Throughout the fall and winter of 1958, Jane Jacobs huddled wrapped up on the bed in a room on Bethune Street in Greenwich Village. The room was often unheated, and the bed was warmer than sitting at the desk. She lived around the corner, on Hudson Street, but her home was always chaotic and bustling, and she needed a quiet place, “a room to work in, where I am uninterrupted by people, telephone, etc.” In this studio which she rented for eight dollars a week, Jacobs wrote what would later come to be known as one of the most important nonfiction works of the 20th century.

Rereading The Death and Life of Great American Cities during the pandemic is something of a masochistic act, an utter failure at the escapism that I’ve otherwise tried to engage in for the past two months. The first time I read it, I was far away from any American city, but I read it again as soon as I arrived in New York City, soaking my skirts in Washington Square Park fountain, the ink from my scribbles bleeding across the pages under the water spray. From where I sat I could see straight up Fifth Avenue; in Jacobs’s time, the fountain was 22 feet further west, tucked away off-center and more sheltered from the thoroughfare by the Washington Square Arch. Whenever I look through it I’m reminded of a January night in 1913, when there was a policeman stationed there who happened to wander away from his post.

He’d been assigned to patrolling the arch a few months earlier, when it had been discovered that a vagrant had been living inside it, drying his clothes on the parapet. While the officer was away, the downtown painters Marcel Duchamp, Gertrude Drick, and John Sloan, and Provincetown Playhouse actors Forest Mann, Betty Turner, and Charles Ellis, snuck their drunken way up the one hundred and ten unguarded iron stairs and onto the roof of Washington Square Arch. They lit a bonfire and passed around wine, then read a declaration consisting solely of the word “whereas” repeated over and over, and then ended by proclaiming their territory the Free and Independent Republic of Greenwich Village. They signed a parchment with the Great Seal of the Village, fired pistols, released lanterns, tied red balloons to the arch, and wandered off at dawn. The door to the stairs at the base of the arch has been permanently locked ever since.

I have always spent countless summer hours soaking in that fountain with a novel or a notebook, dreaming about the characters who have passed under that arch over the past century, and about the ones that pass under it today, the musicians and the hipster typewriter-poets, the yelping children and the man who makes human-sized bubbles for them, the green human statue named Juan. The joyous and madcap activities that have found safe harbor in this park long predate Jane Jacobs, and certainly the chaos continued during her reign over it; Washington Square Park has always been my first New York reminder of why, so often, I find a specific kind of peace and joy and comfort in strangers that I do not find in even in my loved ones. The fountain usually turns on this month; this year I likely won’t know when, if at all, it does.

There are, of course, far worse problems that New York City is dealing with right now than the death of its bustling street life. But Jane Jacobs would have been 104 years old today, and her birthday seems an appropriate day to remember what there is to look forward to whenever we can safely emerge again, and to appreciate from afar the small urban joys that have up until this point been the core of lives like mine.

Under quarantine I have seen people making greater efforts to reach out to the people in their lives, to check in on friends and family more, especially those get-togethers that in real life are often postponed. It’s been touching to be surrounded by these gestures of care, particularly since they are gestures I myself am quite poor at. But while many of our relationships with friends and family are, blissfully, able to attempt this gentle and only sometimes awkward transition into the virtual, there are many other relationships that by definition cannot do this; relationships that by definition are attached to the constant and comforting physical space they occur in.

One of the critical experiences Jacobs articulates about life in big cities is that of privacy; it is a rare and very valuable commodity, and one of the things that makes city life so attractive. But it also exists, she points out, in a delicate state of balanced layers. Privacy is made possible by the complete anonymity of the city, but complete anonymity does not support the kind of trust that Jacobs contended was vital for cities. An essential middle tier of people — the people who are unfailingly, consistently on the periphery of one’s day — guarantee this privacy, and therefore this other kind of trust. Of these people, Jacobs writes,

The trust of a city street is formed over time from many, many little public sidewalk contacts. It grows out of people stopping by at the bar for a beer, getting advice from the grocer and giving advice to the newsstand man, comparing opinions with other customers at the bakery and nodding hello to the two boys drinking pop on the stoop eyeing the girls while waiting to be called for dinner, admonishing the children, hearing about a job from the hardware man and borrowing a dollar from the druggist, admiring new babies and sympathizing over the way a coat faded… Most of it is ostensibly utterly trivial, but the sum is not trivial at all.

This middle tier — those who are neither friends or family nor strangers — keep a city alive. The falafel seller outside our office building who is always ready with our lunches but also often offers lighters and cigarettes as easily as his food, who always has a running list of regulars who take sodas on credit, who frequently loans me orange juice if I look too hungover, is not someone I can get on the phone with now, though I have spent days having a meaningful conversation with nobody in my life but him. Neither are my bartender, who keeps refilling my glass into the late hours as I sit alone at his bar and read or write or work, or the men who run the bodega around the corner where I will sit on the floor for hours as people come and go, rocking back and forth and hugging the shop cat. These are men who have held onto my secrets that may be harder to share with family or friends, my house keys and my mail that may be harder to share with my next-door neighbors. According to Jacobs, this is because people in their position have so many relationships just like the one they have with me, that they are not particularly interested in my private affairs.

This distance is crucial to the specific trust we share. “It is possible in a city street neighborhood to know all kinds of people without unwelcome entanglements, without boredom, necessity for excuses, explanations, fears of giving offense,” Jacobs writes. These relationships are possible, and important, “precisely because they are by-the-way to people’s normal public sorties.”

In New York, a really wonderful walk is made up of its detours; a really lovely day is made up of the by-the-ways.

But there is no by-the-way about a Zoom call or a Google Hangout; there is an intentionality about interactions and relationships in the age of this pandemic that is completely absent from some of the most interesting interactions that take place in the city — ones that simply offer a certain kind of freedom, a unique combination of anonymity and intimacy, that cannot be found in my interactions with loved ones. In talking to a stranger at a bar, rather than the coworkers or friends that I didn’t come to the bar with, I am in a way talking to myself, or to the city.

Jane Jacobs didn’t want to be an activist. She wanted to be a writer; she wanted to follow her senses all over the city, writing about the intense pleasures and oddities that filled it. Robert Moses kept messing up this plan, forcing her out onto the streets with his absurd proposals; if she’d felt she had the freedom and the room to pursue her career without risking the death of her neighborhood, she might easily have become a reporter and chronicler of city life akin to the likes of Meyer Berger or Gay Talese, whose metro reports in The New York Times contain some of the most memorable details ever captured about the city.

Long before she became a Greenwich Village fixture, Jacobs was writing sensory, new journalism-style magazine pieces for Vogue about the garment and diamond districts near Seventh Avenue, the flower markets, the leather industry, all offering a glimpse into the business of fashion. From her little apartment in Brooklyn Heights, she would get on the subway and emerge at various stops at random. One day she got out at Christopher Street, because she just “liked the sound of the name,” and ended up spending the entire day walking the streets of the neighborhood.

Greenwich Village was one of the few neighborhoods in Manhattan that deliberately did not follow the grid system, and therefore didn’t have the artifice of the rest of Manhattan. Jacobs wandered around the bakery selling nickel-loaves, the candy store, the speakeasies, the craftshop, the cheese shop, the second-hand bookshop, and the mysterious streets that disappeared after only one block; she finally trudged home at the end of the day, and hauled back at the first opportunity. Within a few months she was living in the neighborhood where she would spend the next three decades.

That there is no alternative to the lockdown makes it all the more saddening to think of the city in the summertime, and all of the spontaneous moments and urban joys that cannot be replicated within the confines of a little New York apartment. But nevertheless I have found it somewhat comforting to reread Jane Jacobs recently, like keeping a photograph of a long-distance lover tucked into the pages of my bedtime novel, looking at it constantly as though to remind the both of us of the weight and beauty of what I hold, until the other can heal and is safe to come home again.

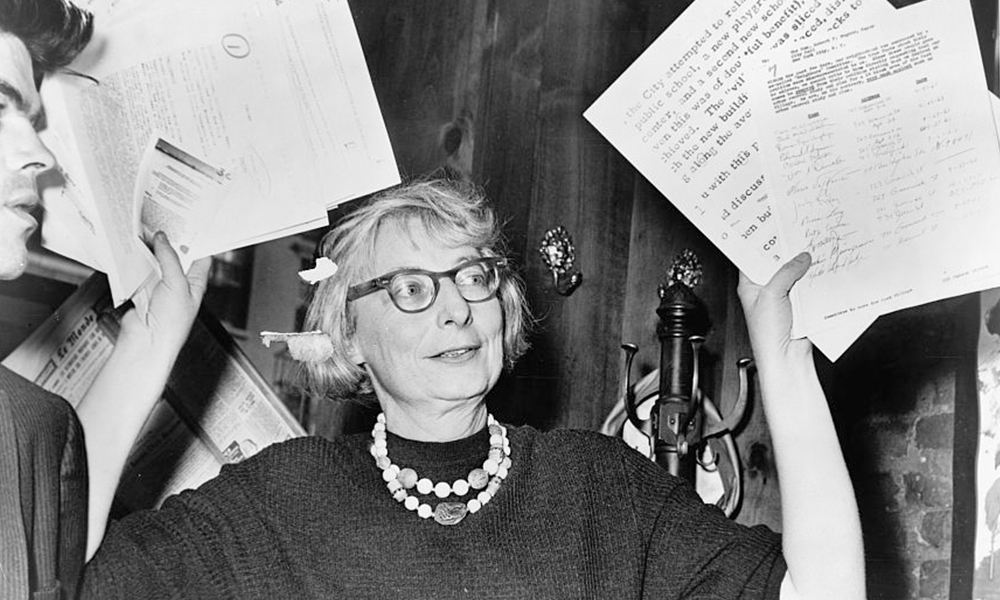

Photo: Phil Stanziola. New York. December 5, 1961. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/2008677538/>.