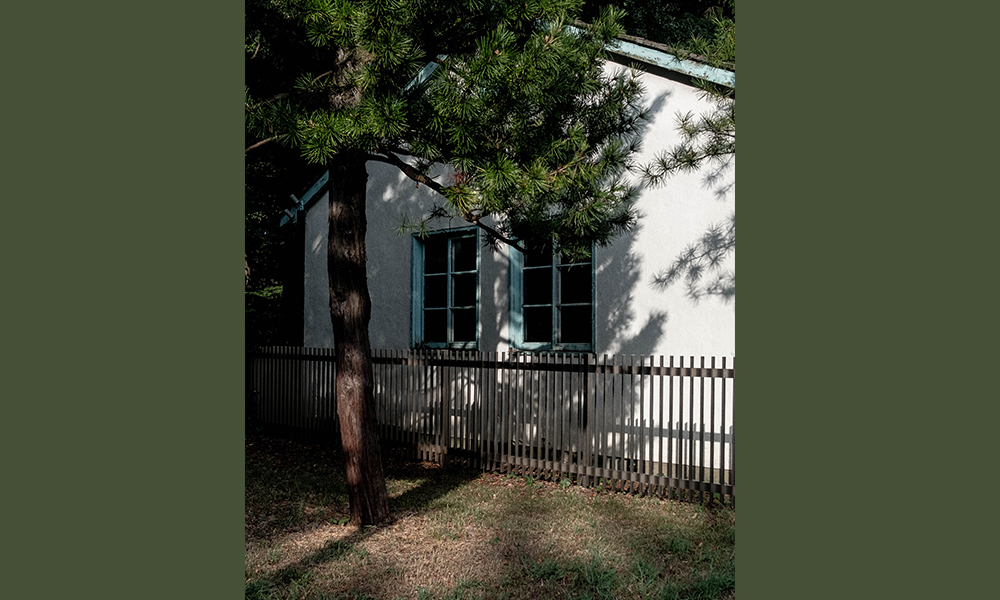

The house at the end of the path was white and old. Its windows were black with blue trimmings, and the trees, hefty and tall, towered behind. There was nothing special or distinguished about this house in a park surrounded by buildings and roads and highways. I thought it was a shed, maybe a decrepit structure, which recalled nothing in particular and meant nothing at all. To learn that this house was the only vestige of the 1964 Olympic Village was to uncover a past both hidden and obvious.

The house, once home to the Dutch team, beckoned to the past with its walls and windows and a small sign that read: “Olympic Memorial House.” A metal fence, which was newer than the house, cordoned it off as if it were a museum object. It was old, and branches traced the walls. The house recalled the 1964 games, which were Tokyo’s first Olympics (the 1940 games were canceled on account of war) and held the promise of a future that was bright and mighty. After the games, the bubble had burst in 1991, and was followed by economic stagnation that has never really relented. But the 1964 games were the apex, the height of the postwar — before it all went wrong. The hopeful past signaled by the Olympics was now lost and set aside, sequestered, as a crumbling ruin, to a corner of Yoyogi Park.

In the early 2000s, Tokyo hoped to hold the Olympics again, and the past that seemed lost was to be reclaimed and recalled. Shunya Yoshimi, a professor at The University of Tokyo, wrote, “In the mood of stagnation of Heisei (1989–2019), people tried to give rise to ‘that glorious era’ with another showing of the Tokyo Olympics.” A second Tokyo Olympics would be the reincarnation of the 1964 games and herald an end to the unyielding “lost decade(s)” of the 1990s and 2000s.

Tokyo applied to host the 2016 games, and was selected by the IOC as one of four candidate cities, but, in 2009, lost to Rio. The 2020 Tokyo bid, sent to the IOC in 2013, emphasized the legacy of the 1964 games and the existing Olympic venues as a ready-made foundation. But it also offered a more immediate promise: the Olympics would be a games of reconstruction, a beacon of hope in the aftermath of the 3/11 disaster (the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami). Though the story helped Tokyo to secure the bid, the loftier promise remained: a return to the glory of the 1964 games and revival of economic prosperity. The day that the IOC awarded Tokyo the games, then Prime Minister Shinzo Abe announced, “I want to make the Olympics a trigger for sweeping away 15 years of deflation and economic decline.”

And so, in Tokyo, everything seemed to look towards the games. When I returned in 2018, after a year away, I found a city that swelled with hope and anticipation. At first, the hints were subtle and banal. New taxis, large and black, had the Olympic and Paralympic logos affixed to the sides. A driver said that they were built to accommodate “bigger-bodied foreigners” (this is unverified, but I enjoyed the extra legroom). Posters of the Olympic and Paralympic mascots, Miraitowa and Someity, covered the walls of metro stations. Olympic paraphernalia stocked the shelves of stores. The countdown clock was placed next to Tokyo Station, adjacent to the Imperial Palace. On July 24, 2019, the clock began to tick: one year to the games.

Once a week, on a mad dash to a class, I took the Ginza Line to Shibuya, a tourist hub that also sat adjacent to the Olympics venues built for the 1964 games. For the 2020 games, the venues were to be reused, and Shibuya would be a key center for visitors — an already crowded area soon to be overcome by even more people. The train would turn and rumble, and the announcer would announce that the final stop, Shibuya, was approaching. The Ginza Line’s doors would open, and crowds would rush onto a platform that was too small and cramp. The tiled floor was old and yellowed, and the walls were padded and entrances haphazard. The ticker gate took you to other parts of the stations, some newer, others older, and many with views of construction on the streets.

But Shibuya was changing. I remember a video — on subway lines some years ago — that portrayed a time-lapse where buildings grew, and the neighborhood’s skyline became crowded and grand. There was no mistaking: the area was preparing for the Olympics. At the end of 2019, the skyline was punctuated by cranes and the streets with barriers for construction. For 10 years, a new terminal for the Ginza Line was underway, which opened in January of 2020 as the games moved closer. Now, the doors of the Ginza Line opened onto a sprawling terminal, with an M-shaped roof and wider platform. The new terminal connected to Shibuya Scramble Square, which had opened two months earlier and had 47 floors. The bottom levels were stores, and above were offices. And there was a rooftop platform, which towered above the city, and when you reached the top you were surrounded by glass walls.

From that roof, the city, with crowds and people and buildings, looms below. The city, an Olympic city, is sprawling and grand, and the cityscape is flat but expansive, gray but vibrant. The National Stadium, designed by Kengo Kuma as the main stadium for the Olympic games, melds into the cityscape below. Here, the opening and closing ceremonies and other events of the 2020 games were to be staged. The stadium was completed in December 2019, in place of the first National Stadium built for the 1964 games. Both stadiums displaced people who lived in the area. But that didn’t matter to the organizers. It was to be the symbol of the games, and so a symbol of Japan.

From the roof in Shibuya, you see another roof that twists and turns and foregrounds a mess of trees. It is the roof to Kenzō Tange’s Yoyogi National Gymnasium, the venue that will soon host the Olympic and Paralympic events of handball, badminton, and wheelchair rugby. Nikil Saval has called the gymnasium, which was built for the 1964 games in Yoyogi Park, “the most breathtaking example of Japanese Modernism.” Christian Tagsold — a scholar of Japan, who has done extensive work on the 1964 games — has found a latent connection to Japan’s imperial past in the gymnasium’s location, which speaks to a promise of patriotic revival in the 1964 games. But he has argued that the 2020 games, which will reuse the gymnasium, “do not promise anything fundamentally new.”

Come 2020, when the games were set to open, the COVID-19 pandemic hit and the games were deferred and the countdown clock at the foot of Tokyo Station was unceremoniously reset. Japan closed its borders and foreigners were ostracized and criticized. Tokyo 2020 became Tokyo 2021, though the name was never changed. So determined and driven were officials that they now offered a new promise: “The Olympic flame can really become the light at the end of this dark tunnel the whole world is going through together at this moment,” said Thomas Bach, the IOC president; but, the promise was empty.

The pandemic continues to rage, and the Olympics and Paralympics will be held without foreign spectators, if not canceled altogether. Satoru Arai, head of the Tokyo Medical Association, which is to supply medical staff to the games, recently told Reuters, “No matter how I look at it, it’s impossible.” Doctors, he continued, could not leave their hospitals — pummeled by COVID, short on beds — to aid the games. In a recent survey, 80% of people in Japan thought the games “should be canceled or postponed again.” Yoshiro Mori, president of Japan’s Olympic organizing committee, soon said, “The biggest problem is public opinion.” Days later, he would joke that women in a board meeting talked too much. He soon stepped down.

Tokyo 2020 has revived an old promise. A complex legacy is at stake and, if the Olympics are canceled, the nearly reclaimed past — of the 1964 games, of the postwar, of economic growth — will be lost. “After a long night, there will definitely be a morning,” pronounced Mori. The night is our present, a time of COVID and despair, but it is also the economic decline, the time after the Olympics. In one of the final sequences of “Tokyo Olympiad,” the film of the 1964 games, Kon Ichikawa also laments night, for but a quote adorns the screen to the backdrop of the Olympic flame:

Night,

And the fire returns to the sun;

for humans dream thus once only in four years.

Is it then enough for us —

This infrequent, created peace?

And so, there was a night, which arose after the games and darkened in 1991.

If the games are canceled, the financial losses will be great. The dreams of athletes will be dashed. But so, too, will the losses be symbolic. New stadiums will sit empty and silent, and grand renovated stations will sit unused by tourists. The city, which planned and prepared and hoped, will be without the games. And the promises of the games, which have been building for years, will be lost yet again.

And that white house, in Yoyogi Park. It has another story that is hidden and unsaid: it was first built to house American military families when Yoyogi was not a park, but an American military base called Washington Heights. “Rather, many of the competition venues that became stages for the Olympic spectacle when the games finally came to Tokyo in 1964,” wrote Yoshimi, “were postwar products, built on the sites of former military facilities.” The 1964 Olympics hid a past, an era of American occupation, which never really ended.

That white house still stands and symbolizes a past, lost and hopeful. It bears traces of occupation. But that is forgotten now, sequestered in a corner of the park, overshadowed by Tange’s gymnasium and, come spring, the cherry blossoms.