My cats were the first to notice that something was seriously wrong. Eyes wide and bodies tense, they were staring at the window that overlooks a narrow walkway by my apartment, straining to see whatever had tripped their silent alarms. They were ready.

I was not. I was half horizontal on my couch, exhausted and worried. My wife and I are academics and our daughter’s daycare is closing. How are we going to move our classes online and take care of her all day? Our families are far away; our friends are hunkered down in their own apartments. How will we manage alone? Deciding to block out the world and our problems for the evening, we were watching a ridiculous Italian crime drama, Non Uccidere. (Translation: “Thou Shalt Not Kill.”)

I muted the TV. Someone outside was bumping into the plastic trash bins.

This wasn’t itself alarming. I live in Los Angeles, in a big craftsmen house that has been divided into apartments and rented to the kind of polite young urbanites who are too busy to invite each other over for dinner but will say hello if they’re bringing out their trash at the same time. Every Sunday night homeless people roll shopping carts up and down the streets, rummaging through the recycling bins for our wine and beer bottles.

But this was Saturday night, and I didn’t hear the telltale tinkle of glass-on-glass. Plus this guy was talking to himself, louder than he needed to and slurring his words.

“Don’t look at me now,” he said.

He emphasized now, as if usually it would be okay to look at him, but not now. Look at him now, and you’re in trouble.

I heard his footsteps go across the patio, and then up the front steps to the porch.

Through the frosted-glass on my front door I could see his shape, a dark swaying figure under the porch light.

“Don’t look at me now.”

He turned and walked unsteadily toward my door, which I realized was totally unlocked. His shape blocked out the light in the window. I was nauseous and could feel my heartbeat fluttering like a bird in my stomach.

He stopped and turned to look through our dining room windows.

He couldn’t see us from where he was standing, and I couldn’t see more than his dark outline, but he was definitely staring straight into our apartment. Staring for what felt like a long time.

I live in a city of millions but have never felt more isolated. No one was coming to help.

He turned around and went back down the stairs.

I ran to the door and locked the deadbolt. I edged into the dining room and pushed the blinds closed. Peeking out I saw him from behind as he talked to someone over the front fence. He was enormous. Six-foot-five and at least 300 pounds. He had a shaved head.

I went back to the couch and (believe it or not) thought about Michel de Montaigne. He survived plagues and brigands and then, being Montaigne, thought long and hard about how to act in dangerous situations. Faced with someone who might hurt you, you have two options: beg for mercy or defy them. Beg, and they may pity you. They also might feel contempt, impunity, and kill you. Fight back, and they might be surprised, scared, or even respect you. Or they might get even angrier, and kill you. Unfortunately, it’s impossible to know ahead of time what the right call will be. You have to guess.*

This is ridiculous, I told myself. He’ll probably just go away.

He walked back up the stairs. His frame filled the window again and he said more loudly than before, “Don’t look at me now!”

He hit one of the dining room windows.

It made a high-pitched, rattling wail but didn’t crack.

“DON’T LOOK—” he hit the window again.

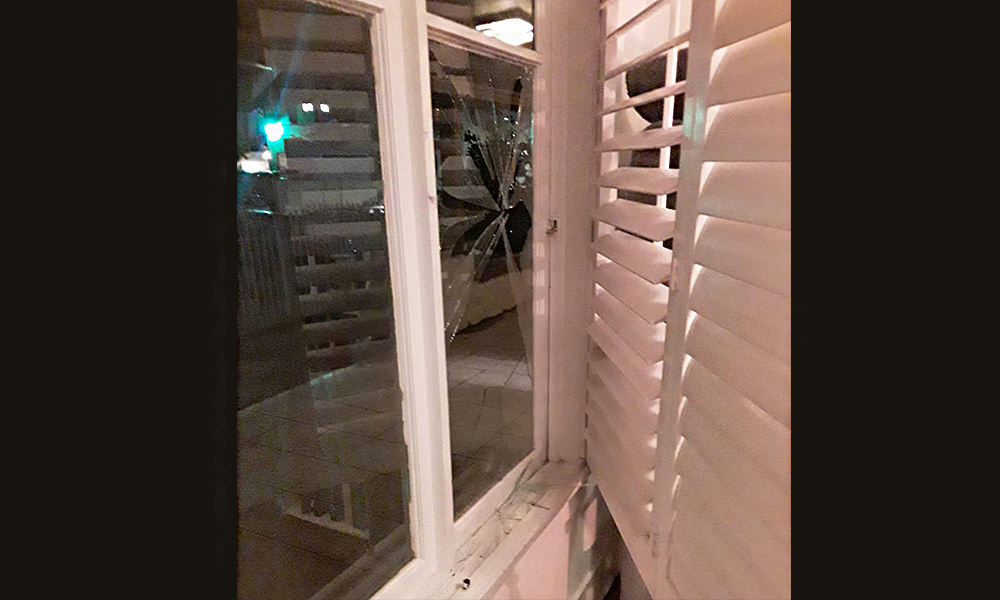

This time it shattered.

My wife screamed. My cats fled. I jumped off the couch and took two steps forward and shouted as loudly as I could, “GET THE FUCK AWAY FROM HERE!”

I listened.

Nothing.

There was broken glass all over the floor, but when I looked out the window he was gone.

I called 911 and stepped outside to wait for the police. On top of everything else, I thought, now this. The virus is swirling around the city, and just when I’m supposed to be sheltering in my apartment there’s a huge hole in the side of it. So much for staying inside and staying safe.

While I was waiting, my upstairs neighbor Chris came down to walk a friend to her car. “How ya doing?” he asked.

I told him.

He looked stricken and promised to be right back to help me board up the window. I felt a little guilty. I know he’s handy because I can always hear him upstairs hammering something or running his electric drill. Doesn’t he know he has neighbors? I’d ask myself.

Chris produced a sheet of plywood, sawed it into shape, and nailed it to my window frame. He gave me a sheet of plastic to put up inside to keep the weather out. When I tried to thank him he said, “That’s what neighbors are for, right?”

I agreed. Los Angeles can feel like a grand experiment in social distancing. Its deliberate sprawl allows us to keep our distance from one another, or at least pretend to. My dream of self-isolation, however, had turned out to be one more illusion in a city famous for them. I wasn’t as protected from the world outside my door as I liked to think.

But I also wasn’t alone. The “social distancing” and “shelter in place” orders have had the ironic effect of reminding me how close I am to my neighbors, and how completely we share one another’s fates. At the moment I was being told to keep my distance from everyone, I had relearned the value of having someone nearby.

In the days that followed I talked to my neighbors more frequently than ever before. From a safe distance we commiserated and exchanged numbers and each offered to pick up anything the other needed from the grocery store. It probably isn’t a great idea to buy milk and eggs for one another, but that isn’t the point. The offer itself sends a message: You’re not really alone. Help is right next door.

* This dilemma shows up at lot in Montaigne. You can find it right in the first chapter of his Essays: “That Men by Various Ways Arrive at the Same End.” Sarah Bakewell summarizes Montaigne’s view in How to Live (2010), pages 174-78.