The director Whit Stillman is beloved for his witty debut Metropolitan (1990), which focuses on a group of chatty Ivy League undergrads arguing about the meaning of life as they traverse a series of Manhattan debutante balls. Made on a shoestring budget, Metropolitan became a surprise arthouse hit after it premiered at Cannes, garnering Stillman an Academy Award nomination for Best Screenplay. Alongside Steven Soderbergh’s Sex, Lies, and Videotape (1989), it helped kickstart the indie movie scene of the 1990s and served as an inspiration for writer-directors like Noah Baumbach and Wes Anderson, who’d go on to emulate Stillman’s gently satirical style and his fondness for the eccentricities of a social milieu described by one character in Metropolitan as the “urban haute bourgeoisie” — UHB, for short.

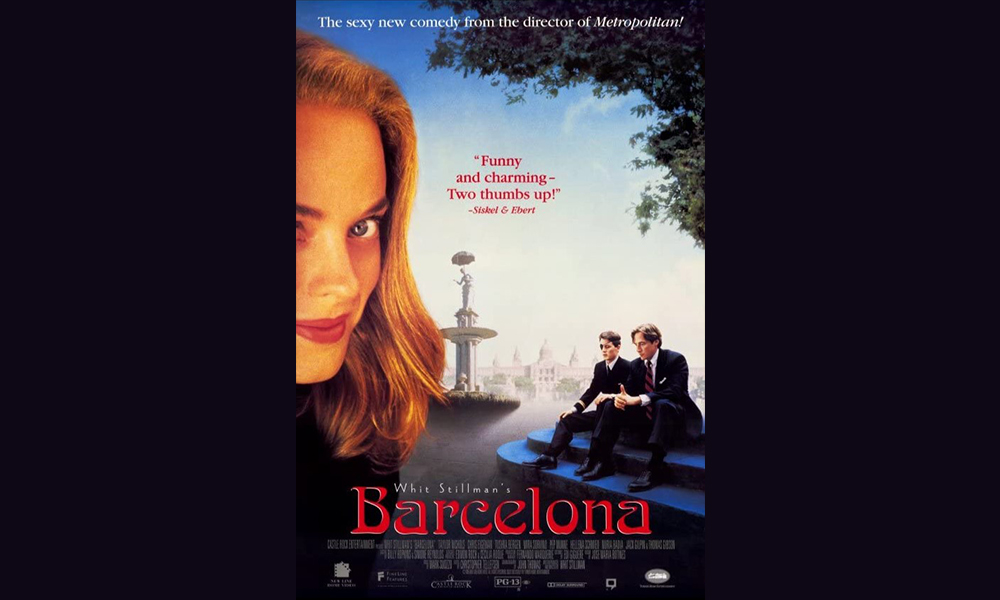

But for a cult indie director, Stillman has an unusually conservative worldview, something that’s more apparent in his lesser known second film, Barcelona (1994). The movie shares some DNA with the oblivious-Americans-abroad genre pioneered by Graham Greene’s The Quiet American, a genre in which the moral simplicity of naive Americans typically gets revealed as a front, conscious or otherwise, for the nation’s rapacious postwar imperialism. Only in Stillman’s recasting of the trope, the oblivious Americans are the heroes. Barcelona stages a Boomer fantasy of American empire, one in which the US and its values are essentially benevolent forces in the world. Not only is European anti-Americanism shown up as misplaced and misguided, but the snooty Europeans are compelled in the end to admit it. The film’s argument amounts to a revenge fantasy enacted via capitalism and hamburgers — an argument perfectly pitched for the triumphal atmosphere of the 1990s.

Barcelona focuses on two American cousins, Ted and Fred Boynton, who work and cohabitate in the Catalan capital while exploring the city’s “promiscuous” dating scene. It’s the 1980s — the “last decade of the Cold War,” as the historicizing opening credits announce — and Spain is enjoying a hedonistic rebirth, sloughing off its fascist past in the wake of Franco’s death in 1975. On their first night out together after Fred shows up unannounced at Ted’s door, Ted explains the situation to his cousin: “The sexual revolution reached Spain much later than the US, but went far beyond it…. Here in Barcelona, everything was swept aside. The world was turned upside down and stayed there.” As UHBs reared in the prep schools of Chicago, Ted and Fred find themselves alternatively flummoxed, intrigued, and repelled by the decadent world into which they’ve been thrust.

Fred, a Navy officer serving in Spain as “sort of an advance man for the Sixth Fleet,” responds to his confusion with jingoistic fervor. Throughout the movie, he insists on parading around in full military regalia despite receiving direct orders from his commanding officer to wear civilian clothes. (“Men wearing this uniform died ridding Europe of fascism,” he explains to Ted.) When Ted informs that him post-Franco Spain might not be receptive to a visit from the Navy fleet — “There’s a lot of anti-NATO feeling here” — Fred gets incensed. “They’re against [NATO]?” he asks, shocked. “What are they for? Soviet troops racing across Europe eating all the croissants?” Other slights that set Fred off include British accents, European jazz, and Spaniards who disapprove when he refers to himself as an American. “They love to correct you,” he complains on a date with a Barcelonan girl, “saying ‘South Americans are Americans too.’ I mean, give me a break!”

Ted has his own reactionary proclivities. Working as a salesman for the Illinois High-Speed Motor Corporation, Ted spends most of his time at the Barcelona Trade Fair ogling the attractive “Trade Fair girls.” This has prompted the development of a theory that beautiful women are a malevolent force in the world, and his resolution to date exclusively “plain, or even rather homely girls.” When he’s home alone, Ted has a habit of reading the Bible while putting on Glenn Miller records and dancing the Charleston. (“What is this?” Fred asks after stumbling upon Ted’s shameful secret. “Some strange, Glenn Miller-based religious ceremony?”) Before becoming a salesman, Ted had the UHB’s typical “sneering, deprecating attitude to the world of business,” until a charismatic college professor helped him recognize the “romance” of corporate America. Now he’s a devotee of Carnegie and Bettger. As he explains in a voiceover: “The classic literature of self-improvement really was improving.”

Stillman is a droll satirist, and his portrayal of the Boynton cousins is clearly intended to be a caricature. In any Stillman movie, bold arguments are something to be distrusted, and whenever a character states a strong opinion you can expect the story to deliver a swift comeuppance. Stillman plots are intricately constructed homages to 19th-century novels of manners (replete with aristocratic villains and dark-horse romantic interests that emerge in the third act), and he loves the Tolstoyan trick of letting dramatic irony do the work of gently undermining a character’s delusions. But Barcelona feels different in a critical way from Metropolitan or his 1998 film The Last Days of Disco (the third entry to his “doomed bourgeoise in love” trilogy). Despite poking fun at the cousins, the movie honors — and ultimately vouches for — the Boynton worldview. This is the gentle irony you reserve for a past self. The way you expressed yourself may have been laughable, but fundamentally you were on the right track.

It should come as no surprise that Stillman himself is a classic UHB. Uncharacteristically for an indie filmmaker, however, Stillman is a product of the East Coast political establishment. His father was John F. Kennedy’s Secretary of Commerce in the 1960s, and his great-grandfather was a legendary chairman of Citibank. At Harvard in the turbulent 1960s, Stillman found himself drawn to conservatism, something his friends describe in Freudian terms as a rebellion against his prominent Democrat father. After graduation, he began writing a column for the American Spectator, an intellectually rigorous conservative magazine whose circulation exploded in the 1990s when it launched a more populist-minded crusade against Bill Clinton. Although Stillman gave up his column years before becoming a filmmaker, a 1994 profile in New York Magazine claims that, around the time he made Barcelona, Stillman was still writing the occasional Spectator article under a pseudonym.

This background helps clarify Barcelona’s political subtext. Consider the movie’s indisputable villain, Ramon, an ex-boyfriend of one of the Trade Fair girls both Boyntons eventually date. Ramon writes for the style section of a Barcelona newspaper — his beat, he claims, is “female beauty” — and he specializes in profiles of Spanish models. The Boyntons clearly see this as a pretext for lechery; Ramon makes no secret of hoping to seduce the women he covers. He also has a penchant for politics, and occasionally writes investigative pieces about American imperialism. As Fred’s girlfriend Marta (another Trade Fair girl) explains: “Ramon [has] read the work of Philip Agee, so he [is] an expert on the American CIA and its involvement in the internal affairs of every country.”

Marta (played by Mira Sorvino) is the movie’s second major villain — a shallow conniver and a thief — and this line is underscored with the same arch irony as Fred’s comical jingoism. The fact that reading Agee is a subject of parody, however, is telling. The CIA did in fact involve itself in the “internal affairs of every country” during the Cold War, and Agee’s 1975 memoir, Inside the Company, is one of the most detailed renderings of its interventionist tactics available in the public record. Although Agee became a controversial figure after he started purposefully publicizing the names of CIA agents (which some argue led to the 1975 assassination of Richard Welch, a CIA station chief in Athens), even head honchos at the CIA admit that the book’s fundamental premise — that the CIA in the 1970s was manipulating politics across the globe at a minute level, from fixing elections to helping governments arrest and torture leftwing dissidents — is inarguable. It takes a particularly American brand of amnesia to find it laughable that a journalist in post-Franco Spain might be interested in America’s long history of covertly supporting fascist military regimes.

But Barcelona was produced in the 1990s during the much-heralded “End of History,” and Stillman’s political amnesia is far from an isolated case. Perhaps more noteworthy than the politics of a small indie film is the extent that Barcelona’s worldview was shared by mainstream cinema of the era. The 1990s were a decade defined by blockbusters like Patriot Games (1992), Executive Decision (1996), and Air Force One (1997) — movies that glorified the competence and imperial grandeur of America’s armed forces. Unsurprisingly, many of these productions received funding or supervision from the Pentagon, an arrangement critics have dubbed the “military-entertainment complex.” Stillman’s conservatism may have been unusual for an arthouse director, but within the nationalistic ranks of contemporary Hollywood, it was de rigueur. On the consumer side, meanwhile, 1990s tastes were being dictated by the Baby Boom generation, who grew up in an era of social and sexual revolt but ultimately bought in hook, line, and sinker to the Reagan Revolution. For conservative-leaning Boomers like the Boyntons, the denouement of the Cold War would go on to ratify the messianic way they envisioned America’s role as “leaders of the free world” — and anyone who thought otherwise, like Ramon, could be comfortably dismissed as a crank or a sore loser.

Barcelona’s ending perfectly encapsulates this outlook. Ted and Fred have brought their girlfriends back to the United States. (Ted eventually gives up on his quest to find a “homely” girl, but luckily manages to locate a pretty Trade Fair girl who’s excited about “the 80 channels of television and the abundance of consumer products in the US” — something Marta and Ramon disparage earlier in the film.) The four of them are now hanging out at the Boynton family lake house, enjoying some grilled hamburgers. Throughout the movie, Ted and Fred have argued with Spaniards about the virtues of the American hamburger. “[Europeans] have no idea how delicious hamburgers can be… it’s this ideal burger of memory we crave, not the disgusting burgers you get abroad.” Ensconced at their ancestral lake house, the Boyntons have a chance to prove they’ve been right all along.

Watched carefully by the cousins, Fred’s girlfriend gives the burger a try. For the first time in the movie, we witness an expression of enthusiasm that isn’t undermined by Stillman’s droll irony. “Incredible!” she exclaims.

“You see,” Ted retorts, “we’re not such idiots.” I wonder how Ted feels in 2021.