For years it had seemed that this septuagenarian politician, a fixture in the country for decades, had finally retired from public office. But with a historic election looming, he throws his hat into the ring. His message is clear: this grandfather promises a return to the nation’s former values, those that have been trampled by a far-right government. Our country’s image has been thoroughly discredited abroad, he says, but in returning to the moral core of past generations, we can once again be proud of our home. Dismissing his opponent’s call for political revolution, he urges national healing instead.

Welcome to Konrad Adenauer’s 1949 campaign for German Chancellor.

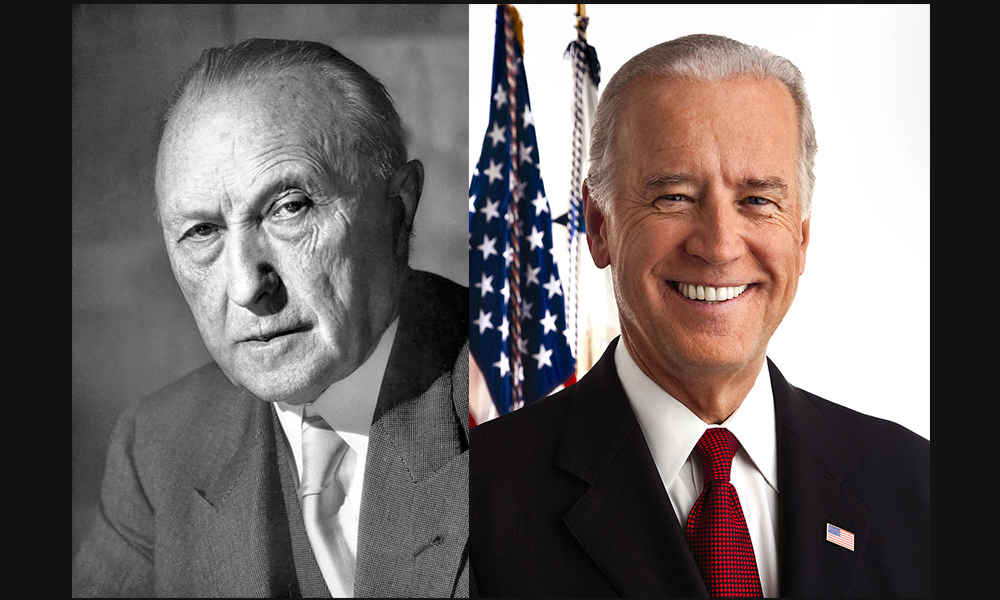

A household name in his home country, the founding father of postwar Germany is not well known to the average American today. And yet his message eerily resonates with Joe Biden, who just announced his candidacy for president. Calling for a return to the “American values” of past generations in his campaign launch video, Biden paints Trump as an aberration from a fundamentally good country. In doing away with him, Biden indicates, America can return to a good and just past, without upending the social or economic status quo.

As Democratic primary voters weigh Biden’s appeal, looking at the limitations of Konrad Adenauer’s similar vision — even in a different country and a different century — offers insight that is urgently needed today.

¤

As Germany emerged from the Second World War, most of the traditional, elite business and political class had been tainted by ties to Nazism. With the occupying Allies suspicious of anyone with connections to the old regime, the socialist Social Democratic Party (SPD) quickly emerged as the leading political force. With a decades-long record of anti-communism and anti-Nazism, the SPD was clear in its vision for Germany: united, neutral, democratic, and socialist. Nazism, the SPD argued, took power through the cooperation of capitalist elites looking to suppress the working class and their democratic political power. Only by moving forward with a new, democratic socialist vision of politics and society — thoroughly purged of the influence of Nazis collaborators — could Germany leave the stain of the Third Reich behind and forge a just country for all.

Konrad Adenauer took a different approach. The former mayor of Cologne who spent much of the Nazi years as a political prisoner, Adenauer benefited from being one of the few non-Marxists who had apparently not sought collaboration with Hitler (years later this would be proven false). His appeal to the German middle- and upper-class was obvious: the way forward for Germany was not by cleansing the country of past ills, but by resuscitating lost values. A devout Catholic, Francophile, and longtime critic of Prussian militarism, Adenauer encouraged Germany to look west to a socially responsible capitalism for salvation. Rather than attacking Nazism’s roots in Germany’s socioeconomic structure, Adenauer proposed a mere pruning of the most unseemly branches — confident that the tree would grow back flawlessly.

Under the influence of the Western Allies — who saw in Adenauer a fervent anti-socialist and anti-communist who would protect their business and military interests in the region — Adenauer gave the Germans who most needed to reckon with the causes of Nazism a way to avoid it. The clean break he proposed to West Germany was not with its Nazi past, but its Soviet-occupied Eastern half.

So when Adenauer took the helm of the newly formed West German government in 1949 — narrowly defeating the Social Democrats in the country’s first election — he made quick work of delivering on his promises. A market economy was re-established and quickly took off, with the Western world fawning over the Wirtschaftswunder, “the economic miracle.” Adenauer secured from the Allies a rearmament plan and, eventually, admission to NATO. Nazi symbols remained banned, and democratic elections continued. To many observers both outside and inside of the country, Adenauer appeared to have completely turned Germany around.

But underneath these glossy headlines lied a far more disconcerting reality. In order to fuel this mass capitalist economic growth and rearmament, Adenauer needed the help of the same business elites who had helped the Nazis expand their own economy and military. It required abandoning the aggressive de-Nazification trials that the Allies had imposed on Germany during their occupation.

Catering also to the votes of right-wing nationalist refugees from the East, Adenauer went to work: less than a week after taking office as Chancellor he introduced an amnesty law for Nazi war criminals. By 1951, it had exonerated nearly 800,000 Germans, including thousands of former Nazi Party members (including those in the SS) and tens of thousands who had been charged with murder. Adenauer even lobbied personally on behalf of the high-ranking Nazis convicted at the Nuremberg Trials, his efforts securing the early release of Konstantin von Neurath, Hitler’s Foreign Minister.

Adenauer went so far as to even bring Nazis into his government: in 1950 his administration was rocked by scandal when it emerged that one of his aides, Hans Globke, had played a key role in drafting the Nuremberg Race Laws. Adenauer would keep him on as one of his closest advisors for more than a decade after, even promoting him to his office’s Chief of Staff.

For those middle-class and elite Germans who had themselves been complicit in the Nazi regime, Adenauer’s tenure as Chancellor was everything they could have hoped for: renewed national prestige, a booming economy, and peace — all without ever having to answer for their role in creating a genocidal regime. The Social Democrats would be sidelined during this period, with much of their industrial base now behind the Iron Curtain (Adenauer had resisted overtures to re-unify the two Germanys in the early 1950s).

But the children who grew up during this German “miracle” were a different story. Many of them saw what their parents hid: a complicit past in enabling the rise of Nazism. The author Günter Grass captured this mood in his 1959 novel, The Tin Drum, which presented his generation as the protagonist, trapped in a childlike state and issuing a scream that can break glass.

Some of this generation took The Tin Drum too literally. In the 1970s and 80s West Germany was shaken by a wave of terror attacks by the far-left Red Army Faction (also known as the Baader-Meinhof Group), a group of young Germans who came to see armed struggle as the only way to root out lingering Nazi influence in the country.

The legacy of Adenauer’s policies are still felt today, with the Alternative for Germany (AfD) becoming last year the first far-right, nationalist party to enter the German Bundestag in decades. Advocating racist, anti-refugee views that harken back to the scapegoating of Jewish immigrants in the years leading up to Nazism, it’s no surprise that an AfD leader once described the Nazi era as “just bird poo in over 1,000 years of successful German history.”

¤

Obviously, we are not living in Nazi Germany — nor are we likely to be anytime soon. And yet, though Trump is not a totalitarian dictator, his rise has similarly reflected the culmination of years of capitalist crisis, hyper-nationalism, and racist structures reaching a boiling point.

So, in kind, as we look to the Democratic field for a leader to carry our country out of this nadir, we must be mindful of the lessons of postwar Germany: just throwing out some bad apples and calling it a day isn’t enough.

Joe Biden’s campaign stands unique now in mirroring Adenauer’s mistakes. Like Adenauer, his appeal is rooted in his antideluvian establishment bona fides. Like Adenauer, he harkens back to a glorious past, the “core values of our nation,” ignoring the role of the racist and capitalist values deep in our country’s history that pushed Trump into power. And like Adenauer, he thinks that cutting off the head of a far-right hydra is more suitable than pulling it out, root and branch — as difficult and even painful for the country as that may be. As The Washington Post reporter Dave Weigel tweeted the day of Biden’s announcement, “Other Dems talk about Trumpism growing out of policy failure. Biden describes one aberrant leader who must be replaced.”

What ails our country is deeper than just Trump in the White House. To cure it, Joe Biden’s half-measures won’t cut it. What we need instead is — in the words of another presidential candidate (bearing a passing rhetorical resemblance to Adenauer’s longtime socialist foe, Kurt Schumacher) — a “political revolution.”

Aaron Freedman is a writer based in Brooklyn, NY. Follow him on Twitter at @freedaaron.