France has a way of enticing Californian women who love to cook. I’m one of them — I spent a month in the Loire Valley working at an inn run by three older gay men. They taught me the slow, serene French way of life, one never without wine, where cheese is eaten and stored with reverence. They taught me to let my cheese breathe: “Respiration!”

The owner of the inn, Jonathan, an American ex-pat artist, was of the Berkeley counterculture generation, and was in Berkeley with Alice Waters pre-Chez Panisse. Waters has been my idol for years, so this fact especially piqued my interest. I thought a lot about Waters and her connection to France while at the inn. I also thought about Alice B. Toklas often, who lived and cooked in France during WWII. Waters named her restaurant after a character from French director Pangnol’s Marseille trilogy because she felt akin to the “earthy, … sentimental,” and romantic air in those films. Toklas held court in that way of life.

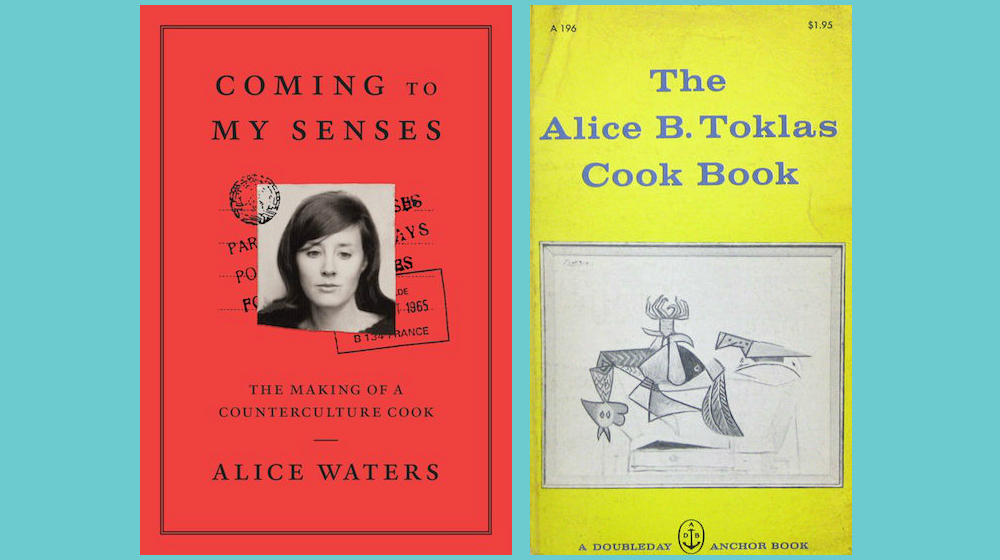

Both Alices wrote autobiographical accounts of their lives and connection to France and food — The Alice B. Toklas Cook Book and Coming to My Senses: The Making of a Counterculture Cook. Each book shares the story of the respective Alices life, how she came to France and discovered a connection to the sensual lifestyle there. Both stories lovingly describe how cooking in the French tradition with a French mentality helped them forge a path of hope through times of civil instability.

Toklas is known mostly as being the muse, or “secretary-companion,” to Gertrude Stein. But her “Cook Book” sheds light on what her life was like alongside the genius. She cooked and gathered artists, writers, and filmmakers around a communal table. She collected recipes from her friends and even dedicated a whole chapter in her book to these recipes — “Recipes from Friends.”

More than these social dinner parties and histories of famous friends, what is gleaned from Alice’s food-laced recollections is that food was a source of optimism during times of fear. Recipes themselves were a welcomed distraction during the long winters of the Occupation. Toklas took to “the passionate reading of elaborate recipes” which allowed her to forget about governmental restrictions on food. The women lived in the French countryside during the war, and at one point were enlisted to host German soldiers. Shortly after the description of this incident in the cook book, in which a Jewish lesbian couple had Nazis sleeping in their house, a recipe appears for “Liberation Fruit Cake.” One can imagine Toklas dreaming up the recipe sleeplessly while a Nazi soldier dozes in her spare room.Toklas saved dried fruit in jars for the day of the liberation: “The jars of candied fruit were […] a symbol of happier days soon to come.” When those days finally came and the cake was made, it was a physical and gustatory manifestation of hope. The act of making a cake to celebrate the end of the war was political in its own right. It meant not only celebrating the end of the war, but the return to cooking in the way the French did: with butter! Some ingredients had to be bought off the black market, but the two women also had a garden that sustained them during the war and for many years. Harvesting in the garden made Toklas feel like “a mother about her baby.” Nothing could compare to the feeling of “gathering the vegetables one has grown.”

Toklas never explicitly states her sexual orientation in her memoir, but she writes about living and traveling with Stein openly — a revolutionary act even for 1954, when the book was first published. Both Toklas and Waters fed the resistances of their generations, not as housewives, but as women who were inspired to cook. Waters states that it was because of the counterculture that she could “run [her] kitchen as [she] wanted, and do so as a woman” which was rare at that point. The Alices were the start of a culture of women cooking to nourish and create, not because it was their specified gender role.

Like Toklas, Waters was enthused about her grown food. Her cooking and gardening was explicitly political. Waters was an active participant in the Free Speech Movement in Berkeley — she was an active protestor and worked with radical journalist Bob Scheer on his campaign for congress. Scheer’s loss left Waters despondent: she “didn’t believe change could happen…[she] really lost hope.” This coincided with her return from a year abroad in France; she channeled her counterculture passion into sharing French food and culture with her community.

Waters had a newspaper column in The San Francisco Chronicle called “Alice’s Restaurant” where she emulated the awakening of taste that she experienced in France. She shared her own recipes and those of the people she loved. Sharing “the right food” was her form of activism. Her attitude toward feeding people was akin to her communal lifestyle. Like Toklas, she welcomed all into in her home and cooked for artists and writers who came by the house. It was these frequent visits and meals that inspired her to open a restaurant. In the afterword to her memoir, Waters writes that she “was deeply disillusioned about politics, and by opening the restaurant, [she]…thought [she] was dropping out…no politics, just [her] little place. But it became political. Because as it turns out, food is the most political thing in our lives.” Food’s political history started early for Waters, in her parents’ Victory garden. So when Chez Panisse finally opened, Waters saw food sourcing as another opportunity to forge a path away from the government and mainstream. She accepted produce from neighborhood regulars in the first years of the restaurant, an under-the-table operation that brought in Meyer lemons, French breakfast radishes, and special German potatoes. She saw produce as an opportunity to communicate a political and personal message. When then-President Bill Clinton dined at Chez Panisse, Waters wanted to give him the perfect peach at the end of his meal because taste is “deeper than language…it’s hard to connect with people if they can’t connect to their senses.”

I felt a kinship with Toklas and Waters during my time in France, cooking with produce from the garden, feeding friends, and sitting around the table drinking wine. The French treat a meal as a time to relax, celebrate, and be present. Those who observe the French culinary tradition treat it with devotion. Taste was the key sense for both Alices. Both women used taste as an escape from fear but also as a way to communicate hope. The sensuality of the French lifestyle became their mode of defiance — they chose to cook instead of wallow. Their gardens were places where things could grow even when things seemed destitute. Their kitchens were spaces where something good could be made, even if everything outside the kitchen door wasn’t.