As many readers will be aware, there have been serious gains made by marginalized writers over the last generation. In recent times, initiatives like the Stella Count and VIDA Count have made the presence of women and non-binary writers more visible in both Australia and the United States. Together, both Counts hold literary journals to account by calculating authorial representation as a proportion of total publication over the course of a year. The Stella Count in 2018, for example, reported that the Australian Book Review had 41% reviews of books authored by women compared to 71% in Books + Publishing.

The Stella does not, as far as I am aware, consider non-binary identity. In Australia, I know there have been discussions of undertaking a count of authors who are people of color and/or Indigenous. These initiatives are critical interventions to begin aggregating data on the gender and race prejudice of journals. Some journals seem to have taken notice, perhaps by simply seeing their unconscious biases, taking these biases into account and wanting to do better. Some have improved over time, while others have clung to the sinking ship captained by the straight white man.

So far, these interventions have focused on journals, and only critique editors and other staff by implication. Thankfully — and probably most efficaciously — there has been little ad hominem confrontation. This institution-level method allows us to think about the structure, culture, and ecosystem of journals, which includes funding bodies and readers as well. It helps us call out pervasive inequalities, to highlight how entrenched prejudice can be, and to see that the answer is not to be found simply by replacing anyone in particular.

And yet, what is the responsibility of the individual in this decentralized method of critique? In asking that question, it raises the related one: what can an individual do?

By now, calls to decolonize reading lists are common enough. And the extent to which we can add thinking about ability, gender, location, language, and sexuality will certainly help us reach a more equitable point in research and storytelling. Sure, we can change what we read, but what happens if one is also a literary journalist? Should we boycott the publications we routinely contribute to because the editorial direction remains misogynist or racist, if only structurally and subconsciously? The answer to that question is surely up to individual writers, and anyone who plies their trade in this industry deserves to be treated with a careful sense of respect in the choices they make. But for me, confronting these questions meant reflecting on my writing to see where my own unconscious biases are. In that effort, I made these graphs about my writing on contemporary literature:

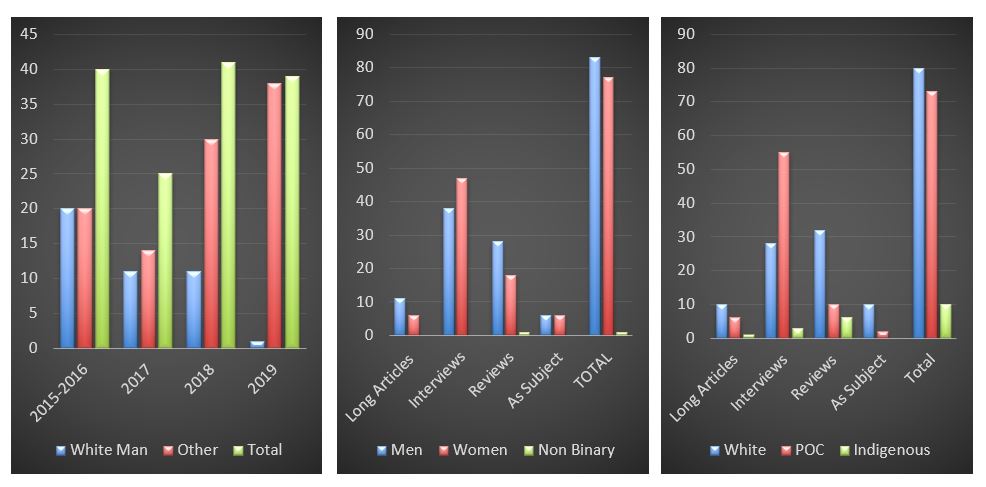

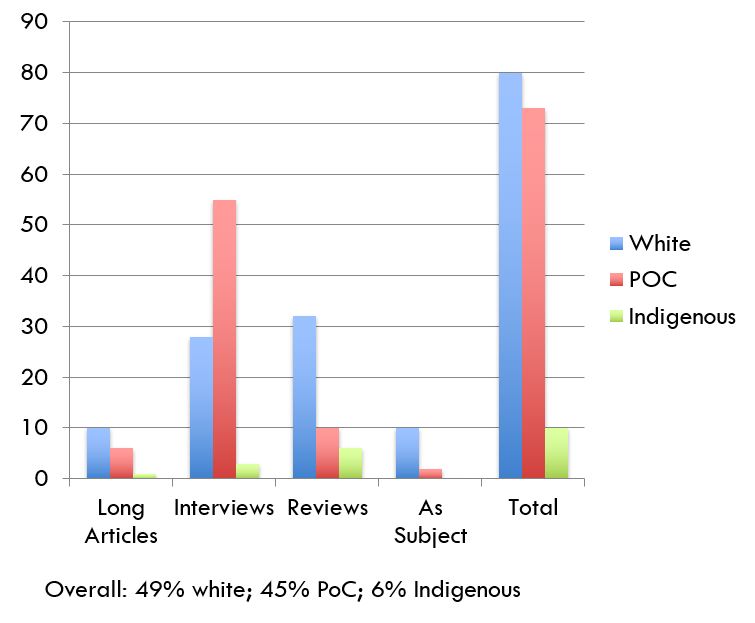

There are a few conclusions other literary journalists can draw from these. The first is the exercise itself, which helped me to reflect on where I had come from and what I need to do. In the first graph, you can see that I have written about, reviewed, or interviewed white men only 29% of the time. While the percentage of white male representation would rise considerably if I were to include writing about “the classics,” which I undertook over the course of 30 articles or so for Cultural Weekly a couple of years ago, by following the Stella Count criteria, I only included writing on contemporary literature. What might also be interesting to note about the first graph is that the percentage of white men has gradually decreased over time from 50% in 2015-16 to 44% in 2017 to 27% in 2018 to 3% in 2019. I attribute this trend to having gained more writing autonomy over the years, and also to coming into a greater consciousness of my community and myself. When I began writing about four years ago, I routinely accepted the books I was asked to review or the editorial direction that was asked of me. Over time I acquired the ability to select and promote writing and writers I think are worthy. If that means recognizing one’s own complicity at the start, it also means working towards a position that better suits one’s identity and ideology as one grows more confident and established.

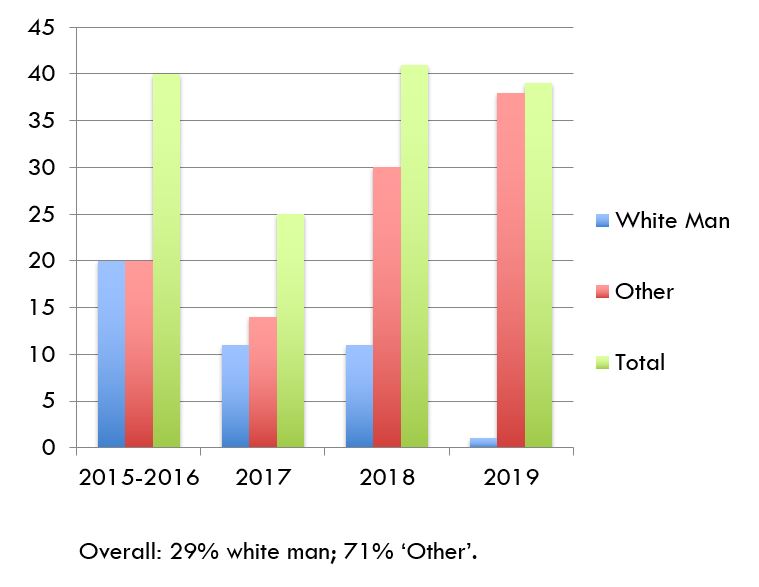

As for the second graph, this represents gender proportion over time. 65% of my long articles have been about men compared to 61% of reviews and 45% of interviews. 50% of the writing about me has come from men and 50% from women. To my knowledge, I have only reviewed one non-binary author, and no non-binary person has reviewed or interviewed me. I have written about men 52% of the time, women 48%, and non-binary people less than 1%.

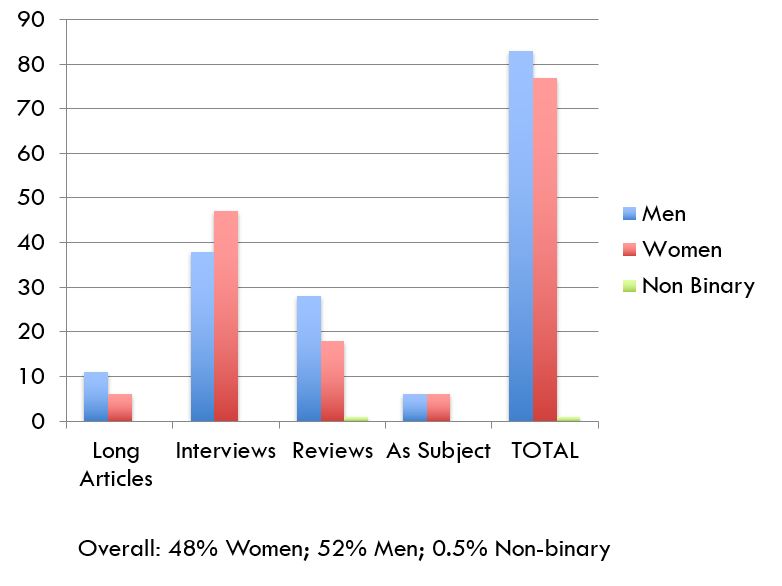

The third graph represents race proportion over time and by gender. 59% of my long articles have been on white writers compared to 67% of reviews and 33% of interviews. 83% of the writing about me has come from white people. The total as you can see is that I have written about white people 49% of the time, people of color 45%, and Indigenous people 6%.

These metrics about my contemporary literary journalism might also be relevant to how I situate myself in the wider literary ecosystem. I am a Malayali person, yet I am also aware of being mixed, which includes a white heritage; I do write as a straight man who is privileged by education, class, status, location, language, and other valences of identity. In thinking through the kinds of data I tabulated, it might be enough to encourage other writers to conduct their own Stella or VIDA Counts, but we might also think about the entrenched structures that make it harder to get a start if you want to write about your community and how there are few opportunities to do so unless you starts a journal yourself.

When I compare 2015 to 2019 in terms of what I felt I was allowed — let alone encouraged — to write by editors, I realize that I relied on my authorial identity as a passing white man to meet normalized expectations. In the desire for equity, though, it is about increasing the visibility, presence, and importance of women, non-binary, PoC, Indigenous, and Other writers. This is not only because it truly represents the lived diversity of our contemporary societies and the world at large — that would have us hope to simply meet our demographic fair share. Rather, it is also importantly about the responsibility, obligation, and pleasure to be gained from reparative criticism, including that of literary journalists themselves. We journalists ought to exceed expectations and make space for the marginalized in a more complete manner. This is about the return of cultural capital through networks that have often excluded Others, all in the name of furthering work that is beautiful, intelligent, and as good as anything else. It is important to account for what has happened in one’s own practice in order to work towards something better. Doing a count for yourself might be a good place to start.