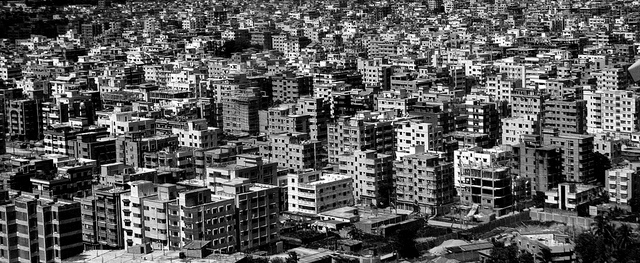

Poor countries like Bangladesh, with their large labor diasporas and internationally connected or aspirational elites, tend to be far more globalized than rich ones. Given the highly visible role that foreign trade, philanthropy, and development play in their societies, such nations stand at the forefront, if not on the front line, of globalization. The brutal events at Dhaka’s Holey Artisan Bakery on the first day of July serve as an instructive illustration of this reality. The “artisanal” restaurant, with its European and Latin American chefs, its clientele of diplomats, aid workers, and NGO interns from American universities, and, indeed, the internationally educated students from affluent families who attacked them — all were global citizens. It was as if Dhaka provided an arbitrary site for their collision. There was nothing very local about any of the concerns animating the restaurant’s visitors — least of all the murderers, for whom Bangladesh itself was of no particular interest.

Of course, the globalized form of militant Islam that unleashed this savagery didn’t just touch down in Dhaka randomly. In some ways it illustrated the dark side of the humanitarian enterprises that motivated many of the Holey Artisan Bakery’s diners, with their focus on addressing injustice and inequality globally. Moreover, the jihad inspiring some half a dozen Bangladeshi youths to kill these well-meaning men and women had as its context the absence — in fact, the repudiation — of a local or national politics. For both the NGOs and terrorists, who work outside political institutions they often despise and seek to transcend, were matched in Bangladesh with an authoritarian government dedicated to eliminating its parliamentary opposition, which is itself rather unsavory, thereby creating a depoliticized state. Perhaps militant politics, then, is a preliminary or self-annulling practice, whose language of conflict is simply meant to replace government with governance, essentially mirroring Bangladeshi authoritarianism. Or maybe its concern with fighting for the global community of Muslims it sees as under attack is anti-political by definition.

The problem of identification

If both the leftist Occupy movements and rightist anti-immigrant parties in Europe and America represent a protest against globalization, then militant Islam today may be a protest in favor of globalization’s fulfillment. After all, the anti-globalization movements seek to reclaim a lost politics of class or nation, while Muslim terrorism, despite its deployment of political categories like states, peoples, and conflict, does just the opposite, trying to achieve a depoliticized society under an unalterable and unquestionable divine law. In fact, Islamist and militant groups have always been mistrustful of the state and its politics. In this way they resemble, at least in their aims, otherwise very different projects — ranging from the authoritarian state to the neoliberal market-driven Islam of places like Malaysia or Turkey.

Like all globalized phenomena, Islamic militancy often escapes the arenas of national or even international politics, and can move easily from one context to another. It remains unclear whether movements like Al-Qaeda or even ISIS want to found a global politics or destroy its very possibility, an ambivalence manifested in the violence they both wreak. Militancy, as much as philanthropy, is obliged to speak in the name of vast and supposedly victimized constituencies like the “global South” or the “Muslim community,” which cannot represent themselves in any formal way because they don’t enjoy any kind of political existence. And just as with international NGOs, which claim to speak for humanity while remaining unaccountable to all but their donors, militant Islam struggles with the contradiction of identifying with victims who can never acknowledge this fellowship.

The French sociologist Luc Boltanski defined this problem as one characteristic of the media-diffused spectacle of “distant suffering” that serves as a call to humanitarian action. In the absence of an immediate political solution to this suffering, the spectator’s outrage is turned inwards, into a searching examination and criticism of his own guilt, pity, or sentimentality. It’s easy to see how self-sacrifice in its various forms — including dedicating time, money, and skills, as well as weapons or violence in the victim’s defense — might emerge as the strongest response to the call of such suffering. This is especially true when the victim in question is a rather abstract entity, lacking any political reality, like humanity or the Muslim ummah. To sacrifice oneself is to eliminate, willfully, the distance between oneself and the suffering of others. But in the absence of politics this enterprise remains deeply narcissistic, so that today’s militants also compel others to share in their suffering, as if desperate to make visible a real community of victims and spectators.

Hannah Arendt traced the violence with which such pity sought to annul itself in sacrifice to the French Revolution, and so to the historical beginnings of terror. In her view it was the “social question” posed by large-scale inequality, poverty, and oppression that gave rise to pity and its peculiar forms of violent identification, which sought to resolve suffering’s apparently intractable reality through revolution. However, she believed that to address the social question through politics in such a direct fashion was to destroy the latter’s institutions and integrity. But today, with the globalization of identification, suffering seems to have been removed from the province of political institutions and even revolutions altogether. Now suffering can be addressed only in unmediated forms of “moral” outrage and social violence, an approach far worse than even the most cynical of politics.

Politics after globalization

Recognizing its violent potential, Gandhi was one of global identification’s most important critics. He consistently refused to speak or act in the name of humanity, considering this a deeply hubristic and narcissistic enterprise, precisely because it was a politically impossible one. And yet the Mahatma didn’t condemn the idea of universality, and thought that nonviolence, for example, was capable of global expansion. But this was only possible by way of personal example and without making a mission out of it. Instead, as the project of nonviolence spread, control over it had to be constantly resigned. Gandhi described this process of expansion by way of resignation as constituting an “oceanic circle,” where the self-rule of single villages spilled over into that of districts, provinces, the nation, and beyond, without any central authority.

Gandhi’s vision of nonviolence as a practice of sacrifice spread by example, without requiring a central authority for its propagation, appears to describe the very way in which Islamic militancy works in our own time. But in his view this similarity would have allowed for the conversion of one kind of sacrifice into another, drawing out the common idea of goodness by which he thought evil was sustained, and so causing the latter’s collapse. The Mahatma, in other words, would have understood the attraction and even heroism of the terrorist’s sacrifice, as he did its manifestation among the militants of his time, but he would have tried to demonstrate that its most sublime form lay in nonviolence. However, this could only be done by linking sacrifice to what was politically possible.

One way in which the heroism of sacrifice can be made politically salient is by rendering oneself invulnerable to feelings of horror at the sight of suffering and the imperative to action it provoked. This also entails remaining indifferent or rather stoical about the kind of suffering over which one has no control. Such an attitude was, of course, implicit in Gandhi’s idea of resigning responsibility to others. It is an attitude that goes completely against the expansionary and even imperialistic spirit of humanitarianism, which he, like Arendt, thought only encouraged violence of various kinds. The Mahatma always maintained that the responsibility for one’s neighbor’s suffering took precedence over that of more distant victims. He was also highly critical of industrial technology — for instance, the railways — which permitted people to escape their neighbors and localities and to imagine a false identification with abstractions like humanity.

Martyrs and Muslims

It is neither possible nor desirable to return to a time before globalization, as far-right nationalists and others would like to do. But refusing an abstract identification with global entities like humanity, or the Muslim community that militants claim represents its victimization, is crucial to recovering the capacity for politics. Just as Gandhi rejected the idea of humanity as a project, so too might Muslims today refuse that of the Muslim ummah, if they are to do anything more than squabble with militants about theological semantics.

Tunisia’s Ennahda, the only successful Islamist party in the Arab world, has recently done just this after taking power in that country through the only successful revolution of the Arab Spring. Ennahda’s leader, Rachid Ghannouchi, seems to have realized that militant outfits like Al-Qaeda and ISIS have stolen radicalism and thus global influence from older Islamist groups like his own, and that the traditional resort to Pan-Islamic activism has, at the same time, become dangerous and meaningless. Ghannouchi has therefore forsaken the internationalism of the Muslim Brotherhood, as well as the global mission of terrorism, to define his Islam in purely Tunisian — which is to say, political — terms, hoping that this serves as an example for others in the region and beyond.

And in Dhaka we saw even more remarkable instances of such repudiation, when a number of Muslim hostages at the Holey Artisanal Bakery refused to identify with Islam and save their lives. A Bangladeshi-American student named Faraaz Hossain is being celebrated on social media for refusing to abandon his friends and dying alongside them, though he had apparently recited enough scripture to be freed by the terrorists. Even more interesting is the case of Ishrat Akhond, a young woman who refused even to identify herself as Muslim and court release. Here was a truly Gandhian sacrifice, one demonstrating its superiority to the one exercised by the militants. For Ishrat Akhond abjured Islam itself as a global identity and mission, and in doing so recovered her particularity as a Muslim.