This April, perhaps more than any other that I’ve lived through, I thought about time — how it writes us, how it shapes and reshapes what we write. These reflections led me to revisit the work of a poet whom many readers may know by name but few are familiar with: Edna St. Vincent Millay. What follows is the series of musings which emerged from feeling myself acted upon by our own time — and Vincent’s.

I. Vincent

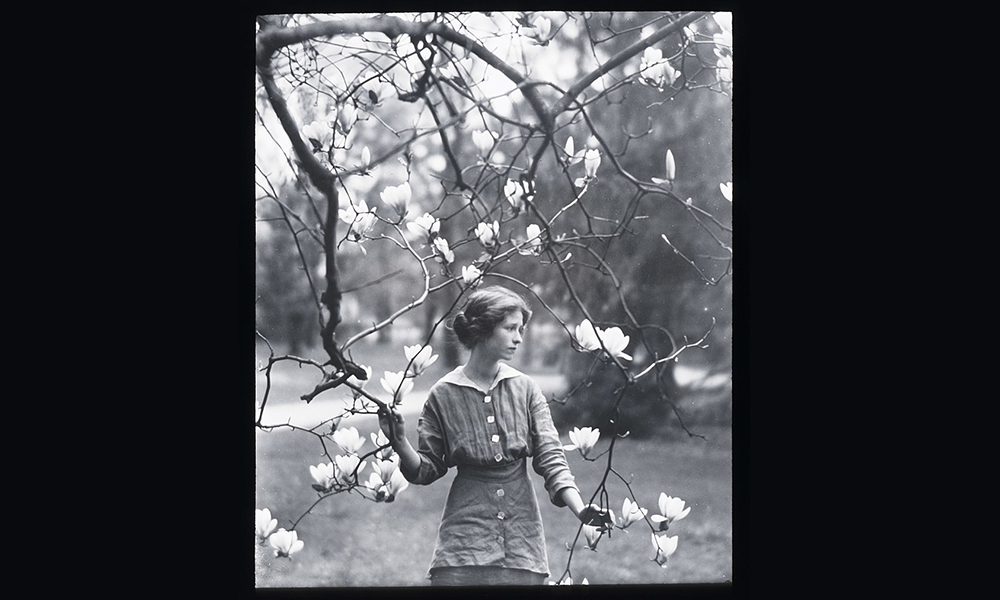

Magnetic was the only word for her. With her red hair bobbed, she might have been a medieval pageboy, this woman with a boy’s name who breathed syllables in languid spirals between drags from a cigarette. She turned people into moths to her flame.

Who could have known that her candle burned at both ends?

In December 1920, the celebrity poet Edna St. Vincent Millay — Vincent to her friends — read her work aloud to a packed auditorium at her alma mater, Vassar College. So large was the event that it overflowed the Assembly Hall and had to be moved at the last minute to the larger Students’ Building. Like a popular singer, Vincent took requests from the clamoring crowd. At one point, it seemed as though the applause would never end. Such readings were nothing new to the charismatic young woman. Though her light has faded today, she was hailed in her lifetime as “the greatest woman poet since Sappho.” In 1923, she became the first woman to win the newly created Pulitzer Prize for Poetry. A national superstar on a level not seen afterwards until Amanda Gorman, Vincent traveled all over the country reading her work to adoring crowds. On this particular evening, however, a 10-year-old specter of love and loss lingered over the hall. The ghost’s name was Dorothy Coleman.

Of the many poems with which Vincent favored her fans that evening, a handful were the basis of a forthcoming spring-themed collection, The Second April (1921). These struck an unconventional note. The Vassar Miscellany News would later report that “they breathed a gloom so unmitigated as almost to outweigh their lyrical quality.” Like spring, these poems had grown out of a barren landscape — they had emerged in the aftermath of a pandemic.

II. April, Again

Pandemic literature means more than feeling seen by history. It gives us new ways of seeing, new ways to peer gingerly out at the world from within the houses of ourselves. At the bottom of our instinct to search for versions of ourselves in Boccaccio, Defoe, and Shakespeare is a question about how to look upon things once familiar now that we, in Vincent’s words, “know what we know.”

Just two years before Vincent’s reading at Vassar, the 1918 flu pandemic gripped the United States. One of the casualties was 18-year-old Dorothy Coleman, her close friend and classmate. Although the exact nature of the young women’s relationship is uncertain, there is speculation that they were lovers. Coleman’s death spurred a period of intense creativity for the young, grief-stricken poet. That same year, she produced a collection of five poems, Memorial to D.C. Upon reading these, Dorothy’s mother wrote to Vincent with mixed feelings. She was grateful for the tribute to her daughter, but disturbed by an unkind reference in one of the poems, “Dirge,” to Dorothy’s “arrogant brow” and “withering tongue,” which she attributed to a bitter quarrel between the two girls. Mrs. Coleman’s perusal of her dead daughter’s diaries had revealed, she told Vincent, that Dorothy “was greatly attracted to you, that she was very happy in having gained your love but in the end she seems to have been a little frightened by your genius.”

Vincent never cut the offending lines. Over the next couple of years, she expanded the memorial into a collection which confronted springtime with mortality. Before T.S. Eliot published his now-canonical lament that “April is the cruelest month,” Vincent wrote bitterly that “April / Comes like an idiot, babbling and strewing flowers” (“Spring”). The loss of Dorothy turned Vincent’s world into a “lovely, lovely tattered mist” (“The Blue-Flag in the Bog”). The poem from which the collection takes its title, “Song of a Second April,” looks out onto a world that is unchanging in its first lines and vastly changed by its last:

April this year, not otherwise

Than April of a year ago,

Is full of whispers, full of sighs,

Of dazzling mud and dingy snow . . .. . . only you are gone,

You that alone I cared to keep.

A hundred springtimes later, Vincent’s Second April tells us about our own. She asks a question that echoes in our hearts as we begin to contemplate returning to the world: what can beauty say to the knowledge we have garnered between our Aprils?

This April, we are other than we were an April ago. These poems help us to find language for how it feels to have “forgotten how the frogs must sound / After a year of silence,” for the way we’ve grown accustomed to the safety of enclosed spaces and wary, in spite of ourselves, of the “savage Beauty” of the world outside. Finding ourselves changed in an unchanging world means finding ourselves in a new place. In the months and years to come, we will find that we are new people in all the old places.

Recently, I sat beneath a large oak with Vincent’s words and the Appalachian mountains spread before me. For the first time in a year, I registered the pungent smell of mulch, stronger than springs past in my memory, now tyrannized by a white-walled nothingness, a benumbed remnant of the wood-and-hearth aroma of home. A breeze brushed through branches somewhere over my head, where birdsong was. The vividness of everything was offset by a strong, peculiar impression of having been transported into the elsewhere. It was difficult, though at the same time deeply magnetic, to trust this space. I felt all that had and had not changed about the world in a year of absence from it: “only the light from common water / Only the grace from simple stone.”

III. Words Unseen

We cast our words upon the world, simple stone into common water, in the hope of — what?

“Margin me with scrawling,” answers Vincent.

A century has responded largely with silence.

There has never been a better time to question why we choose to see what we see. Second April invites us to rethink how we have historically undervalued women’s achievements. Literary immortality is Vincent’s answer to death. In “The Poet and His Book,” she calls upon the unknown reader of the future from the moldering mess of a secondhand bookseller’s stall to

Lift this little book,

Turn the tattered pages,

Read me, do not let me die!

Search the fading letters, finding

Steadfast in the broken binding

All that once was I!

All that she was should give us pause. Vincent was a popular sensation. She traveled across the US reading her poems to packed auditoriums and was the first poet to have her own on-air reading series on radio. Her volumes were national bestsellers at the height of the Great Depression. For Thomas Hardy, America held two attractions: the skyscraper and Edna St. Vincent Millay’s poetry. The first female recipient of the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry was also the epitome of the powerful, modern woman. The sensuality of her lyric was paralleled only by her seductive confidence, her famous green eyes and golden-red hair — and her even more famous affairs. She was also a political artist who channeled her passion for democracy into activist poetry. As fascism and communism rose in pre-World War II Europe, she told a New York Post reporter about her experimental poem, “Conversation at Midnight,” that “The liberty under which this new book of mine comes out is more precious to me than anything anywhere. That’s what makes life real.” And it was within the poet’s power to defend that liberty.

That a poetic titan went from setting the scene to unseen is worth considering — and reversing. Words speak across centuries if we choose to hear them. Poetry may be life-giving, but the reader’s gaze has the power to confer immortality or death. Vincent toys with the idea of her own literary demise with the intention of outliving herself. Yet the last hundred years have seen her overshadowed by T. S. Eliot, e e cummings, Ezra Pound, and other modernists. The time has come to rekindle her flame and bring her back into our line of sight — to be awed by the genius of this female pathbreaker — for she has earned her place, and she speaks to our time too.