At the time of this writing, the Malibu fires are at 20% containment. I live in West Los Angeles. The air smells like smoke. I keep fighting an irritation in my throat — like a fleck of debris I can’t swallow. The name of the fire is the Woolsey Fire — I don’t know why. But “Woolsey” feels apt, somehow, like the name of a beloved stuffed toy in a children’s book, bound for incineration.

I lived in New York for a decade. When I pined for Los Angeles, my hometown, I’d go on a mental drive north on the PCH: the glittering water on my left, the cliffs on my right. As a child, gazing at the surf and surrounding bluffs, I’d marvel at their changelessness: “What I see now is what someone saw one hundred years ago,” I’d think. “One thousand years ago…” And so on. I’d imagine myself as a 1950’s movie star, Marilyn Monroe in her white one-piece, or a mustachioed conquistador. Sometimes, I was a Chumash Native, cracking mussels open on the rocks, or — most inconceivable and exciting of all — my parents when they were young. Sometimes, I imagined myself in some distant, unforeseeable future, civilization as I knew it long crumbled and swept away, and me — the view’s sole witness — the feral girl-child who, through sheer grit and ingenuity, survived. I so thoroughly inhabited the gazes of these imagined people I sometimes found myself seized by a physical thrill — a sudden, prickling shiver — which I half-believed was my spirit, returning to my body from its journey through time and space.

Now, as images of the devastation in Malibu begin to roll in — a singed, lonely owl huddled on the beach, recycling bins puddled like wax, palm trees and hillsides and mansions ablaze — I feel a version of that same shiver. Here is the dystopian future I imagined as a child — a future I never imagined I’d see. (In my fantasies, the end of civilization had always already occurred decades, if not centuries, before, for reasons undetermined.) The sun is a neon disc behind a haze of ash — it’s otherworldly — and I find myself fighting a familiar sadness, a dull grief I’ve battled off and on for the past two years. That these fires erupted on November 9th — two years to the day after Trump officially won the presidency — is not lost on me.

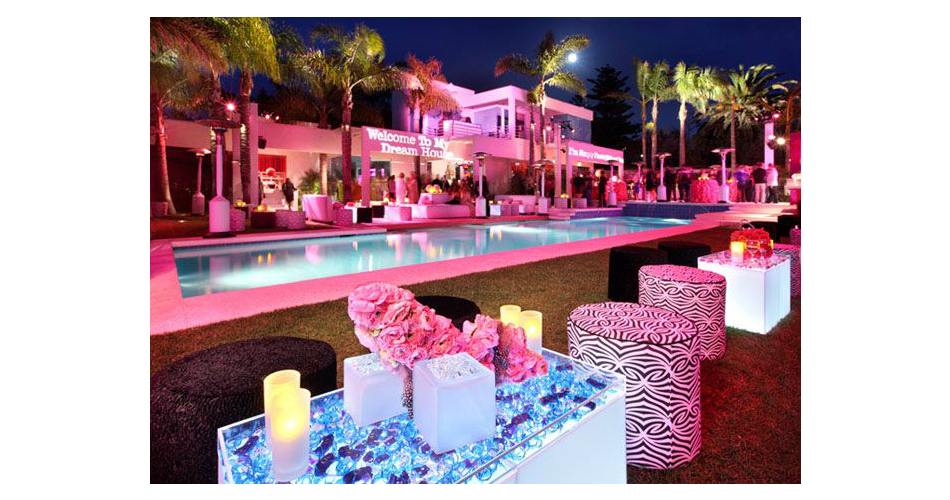

Like that election, the burning of Malibu feels like the loss of America itself, the end of the so-called “civilized Western world.” Because what is Malibu if not America’s Valhalla — the magnificent palace lying in wait for those who sacrifice their lives to the noble cause of capitalism — who work, sacrifice, scrimp, and save their way to paradise? Multiple generations of girls (myself included) were all but indoctrinated to associate Malibu with happiness: “Malibu Barbie,” she of voluminous blonde hair, aqua-blue eyes, tanned limbs, and something Barbie manufacturers christened, “Stacey face,” embodied all to which we were supposed to aspire. She drove a Malibu pink convertible and lived in a Malibu dream house. She didn’t work to become who she was — she was born that way. Malibu Barbie was white privilege personified.

Of course, most children only ever play at this life. As adults, many turn into dolls themselves — people who are not quite “real” in the world in which they live, their lives utterly dictated by those who own or “employ” them. They are powerless. But — with their Malibu Barbies and, later, their “American Dream” — they can pretend.

So, what happens, then, when the dream house goes up in flames?

Perhaps it’s this collision — between childhood fantasy and real-life horror — that feels so significant and irrevocable. We know these wildfires—the largest and most destructive in the history of the state — are the product of climate change. In my relatively short time on the planet, I’ve witnessed a dramatic altering in the weather here — the bizarre, East Coast-like humidity during the summer, the negligible rainfall year-round, the premature budding of leaves, and, of course, the fires.

Months ago, I went on a hike in Temescal Canyon — a trail in the hills just south of Topanga, where my father grew up — and a little girl with whom I crossed paths asked, “how long until the waterfall?” I told her about 15 minutes. But I haven’t seen the waterfall in years. The rickety wood bridge is still there, but the stream is dried up, reduced to a collection of rocks. Sometimes, when it rains, a feeble trickle appears — enough to attract mosquitoes, to paint a few stones with moss. But I remember playing there with my brother when we were kids — squatting on boulders to peer down at tadpoles, sending twigs on dizzy journeys downstream. We didn’t have to ask, “how long until the waterfall?” We knew that when we got close, we’d hear it.

I have always loved Malibu. Its strange mix of untenable wealth and ramshackle beach culture spoke to me, embodied an important message. “You see this house?” Malibu says. “This beautiful, expansive house you can’t afford? The rows of windows glinting in the cliffs? The private roads winding past banana tree attended gates?”

I do.

“Now, look the other way,” Malibu goes on. “See the sunset — the cumulus heaps of glowing oranges and pinks, the slow chill of lavenders and deepening blues. Hear the ocean — the crashing waves, the skeletal rattle of water-dragged stones, the pounding surf, inexorable as a heartbeat. Watch the wheeling seagulls. Breathe the salted breeze. All of it is yours. No one can buy this. No one can own what matters.”

So, what are these Malibu wildfires, I wonder, if not a direct message to America — to Trump and all he represents — that wealth does not matter? That the world is changing at an alarming rate, and money cannot protect us? The old stories we tell ourselves about how best to live, they are dried up and gone. We need a new American Dream — a dream that values the environment over the dollar, humanity over consumption, and real life over dreams.

Barbie’s Malibu dream house is burning. The tiny pink furniture, the turrets, the balconies, the spiraling staircase — her Ivanka hair and tan plastic skin — all of it melted beyond recognition.

How is it the more we violate our world, the more sublime it becomes? The hurricanes, the calving glaciers, the mudslides, the fires and floods: every month, it seems, we are offered a new experience of the infinite, terrifying and awe-inducing, with the power to extinguish human existence, both literally and philosophically. It’s strange to fathom, but the most beautiful sunsets will come in the wake of our annihilation, with no human being around to witness them — our pollution hovering across the earth like a ghost.

At the time of publication, the Woolsey Fire is 40% contained. It’s been burning for 10 days.