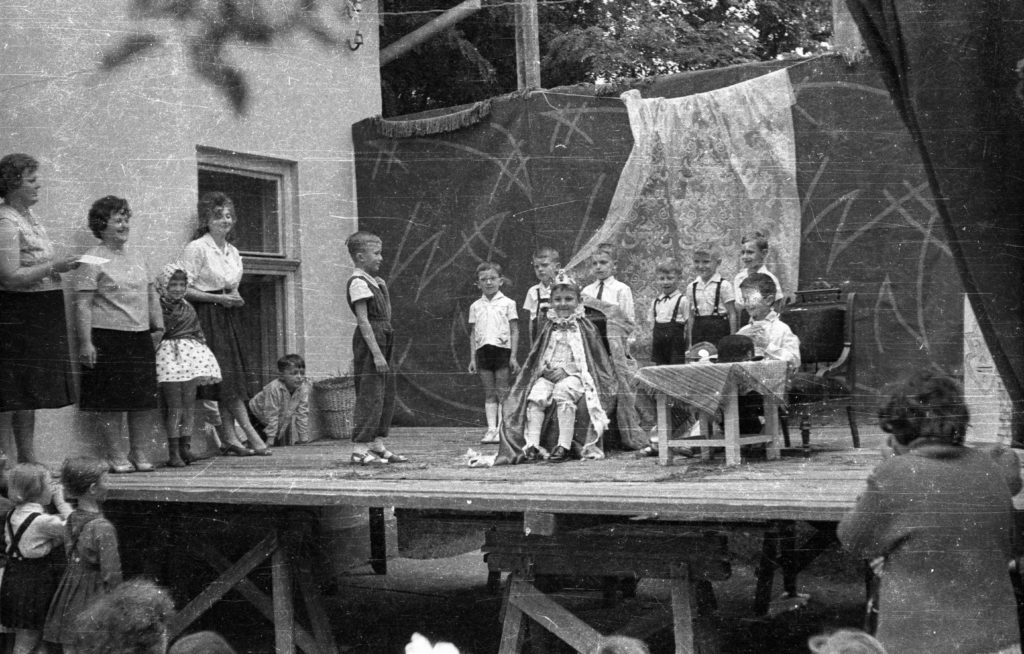

The first time script I ever read was Bram Stoker’s Dracula, as adapted by Hamilton Deane and John L. Balderston. I played the role of the Count himself in my Catholic high school production back in 2001. The production was about what you would expect out of a group of American teenagers pretending to be European adults. I was mortified when, as I stood on stage during the final dress rehearsal in my dopey cape and fangs and white face paint, watching as the actress playing Mina asked — as politely as she could — if we could please change the scene at the end of Act One where Dracula kisses Mina on the lips. We’d rehearsed it a dozen times already, always stopping just short of the kiss, which, as a bookish teenager in the theater club was about as close to girls as I generally got. The director looked at my co-star, registering her shame and terror, and conceded. Perhaps, he suggested, Dracula could kiss her on the neck? No, that wouldn’t work. Perhaps bite her neck….? She hadn’t even stopped shaking her head. “Okay, he can start to bite your neck, but we’ll drop the curtain before he makes contact. How’s that?” The actress winced, then gave a deep shuddery sigh and nodded, eyes locked in a thousand-yard stare. A true professional. In the end, the scene played out much as Mr. Stoker had surely imagined it, with a 17-year-old Count Dracula almost maybe probably going to bite the neck of a noticeably grossed-out Mina. The scene was taught, real, and very powerful.

Ultimately, the experience made me realize that I lacked the basic skills necessary to be a capable performer (i.e., confidence, grace, a good speaking voice, and that magical ability to make people want to look at you); however, I managed to come away with a deep and abiding love of plays — writing them, watching them, and, of course, reading them.

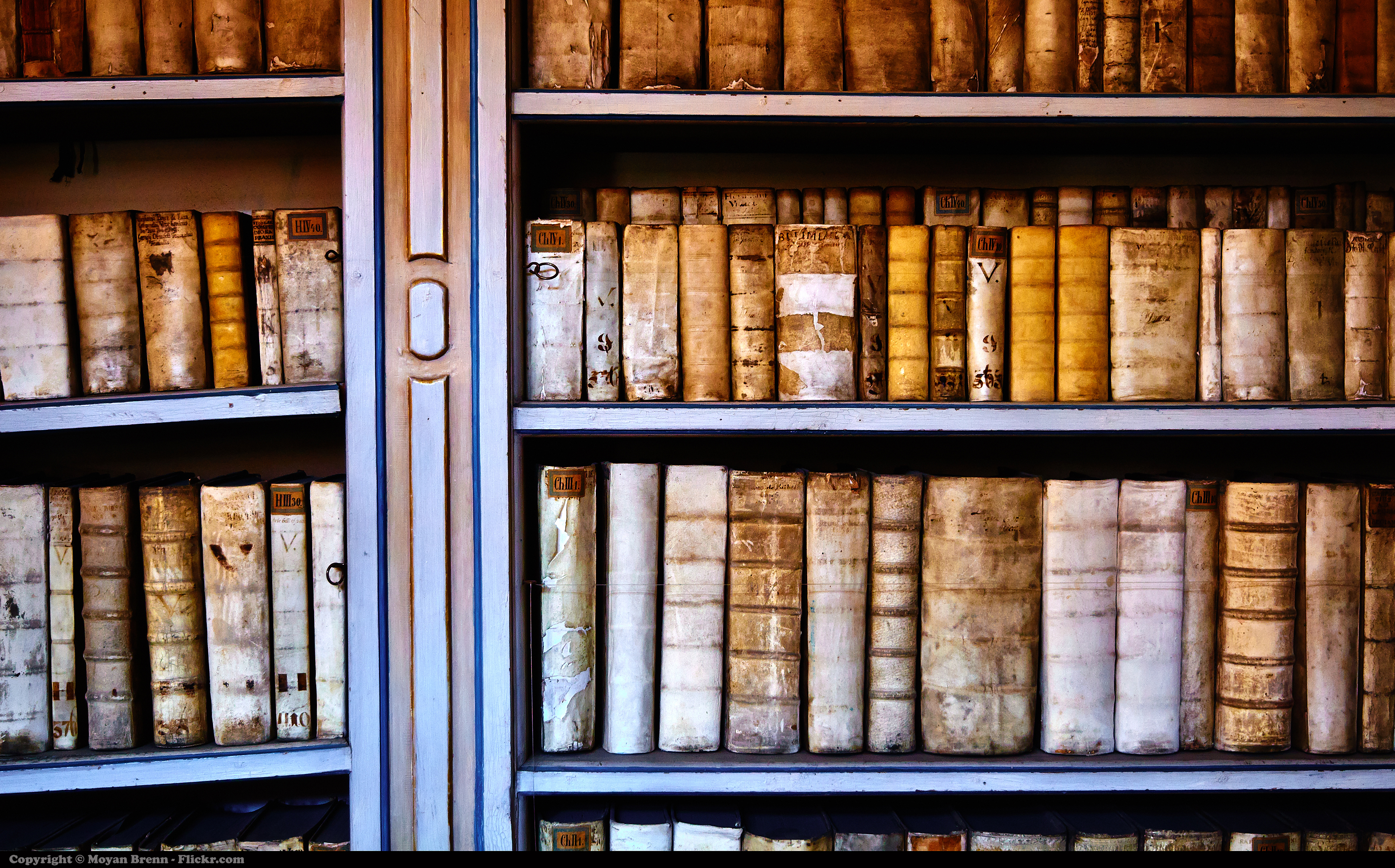

Yes, there’s something a little strange about reading plays — they tend to be pretty talky, comparatively slow-paced, and require the reader to do much of the heavy lifting in terms of imagining how the scene actually looks and moves. But there’s also a special joy to reading plays that you’re not going to find in a novel, short story collection, or book of poems. At their best, plays marry the probing characterizations of a novel with the rich language of poetry — so much so that it’s become common practice for playwrights to break up their dialogue into fragmented stanzas. And then there’s the time element: because plays are intended for performance, brevity is generally of, at least, some importance. Creatively-speaking, this tends to force the work to find its narrative and linguistic essence, which heightens the poetic effect. Practically, it means that plays make for quick reads. Even very long scripts like Angels In America and The Kentucky Cycle are shorter than most novels, and the vast majority of plays fall somewhere between 12,000 and 20,000 words — roughly the length of a short story — and can be read in an hour or so. This always struck me as a nice solution for all the people who complain (usually around the new year) that they really wish they read more.

Still, there’s some debate about reading plays — particularly between playwrights themselves. Sam Shepard said in a 1996 New York Times interview that “The play is only a blueprint for the production,” a common argument for the primacy of performance. In his 2004 essay “Read Plays?” Edward Albee argued more or less the opposite: “Plays…are literature, and while they are accessible to most people through performance, they are complete experiences without it.” And then there’s Wallace Shawn, whose essay “Reading Plays” represents a kind of sensible middle-zone: “It is strange, then, to isolate the dialogue of a play in a book, and it’s strange to read it — to sit somewhere alone and read it silently to yourself. Reading a recipe is not the same as eating a cake. Reading about love-making is not the same as making love. And yet, on the other hand, one has to say that a written play can have a special magic of it’s own.”

I would argue that they’re all right, and that whether or not a script represents a “complete experience,” has mostly to do with what play you happen to be reading. Albee, for instance, was famous for the dictatorial level of control he exerted over productions, and this is reflected in his scripts, which are full of detailed instructions to the actors, not only on where to pause and for how many seconds, but also how to perform their lines. Flipping to a random section of The Goat, I see nine of the eleven lines of dialogue on that page paired with parenthetical directives like “Slow; deliberate,” and “Grotesque enthusiam.” Compare this to the work of Mac Wellman who will frequently include stage directions like “Something strange happens…” leaving what that might be up to each individual production and reader to decide for themselves. It quickly becomes clear that not all plays are designed to be read the same way.

When weighing the merits of seeing plays versus reading plays we are often comparing the reading experience to an ideal performance, which obviously isn’t always the case. There is simply nothing worse than seeing a bad play (bad stand-up comedy runs a close second). How does one prepare, psychologically and spiritually, for a high school production of Guys And Dolls or Damn Yankees? One doesn’t. (I can speak from experience — I acted in these productions as well.) The magic of theater hinges on an audience’s willingness to pretend that the actors they’re looking at can’t look back, and that the moonlight spilling through the window is being caused by, well, the moon, and not those giant black lights hanging from ceiling. Strip away that suspension of disbelief (it doesn’t take much) and suddenly, the play feels less like art or even entertainment, and more like some excruciating endurance test wherein time slows and every line belted out by an actor feels like a knife in your heart, because what you really want to do is go up on stage, stop the show, give everyone involved a hug, and tell them that while it didn’t work out so well this time, next time will be better, so how about we all just go home. In such a case, reading really is the way to go. I’ve seen three productions of Edward Albee’s The Goat, and while all had their virtues, I really can’t say that any of them equaled the experience I felt the first time I read the script. The flip side of this would be Thorton Wilder’s Our Town, a play I read in college and which struck me at the time as rather saccharine. Some years later, I was lucky enough to see David Cromer’s masterful production at The Barrow Street Theatre in New York (and then again, the following year, when it moved to Boston) and the play was revealed to me in a way it hadn’t been on the page, and I spent the better part of two hours in a puddle of tears, spellbound by the majesty of a script that I’d long since written off.

But of course, none of these factors really matter if you can’t afford to see a play in the first place, and given the cost of tickets these days, that’s a reality that many of us face. Broadway musicals are notoriously expensive, averaging around $100 a pop, and often times going for as much as $500 for front row seats. Even smaller off-Broadway productions (which is arguably where serious theater lives these days) frequently cost around $65 a seat — over four times as much as a movie ticket. Most major theaters have Student or “Under 30” memberships, as well as ties to various discounting websites, like Goldstar. Nevertheless, the finances surrounding live theater remain largely exclusionary, which is a shame, because there are powerful tales being told by masterful storytellers, and it would be a bummer to think that large swaths of the public won’t get to experience them because they don’t live in a major city, are over 30, or don’t have an extra $130 bucks to spend on a Friday night. Bear in mind, this isn’t me railing against the theaters themselves — plays are expensive to produce (especially for the rare company that aspires to pay their actors a decent, if not livable, wage) and their audiences are extremely finite. But it doesn’t change the fact that many people’s access to the medium is quite limited. Which brings us back to reading them, and given the vast number of diverse playwrights working today, there’s quite literally something for everyone.

Into Stephen King novels? Check out The Weird or The Velvet Sky by Roberto Aguirre-Sacasa (who adapted Stephen King’s The Stand for Marvel Comics), or Something in the Basement by Don Nigro, or The Humans by Stephen Karam, a powerful, slow-burn chiller that recently won the Tony award for Best Play.

Like Ex Machina-esque mind-bending sci-fi movies? Read The Nether by Jennifer Haley, or Stone Cold Dead Serious by Adam Rapp. Both use speculative technology as a way of exploring what it means to be human.

How about Southern gothic meditations on evil, à la Flannery O’Connor and Cormac McCarthy? In that case, take a look at The Jacksonian by Beth Henley, The Glory Of Living by Rebecca Gilman, Killer Joe by Tracy Letts, or Bash by Neil Labute (which is more of a Utah-Gothic, but still fits snugly into the sub-genre).

For fans of literary dysfunctional families, à la The Corrections, oh man, do we have you covered: There’s Topdog/Underdog by Suzan-Lori Parks, The Goat by Edward Albee The Brother Sister Plays by Tarell Alvin McCranney, and Housebreaking by Jakob Holder, a searing, darkly-funny drama, and one of my personal favorites on this list; a hidden gem of the American theater (Artistic directors, take note).

For fans of postmodern fiction (i.e. Pynchon, DeLillo, Barthalme, et al.) your theatrical allies are going to be Erik Ehn (The Saint Plays), Mac Wellman (Sincerity Forever), Jeffrey M. Jones (Seventy Scenes of Halloween), Len Jenkins (Dark Ride), and María Irene Fornés (Mud). Weird, wonderful, challenging playwrights all.

And if all of this is sounding a little heavy, here are a few comedies worth taking a peak at: The Big Slam by Bill Corbett, The Realistic Joneses by Will Eno, The Aliens by Annie Baker, and Becky Shaw by Gina Gionfriddo.

And all of this is to say nothing of the classics, which I’ll save for another essay.

Last spring, I worked as an adjudicator for an artist residency and found myself working through a pile of over 220 submissions by authors, playwrights, screenwriters, essayists, and poets. Like all writers, I started as a reader; however, it had been a while since I’d read any contemporary poetry. The three months I spent reading poetry submissions reminded me not only what I love about the medium itself, but the importance of periodically mixing up your cultural intake. I’ve developed certain expectations when it comes to fiction, theater, and film, that I haven’t with other art forms, and so the poems contained strange, new surprises that I hadn’t expected. Everything about them felt new and raw and interesting, and I found myself connecting with them in a way that was, at times, startlingly intimate. In a very real way, they reminded me why I love to read, and I’ve spent the past few months blind-buying poetry collections off the shelf.

Often times, cultural participation is discussed as a kind of race — “Have you seen the latest episode of [insert much-hyped television show]?” or “Have you read the latest book by that [insert critically-lauded author]?” — as though consuming art is somehow a competition. And while there’s certainly a good argument to be made in favor of reading deeply (as opposed to widely), I’ve noticed that the people who engage in this kind of cultural Keeping-Up-With-The-Jones simply seem to enjoy things less. This strikes me as the best reason to read — if not a play then at least something new. At worst, it’ll tell you something you didn’t know about your usual reading. At best, it’ll tell you something you didn’t know about yourself.