It is a truth universally unacknowledged that American playwright Arthur Miller adapted Pride and Prejudice in 1945.

In the Theatre Guild Archive of the Harry Ransom Center in Austin, Texas survives a script, marked “as broadcast,” of Miller’s adaptation of Jane Austen for radio. Miller’s radio play, with Joan Fontaine as Elizabeth Bennet, aired on Thanksgiving eve, 18 November 1945. That celebratory Sunday was the first American Thanksgiving held in the wake of World War II, warranting special programming. In New York, Miller’s version of Austen could be heard at 10 p.m. on ABC station WJZ. The show made the list of “Today’s Leading Events” in The New York Times and was the Theater Guild’s most highly rated program that quarter, capturing a 19.4 percent share of the national radio audience. Today, Miller’s role as popular adapter of Austen has been all but forgotten.

The Janeite mind reels at the mere idea of young Arthur Miller being tasked to condense Pride and Prejudice to an hour-long format for radio. How could this American playwright, then honing his special brand of tragic realism that would challenge post-war complacency and eventually tilt at the windmills of McCarthyism, possibly give voice to Austen’s light, bright, and sparkling novel? The would-be king of American grit taking a crack at that quiet paragon of Britishness? Surely not. I dismissed the idea as ludicrous when a curator, knowing of my research interest in Jane Austen, casually mentioned the script’s existence. With zero pretentions at scholarly objectivity, I ventured into the archives to read the inevitable travesty for myself.

To my great surprise, I chuckled all the way through the script, disturbing other readers in the sanctum sanctorum of the Harry Ransom Center reading room with my unladylike snorts. That evening I downloaded a recording of the program from a site for dedicated radio buffs and listened to the performance as it had aired in 1945 (only the inserts from sponsors, preserved in the typescript, were absent from the recording). Although the clipped mid-Atlantic accents of the actors and the rapid-fire pace of their dialogue sounded artificial in the mouths of characters whom I knew from Austen’s pages, I was rapt. This deviant script dared to differ from Austen’s established adaptations. Unapologetically American, the language was irreverent and surprisingly modern.

Figure 2: Cover of program of Theatre Guild’s On the Air broadcast of Pride and Prejudice in 1945. Theatre Guild Archive (folder R136), Harry Ransom Center.

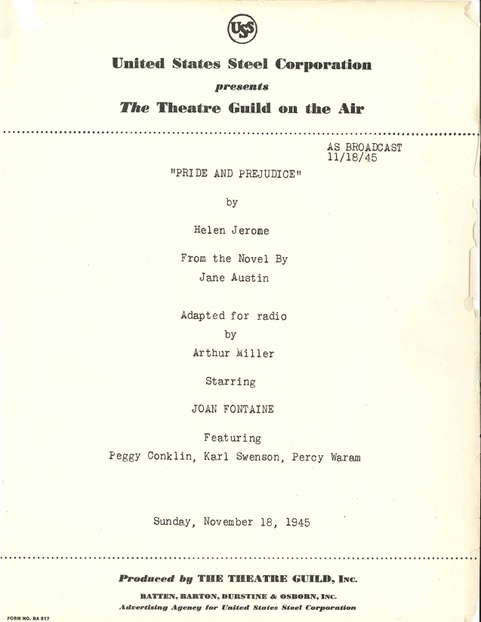

Sponsored on ABC by the United States Steel Corporation, the Theatre Guild’s “On the Air” Thanksgiving program began on 18 November 1945 with this announcement: “Tonight’s star is Joan Fontaine in Helen Jerome’s ‘Pride and Prejudice,’ taken from the famous novel by Jane Austen.” In other words, on the air Jerome received full adaptation credit, with top billing to Fontaine, star of the film Rebecca (1940). Published in 1935, Jerome’s stage version of Austen had been a Broadway hit that led to the famous 1940 MGM film of Pride and Prejudice — the one with Greer Garson and Laurence Olivier. In 1945, young Arthur Miller was acknowledged in the printed program and script but did not get on-air credit, so listeners must have assumed they were hearing pure Jerome. This is unsurprising since 30-year-old Miller had yet to make it big as a playwright (his first stage success would come with All My Sons in 1947). Miller’s task was that of respectable jobbing work to pay the rent, and I expected to see him lop and crop Jerome’s play with dutiful efficiency. To my surprise, I found a great deal of Miller in the radio script. And the broad comedy of it altered my dominant stance towards both Miller and Austen.

With a brief opening description (“a well-behaved house in a well-behaved England of a hundred years ago”), Miller wipes clean the slate of Jerome’s cluttered stage directions about furniture and wall hangings, sketching the scene with reference only to scent: “The only singular fact to record was the scent that hovered in the rooms. It was made of old lavender and lilac water — or whatever it is in the air that tells of many women in a house.” Was this Miller light? Regardless, there is nothing here of either Austen or Jerome, who do not ask their audiences to imagine sniffing Longbourn.

Figure 3: Cover of “as broadcast” typescript of Arthur Miller’s adaptation of Pride and Prejudice in 1945. Theatre Guild Archive (folder R136), Harry Ransom Center.

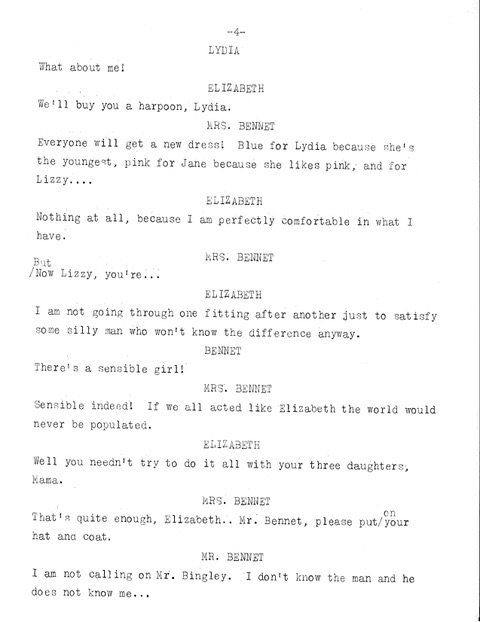

What follows are short comic bits between Mr. Bennet, Mrs. Bennet, and their three daughters (Mary and Kitty had ceased to exist in Jerome’s play and Miller kills off even more characters). In the opening minutes, Miller’s Elizabeth, promoted by him to eldest daughter, spars with her father about reading a novel that mentions divorce and resists his metaphor of a horse auction for the marriage market (“A man will pay for a horse,” quips Elizabeth). When Mrs. Bennet announces the arrival of Mr. Bingley, Elizabeth anticipates his marital status with an American idiom: “Why, Mama, anytime you run into a room like this, I know a single man has crossed the county line.” While there are indeed counties in England, this line, even when delivered on-air by Fontaine with the neutrality of a mid-Atlantic accent, stands out as un-Austen and ultra-American. When a delighted Jane generously suggests, “We must buy Elizabeth a new dress!” and Lydia predictably adds, “What about me!”, Elizabeth answers: “We’ll buy you a harpoon, Lydia.” And with that line, I was hooked.

Figure 4: Page 4 of typescript of Miller’s adaptation. Theatre Guild Archive (folder R136), Harry Ransom Center.

After taking away all agency from Mr. Bennet, who is pushed out the door with his gloves, hat, and coat by his daughters and wife so that he may meet with Mr. Bingley, Miller next transforms his Elizabeth into Scarlett O’Hara. With Elizabeth holding her breath as Jane laces her into a historically anachronistic Victorian corset unknown to Austen’s era, the radio play riffs on the famous lace-up scene from the 1939 film of Gone with the Wind. Elizabeth comments: “My spine seems to be in front. What idiotic things these corsets are. Everything from the middle is on top.” Jane answers, “But a girl cannot very well do without them, Liz.” Miller’s modern “Liz” refuses to yield: “If the Lord meant us to look like this we’d have our ribs running up and down instead of sideways.”

Joan Fontaine’s sweet and po-faced delivery probably saves this strange Elizabeth from becoming a wisecracking shrew, but if so it remains a close call. When Jane muses, “Lizzy you are so clever and so very pretty, and Mr. Darcy is really the handsomest man…”, Elizabeth cuts, “Snobs usually are. If he held his neck any stiffer a good breeze would crack it.” Similarly, when Jane becomes ill with heartache and Mr. Bennet forgets Bingley’s surname, the cultural familiarity with Austen’s original risks contempt as Miller dials up a comedy of manners to Dickensian absurdity in order to suit a radio format: “Is she still pining away for that Mr. Bungle or Bingle or whoever he is.”

The flirtatious Lydia Bennet is perhaps the best-preserved character, although even her comic moments are made broader by Miller than in either Jerome or Austen. The radio equivalent of stage descriptions, which mention “gentlemen in their tight trousers” dancing with “ladies in bustles and lace,” reinforce the low humor of Lydia’s speech: “How I’d love to see that Bingley in uniform! I imagine him with a broad red stripe down the side of his pants!” Mrs. Bennet’s curbing of her youngest daughter comically misses the mark: “The nice word is trousers, Lydia.”

At the ball, the flirting of Lydia with Wickham echoes Little Red Riding Hood confronting the big bad wolf:

LYDIA

“What lovely medals you have, Captain Wickham.”

WICKHAM

“Those are buttons, Miss Lydia.”

LYDIA

“Might I touch one? I know I oughtn’t but….”

Soon, Wickham invites her to step outside: “Come into the garden, Lydia, I’ll tell you all about Mr. Darcy.” Lydia hesitates, “I know I shouldn’t.” Her companion bites back, “But you know you will.”

None of this amounts to stellar writing or captures the tone of Austen’s original, but it serves as an efficient, if cartoonish, distillation of her plot for radio. In 1945, the Thanksgiving audience of the radio play expects comedy and already knows the famous story, likely through the vehicle of the popular film. With his tongue repeatedly if not firmly in his cheek, Miller offers a quick and dirty modernization into an American idiom rather than a short version of Jerome’s faithful play. This is not an homage to Austen (nor it is very respectful towards Jerome) but just a bit of sport with a classic story — popular holiday entertainment that anticipates the playful mood of Pride and Prejudice and Zombies. That this frothy amuse bouche at a Thanksgiving feast is written by, of all people, Arthur Miller is what remains, to me, so uncanny.

Why has this bizarre Miller-Austen mashup been ignored or disremembered? Biographers of Arthur Miller mention his early work for the radio industry, noting that it involved adapting plays by others (by 1945, Miller was earning a respectable $375 per script for this piecework). Since there is nothing like a profit motive to throw shade on art, such projects do not tend to be deeply scrutinized as part of Miller’s creative output. His Pride and Prejudice gets the briefest of mentions in the Critical Companion to Arthur Miller nodding to his comic approach (“several jokes”). Perhaps Millerites will therefore shrug at my naïve thinking that this is revelatory. But it is! Scholars of Jane Austen have focused on the popularity of Jerome’s stage production and its Broadway and film legacy, never realizing that a radio play which gave Jerome the on-air credit was actually written by the Arthur Miller.

Discoveries do occasionally hide in plain sight in archives and libraries. The Ransom Center’s “as broadcast” script is part of a Theatre Guild Archive that has been accessible to researchers for years (although some materials remain uncatalogued). The Ransom Center’s copy of the script is also not the only survivor. Author-centric academic specialties, combined with the hermetic isolation of the literary brands of Miller and Austen, led to this flawed gem of a work being overlooked. Perhaps now that this adaptation is in the open, scholars on both sides can consider the potential influence of Austen on Miller as well as Miller’s interventions in Austen’s reception history. Does the Lydia of All My Sons resonate with her Austen namesake? Was Austen’s popular reputation in America altered on that fateful Thanksgiving in 1945?

A high-profile oversight in an existing archive also gives hope of further discoveries. As it happens, the official Arthur Miller Papers, acquired two years ago by the Ransom Center, opened to researchers on November 13, 2019, making Miller’s personal papers available for the first time. The new archive includes his own copy of the Pride and Prejudice script, marked “3RD REVISED” and containing yet another round of annotations and revisions in his hand. This means that the delicious travesty that is Arthur Miller’s Pride and Prejudice was a considered effort that involved at least four rounds of dedicated revision. If Miller paid that much attention to his Austen project, perhaps so should we.

To that end, and with the help of Hidden Room Theatre, I hope to cheer on a revival of the radio play in 2020 for the 75th anniversary of its 1945 airing. Janeites and Millerites stay tuned.

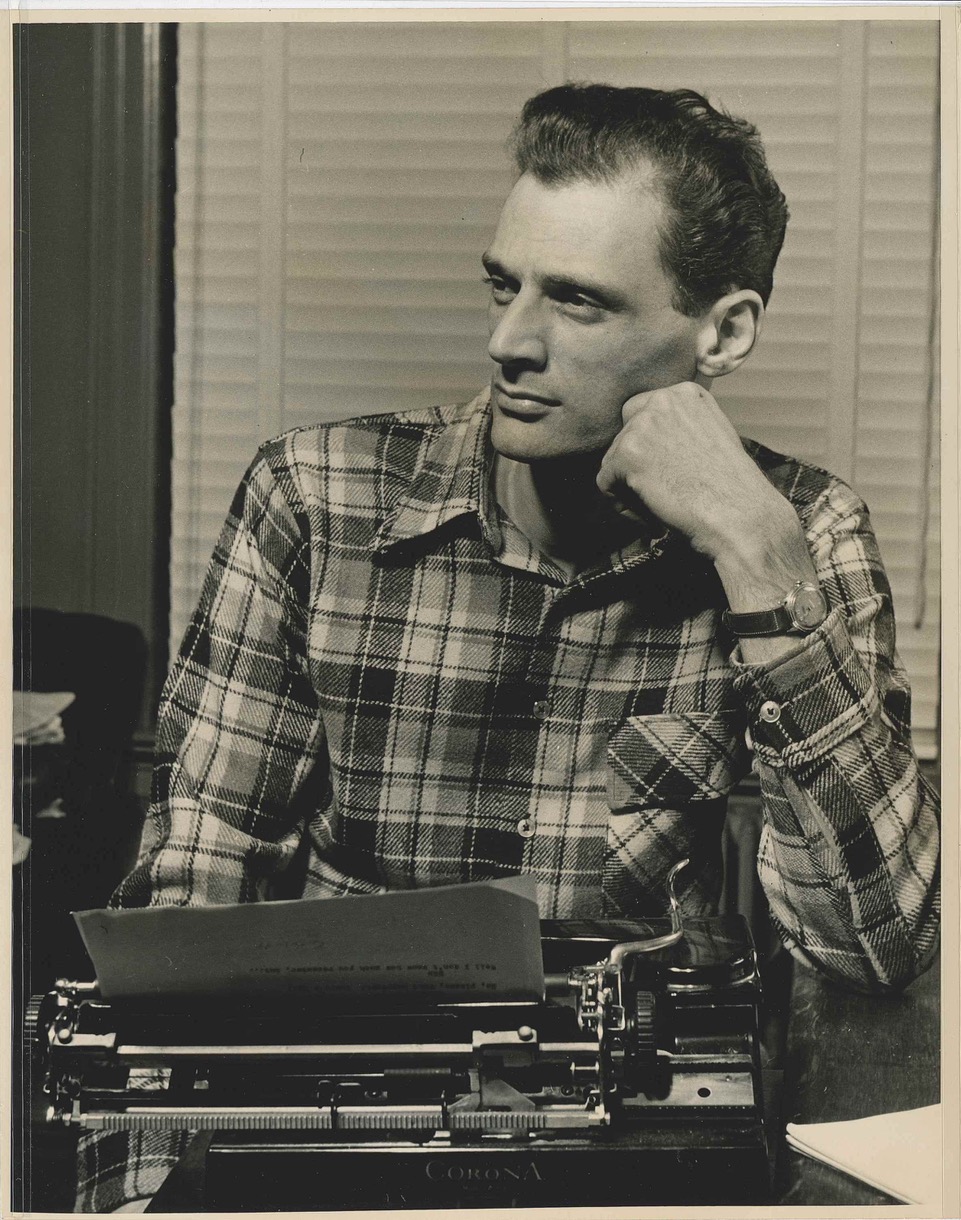

Figure 1 (banner image, above): Photograph of Arthur Miller by Esther Handler, circa 1945-1953. Courtesy Harry Ransom Center, Austin, Texas.

Janine Barchas is the Louann and Larry Temple Centennial Professor in English Literature at the University of Texas at Austin. Her “Austen in Austin” exhibition at the Harry Ransom Center runs through 5 January 2020. Her latest book is The Lost Books of Jane Austen.