At two a.m. I get out of bed and check what the long-legged buzzard is doing. Unlike me, she’s sleeping, her head tucked under one wing. Everything is so still, I wonder if the webcam is working, so I lean into the screen and notice the buzzard’s feathers ruffling slightly and a few emerald rock plants, close to the nest, rippling as though underwater. I read through a sheaf of papers on my desk, translations of poems I’ve been working on this week. Now the buzzard is looking straight at me, her eyes luminous in the dark, her hooked beak slightly open. From time to time she inclines her head, listening to the distant howling of a coyote.

She blinks.

I blink back in the darkened space of my office.

The wind whistles through the night.

Then I check the donkeys in the Safe Haven Sanctuary, a rescue center for animals from Israel and the Palestinian territories. The webcam is set over the trough, and tonight there are three donkeys in the frame, one white and two brown, their soft necks dipping down into the fodder, their tails swinging. A fourth donkey rests nearby on the straw-strewn floor. They typically sleep standing up, although I’ve heard donkeys sometimes sleep in a sitting position when they feel secure.

I like being the only person awake, the house to myself; this past year has made me appreciate these small moments of tranquility. The quiet house, the occasional creak of a crack in a wall, the sound of my own breath.

The sharp cry of the buzzard cuts through my earbuds. Something has startled her outside of the frame, and she stretches her neck and flies off. The wind whips up again, and outside my window the branches of the terebinth tree begin to dance.

¤

I became interested in animal and bird webcams during the second lockdown. They’ve become my soundtrack when working, blocking out sounds from my own habitat, and a gentle diversion when I need a break.

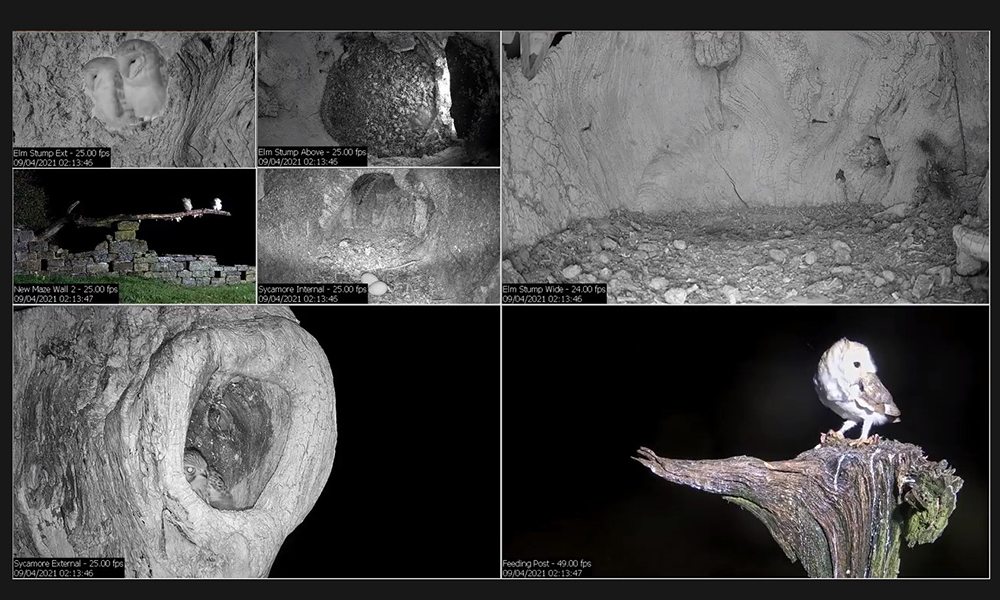

I follow the CritterCam of racoons, deer, and even an alligator in a backyard of North Carolina, and Barn Owls, Kestrels & Other British Wildlife in the UK, along with thousands of other people from all over the world who are drawn to these creatures.

It’s these parallel lives I find so fascinating. They have their own rhythm, and they have patience, something I’m still learning. Often nothing happens for hours and hours, but still there’s comfort in watching these creatures go about their daily lives, the owls tending their nest, flying off to look for prey, and the donkeys back at the sanctuary, jostling at the trough, standing by the barn door, nuzzling up against each other.

It’s addictive, although most of the time nothing much happens.

Years ago, a buzzard crashed into my living room through the open French windows. We’d recently built the house on the edge of the Ella Valley, close to the forest. I’d always imagined birds of prey as huge creatures; this buzzard was no more than 20 inches in length, although in flight it has a wingspan of around 50 inches. In its talons, the buzzard held three-quarters of a bloody mouse. It was hard to tell who was the most shocked: the buzzard who had taken a wrong turn, or me. The mouse hung upside down, quivering, probably dead already. Back then, no one believed us.

The Ella Valley sits on the slopes of the Judean Hills. We still reminisce about the deer we used to see roaming the area, and the porcupines who rose up alarmingly on their hind legs when startled by the headlights of cars at night. As building continues to take over stretches of land, these are rare sights today, but I’ve seen raptors circling above the valley, their wings outstretched, or perched on treetops in the forest. They’re usually in couples; when I see one, I know the mate is somewhere close by.

Long legged buzzards can be found in parts of Europe, the Middle East, Northern Africa, and Asia. They eat mostly rodents, but also small birds, lizards, and insects. The location of this particular Raptor Nest Cam is kept secret in order to protect the birds from overzealous humans. The nest rests on a narrow shelf of pale limestone, evidently high up on a cliff, because last year I watched the fledglings learning to fly there. I even saw one fanning his wings determinedly, revealing speckled white feathers in a magnificent V, before taking off into the sky.

In the late morning, the buzzard stands up, shifts position, and settles down again. A fly hums around the nest. Last month, the female laid two white eggs speckled with brown. Whenever she flies off, I wonder whether it’s wise to leave those eggs so exposed, even briefly. Last year, an eagle owl swooped down in the middle of the night and snatched away one of the fledglings. This particular incident is available for viewers to see on the Raptors Nest Facebook page, which has 28,000 followers.

The tawny owl in Yorkshire, affectionately named Luna by the webcam owner, also laid two eggs last month in the stump of a beech tree. On a recent chat with other owl enthusiasts, I learned she spends twenty-three hours a day in the nest, with only brief forays away. Her mate, Bomber, delivers her food offerings. I watch Luna, motionless except for her head, which occasionally rotates from side to side. Finally, she twizzles her head briefly in the direction of the camera, and struts purposefully out of the beech stump. Another camera is trained on Gylfie and Finn, two adorable barn owls who can usually be seen leaning amicably against each other, dozing through the day.

Later that afternoon, I take a break and wander into the kitchen for a cup of coffee. My father calls me into his room, which overlooks the backyard. He lifts a finger to his lips and gestures in the direction of the pecan tree we planted more than twenty years ago. Hammering away at the trunk of the tree is a woodpecker. We watch it in silence for a few moments and suddenly there’s a cry in the air as another woodpecker soars over the tree and they disappear from the frame.

Top image from feed maintained by Robert E Fuller.