Inside the Belgian pavilion at the 57th Venice Biennale, it is the vast whiteness of the space that strikes you first. The interior of the recently renovated pavilion resembles a hospital, a place devoted to purity, a sanctuary for healing. Then the gaze shifts its focus onto images: Dirk Braeckman’s dark canvases feature bodies, natural formations, surfaces of things so dark that they seem indiscernible from their backgrounds. Rarely has the contrast between space and artwork influenced me quite this way, certainly no other pavilion in the world’s leading art event had come close to the experience.

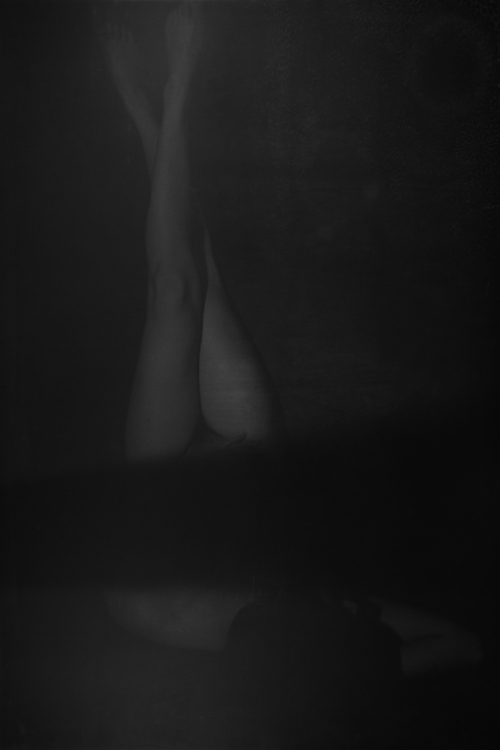

These are intimate pictures, presenting us with a chance to enjoy the private lives of shadowy details. They feature hidden clues and untold stories. One reminded me of that great practitioner of the French nouveau roman Alain Robbe-Grillet, and his novel about an obsessively jealous man, La Jalouisie, the word play in the title referring both to shutters and the jealous husband. In this Braeckman photograph, a naked woman lies on the floor, her legs held high up, a shadow running over her abdomen. This is the story of the gaze waiting to unfold before our eyes, and by looking, we set the story in motion while becoming accomplices as viewers. There is something uncanny about the woman’s face, I noticed; it is difficult to tell whether it is covered by her hair or if she has been kidnapped and hooded. The gaze is divided between viewable parts of her body and the shadow that cuts the body into two. The feeling of watching beneath the shutters adds a chilling, Peeping Tom quality to the image.

180 x 120 cm, gelatin silver print

© Dirk Braeckman / Courtesy of Zeno X Gallery, Antwerp

The pleasures of the glimpse, this is what Braeckman’s works offer us. Their matte surfaces have been created in the darkroom, the prints derived from negatives Braeckman takes at home, on streets, during journeys. There is an unnerving slowness inscribed in them: the photographs are the product of a patient gaze, so masterfully composed that an image may appear like the product of a momentary glimpse. Through the power of the storytelling gaze, we look at curtains, carpets, shadowy interiors. There is little information about the locations or dates of these images, and yet wandering in the Belgian pavilion fills one with tension. The world of details is terrifying with its potential for numberless tales: we are unsettled, in the same way David Lynch’s sudden zoom into the lawn in the opening sequence of Blue Velvet unsettles the viewer.

Most of the works exhibited at the Belgian pavilion are life-size gelatin silver prints on baryta paper. In an interview, Braeckman has described his work in the past three decades as “an implicit response to the multitude and speed of images today.” For him, slowness and resistance are the core elements of photography. Before working on them, he puts aside his negatives for many years. In Slowness, Milan Kundera writes about how “there is a secret bond between slowness and memory, between speed and forgetting.” I had no intention to write about Braeckman but upon returning to Istanbul from Venice, his images haunted me as I lay on my bed at night, watching the ceiling, seeing shadows and lights of passing cars. The slowness that went into their composition has turned them strangely memorable, my mind refusing to move away from their shadowy surfaces.

I imagined how Braeckman would photograph my room, the cracks on its walls, the creases on my pillow. I wondered about the potentials of his patient gaze. One image shows a plastic window frame with double glass. “This is an example of something very trivial,” Braeckman says. “A building, curtains. But what matters is the way you take the photo, your point of view.”

Slowness is Braeckman’s point of view and that makes him something of an exception in the age of Instagram. In Venice I watched art viewers posting their finds on social media, seconds after taking their images. Why the hurry? In a 2017 work, Braeckman shows a glimmer of light on a wave washing the shore. The waves seem to belong to the distant past, one can imagine the ebbs and flows against a historical background. The moment appears to be accidentally caught on camera, but in closer inspection, the mirage-like illumination seems carefully conceived, even manufactured. Such is the fruit of a devotion to slowness. One imagines wave after wave hitting the shore as Braeckman captures them patiently, existing in a present moment that will turn into a memory, an artifact of the past in the future. The artist will return to that moment years afterward and locate in them that moment of unique illumination. A rag-picker of moments long past, his world radiates an unceasing sense of being in the present time.

180 x 120 cm, gelatin silver print

© Dirk Braeckman / Courtesy of Zeno X Gallery, Antwerp

There are no explicit themes in this exhibition, no overarching idea serves here as an organizing principle. But a sense of nakedness runs through all the works here: there are photographs of freshly developed photographs, others of landscapes untouched, the witnesses of the world of the mundane. Their monumental format of 180×120 cm makes the rawness of these works more striking, makes them linger in the mind.

“The matt gelatin silver prints in shades of grey on baryta paper are highly tactile and are also fragile,” writes Eva Wittocx, the curator of the Belgian Pavilion. “Graininess, spots, cropping and flattening of perspective resist an immediate reading or interpretation of his work. Over- and underexposure and working in grey tones heighten the iconic character of his images […] Braeckman’s work places looking at its heart. It is radical and constantly interrogates itself.”

Where does this radical interrogation take us? On the face of it, we are expected to complete the images, bring their stories to a closure, but this reveals itself to be an illusion. In fact, we are expected, as viewers, to partake in the image’s lack of closure. Take this photograph that features an oriental rug, a deserted artefact placed inside an uncanny room. There is a distance between the camera and the rug and that space becomes ours for focusing on the materiality of the rug. We start looking for traces once our gaze is fixed too much on a scene, an object, a person: our imagination plays tricks of perception. Suddenly, in another part of the Belgian pavilion, a set of perfectly ordinary bathroom tiles gather unforeseen significance. The mere fact of their existence turns into an unsettling fact: they become the bathroom tiles of our memories, in their patterns we find glimpses of our personal histories.

“The story of each image is made by looking at them,” Braeckman has told Aperture magazine in an interview. What do these tiles tell us is our business; layers of stories are abound in the nonplaces that he photographs. They are sign and symbol in the same instance, as Oscar Wilde would put it. Surely his preface to The Picture of Dorian Gray whispers to the visitor some of the secrets of these photographs: “It is the spectator, and not life, that art really mirrors.” Braeckman’s posters, curtains and carpets, those mirrors of the self, reveal us our characters in all their anxieties and fears, jealousies and uncertainties. They are books waiting to be read patiently. They bring together the gazes of lovers on their surfaces, so visit the Gardini with someone you adore. These images become labyrinths of life’s unexplored possibilities.

Header Image: Installation view Belgian Pavilion, 57th International Art Exhibition , La Biennale di Venezia, 2017

© Dirk Braeckman