Earlier this month, Merriam-Webster announced that the word of the year for 2019 was “they,” noting that as a gender-neutral personal pronoun, they is increasingly used “to refer to one person whose gender identity is nonbinary.”

By now we’re used to skeptics wondering whether our modern culture has finally gone too far. How could the pronouns we’ve had for centuries suddenly be not good enough? My work as a literary scholar suggests that certain writers of previous generations might not be protesting the abandonment of linguistic traditions, but asking instead, what took you so long?

Others have pointed out that they has long been used in the singular when the subject’s gender is unknown, and that this usage goes back centuries. What few have realized, however, is that there were those in the past who experimented with pronouns because their own sense of gender identity was ambiguous, situated outside of accepted categories of male and female. In other words, the challenge of finding the right gender pronoun also has historical precedent.

In the 1884 French novel Monsieur Vénus by the writer Rachilde, the gender-bending protagonist Raoule de Vénérande maddens those around her not only by choosing fencing over more ladylike past times, but by refusing to settle on a pronoun.

“Let’s use ‘he’ or ‘she’ so that I don’t lose the little bit of sense I have left,” declares a frustrated suitor, after Raoule tries to explain that she loves “as a man.” “I always thought that I was one when I was really two,” she tells him. As she leaves the conversation dejected, for her friend has not really understood, she passes her aunt, a devout Catholic, and wonders, “Had anyone ever had the grace to pray for a change in sex?”

Rachilde, born Marguerite Eymery, claimed to have taken on her pseudonym during a séance in which she communed with the spirit of a 17th-century Swedish nobleman. But this, she later admitted, was a ruse. Her ambiguous new moniker was a way of freeing herself not only from her bewildered parents, but from the constraints of gender itself.

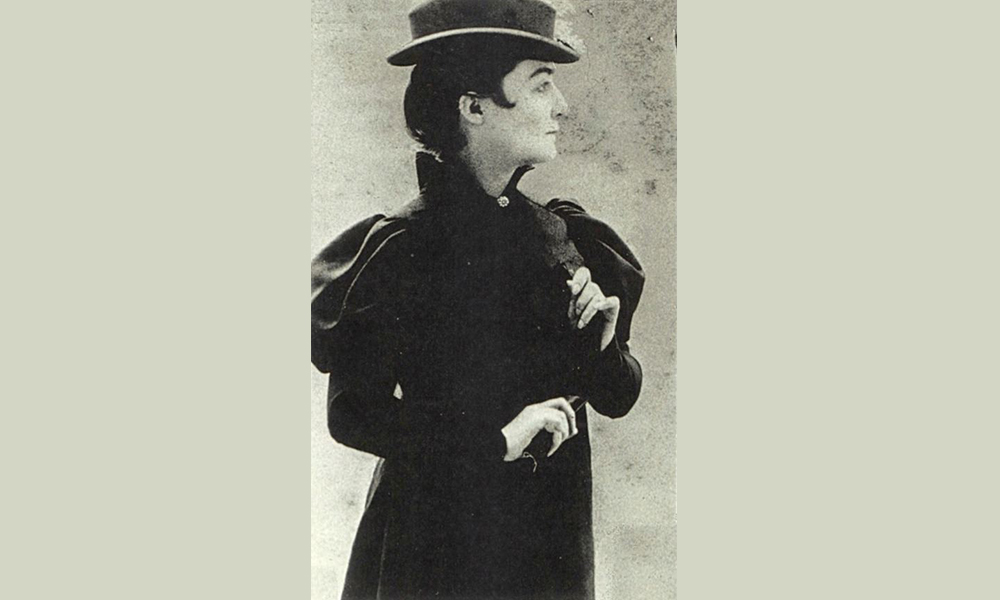

Around the same time, Marc de Montifaud dispensed of her own given name, Marie, as soon as she started writing. For both authors, these were not so much pseudonyms as new identities by which they would be known for the rest of their lives. Both cropped their hair short and sported men’s clothing. Rachilde circulated with a calling card that read “man of letters”; for a time, she insisted on being called “mon camarade.” Montifaud received letters in the feminine and the masculine; often the gender on the envelope did not match the gender on what was inside. Writing, for both, was the way to live out a gender that matched their internal self.

But what was that gender, exactly? It’s easy enough to recognize that these gender non-conforming writers did not fit into traditional categories of femininity. “I am not a woman” is a statement that Rachilde made throughout her life. But like her frustrated suitor, those around could not understand. They thought she was being playful, or rebellious. They could not understand that she was trying to speak through a body that had no apparent language.

Up until very recently, there was no obvious way to speak about gender non-conformity in a binary language like English or French. But that doesn’t mean people haven’t been trying for some time. What’s more, historical examples of what we now describe as trans identities are not limited to those who identified with or passed as the opposite sex. Rachilde pushed against the limits of gendered language by imagining women who became cats, women who went mad, women who dressed as men, and women who loved as men. She wasn’t quite sure what she was: a monster, a hysteric, or a werewolf. But she was certain that the word woman did not describe her.

Montifaud expressed her gender through a searing rage that runs through her writings, many of which were censored for pornography. She was outraged that her infractions earned her sentencing to a women’s prison rather than the prison where boundary-crossing male writers were sent. Most of all, she was furious at being misunderstood. “I am me,” she offered, wondering why that was not enough, in the absence of a vocabulary, or any other point of reference through which to clarify.

In the midst of our so-called “transgender tipping point,” the pronoun “they” makes visible an identity that we now recognize as multivalent, variable, and different for each individual: people can be “they” in as many ways as they can be “she” or “he.” It is tempting to take the new language of trans that has emerged in recent years and apply it backwards: to refer to Rachilde and Montifaud as “they.” Perhaps that would have pleased them. But the new vocabulary is ours, not theirs, marking the difference between 1884 and 2019. In the 1880s, there was no pronoun to do this work of self-declaration. Instead, these individuals had to work to carve out a space for themselves in every story they told. As writers they were lucky, with the will and the imagination to force their way into existence through linguistic manipulations and literary ingenuity. In this way, Rachilde fought off her suicidal thoughts; Montifaud released her anger.

But what of the countless others in history who were forced to live in a language that did not fit, with no reference point, no categories through which to understand that they were not alone in their difference? Montifaud wrote a biography of the Abbé de Choisy, the 17th-century nobleman who lived part of his life as a woman. Rachilde once described herself as a female Chevalier d’Eon, the illustrious 18th-century knight who lived 49 years as a man, and the other 30 as a woman. Gender non-conformity, they both realized, was nothing new, and its forms were often disparate. In other words, they is hardly a sign that we have pushed our language too far. Rather, it is a sign that language has finally managed to catch up with us.

Rachel Mesch teaches French literature, history, and culture at Yeshiva University in New York. She is the author of the forthcoming book Before Trans: Three Gender Stories from Nineteenth-Century France.