To see the first-ever art exhibit at the National September 11 Memorial & Museum, you must first descend the escalator, walk past the spotlit wreckage displayed as part of the museum’s permanent collection, past armed guards, past fire trucks warped beyond recognition, and, finally, past the buckled I-beams and other debris that haunt Ground Zero. These artifacts serve as totems of perseverance and frangibility, souvenirs of past atrocity. Yet this preceding layout is such that, once you enter the gallery, the art feels unnecessary, perhaps even insensitive. What can creativity achieve amid so much pain and loss? In light of this duality, both the helpfulness and helplessness of art are on display in Rendering the Unthinkable: 13 Artists Respond to 9/11, an exhibit that embodies the comforting generalities that annex America’s remembrance of 9/11 today.

The artists in Rendering the Unthinkable can be seen as spiritual indemnifiers, tasked with culling significance from revisitation. Some artworks masquerade as evidence: singed pieces of paper turned into leaves; a pair of abstract canvases impastoed with “World Trade Center Ash”; a matrix of acrylic portraits borrowed from media coverage. But when any teenager with internet access can watch footage of the attacks, it is unlikely that these interpretations will substantially shape the younger generation’s perception of the early 21st century. The instinct to return to the zone of disaster — to think the unthinkable — is an invincible one, but the inexorability of spectatorship does not excuse the limited emotional and moral orbit in which so many 9/11 artworks exist. Rather than helping us understand how the contours of American identity have or have not been remapped, these New York artists have instead chosen to alibi a moment that is in no realistic danger of being unbelieved.

Art’s role in reacting to inhumanity can be anxiety-producing, as both artist and viewer confront the difficult subject matter in its reimagined form. One way to bypass the fear of exploitation is to root the work in fact, in archival material — to combat creation with restaging. In a 2011 essay titled “Outdone by Reality,” New York Times critic Michiko Kakutani condemned this approach, arguing that visual artists failed to reflect on the World Trade Center attacks with the same emotional and moral fluency as the mainstream media, whose straightforward documentation provided a more helpful narrative. “How does one convey the enormity of the event without trivializing it?” Kakutani wrote. “How does one bend art forms more often used for entertainment or artistic expression toward the capturing of history?” But by obliging artists to assume the role of instructive historians, Kakutani elides art’s ability to rethink the way cultural and political crisis is framed — a difficult but worthy task.

Rendering the Unthinkable fails to challenge Kakutani’s premise, though it admirably refuses to construct a facade of political or personal closure, instead planting us in the midst of 9/11 and its immediate aftermath. In its attempt to reimagine unfathomable brutality and to tether us to “what was lost,” the project allows few competing visions (a firmer embrace of younger or international participants may have helped this) and strives instead for a tender catharsis that evades the artistic provocations we rely on to organize the complexities of the world.

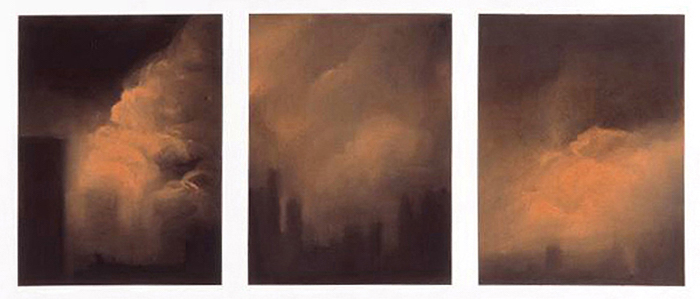

Only six days after the catastrophe, composer Karlheinz Stockhausen remarked, in a display of cosmic insensitivity that earned him lifelong ignominy, that 9/11 was the “greatest work of art that is possible.” But even if the backlash to the ineptitude and selfishness of Stockhausen’s claim crystallized the consensus that 9/11 itself could in no circumstance be considered art, we must still contend with the many critics and art consumers judging 9/11 art — if such a genre exists — against the actual event. That so many works included in Rendering the Unthinkable aestheticize atrocity indicates art’s ability to laminate tragedy in beauty, despite any discomfort that may cause. “Beauty brings copies of itself into being,” Elaine Scarry wrote in On Beauty and Being Just, but horror, too, impels imitation. The ambivalence experienced while looking at some of these works — full of horror and beauty — is vertiginous, somehow both purgative and nostalgic.

“We saw no bodies,” Eric Fischl says in a behind-the-scenes video accompanying “Tumbling Woman,” a bronze, somewhat Hellenistic sculpture that saw much controversy in 2002 when it was displayed in Rockefeller Center, sparking debate about whether Fischl’s work should be seen in a public space so soon after 9/11. Fischl is both describing and refuting a surreal vanishment, an impossible invisibility within such a visible and violent catastrophe. The sculpture became an effigy after many accused the artist of exploiting those who had leapt to their deaths from the towers — an indictment that divulged a resistance toward art that embodied trauma and grief. Never forget is a political and personal slogan we have justly assembled under, but for many artists, remembering the September 11 attacks means remembering around them. Fischl confronts the facelessness of 9/11 art and urges visitors to interact with his sculpture on a visceral register, in a moral penumbra that other artists shy away from.

Whether “Tumbling Woman” is meant to personify America is left up to the viewer. On close inspection, her expression is illegible, the features half-formed. The musculature echoes the feminine form of Renaissance paintings, a decision that suggests a curious timelessness antithetical to a moment in history so intrinsically time-stamped. She resembles the victims of Pompeii, tableaux paralyzed in volcanic ash. By pausing a final act of defense and vulnerability, Fischl turns art into artifact, in an exhibit compelled to do the opposite.

In her video “daughter, sept. 13,” Colleen Mulrenan filmed herself washing her father’s shirt as he slept. The shirt, its pocket stitched with a police crest, belonged to an outfit sullied with ash and grime from Ground Zero, from where the deputy chief had returned home that night. In a bathroom sink, Mulrenan scrubs the white button-down so that it will be clean for him the next day, and it slowly brightens as the filth seeps into the sudsy water. Audio of machinery and radio static textures the footage with a haunting drudgery. The video can be read as an allusive act, a rinsing of America’s terrors, its memory, its dirt. But it resonates more as an intimate gesture of kindness juxtaposed with the heroism of civic duty.

In another area of the exhibit, aquarelles of boats marbled in Montauk sunlight and paintings of lace are offered as examples of imagery created not to necessarily memorialize 9/11, but to prod a specific wonder toward the dailiness that bloomed in post-9/11 America. Everyday experiences like admiring the touch of fabric or basking in daylight felt not only more precious, but more susceptible, finite. In this way, 9/11 art also enters the canon retroactively, as past images are reclaimed as vanitas. One thinks of Giorgio Morandi’s oil still-lifes of mundane objects: bottles, bowls, and carafes evoked in muffled, matte hues. These compositions are transfigured through subtext in Don DeLillo’s 2007 novel Falling Man, in which a character repeatedly sees those bottles and imagines the towers, their absence.

Soon after the destruction of the towers, art critics began to predict what new gravities the art world would move within. In New York magazine, Mark Stevens anticipated a seismic, if immeasurable, shift away from conceptualist decadence toward a more fact-based approach. In Newsweek, Peter Plagens deemed artists incapable of making “work profound enough to do justice to the horrors of this September,” but did not clarify what this justice might look like. Arthur C. Danto suggested that, in order to be truly genuine, 9/11 art must “find ways of embodying the feeling rather than depicting the event, [which] is inevitably oblique.” Danto went on to imply that perhaps some of the most meaningful 9/11 art is made without an umbilical attachment to 9/11 itself.

The primary sources used in the exhibit, as well as the evocations of the attacks themselves, signal a hesitancy to imagine anew in the wake of devastating terrorism. This reflex is something artists must resist, lest they ratify the cynical belief that 9/11 art, or even art in general, cannot contribute to or understand society as purposefully as “actual events” can. Fifteen autumns after 9/11, unutterable calamity has not only surpassed the realm of disbelief — it can occupy our every other thought.

“Nothing is more abstract than reality,” Morandi once said. Less than a day after visiting Rendering the Unthinkable, the neighborhood where I work started trending on social media — a pressure cooker had detonated in a trashcan on West 23rd Street. As this attack and its implications whorled in my mind, I remembered Mulrenan’s video, the plaintive compassion shadowing the fact that her father will wake up at dawn and put on the same white shirt. He will go back to work, return home, and go back the day after that. And the day after that, and the day after that.