Bill Gass landed on me in Salt Lake City in 1983. I’d been running away from a lot of things, the most recent a jail gang in Davis, California (believe me, I was innocent). Francois Camoin, the lead fiction writer at the U of U was bringing Gass in for a reading and arranged for a handful of fiction writers to send Gass some of their stuff. I didn’t. Not at first. But the poet I was seeing there, Gail Wronsky (still my life partner now), said, “You nut, it’s William H. Gass!” So I sent him the beginning of my second Loop novel. Was the first published? No, not yet. Of Gass I’d only read On Being Blue.

Camoin was crazy for Gass. While waiting for Gass’s visit he had me read Omensetter’s Luck and Fiction and the Figures of Life. My head was turned. Gass was a nihilist and a nominalist, just like me! Though my propensities stemmed from the Nothingness School of Buddhism. Anyway, I didn’t expect Gass to like my work. He was famous. I didn’t even expect him to read it.

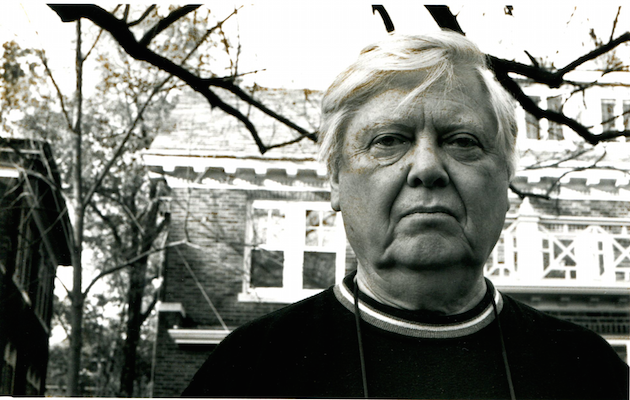

So the story goes that Gass got to Salt Lake and said, “Where’s Rosenthal?” Did he want to kill me? He had a reputation then, as he did till the end, of being cranky, negative, and irascible, if poignant. Dutifully, I went to my scheduled appointment with William H. Gass. He sat behind a desk, round faced, floppy white hair, an open collared shirt. His eyes, who ever talks about his eyes? Are the eyes a window to something? In this case, yes. His eyes, blue and silver, sparkled with intensity, both authoritative and curious. He held up my pages after we said hello. He looked at me and said, “You’re the real thing.”

He went on to say that it didn’t mean much. More likely it would lead to my being ignored, misunderstood, at best criticized. But he’d tell his publisher to read my work. There’s a long and a short here, but the short was that I got my first novel published. Bill blurbed it. He didn’t do that for many people. The rest is my long and unnoticeable career and, with Bill Gass, a long friendship.

So we stayed in touch. I read his other work. I wrote him letters about it. He wrote back. We were both funny. We had some odd things in common. His degree from Cornell was in philosophy. I had philosophy degrees, though he liked Aristotle and I like Plato. We both liked Godzilla movies, Gertrude Stein, Flaubert, Lowry. Once, at dinner at their place in University City, St. Louis, we got on favorite movies. I said mine were Woman in the Dunes and Zulu.

“Yes,” said Bill, “Zulu!”

“Oh no. Not possible,” said Mary Gass.

“If you want to understand men,” Bill said, “you must understand Zulu.”

Mary hid her face in her hands. “I don’t want to know,” she said.

Over time, as I published, I sent him copies of my books. He sent me copies of his. Unsigned. He didn’t like signing books so much.

I got a degree in Utah, published my novel, got a teaching job; so did Gail. We moved to LA, first Venice Beach, then Topanga Canyon. We had lunch with Bill and his wife, Mary, when they came to town, at our home in Topanga, or in Santa Monica (we always shared a bottle of wine, or two) though the visit I remember distinctly was just after the huge Old Canyon Fire. After lunch at our place, Bill wanted to see some burn area. We drove to Red Rock Canyon and walked amidst the tortured landscape. The ash from the blaze had turned silvery white and lay on the twisted, black skeletons of the oaks like snow. Bill was a dedicated photographer and a good one. We spent some hours there, Bill taking close-up photos of the burned trees, and Mary taking pictures of Bill taking pictures. I liked to watch him walk. He walked with his whole body in a kind of floppy loll. There was casual celebration to his walking.

On the way back to our place I asked him where he was staying and he said The Ritz in the Marina, the 22nd floor.

“Better hope we don’t have an earthquake,” I said. “The Marina is built on sand like Mexico City.”

Early the next morning the Northridge Quake hit. I called him the minute we stopped shaking.

“You’re alive,” I said.

“It doesn’t feel like it,” he said. “What should we do?”

“Take the stairs to the first floor. Should I come get you?”

“No, we’ll be all right. I have to prepare for the panel tonight.”

And the panel went on as scheduled at the Pacific Design Center. He read briefly with William Gaddis, then they talked. Gaddis spread rancor like machine gun fire. He ridiculed his daughter, who sat in the front row, as a failed artist. He went after Gass as a spineless nominalist.

“I’ve been over that with you already,” said Bill Gass, “and I’m not going to do it again.”

Gass remained loyal to Gaddis to the end, because “he was a magnificent writer.”

During his Getty Fellowship we met a number of times for lunch or dinner. Once we had dinner at his Getty apartment with Bill, Mary, and Michael Silverblatt. While talking about Gertrude Stein, Silverblatt got up and lay down on the floor between us, staring at the ceiling. Nobody said a word about it. We just kept talking and after awhile Michael got up and sat down again.

Later Gass asked me, “Does he do that often?”

“I don’t know,” I said. “I don’t have dinner with him.”

Sometimes we talked about writers and writing. He didn’t like Realism or Iowa Minimalism.

“Carver?” I said.

“Some people say he ruined American writing,” said Gass, “but it was happening anyway. A plot is where you bury someone. I don’t teach workshops. I teach philosophy.”

“Workshops teach you how to build a fortress,” I said.

“Yes, unassailable writing,” he said, “and boring. Iowa is a place to play golf. To write like an endless cornfield in the wicked present tense. You can tell good writing in the first paragraph. I did with you.”

Later in the stay we took him and Mary out to dinner in Beverly Hills at the Tribeca. It was crowded and noisy and we had to raise our voices to converse. Usually Bill ordered wine, but if the place had a bar he joined me for a martini. Some years later, when he wasn’t drinking hard liquor anymore, he still shared a martini with me before dinner or cognac before bed. Then Mary would look at us like she was watching Zulu. That night, Rod Stewart burst into the dining area followed by a bevy of sexy young women. When it came time to order Gass pointed at Stewart and said “I’ll have whatever he’s having.” And he did.

In 2002, my daughter, Marlena, then thirteen, and I drove across the country, taking only back roads. We followed the Mississippi River from New Orleans, eventually arriving in St. Louis. Bill opened wine when we arrived. In fact, Bill and Mary opened a bottle of wine at 5 p.m. everyday, at least when I was with them. They stopped whatever work they might be doing and drank wine.

Bill and Mary Gass were gracious hosts, Mary a good cook, though often we went out. Bill drank. He was unabashed. Mary pushed him to drink more water. His water sat in front of him. “I’ve never done a healthy thing in my life,” he said. He raised his wine glass to the air. “To genetics.” Afternoons, Mary talked and swam with Marlena at their pool or went shopping. Bill and I talked: books, philosophy, consciousness, Descartes, Flaubert, through the afternoon, after dinner, into the night.

That night we sat across from each other on the living room floor on either side of a coffee table. I teased him about being a Romantic writer.

“Metafiction is not Romantic,” said Gass.

“On the Road was published the same year as In the Heart of the Heart of the Country,” I said. “Romantic titles?”

“That wasn’t my crowd. I didn’t run with them.”

“Burroughs?”

Gass just tilted his head.

Mary descended from upstairs where she read or worked on her most recent architecture project.

“You two have to break it up,” she said.

“I don’t ever get to do this,” he said, though I doubted it.

I told him that night that I’d bought the CD of The Tunnel he’d recorded for Dalkey Archive. It arrived blank. I thought he’d find it funny, but he didn’t.

“Life is meaningless,” he said. But he poured another round of cognac and said, “Let’s have another before Mary comes for me again.”

And eventually Mary did try to roust him again, and then again, before dragging him off.

Their home was an amazing mansion with a wide marble staircase leading up to the second floor, one bedroom to the right, the master bedroom to the left. He said they bought for a song, as did his neighbors their homes. Now no one could afford to heat them. Downstairs a huge dining table sat off the kitchen. There was a kitchen nook, too, where you could look out to the yard and a flowering garden. There was a huge, comfortable living room. The rest of the second floor was rooms full of book shelves, as was the third floor and the basement. Stack upon stack of books; more books than a small library. You didn’t walk through those spaces, you wended. He loved photography and he had it up on his walls. His close friend and neighbor across the street was the photographer, Michael Eastman, who had just published a book of black and white photographs of horses. The photos were innovative and gorgeous. Gass had written the preface. He had some of those photos on his walls now.

He knew I owned a horse and when he showed me the book he apologized for the preface. “You know much more about horses,” he said. “You and Hawkes, but you’ll like the photographs.” Later, when I published my second horse book, Eastman gave me the photo for my cover.

During that visit Bill brought Marlena and me to a wooden secretary on the first floor to show us something. He opened the top drawer where a dozen small, intricate objects spread out. “Models of the universe,” he said. “I collect them.”

They were very abstract. A structure around a non-working gyroscope, a set of clear nesting dolls, a sculpture made of typewriter keys, a small automatic cat feeder that couldn’t feed a mouse.

He picked one up. “Want to hold one?”

I put out my hand. The thing was intricate, made of paper and wood; it looked like a miniature Frank Stella sculpture.

“A universe. You can throw it, kiss it, crush it in your hand,” said Bill. Quintessential Gass.

Earlier in the year I’d published a book about a philosophical female dragon who terrorizes the world.

Gass blurbed the novel, Godzilla at his side.

Mary took a photo of Bill, Marlena, and me in their yard before we left. I have it hanging in my writing office. I’m grinning like a happy fool. Bill looks like he’s trying to pretend he’s enjoying it. He looks too serious, too much like the man who produced so much acerbic, if witty, cynicism about literature and the world. He didn’t really like having his picture taken so much.

When we left the next day to head for my hometown, Marlena turned to me as we waved goodbye. “That’s the smartest man in the world,” she said.

Our last encounter came about a half-decade ago when a couple of young film makers decided to make a movie about American literary authors. They knew I knew Bill and asked if they could film us. I called Bill and asked him if he was interested.

“I’ll ask Mary,” he said.

I gave him their names and Mary looked them up on the internet.

“I found them,” she said. “It’s okay.”

So the three of us flew to St. Louis, cameras and microphones at my back. When we arrived at Bill’s front door he hugged me and said, “How wonderful to see you. Have you written anything good yet?” Of course we had to re-shoot that several times.

We spent three days shooting, in his office, his living room, talking as we walked down his street, breaking at five for wine. We talked about our work. I talked about his influence. I said he was my literary and intellectual father. They made him talk about me.

I was embarrassed. He took the filmmakers to the basement where he kept the copies of the books I’d sent him. Okay, Gass’s basement. I’ll take it. In the end, like most Hollywood projects, the film was never made.

In time our correspondence “degenerated,” as he put it, to emails: his bad heart. Mary’s illness, my cancer, how reviewers misread his books. We stayed in touch. But in the last couple of years, he stopped getting back to me. That, I figured, was his prerogative. But fearing the worst I recently planned to write him and Mary a letter. He died before I wrote it.

Bill Gass was extremely gracious. He was funny. He was jovial. He and Mary’s love for each other was symbiotic and effusive. I loved him and I grieve for him. I’m thinking about starting my own collection of models of the universe. Maybe I’ll start with the blank CD of The Tunnel.