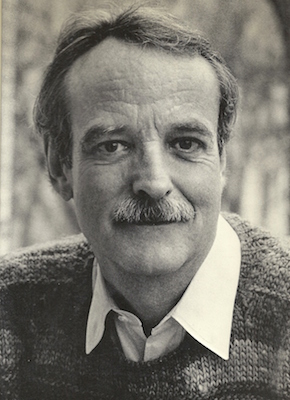

The recent death of book editor and writer William McPherson prompts heartfelt memories of a moment in a bygone East Coast literary Elysium that he shepherded — incidentally changing my life.

No doubt Bill, editor of the Washington Post’s Book World, would caustically comment that, as a first sentence to a remembrance, the words above were too sophomoric and sentimental. Especially because they reflected on him. I can see him looking up with a friendly smile and calling the sentence self-aggrandizing and “schmaltzy,” which I would take with a grain of salt as a waggish nod to my roughhewn New York ethnicity.

But then, back in the late ’70s, Bill might haughtily approve of the campy lead as something that would appeal to our typical maudlin readers. And off we’d go, along with whoever else was standing in his book cluttered office at the time, into the eternal debate over who the reader we were writing for actually was.

I might have cited such self-anointed authorities as my former editor at The New York Times, A. M. Rosenthal, whom I remember declaring that the archetypical reader was a precocious nine-year-old. But of course Abe would say that, Bill would retort; he himself having the disposition of a nine-year-old. Bill was wonderfully witty and judgmental, which made him a beloved editor among us bitchy scribes.

Or maybe the reader was the bright, bookish special assistant to a calloused congressman, as Bill’s quick-with-a-quip boss Ben Bradlee might suggest. Jane Howard, my then companion, would remind us that the reader was likely a she — and she’d be right.

Jane was a best-selling author (A Different Woman) and close friends with Joan Didion, with whom she’d been celebrity writer for a celebrated Life magazine. Jane was also a longtime friend of Bill’s. She and I would visit him in D.C., as would other writers, in effect forming a floating salon.

Wanting to end the blather about our readers, Bill would offer up a remark from the comic strip Pogo: “We have met the enemy, and he is us.” Bill had spoken, a second cup of coffee or glass of wine would be poured, and we’d move on to the next topic or personality to be skewered.

One day at the Post in the fall of 1978, as I stood in Bill’s office looking through a stack of recently published books to chose one I would review, the topic he casually introduced was the possible end of his tenure as the editor of Book World. My immediate concern, of course, was that a new editor, as is their wont, would have his or her friends and favored reviewers, and my assignments would therefore diminish, if not end. But then my thoughts quickly turned to friend Bill.

As Bill told it, that morning Ben Bradlee had, almost off-handily, asked him whether he wouldn’t rather be a writer or book critic, rather than editor of Book World. This would give him time to work on that novel he wanted to write; besides, he himself had always contended that writers had more fun than editors. We writers agreed, even though we thought editors were paid more for being less creative while sitting in a comfortable office protected from the elements, with an intern close by to get them a coffee. What did they do, really?

Apparently Bradlee had already offered the editor’s job to Book World’s dependable deputy, Brigitte Weeks, who had received an offer from the then ascending Los Angeles Times. Bradlee did have the reputation, in those haughty post-Watergate warrior days, of stabbing employees in the heart with a sharp rapier, which, we all felt, was better than being stabbed in the back, as is the style of most senior editors.

It might be of interest to nostalgic readers that the man overlooking the “soft” news and Book World at the time was the smarmy, smiling Shelby Coffey III, who would later become the unctuous executive editor of the Los Angeles Times. Try as he might, Coffey could never exude the spirit and style of the benevolent Ben, and it would have been easy for Bill to stand his ground.

But it was hard for Bill to argue with the august Bradlee, since it was the Post that hired him in 1958, at the age of 25, as a raw copy boy, despite him having dropped out of college twice. And after becoming a reporter a few years later, Bill impetuously left the Post for a job in book publishing, but Bradlee had lured him back with the book editor position. Not only that, he signed the checks. And if you were nice, he and his glamorous wife Sally Quinn might invite you to their storied dinners.

There would be no discussion among friends and associates that day, for Bill declared he had accepted the new assignment. He looked forward to being a journalist again, and, in time, a writer. He added that he actually had the beginnings of a book on paper, with the story shaping in his mind, though would say no more.

It was this jumping from rock to rock in the merging currents of journalism and literature that made Bill a kindred soul, for I too had a fractured career. Among questionable pursuits, I had worked on New York’s waterfront as a “shtarker” and upstate as a seasonal farm laborer; Bill had been a merchant seaman. But I had eventually graduated from Cornell University, which, after a forgettable stint in the army, had no doubt helped me score a job as a copy boy with the New York Times, also in 1958.

Thus we became confiding friends, in the spirit of strangers sitting next to one another on a long sleepless flight, sharing confidences. Except that Bill and I would meet again for years to come, sporadically, especially after I left the New York Post, where I was briefly an editor for Rupert Murdoch, to take a position with the newly minted Carter administration in Washington.

And so, that day, while friend Bill was talking about his new job and reassuring me Brigitte would make a fine editor, and, presumably, be pleased to continue to use me as a reviewer, he stopped and smiled broadly. Then, after a pause for dramatic effect — 40 years later, I remember this distinctly — he suggested I should immediately apply for the book editor post that Brigitte was, at that very moment, calling LA Times editor Jean Sharley Taylor to turn down.

He declared I would be perfect for the rising LA Times, having written reviews for the New York Times under the tutelage of Eliot Fremont-Smith, and for the edgy Village Voice under editor Dan Wolfe and infamous publisher Norman Mailer. And, of course there were the pieces I had written for him at the Post. He noted that, thanks to my Ivy League education, I dressed British, but, being from Brooklyn, thought Yiddish.

Bill handed me his phone, and I got through to Taylor, who said, yes, Weeks had just turned down the job, but the paper had a second choice in the wings, their columnist Art Sidenbaum. He had accepted just minutes ago. Then Taylor mentioned that the cover the paperback of my book The Dream Deferred had prominently quoted a rave L.A. Times review — and asked whether I’d be interested in coming to the coast and discussing Sidenbaum’s former job as an urban commentator.

My hand over the phone, I relayed the query to Bill. He nodded yes enthusiastically. Bill was, of course, right. My professional job in government was mostly bullshit, a divorce was pending, my fickle friend Jane was researching another book and had sublet her apartment, at my suggestion, to former colleague Syd Schanberg, who was returning from the tragic killing fields of Cambodia to become city editor of the N.Y. Times. For those of us who had climbed on the journalistic wagon in the late ’50s, it was a small world.

What the hell, I thought, flew out to Los Angeles the next weekend, loved what I saw, and moved a month later. My thought was that the assignment was, in effect, a generous travel and study grant to Southern California, and I’d probably return to New York in a year or two. That was nearly 40 years ago.

I never saw Bill again. We were going to have drinks, but instead said our goodbyes by phone, promised to keep in touch, and didn’t. I did send him a note in 1984, congratulating him on the praise for his novel, Testing the Current. He never answered, and when his second novel, To the Sargasso Sea, came out in 1988, I didn’t send a note, but I was happy for him.

Bill left the Post a few years later, more or less when I left the L.A. Times. I heard he had gone to Romania as a freelance writer, which would not have been my choice. I became a creative consultant to Disney Imagineering, while continuing to write. When I asked John Gregory Dunne, whom I had met through Jane, why he thought Bill had become an ex-pat correspondent, he had no answer. This was soon after the great success of John’s True Confessions. Changing topics from Bill to me, John asked, ruefully, why I had stayed in Southern California. “It’s comfortable, “ I said. “Corrupting,” he added. And, for the literary world, “corroding.”

Then, inevitably, mortality began taking its toll. First Jane passed, then Art, John, Sydney, and Dick Eder. Others. Not having heard from or about him for years, I thought Bill had also passed, only to read in 2014 that he was back in Washington, his health dwindling, and his finances worse. He chronicled his ill fortune in an essay for The Hedgehog Review, titling it “Falling.”

It was a sad, indeed tragic, tale. But the topic was substantive. As an editor, Bill would have approved. It was worthy of a novel, or at least a long discussion at a salon.