Hollywood has an enormous amount of work to do when it comes to depicting Native Americans, as well as in casting which actors to portray us.

The stereotype is infamous, of course: we were “savages” attacking white settlers, pagans who “didn’t know better.” And when not shooting arrows or beating drums, we guzzled firewater.

These stereotypes predate cinema. In Young Goodman Brown (1835), Nathaniel Hawthorne warned white America, “There may be a devilish Indian behind every tree.” With tomahawk in hand, no doubt, just waiting to massacre you and defile nearby women.

Such racism appeared onscreen from the very beginning, too. As early as 1895, Thomas Edison’s company released the short film Scalping Scene, which dramatized exactly what the title promised. By 1911, Moving Picture World observed, “The Indian, howling and scalping, killing and burning, is to a normal human mind a horrible and repulsive sight. We have had quite enough of him in moving pictures.” But audiences unfortunately had not had enough, not by a long shot… or a close-up.

Along with the literary and visual stereotypes comes “redfacing”: non-indigenous peoples put on makeup to pretend to be us, to darken and redden their skin.

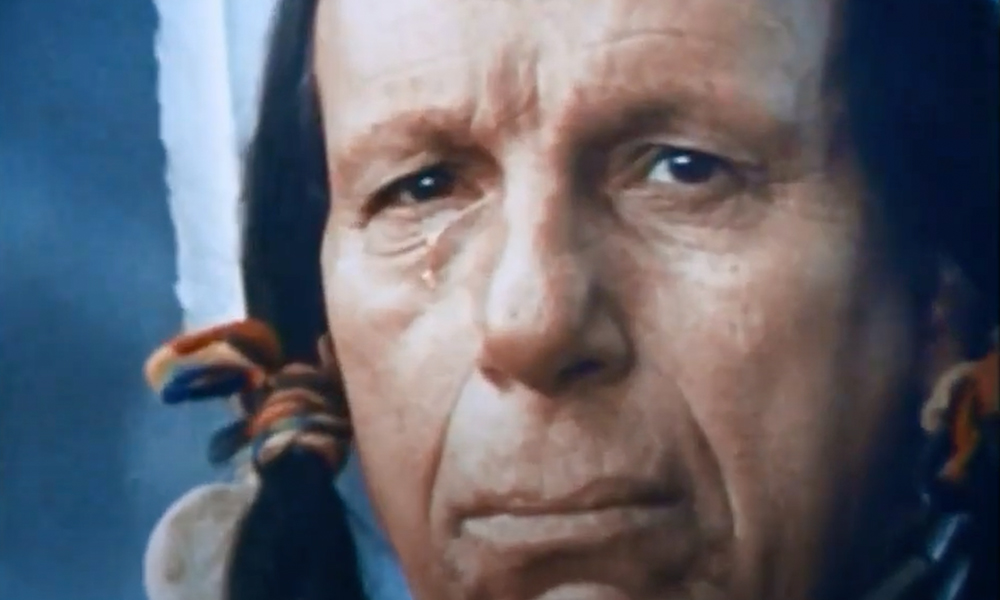

Consider Iron Eyes Cody, one of the most notable actors to play Native Americans during the 20th century. A tear fell from his eye in Keep America Beautiful, the famous TV commercial of the 1970s, in which a Native American despairs at the environmental destruction. The message was right. The casting was wrong. In real life, Iron Eyes Cody was Italian-American.

¤

Major league sports are currently paving a less stereotyped way forward, if only due to economic pressures. The Washington Redskins are, thankfully, no more. After dropping the “Chief Wahoo” mascot in 2018, the Cleveland Indians are also considering a name change. And even if the Atlanta Braves refuse to do the same, they are at least contemplating the end of their “tomahawk chop” nonsense.

And perhaps we can teach “progressives” in Hollywood — though the film capital has usually, with a few notable exceptions, ignored our advice for well over a century. Who can forget the importance, sincerity, and grace of Sacheen Littlefeather at the Academy Awards in 1973, taking the stage after Marlon Brando won the Oscar for Best Actor? She explained that Brando could not accept his award because of the “treatment of American Indians today by the film industry, and on television in movie reruns, and also with recent happenings at Wounded Knee.” There were boos, but there were more claps.

Thankfully, Native American directors have taken matters into their own hands, producing a large number of consequential films since the indie explosion of the 1990s. Parallel to their work are equally consequential Native American film festivals.

But the problems of stereotypes and redfacing continue in Hollywood even today. Johnny Depp is a great talent, truly, but an indigenous actor should have played Tonto in Gore Verbinski’s The Lone Ranger (2013). And desite its accolades, Bong-Joon Ho’s Parasite (2019) features a child pretending to be an American Indian, and particularly the scene in which his wealthy father dons a headdress and plans to act savagely at the child’s birthday celebration. The father even asks, “Isn’t this embarrassing?” For being the most recent recipient of the Oscar for Best Picture, yes, indeed, it is extremely embarrassing.

When it comes to advancing ourselves in Hollywood cinema, it is time to once again lobby for accuracy and authenticity. Marlon Brando bravely gave Sacheen Littlefeather her platform. Where are their successors in today’s Hollywood? Perhaps they will be Martin Scorsese, Leonardo DiCaprio, and Robert DeNiro with their upcoming film Killers of the Flower Moon.

We sincerely hope so.