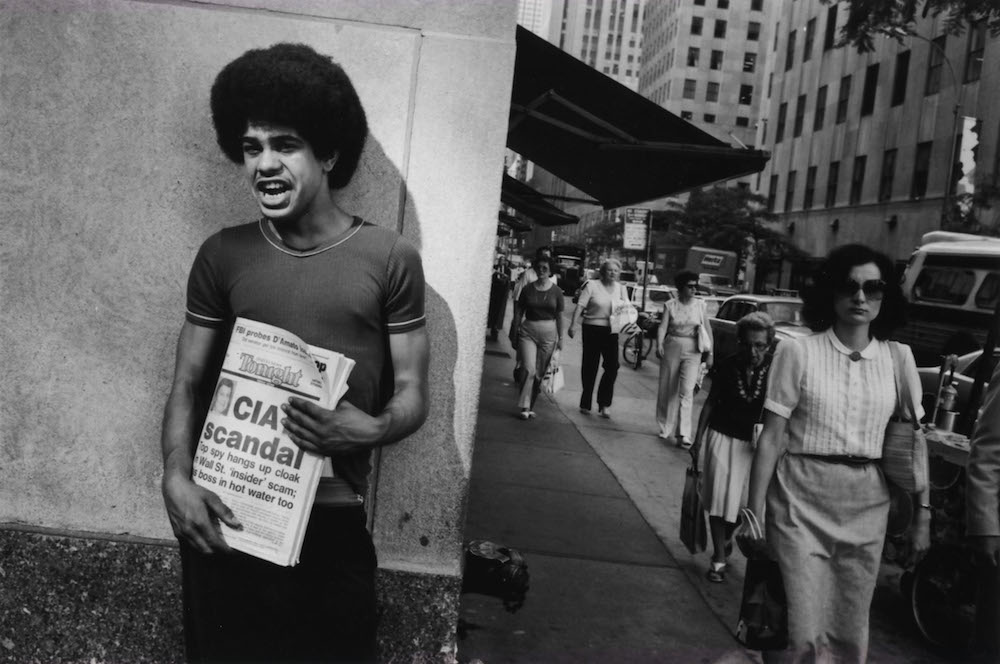

Another European, veteran Magnum photographer and filmmaker, Raymond Depardon, began roaming America in 1968 while covering the Democratic National Convention in Chicago, an anti-Vietnam War demonstration, and Nixon’s winning electoral campaign — continuing his exploration of American life on and off through 1999, the year he created vertical-format landscapes of Montana and South Dakota. He embraced the more freewheeling photojournalism of his American colleagues, evolving his own spontaneous approach and personal vision. His exhibition at Arles, Raymond Depardon USA, 1968-1999, offers as wistful a view as Frank’s of a less rancorously divided United States, even given the political tumult of the 1960s. As we gaze at his off-the-cuff shots on city streets, in diners, at vacation stops, the world at that time seems less fraught. His image of Nixon flashing his signature double-V, dwarfed by an American flag, bears rueful witness to a time when a US President was duly held accountable for misdeeds that now seem comparatively innocuous.

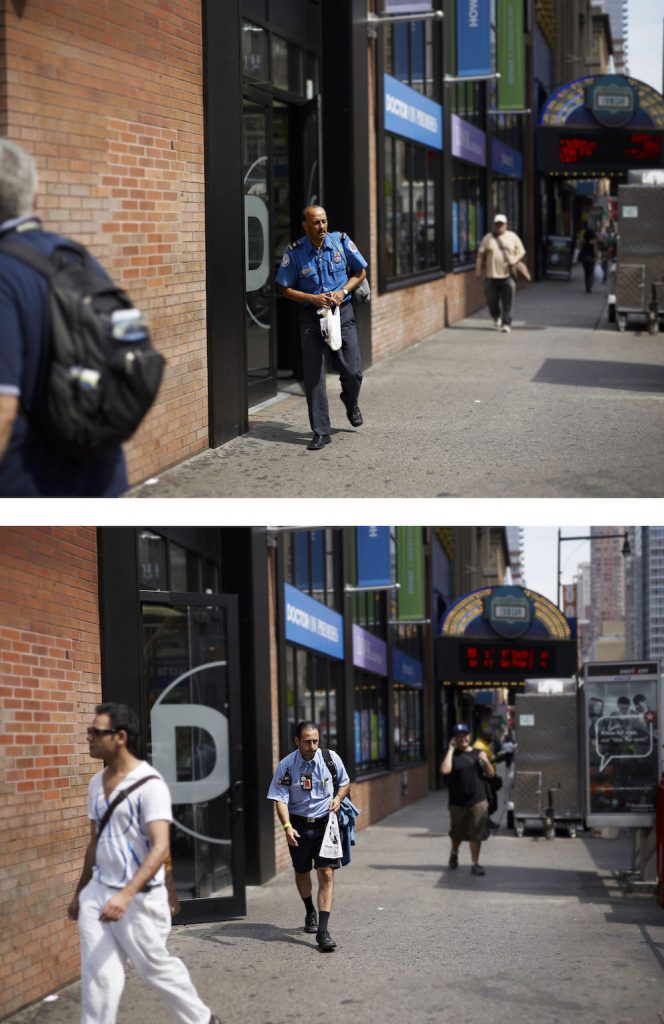

The British photographer Paul Graham landed in America in 1998 and over the next dozen years produced an informal trilogy of works ranging from single large-scale photographs to sequences of over 20 images that zeroed-in on evidence of racial and social inequality. In American Night, he alternated pictures over-exposed to the point of near-imperceptibility with full-color shots, as a kind of metaphor of America’s tacit class divide. Graham’s sequences also made study of the inherent stutter of perception that occurs from moment to moment, mostly in the casual hypnogogy of strolling along urban walkways. These images are more surgically directed at an underclass plight than those of street photographers like Winogrand or Meyerowitz, which can’t help but foreshadow the economic malaise that cyclically recurs in the United States, but which has been so errantly ignored, indeed exacerbated, by the current administration.

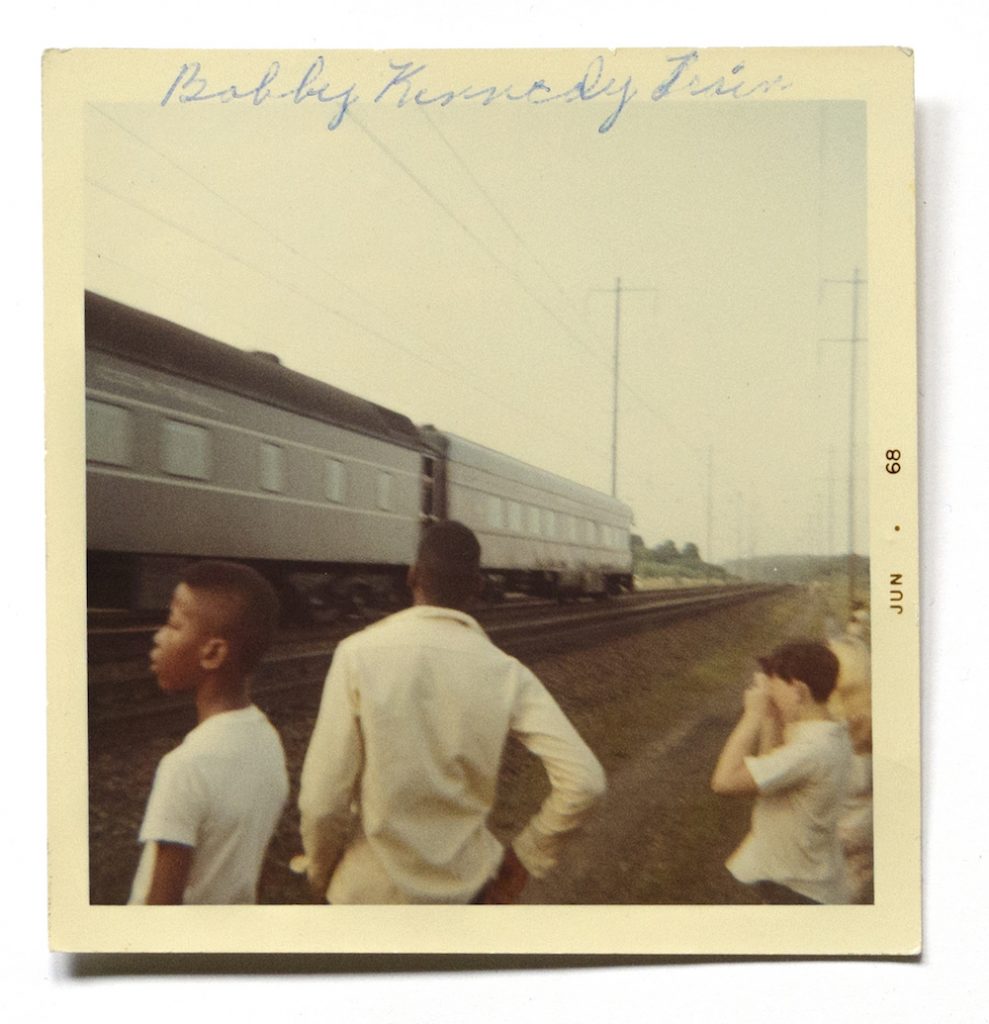

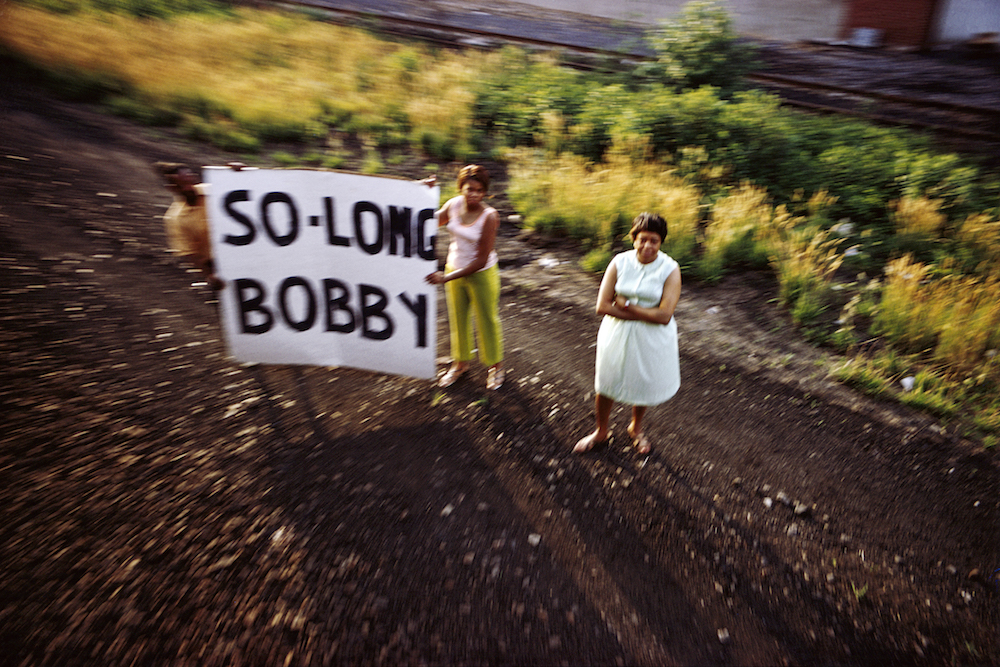

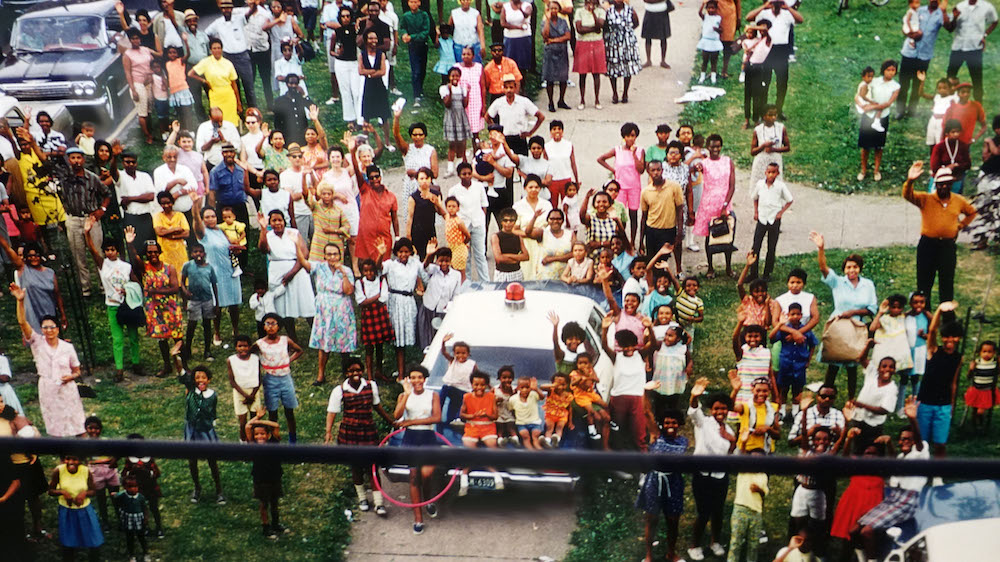

On June 8, 1968, three days after the assassination of Robert F. Kennedy, his body was transported by a funeral train from New York City to Washington, D.C. A poignant half-century commemoration of this solemn rite, The Train, is eloquently presented at Arles in a three-part exhibition. Paul Fusco shot photos from the train, capturing a melancholy medley of mourners paying respects along the railway path, a cross-country wake that seemed to unify the country in bereavement over the abrupt loss of a beloved and increasingly enlightened leader. Where are the revered leaders of today, one might ask as the faces of citizens of every class and color grieve openly from one wall to the next. Dutch artist Rein Jelle Terpstra flipped the perspective by scavenging for amateur photos and home movies by the spectators themselves, in The People’s View (2014-18), long before smart phones refined and proliferated such personal records of historic events. French artist Philippe Parreno, a constant in lofty art venues, created a 70mm film reenactment of the train’s journey, which Parreno has said “shows the point of view of the dead.” Seen as a whole, this multidisciplinary tribute to a fallen knight of Camelot, America’s collective dream of redemption for decades to come, is a moving exercise in deciphering national memory.

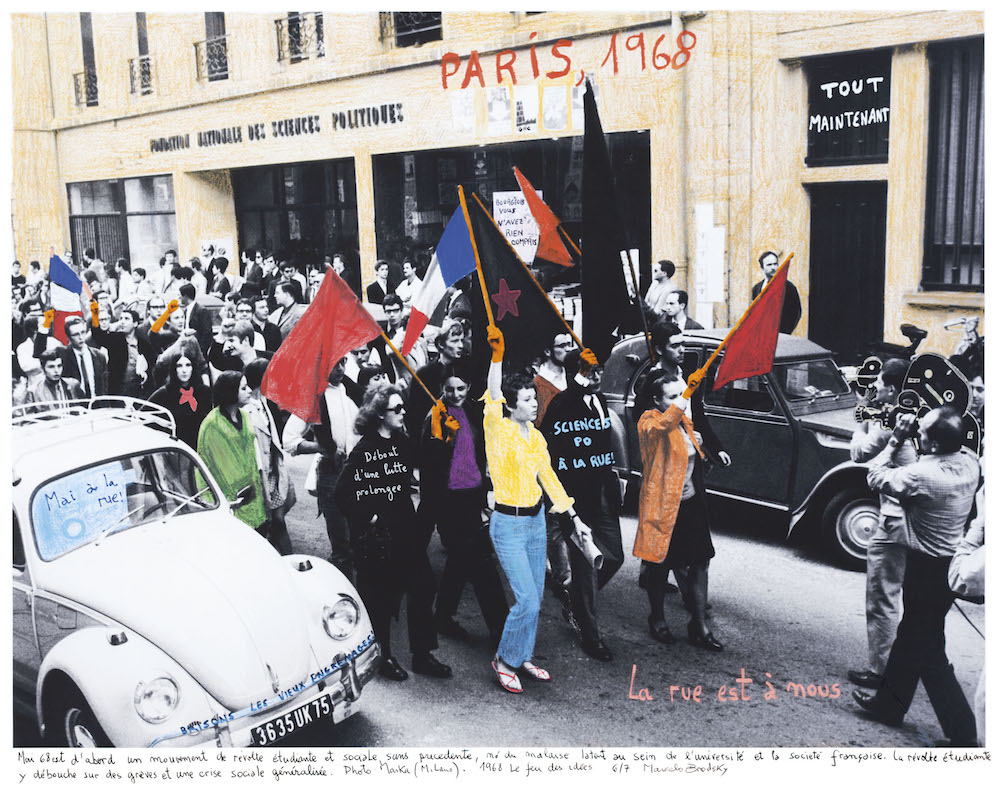

1968 was a year of violent upheaval not just in the United States, where Martin Luther King Jr also was assassinated and Mayor Daley’s cops rampaged against protesters at the Chicago Democratic National Convention — but around the globe. Nowhere was more gripped by civil conflict than Paris, where in May the crescendoing confrontation between police and a loose coalition of students, workers, and artists, ended in city-wide barricades, widespread riots, destruction of property, and heavy injuries on both sides. As in the United States, it saw the emergence of a highly politicized youth generation ready to take on the establishment and fully commit to protesting against an Indochina conflict that France had already abandoned, as well as a general tide for social change, sexual liberation, rejection of materialist values, etc. Universities were shut down, and civil unrest eventually led to hurled cobblestones and assault in both directions. The exhibition 1968, What A Story! uses period posters, documents, police archives, the year’s covers of Paris Match, and an extraordinary collection of photographs (including one of that era’s French cinema maîtres Truffaut, Godard, Lelouch, and Polanski shutting down the Cannes Film Festival in solidarity with the biggest general strike since the post-war period). It can’t help but strike a chord with anyone pondering America’s present resistance movement, with its plethora of homespun graphics, Antifa, arms-obsessed right-wing groups, and the what-if mutterings on both sides about revolution and civil war. One of the program highlights was a staged conversation with May 1968 firebrand Daniel Cohn-Bendit, who invoked that distant incendiary episode’s relevance to the world’s simmering rejection of Trumpism.

Anyone who has asked how Trump stays in power (and who hasn’t?) eventually comes upon that recalcitrant base element, the Evangelicals. He’s been deemed by them a righteous gift from God, and no act however moronic, mean, or self-serving will shake their faith that this blustering conman is anything but anointed to save America. Which brings particular pertinence to Norwegian filmmaker Jonas Bendiksen’s visual survey of the false messiahs he tracked around the world, The Last Testament (2017). His project took him from a peripatetic Zambian faux-Christ who regularly gets jeered and pummeled, to a British ex-M15 agent who has transmogrified into a shabby transvestite savior, to a Philippine prophet who has built a vast media empire, with its millions-strong devotees, which is so fortress-like that Bendiksen could only capture him off a TV screen. Several so-called “prophets,” bearded and archaically draped, even look a bit like Jesus. What is best revealed, in a manner both comical and troubling, is how credulous and easily hypnotized their flocks seem — lives so devoid of moral ballast as to fall prey to the phony religious rantings of grifters and madmen. A phenomenon now all too familiar, and implacable, at the far-right end of the US voting spectrum.

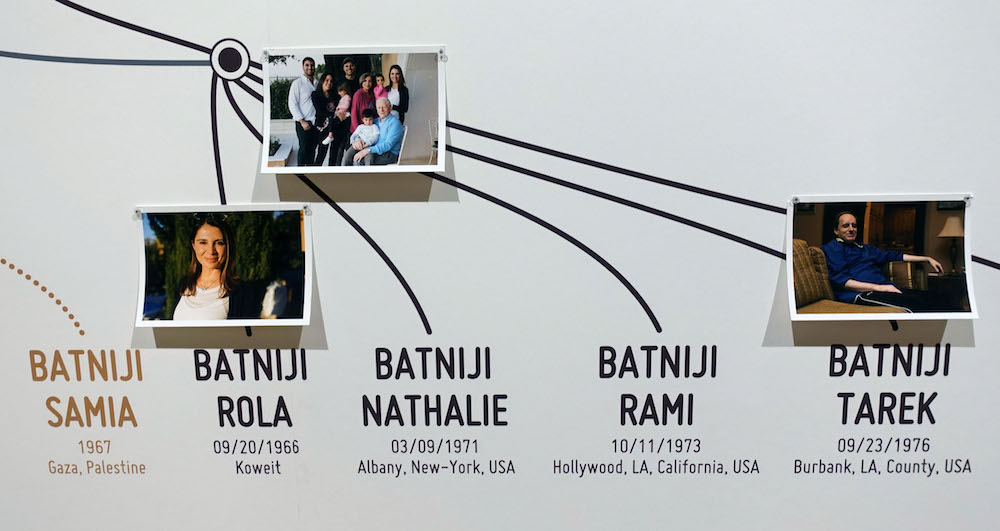

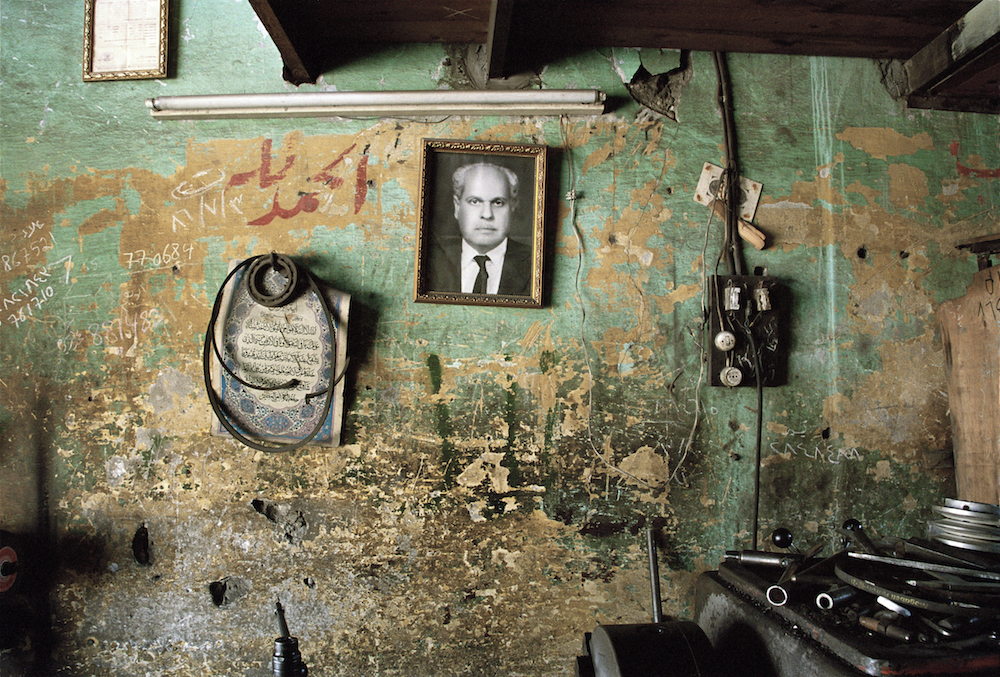

To many, Trump’s most grievous diplomatic blunder, the recent Helsinki debacle notwithstanding, was shoving the American Embassy over into Jerusalem (and more recent support of the Netanyahu government’s spate of laws privileging Jews over non-Jews). An affront not only to the Arab world and to moderate Jews worldwide, in arrogant defiance of prudent precedent and most career diplomats’ positions, it further racheted up Israel’s hotly-debated ill treatment of its Palestinian population. In Arles, a retrospective of Palestinian Taysir Batniji’s work serves to amplify and articulate his people’s drowned out voices and oppressed lives. In one section, bombed-out Palestinian homes are re-framed as mock real-estate ads. In another, the typological grids of Bernd and Hilla Becher are deployed in displays of Israeli military watchtowers. And in the main section — Gaza to America, Home Away From Home — Batniji points to the hot-button issue of immigration in America (and how class is factored into who is welcome and who is repelled) by deftly documenting the lives of his own extended clan, physicians and merchants living prosperously with their families in Southern California and Florida. Far from the conflict endured by their countrymen, their Americanization almost total, they nonetheless wrestle with divided allegiances. For Batniji, as for most of the photographers celebrated at Arles, the personal is unavoidably political.