“The ideal subject of totalitarian rule is not the convinced Nazi or the dedicated communist, but people for whom the distinction between fact and fiction, true and false, no longer exists.” –Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism

¤

Let’s begin with a warning. Before fascism takes hold in Sinclair Lewis’s vision of dystopic America, the protagonist — a liberal journalist called Doremus Jessup — gathers in a bar, warning his fellow patrons of the tyranny to come.

A business executive says, “That couldn’t happen here in America, not possibly! We’re a country of freemen.”

Jessup, outraged, gives the following reply:

“…Remember when the hick legislators in certain states, in obedience to William Jennings Bryan, who learned his biology from his pious old grandma, set up shop as scientific experts and made the whole world laugh itself sick by forbidding the teaching of evolution? […] Remember the Kentucky night-riders? Remember how trainloads of people have gone to enjoy lynchings? Not happen here? Prohibition — shooting down people just because they might be transporting liquor — no, that couldn’t happen in America! Why, where in all history has there ever been a people so ripe for a dictatorship as ours!”

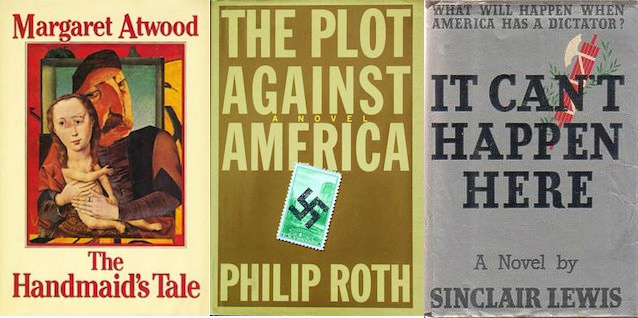

This was It Can’t Happen Here, published in 1935. In the novel, the charismatic Senator Berzelius “Buzz” Windrip runs on a platform of faux-populism, promising immediate prosperity to every American citizen. What ensues after his victory is textbook fascism: the silencing of political enemies, muzzling women and minorities, the thorough corporatization of American politics. Then come the concentration camps, paramilitary enforcement, and the silent acceptance of the American populace who assure themselves, long after the wrecking-ball has hit, that fascism simply “can’t happen here.”

We have all probably heard some variation of “it can’t happen here” from a sensible neighbor, colleague, friend, or family member since Trump’s election. But it is not unreasonable to be alarmed — let no one tell you otherwise. It is the necessary bedrock of action, just as denial is the bedfellow of passivity. It is easy to feel that with Trump’s election, we are shipwrecked on foreign shores, entering an unfamiliar landscape of horror. But this is more familiar than anything. Let’s not forget the tea bags our forefathers drowned in the harbor. Revolutions have been waged for less.

Most of our literature and history dramatizes the climax, the zenith of devastation, before the heroic denouement swoops in, just before we swing into true apocalyptica. Regimes have toppled with rolling heads, in lonely rooms with the slip of a cyanide pill, with royal families executed in basements, their bodies strapped with jewels.

But what I’ve been thinking about are beginnings. Most dystopian literature starts in the middle, or near the end. The beginning is when everything is still rendered in pointillist abstraction. There are a thousand permutations of America’s next step, and fascism may be 999 of them.

¤

“The trouble with Eichmann was precisely that so many were like him, and that the many were neither perverted nor sadistic, that they were, and still are, terribly and terrifyingly normal. From the viewpoint of our legal institutions and of our moral standards of judgment, this normality was much more terrifying than all the atrocities put together.” –Hannah Arendt, Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil

¤

Here is an excerpt from Trump’s inauguration speech:

“From this day forward, a new vision will govern our land. From this day forward, it’s going to be only America first, America first.”

This is not innocent political invective. Trump, foe to literacy, literature, and history scholarship, might not be aware of the historical connotations of the “America First” slogan. But his white supremacist speechwriter Steve Bannon surely does. “America First” is not a “new” vision. Before the attack on Pearl Harbor, the America First Committee (AFC) was an isolationist and nativist anti-war political group. Chief among its members was famous aviator Charles Lindbergh, who delivered an anti-Semitic speech discouraging the US from getting involved in the Second World War.

In 2004, Jewish writer Philip Roth published The Plot Against America. Like Lewis’s It Can’t Happen Here, Roth’s alternate history imagines how fascism might take over America. In his novel, the point of divergence is the election of Charles Lindbergh, under the “America First” party, as President. It begins slowly, the anti-Semitism insidious and subtextual until the mechanisms of power drag it unapologetically into the open.

A Plot Against America is about terror — the most ordinary banalities of everyday life threatened by the constant hum of violence. But Lindbergh does not personally break every window, set every car aflame, murder every innocent Jewish person who crosses his path. Lindbergh empowers the anti-Semitic Americans who mean to do Jewish people harm, just as the anti-Semites empower him to hold office.

Stokely Carmichael once said: “If a white man wants to lynch me, that’s his problem. If he’s got the power to lynch me, that’s my problem. Racism is not a question of attitude; it’s a question of power.”

This is how beginnings become rising actions become disasters. Hannah Arendt’s definition of power in On Violence provides a road map for how fascism can take root. “Power is never the property of an individual; it belongs to a group and remains in existence only so long as the group keeps together. When we say of somebody that he is ‘in power’ we actually refer to his being empowered by a certain number of people to act in their name.”

Within this definition is also a toolbox for taking power away. A fascist can only be powerful so long as the people empower him.

¤

“There is hardly a better way to avoid discussion than by releasing an argument from the control of the present and by saying that only the future will reveal its merits.” –Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism

¤

During the historic Women’s March last Saturday, it wasn’t Lewis or Roth or even Arendt I was thinking about — it was Atwood.

In The Handmaid’s Tale, Margaret Atwood imagines a future America where women’s autonomy returns to a Dark Ages chokehold thanks to the machinations of radical evangelists. “Handmaids” are fertile women tethered to married couples who can’t conceive. Women are second-class citizens, denied the right to eat when they want, live where they want, love who they want.

Unlike The Plot Against America, the terror in Atwood’s novel does not come from the threat of violence — it comes from being completely sequestered from information. Even the most basic facts are kept from the women in The Handmaid’s Tale. The protagonist Offred, hungry for literature, is given no books or newspapers. She reads a pillowcase in her bedroom, over and over again. She finds a scrap of Latin carved into the wall.

There is a reason totalitarian regimes disdain literacy — withholding culture is the easiest way to disempower.

But the estimated 750,000 people who came to the Women’s March in LA used culture like armor. Everywhere you turned, there was a display of artistry, wit, or rage to feast your eyes on. Not only was it a parade of the thousands of different people that make up this country — none of them poorly toupee’d or cheeto-dusted — it was a celebration of art. A rich gallery of symbols crowded the streets, from Leia’s braided crown to Beyoncé anthems to the sea of cat-eared pink hats. Armed with fiction, song, memes, and art — from cleverly-crafted puppets and piñatas to hand-painted parachutes — the city of LA weaponized its creativity.

An entire century of intergenerational experiences crowded into a mile-long strip of downtown LA. Children with hand-made posters, old women with Planned Parenthood signs strapped to their backs, military veterans. Wheelchairs, baby strollers, wagons. Men with crinkly-eyed smiles and orange turbans doling out styrofoam bowls of free food. Black women, Muslim women, Japanese women reminding marchers of the recent horrors of internment. Men with daughters on their shoulders, moms carrying their sons. Teenaged, college-aged, middle-aged, every-aged men who showed up with no women at all.

The March accomplished what art is supposed to do. It had music, expression, creation. It spread and multiplied like a song. It reflected on its own existence. It was an occasion to put your body in the street with other bodies — strange, friendly, familiar, familial — to add your voice to a chorus on the Metro, a chant on the street. The March was a bright spray of hope — maybe this is the end. Maybe this is fascism’s last gasping breath, the death-rattle of a system in decline, a house of cards destined to collapse on itself.

Or maybe this is the beginning of the Orwellian nightmare. I can’t help but look for the point of divergence at every corner. Is this when it happens? When we slide into The Handmaid’s Tale, The Plot Against America, The Man in the High Castle?

Revolutions, protests, and civil unrest have defined every wrecking-ball swing and gentle tug of history since the dawn of time, yet we are still stuck in a bourgeois distaste for it. We have always had to demand our rights. Nothing has ever come from waiting.

Early in the novel, long after democracy has fallen, Offred muses, “I would like to believe this is a story I’m telling. I need to believe it. I must believe it…If it’s a story I’m telling, then I have control over the ending.”

Let’s be hyper-literate. Let’s erase Trump as the subject of the story. Let’s live not in the margins where he wants us, but scribbled over the page, in brighter and bolder ink. Let’s crowd the airwaves and the magazine pages and the bookshelves and the subway cars and the streets with everything that is defiantly not-Trump. Let’s drown his babel with our own.

The triangulations of alarm, idealism, hope, and terror which produce action are within reach. This is the beginning of a long, long fight. What are you doing today?