You have gone for a visit to an attractive place. Your hosts are initially friendly and solicitous, but after a while you notice disturbing changes in their behavior. One day, they seize you, confine you in a small room, and curtly inform you about what is going to happen. Tomorrow you will be given a gun, ordered to point it at a particular part of your body and pull the trigger. The gun has a very large number of chambers, most of which are occupied by bullets of varying degrees of destructiveness. You will be allowed to spin, and thus determine which chamber is active, before you shoot — but you will not know in advance what the chamber contains. You will also draw a card to decide on the anatomical region at which you must aim. Some of the cards specify shots that would be fatal, selecting your temples or the roof of your mouth or the chest above your heart. Others are more forgiving, allowing you to escape with paralysis (the lower spine), or the loss of a leg, or damage to the little finger of your non-dominant hand. A few let you point the gun in whatever direction you choose and to fire harmlessly out of the window.

You are, understandably, terrified, and you plead for mercy. Your captors consider, and offer you a deal. The date for this event is to be postponed. In the intervening period, you will continue to live as you did before, but under significant restrictions. You will be closely monitored, and subject to a list of rules. Some of these rules demand changes in behavior you find inconvenient and irksome, but, under the circumstances, tolerable. Others require large modifications of your way of life. Ordinarily, you would protest having to conform to them. But, you are told, your conduct between now and the new time for the shooting will determine the state of the gun and the composition of the deck from which you will have to draw. Go on as you have previously done, and the percentage of chambers occupied by bullets will increase, the destructive power of the bullets will be greater, and cards specifying vital organs will be substituted for the relatively harmless ones. On the other hand, to the extent that you abide by the rules, the threat posed by the gun will be diminished (some bullets will be removed, less powerful replacements will be inserted in place of others), and the deck will be changed to increase your chances of survival. Once you have pulled the trigger in accordance with the conditions of the game, if you remain alive, you will be permitted to go free, living the rest of your life in whatever shape you can.

What would you do?

Watching the democratic candidates for president debate with one another prompted me to imagine this scenario. One candidate, Governor Jay Inslee, has made addressing climate change his first priority. When he speaks about the issue — as with Barack Obama on race, or Elizabeth Warren on protecting consumers — there is a truly satisfying sense of real expertise. Here is someone who has probed deeply, someone who genuinely understands, and who has taken great pains to master the details. Surely, other candidates favor policies that might help our species cope with this enormous problem. Perhaps they are also well-informed about the threats to the human future, and what might be done to avert them. Nevertheless, in their public presentations they don’t reveal the same depth of knowledge as Governor Inslee.

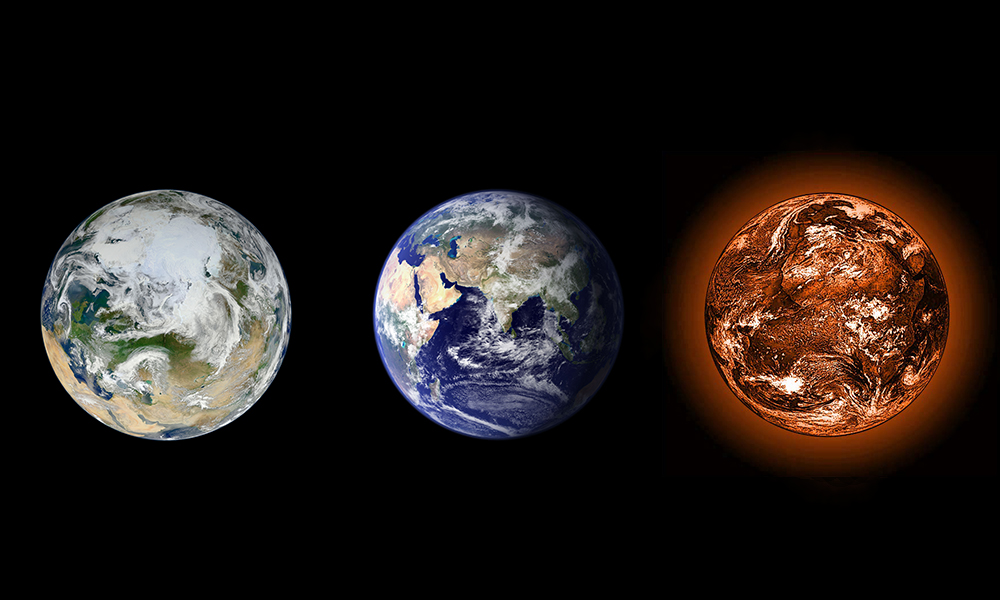

Despite his mastery of climate issues, the Governor made a single misstep, falling into the rhetorical trap of framing the question in black and white. We must act now, he declared, before it is too late. Too late for what? Like many others concerned with the warming of our planet, he conjured a coming apocalypse. The alarm bell rang, delivering a message. “This election is critical. Elect me and all will be safe. Elect someone else and human life on this planet is doomed.” That message is conceptually wrong. We are not confronting an either-or situation, where one route leads to bliss and the other to disaster. It is all a matter of chances — unknown and sometimes unknowable chances, and uncertainties.

My imaginary version of Russian roulette captures the actual predicament — although it could be refined to allow different guns and different decks to people living in different societies and in different regions of the world. Governor Inslee might rightly portray himself as someone so committed to following the rules prescribed by the captors that he would obtain the maximally favorable conditions when the trigger actually has to be pulled. The Trump administration, by contrast, revels in adding as many high-velocity bullets and as many fatal cards as it can. Where the other democratic candidates stand is typically unclear: some of them, perhaps, are as committed as Governor Inslee. But not all. Vice President Biden’s remarks indicate that he has only a vague understanding of the severity of the problem. Although in 2015 securing international cooperation on a limited set of targets was an encouraging first step, a return to Paris now would be far too little — and too late.

People who pooh-pooh warnings about climate and the human future will continue to cry “Alarmist” when the situation is more accurately characterized in probabilistic terms. They will dismiss the analogy. That, however, is a mistake, born of misunderstanding of the character of the threats we face. For too long, discussions of climate focused on averages: how much will the sea rise by 2100? (Not, of course, that the end of this century has any magical significance.) The experiences of recent years have brought home the greater impact of extreme events: what matters isn’t the average but the greater frequency of events at the tail of the distribution and the occurrence of new outliers as the average shifts. Even when that is understood, however, the further effects remain unappreciated.

When the rains don’t come as expected, the sources of water disappear, the crops wither — and people are forced to move. By the time they do so, they are often malnourished and deprived of opportunities for maintaining personal hygiene. Changing ecological conditions open up new channels for the spread of disease — as well as opportunities for the emergence of new diseases. Migrating populations are vulnerable to infectious disease, and, of course, they spread disease in the communities they attempt to enter. A planet battered by storms, floods, fires, and droughts will be one in which huge populations will be forced to leave their homes. To anyone who thinks (quite reasonably) that our world already faces a migration crisis, so-called Alarmists have a simple reply: You ain’t seen nuthin’ yet.

Once it’s recognized that there are potentially many ways in which sequences of extreme events can interact with human behavior, it should be clear that, given what our species has already done, the gun contains deadly bullets in some of its chambers. The frequency is unknowable, but the probability of spinning a live bullet and drawing a fatal card can’t be dismissed as negligible. Moreover, there are plenty of ways in which the lives of our descendants can be crippled and diminished. In these respects, the analogy is sound.

Not in all, however. I’ve simplified by imagining a single subject — Humanity — that suffers a single fate. A more accurate version of my story would recognize a large variety of people who are given different guns and draw cards from different decks. Some of them are lucky: many of their chambers are bullet-free, and the likely cards don’t target vital organs. Others are correspondingly unfortunate. Furthermore, the burdens imposed by following the rules are far greater in some instances than in others. Those who live in particular strata of particular societies can adapt more readily to the project of making the eventual trigger-pulling go better.

So revised, the scenario responds to an insight of other Democratic presidential candidates, those who center their campaigns on remedying the vast inequalities within and among societies. Following the rules — acting to decrease the impact of climate change — affects different groups of people very differently. Justice demands that the burdens be distributed fairly. That means redistributing resources so that the few are not given a virtually unloaded gun and a benign deck, while the many are correspondingly doomed. Properly understood, the policies Governor Inslee demands go hand in hand with the commitment to fairness and the reduction of inequality so eloquently expressed by some of his rivals, Senator Warren foremost among them. The Green New Deal is not some radical fantasy. It’s an urgent necessity.

So, what should you do?

Philip Kitcher, John Dewey Professor of Philosophy at Columbia, is the co-author (with Evelyn Fox Keller) of The Seasons Alter: How to Save our Planet in Six Acts.