When my father died, in 1976, he had lived his allotted three score and ten years, plus two more. Two years and two months more to the day, to be precise. Six months before his death he looked like he would go on for decades. Then that February, a persistent cough led to the discovery of an enveloping mass around his lungs that was impossible to resect. On a hot August afternoon he rolled over to greet me when I walked into his hospital room and a minute later was dead in my arms.

Forty years later I still think of him many times a day: Wanting to have had more than 32 years with him; wishing he could have known the wonderful woman I married six years later and our two sterling sons; missing a conversation with advice as well as one of the long groaner jokes he loved to tell and told so well. And these days, I think of something else about him. On August 1, assuming that between now and then the bus with my name on it doesn’t stop to pick me up, I will have outlived him.

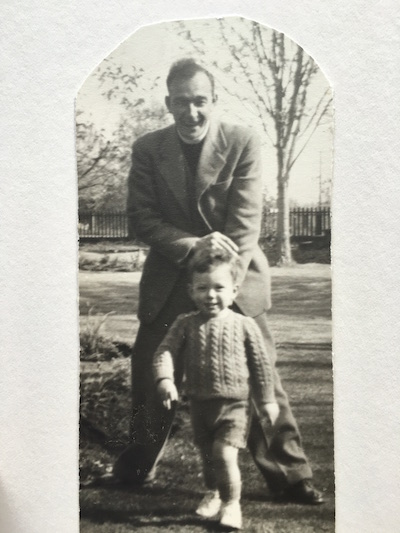

He was 40 when I was born and I saw it was not a drawback to have a father older than most, and so I was unconcerned that I was 42 and 45 when Simon and John were born. He taught me to love openly by telling me every day that he loved me, and he consistently demonstrated the bedrock importance of respecting others. Apart from the teenage periods when I felt he was completely clueless (I was amazed by how smart he got between my 17th and 18th birthdays), I hoped to be a lot like him and I measure myself and my abilities as a father and as a person against his, hoping to match them. For all those years he was ahead of me but soon he will be behind me. I’ll be the older with no more measurements against what he did at my then-current age.

He seemed immortal when I was a boy (for that matter, I thought I was immortal), and even for a while as the cancer consumed him it still seemed impossible that he would die, until suddenly it didn’t. By chance one day after the diagnosis, I reunited with a close friend since childhood on the M5 bus going down Fifth Avenue, a woman my father adored and who adored him as well, whom I had not seen in a couple of years. She invited me to dinner with her partner, a doctor. Over pasta and his exquisite red sauce, my friend and I reminisced about my father, all the while introducing him to someone new. We had drinks. We laughed a lot. Then midway through a sentence that I began in a light tone, tears erupted. “I don’t want him to die!” I wailed, and for the next 5 minutes I bawled and sniffled, unable to say more.

In the months after the surgery, optimism or disappointment—depending on the scans and X-rays—followed my father’s visits to the oncologist. In that time, we talked in bursts about our lives, catching up and filling in, saying what we wanted to say. I was with him the day after an appointment in mid-August. He asked me to answer the phone because his voice was weak from the chemotherapy. It was the doctor. His report was brief: the cancer had spread to the bones and there was nothing left to hope for, except an easy death. I struggled to keep tears at bay as I repeated the news to Dad. I told him I loved him very much and could not have had a better father. In an instant we had flipped roles; I was the father, offering succor. Then we flipped back. He was equally loving in reply but also remarkably calm, which stilled me. He was uncomplaining about his fate, I think in part because he had said some days before that life with the pain he felt wasn’t worth living, but also because, as an Episcopal priest with a deep understanding of and compassion for human frailty, he possessed abiding faith that there was something better ahead. He asked me to look out for my mother, and then, preferring pleasure to sorrow, suggested we get a beer and go outside to sit on a palisade overlooking the Pacific. I keep a picture in my office of him taken that afternoon, a broad smile on his face, a glass raised in salute. Two weeks later he was gone.

It is often said that one of the greatest lessons our parents can give us is how to die, and his grace carried to the end, as did my mother’s 20 years later through a torturous 2-year-long decline from ALS. Of course grace is something we hope to pass on to our kids in many ways, starting with how to live a life well. My sons are 26 and 29. I have not wondered much if or how they measure themselves against me or whether something I have done is a marker for them. (Although thinking on this, I am pretty sure that an evening involving a more than adequate sufficiency of Mai Tais at Trader Vic’s followed by jayrunning across a busy street is an experience they have resolved not to repeat with their teenage children.)

Many of us live in the shadow of our father. For some that shadow is an oppressive cloak that prevents us from either becoming or being seen for our own self. My father cast a long shadow but it at once sheltered me and offered a safe place to grow. His pride in any accomplishment I had was evident, even something as prosaic as growing taller than him. “A block off the old chip,” he would say. He looked a bit like the early film comedian Stan Laurel while my mother more resembled Ingrid Bergman. Sometimes he would add, “He has his mother’s looks, because I still have mine.” And I still have all he taught me as company for the mapless road ahead.