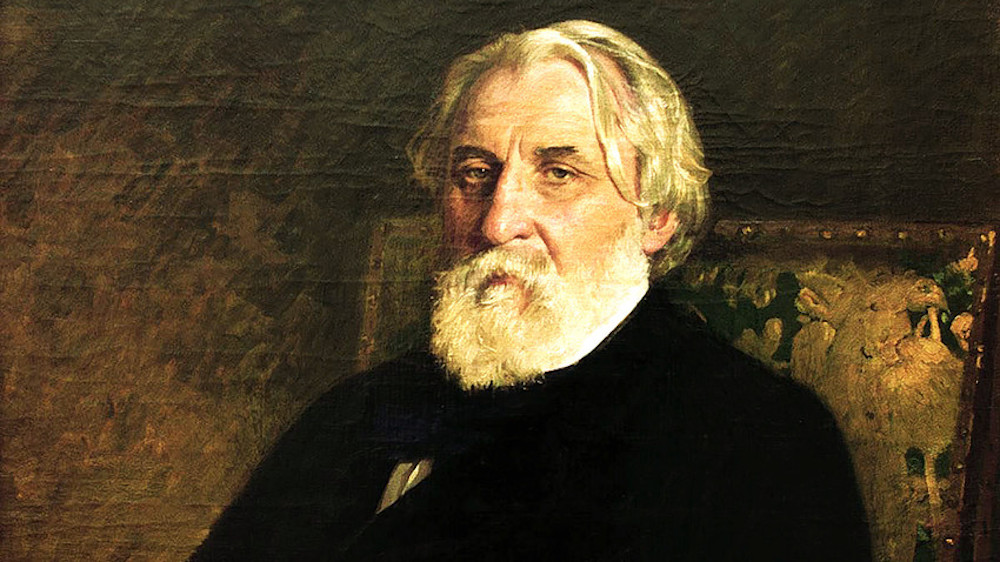

Ivan Sergeyevich Turgenev is probably the most European of the great 19th-century Russian novelists. He was born 200 years ago, on November 9, 1818, on his mother’s vast estate in Oryol, some 300 miles southwest of Moscow. His father was a handsome young cavalry officer who had arrived quite by chance at the estate, which appears to have been a self-contained kingdom with a private orchestra — and five thousand serfs.

The unsuspecting officer, himself an impoverished member of a once great family tracing its origins back to the 15th century, had been scouting horses for his regiment. Instead of finding additional mounts, the future writer’s father married the charmless heiress, six years his senior and lacking any obvious suitor. There were reasons: Turgenev’s mother was a feudal tyrant who beat her children with much the same abandon she applied when disciplining her serfs. Even so, his country childhood left Turgenev with an abiding love of nature. This was matched by an avowed hatred of serfdom, which his writings would eventually help abolish. He was fond of his weak, socially-misplaced father, who, aware that Russian aristocrats favored French for conversation and correspondence, urged his children to practice writing in Russian at least twice a week and, most particularly, when writing to him.

In the interests of the young Turgenev’s further education, the family moved to Moscow when he was nine. Already fluent in German, English, and French — thanks to a succession of foreign governesses — as well as Russian, he entered university in St. Petersburg at 16 to read philosophy. Within three years, his first poems were published. It was then that Turgenev made the move that not only set him apart from his peers, but which would also shape his fiction.

Intent on further study, he went to Berlin, where he absorbed German idealism and the writings of Goethe; he would continue to visit Germany, particularly Baden-Baden, throughout his life. Not surprisingly, Turgenev’s fiction often features disaffected, foreign-educated intellectuals. After two years in Berlin, he returned to Russia and completed a master’s degree in philosophy at the University of Moscow. Tall, attractive, languid, and surprisingly soft-spoken, Turgenev first achieved fame with his realist stories, Notes of a Hunter (first translated as A Sportsman’s Sketches), which were serialized between 1847 and 1851 and afterwards collected in a handsome single volume.

Eleven years earlier, in 1843, while out hunting on his 25th birthday, he met a middle-aged man, and, a few days later, was presented to his new acquaintance’s wife. Pauline Viardot was a famous — and reportedly plain — Paris-born opera singer of Spanish descent. He fell in love; Viardot and her husband appeared to accept this devotion. Turgenev and Viardot may or may not have been lovers, but they shared an intense bond. He learnt Spanish, resigned his post at the Ministry of the Interior, and travelled through Europe as part of her entourage. He sent his daughter, whom he had had with a seamstress, one of his mother’s peasants, to Paris, to be raised with Viardot’s children.

Close friends with Flaubert, Turgenev, who never married, became a familiar figure in the literary circles of France, where he died on September 3, 1883, near Paris, after a year battling spinal cancer. He was 64. His love of Russia had endured and his body was sent to St Petersburg for burial in the Volkovo cemetery, a non-Orthodox public graveyard.

How did the restless man about town, famous for his sketches and his extensive travels, turn to fiction? An obituary he wrote on the death of Nikolai Gogol in 1852, the same year that saw the publication of his collected Notes of a Hunter, proved so contentious that it was banned and resulted in Turgenev being exiled for two years to his estate of Spasskoye-Lutovinovo. There he wrote four extraordinary novels — Rudin, Home of the Gentry, On the Eve, and Fathers and Sons — as well as the novella First Love.

In Rudin, published in 1856, the eponymous hero personifies the new Russian consciousness, the desire to take action and liberalize a country crippled by conservatism. Full of long, dramatic conversations, the novel reads as a theater piece. By then, Turgenev had already written A Month in the Country, his only full-length work for the stage. Years ahead of its time, with its clever use of comic farce in exposing of human foibles, it had been banned in Russia, undermining Turgenev’s confidence in his dramatic talents. At long last produced in 1872, A Month in the Country pre-empts Anton Chekhov’s plays and would, in tandem with Chekhov, revolutionize Russian theater.

Home of the Gentry was completed on the eve of Turgenev’s 40th birthday. In this mid-life novel of a homecoming, the central character, Lavretsky, seeks comfort in his country estate after his marriage collapses. Not the most sophisticated of individuals, he has been betrayed by his wife, the first woman he had ever encountered, and is deeply wounded. In his despair, he finds himself by chance being drawn to Liza, the quiet, deeply religious daughter of a highly irritating female relative. The situation is complicated by the interaction of a brilliantly drawn set of characters. Social observation came naturally to Turgenev, and it is interesting to compare him with Jane Austen, who died the year before he was born. Home of the Gentry is personal, but it also looks to the wider experiences of a generation of Russians who had sampled the West, only to return home. Turgenev, a cosmopolitan revolutionary as well as a conservative traditionalist, studied both the old and new faces of his motherland. Home of the Gentry reveals Turgenev at his sharpest, yet for all the caustic observation it is an elegiac variation of a conflict that would also dominate his masterwork, Fathers and Sons.That novel introduces the complex presence of Bazarov, the “nihilist,” one of world literature’s most enduring creations. Self-assured and relentless, Bazarov represents a Russia even more bent on change than it was in the time of Rudin.

Published in 1861 to a poor critical response in Russia, the emotionally ambivalent Fathers and Sons is among the towering achievements of the 19th-century Russian novel and of world literature as a whole. It explores the distinctions between friendship and affection, passion and mere sexual curiosity, as well as the limits of loyalty, the power of a father’s love for his son, and, most of all, the tension between the values and traditions of old Russia and a new world order about to announce itself in a bloody revolution.

Written in between Home of the Gentry, Fathers and Sons, and Turgenev’s third novel, On the Eve (1859), a near operatic tale featuring Elena, a self-sacrificing, fearless heroine — is the exquisite novella First Love, in which a man is asked over supper to recount his earliest romance. He agrees, but insists on first writing it all down. In the narrative, he recalls how his younger self idealized a slightly older girl only to find a rival in none other than his unhappy father. A work of devastating beauty, First Love pits a boy’s infatuation against an older man’s tormented passion. Turgenev is known to have drawn upon memories of his own dead father, who had married for money, to his shame and regret.

An instinctive stylist who created his characters by infiltrating their psyches and, crucially, examining their behavior, Turgenev, whose interest in Western European culture outraged Dostoyevsky, would become an inspiration for Henry James, who referred to Turgenev as “the beautiful genius.” Turgenev’s influence on Chekhov is obvious; more intriguingly, one feels his presence in the work of the Irish playwright Brian Friel and the Irish novelist and master of the short story William Trevor. And if one were asked to nominate a work that immediately suggests the Russian master, a reflex reaction may well be to suggest The Great Gatsby. Nick Carraway could easily be a character created by Turgenev.

He remains revered — an artist capable of dissecting human emotions with a delicate, candid brutality. For Ivan Turgenev, the artist can only hope to teach “by giving the world images of beauty,” which he did in melancholic narratives which achieve the profundity of a Beethoven piano sonata.