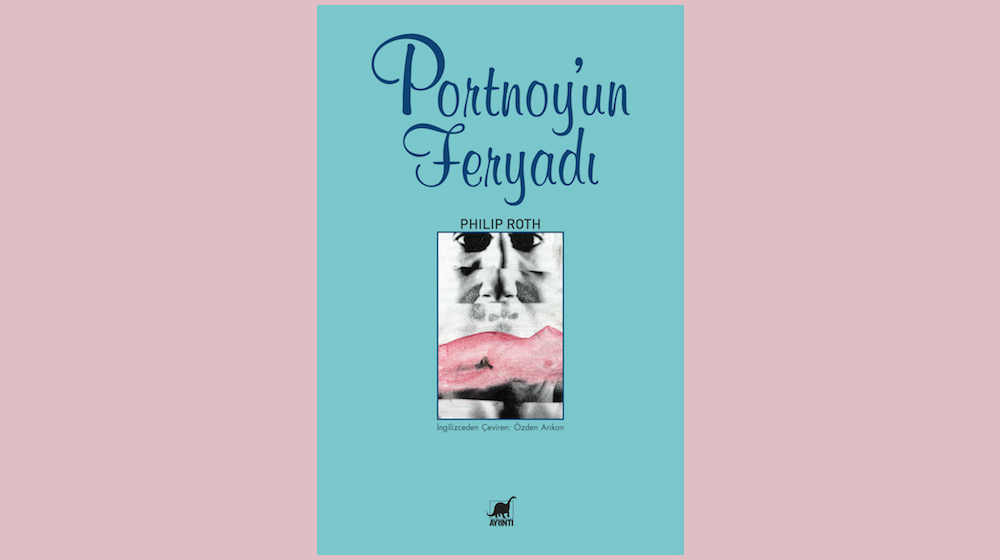

The Turkish edition of Philip Roth’s Portnoy’s Complaint was published in 1999. Shortly after, a Turkish prosecutor summoned the book’s translator and publisher to his Istanbul office. Apparently, a dutiful citizen had reported the book to a government body known as the “Board for the Protection of Minors Against Harmful Publications.” The prosecutor asked Özden Arıkan, Roth’s translator, and Ömer Faruk of Ayrıntı Publishing House, whether Alexander Portnoy’s confessions could be considered a violation of Turkish morality. They pleaded not guilty.

The prosecutor sent a copy of Portnoy’s Complaint to Istanbul University’s Turkish Literature Department, staffed mostly by nationalists and conservatives, to get an “expert report.” The report’s findings agreed with the Board’s verdict, and for two years Turkey joined Australia and many American libraries in banning Roth’s 1969 novel for its sexually explicit and supposed morally corrupt content. The police visited the publisher and took all copies of the book into custody. Meanwhile, bookstores took down copies on their own to escape confiscation.

The court case of Portnoy’s Complaint took place at Istanbul’s Penal Court No. 2. Arıkan attended the first two court sessions, but she was in the process of relocating to Germany, and missed the third. In the end, the prosecutor, busy with prosecuting more explicitly political books, decided to drop the case, and on March 20, 2001, the Istanbul Penal Court No. 2 acquitted the translator and publisher. Ayrıntı proudly republished the book with a sticker on its cover announcing the legal victory.

“I don’t know another book I have enjoyed translating that much,” Arıkan, who continues to work as a translator, told me. “I would be upset when I had to go to sleep at night, or rather, early morning. I would run to my desk to resume my work as soon as possible the next day. Even once a neighbor I met at the hallway asked me why I was laughing out that loud at 3 a.m.”

Portnoy’s Complaint was the first Philip Roth book I bought. Its legal victory in Turkey made the book all the more appealing. In the early 2000s, Turkish courts preferred to ban books on moral grounds. Nowadays, there are dozens of journalists in Turkish jails accused of “terrorist propaganda.” In 2010, when I was asked to translate Roth’s Everyman into Turkish, I was reminded of government censors. Roth’s late style — the sentences that ebb and flow as they describe the unnamed protagonist’s childhood — gave me a hard time. When I filed the translation, my publisher said Roth wanted to take a look. I imagined him poring over his meditation on death in my Turkish.

When it appeared in the winter of 2011, elderly Turkish critics wrote approvingly of Everyman, admiring the melancholy tone of the swan song. Nobody called it a masterpiece, and I noticed how people continued to associate Roth with Portnoy’s Complaint. But how could I complain? No dutiful citizen reported my translation to the Turkish government.