Photographs of photographs constitute a peculiarly self-conscious genre. These images often emit a jejune urgency, an automatic feeling that the photographs they depict must be preserved. Given the rapid transformation of the photographic medium, it’s noteworthy that a physical photograph no longer qualifies as a preservation in and of itself — there must be a digital replication of the object. Photos are taken so that information can be shared (one thinks now of the reliable screenshot) — or so that information can be destroyed, the simulated a proxy for the actual. Sometimes, a photograph of a photograph implies historical and psychic gulfs between both beholders. As Zoe Leonard’s latest exhibit shows, these photographs can bear witnesses to — and perform in — the mysterious drama that is memory.

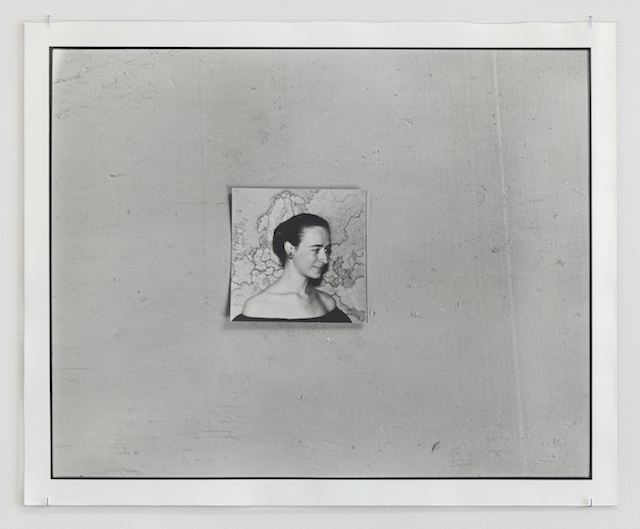

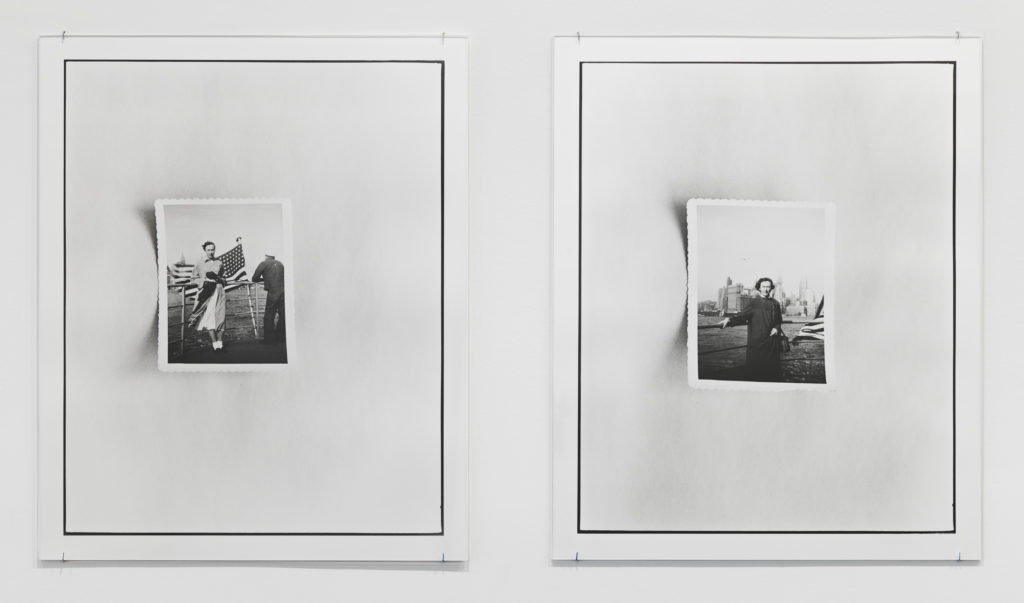

In the Wake, a multimedia exhibit of photography and sculpture now occupying three floors of Hauser & Wirth’s townhouse gallery in New York, consists primarily of retaken photographs. They are ephemeral documents, some glimpsed through the aperture of a Brownie camera, of her family’s postwar emigration from Warsaw to Italy, and finally to America. Its title refers to pictures of her relatives on boats floating serenely in the sea, but also evokes the posthumous tinge that awaits all portraiture. Placelessness and loss are motifs that dominate the exhibit from the start. The first work one encounters after entering the gallery is a framed image of a square, black and white photograph: a woman — supposedly a relative of Leonard’s — whose features gently echo those of Frida Kahlo, photographed against a backdrop of a European map, the cut of her shirt revealing a graceful clavicle, her lips held in an uncertain simper. Who is she, and where is she going? Where has she been? In the Wake keeps destinies unfound, answers none of our pressing questions.

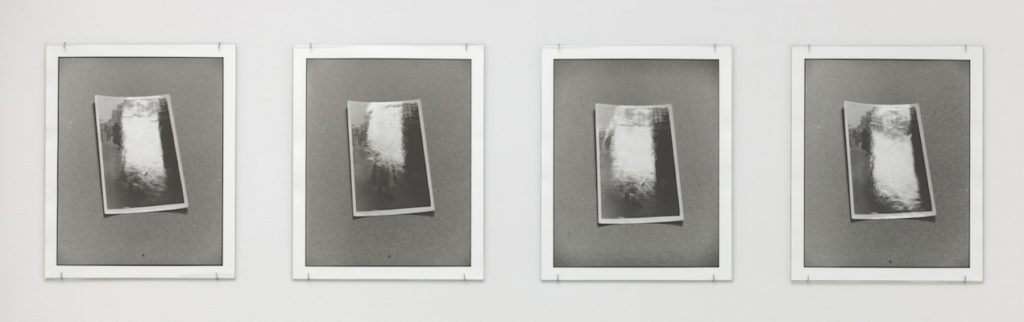

Leonard refuses objectivity by reclaiming the objecthood of these snapshots. Her subject is the palpable image, the developed photo that exists in real space. In literal terms, most of the borrowed imagery in the show barely casts a shadow. Many photos are faded, torn, or obscured. In their physical flaws they accrue additional meaning and history, and Leonard often eschews preservation for interpretation. In “Misia, postwar” (all works 2016), a quartet of snapshots — each the same exact portrait of a woman on the street, in individual frames — the surface glare bleaches the subject, exposing the dimpled wave of a postmark instead of the woman’s expression or stance.

The tactility of images is disappearing. Those of us who contribute to the literal billions of photos taken each day are not doing so with intentions of escorting them into the physical realm. The cost of the medium’s increasing immateriality is postponed — images are taken thoughtlessly, and those with deeper nostalgic or historic value, like Leonard’s family snapshots, will less likely be passed down for generations, relegated instead to the abstract limbo of remote internet servers, the depths of great-grandparents’ Instagram feeds. Whereas the lifespan of a haptic photograph may belong to multiple owners and interpretations, the picture taken with a phone is too often fated to live behind a screen. In the Wake affirms that the print photograph’s history is not confined to what is portrays, but instead spreads onto the material itself. As it ages, the past it aims to package is distorted, its worth in the world appraised by the condition of its surface.

Every snapshot is a quarantine, ferrying experiences and memories into the graspable photograph, adding four edges where there had previously been none. By rephotographing familial artifacts, Leonard is inevitably asking why they were taken in the first place and why they are now being retaken. No answers are volunteered; there is no wall text; titles and names of people are not displayed alongside the works. Taking pictures is permitted in the gallery, though, and I often found myself, perhaps drawn to the messy authorship involved, using my phone to photograph her photographs of photographs.

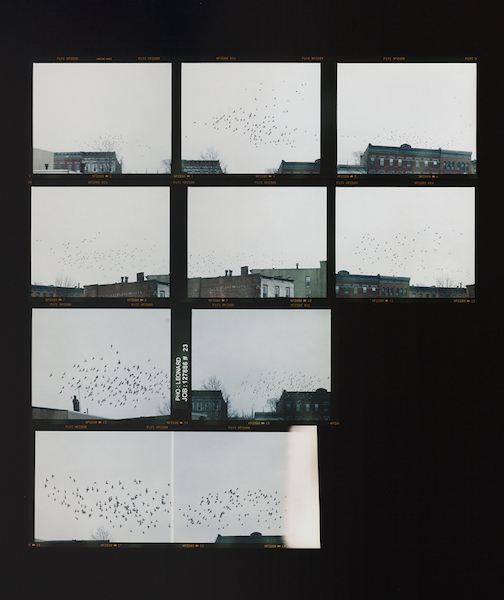

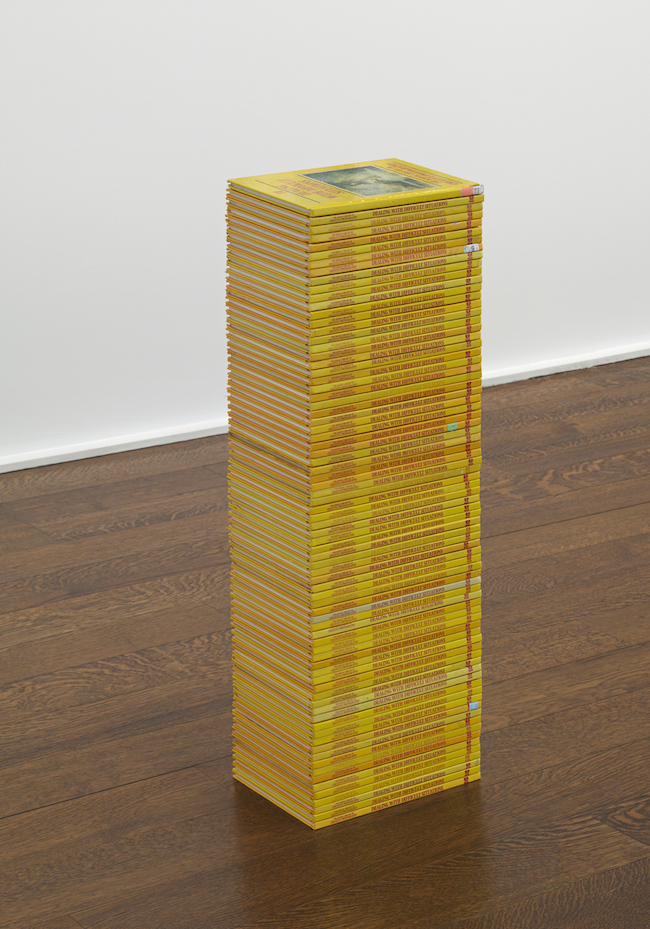

On each floor of the exhibit, old editions of photography manuals for amateurs — titles include Dealing With Difficult Situations, Total Picture Control, and How To Make Good Pictures — are stacked perfectly so as to become obelisks of aesthetic conformity. The presence of these sculptures suggests that anyone, with a little guidance, can master their own image. And so these sculptures also imply, at times with some redundancy, the betrayals, the benign hoax inherent in every image. On the third floor, two rooms are filled with contact sheets, all depicting the same whirl of pigeons starkly in flight above rooftops, against a lacteal sky; more migration, more Kodak-rendered abeyance. The oppressive sameness of each framed sheet is replaced by a curiosity for what is changed. Leonard’s insistence on seeing, unseeing, and re-seeing suggests that a photograph is not only a confiscation of experience, but also a political, emotional and unknowable holography. What information it conveys depends on the place where you are. In the Wake, in all its mere-ness, profoundly documents the way in which life itself is documented, and in turn, relives the quiet emergencies of seeing.